Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

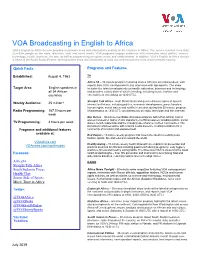

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

Perceptive Intent in the Works of Guenter Grass: an Investigation and Assessment with Extensive Bibliography

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Perceptive Intent in the Works of Guenter Grass: an Investigation and Assessment With Extensive Bibliography. George Alexander Everett rJ Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Everett, George Alexander Jr, "Perceptive Intent in the Works of Guenter Grass: an Investigation and Assessment With Extensive Bibliography." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1980. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1980 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 71-29,361 EVERETT, Jr., George Alexander, 1942- PRECEPTIVE INTENT IN THE WORKS OF GUNTER GRASS: AN INVESTIGATION AND ASSESSMENT WITH EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PRECEPTIVE INTENT IN THE WORKS OF GUNTER GRASS; AN INVESTIGATION AND ASSESSMENT WITH EXTENSIVE BIBIIOGRAPHY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Foreign Languages by George Alexander Everett, Jr. B.A., University of Mississippi, 1964 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1966 May, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Central Europe

Central Europe West Germany FOREIGN POLICY wTHEN CHANCELLOR Ludwig Erhard's coalition government sud- denly collapsed in October 1966, none of the Federal Republic's major for- eign policy goals, such as the reunification of Germany and the improvement of relations with its Eastern neighbors, with France, NATO, the Arab coun- tries, and with the new African nations had as yet been achieved. Relations with the United States What actually brought the political and economic crisis into the open and hastened Erhard's downfall was that he returned empty-handed from his Sep- tember visit to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Erhard appealed to Johnson for an extension of the date when payment of $3 billion was due for military equipment which West Germany had bought from the United States to bal- ance dollar expenses for keeping American troops in West Germany. (By the end of 1966, Germany paid DM2.9 billion of the total DM5.4 billion, provided in the agreements between the United States government and the Germans late in 1965. The remaining DM2.5 billion were to be paid in 1967.) During these talks Erhard also expressed his government's wish that American troops in West Germany remain at their present strength. Al- though Erhard's reception in Washington and Texas was friendly, he gained no major concessions. Late in October the United States and the United Kingdom began talks with the Federal Republic on major economic and military problems. Relations with France When Erhard visited France in February, President Charles de Gaulle gave reassurances that France would not recognize the East German regime, that he would advocate the cause of Germany in Moscow, and that he would 349 350 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1967 approve intensified political and cultural cooperation between the six Com- mon Market powers—France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. -

The Polish Phenomenon What’S Next for Europe’S New Powerhouse?

Report on the Kosciuszko Foundation Economic Conference 2013 The Polish Phenomenon What’s Next for Europe’s New Powerhouse? PRODUCED BY CONTENTS FOREWORD: Shedding Light on the Polish Phenomenon ........................... 1 PANEL ONE: Riding Out the Storm—How the Finance and Banking Sector in Poland Navigated the Recession and the Path Ahead ........................................................................................ 2 KEYNOTE SPEAKER: Marek Belka, President of the National Bank of Poland .................................................... 12 KEYNOTE PRESENTATION: The Polish Economy and the Global Financial Crisis—Strengths and Challenges ..................................... 13 PANEL TWO: The Land of Opportunity—an Investor Perspective .............. 20 THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION: The American Center of Polish Culture ........................................................ 30 FOREWORD Shedding Light on the Polish Phenomenon THERE’S AN OLD JOKE ABOUT HOW MANY POLES IT TOOK TO SCREW IN A LIGHT BULB. BUT AFTER A POLISH ELECTRICIAN NAMED LECH WALESA PULLED THE PLUG ON COMMUNISM AND HELPED BRING DOWN THE SOVIET UNION, THAT JOKE LOST ITS LUSTER. THESE DAYS THE LIGHT BULBS ARE MADE IN POLAND, AND OVER THE PAST TWO DECADES, THE COUNTRY’S ECONOMY HAS GROWN AT A RECORD PACE COMPARED TO ITS NEIGHBORS. September 2013 marked the 20th anniversary of Russia’s withdrawal of the Soviet army from Poland. Since then, Poland has gone from Communist basket case to what German magazine Der Spiegel dubbed last year as: “The Miracle Next Door: Poland Emerges as a Central European Powerhouse.” Poland is the only European Union economy to avoid recession since the global nancial crisis hit in 2008. Polish workers used to travel abroad to where the factories were. These days, factories move ALEX STOROZYNSKI to where the Polish workers are. -

The Roots and Consequences of Euroskepticism: an Evaluation of the United Kingdom Independence Party

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Political Science Publications Department of Political Science 4-2012 The roots and consequences of Euroskepticism: an evaluation of the United Kingdom Independence Party John B. Sutcliffe University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/poliscipub Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Sutcliffe, John B.. (2012). The roots and consequences of Euroskepticism: an evaluation of the United Kingdom Independence Party. Geopolitics, history and international relations, 4 (1), 107-127. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/poliscipub/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Science at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations Volume 4(1), 2012, pp. 107–127, ISSN 1948-9145 THE ROOTS AND CONSEQUENCES OF EUROSKEPTICISM: AN EVALUATION OF THE UNITED KINGDOM INDEPENDENCE PARTY JOHN B. SUTCLIFFE [email protected] University of Windsor ABSTRACT. This article examines the causes and consequences of Euroskepticism through a study of the United Kingdom Independence Party. Based on an analysis of UKIP’s election campaigns, policies and performance, the article examines the roots of UKIP and its, potential, consequences for the British political system. The article argues that UKIP provides an example of Euroskepticism as the “politics of oppo- sition.” The party remains at the fringes of the political system and its leadership is prepared to use misrepresentation and populist rhetoric in an attempt to secure sup- port. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

British Anti-Communist Propaganda and Cooperation with the United States, 1945-1951. Andrew Defty

British anti-communist propaganda and cooperation with the United States, 1945-1951. Andrew Defty European Studies Research Institute School of English, Sociology, Politics and Contemporary History University of Salford Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, January 2002 British anti-communist propaganda and cooperation with the United States, 1945-1951 Contents Acknowledgements................................................................................................. .......ii Abbreviations.................................................................................................................iii Abstract..........................................................................................................................iv Introduction....................................................................................................................! Chapter 1 The Origins of Britain's anti-communist propaganda policy 1945-1947.............................28 Chapter 2 Launching the new propaganda policy, 1948.....................................................................74 Chapter 3 Building a concerted counter-offensive: cooperation with other powers, 1948-1950 ........123 Chapter 4 'Close and continuous liaison': British and American cooperation, 1950-1951 .................162 Conclusion .....................................................................................................................216 Notes Introduction .........................................................................................................226 -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Pr Never Judge a Book by Its Cover

NEVER JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER Effearte is pleased to present the next group show “Never Judge A Book By Its Cover”. 13 artists will explore the illustration and publishing industry throughout cover books. Lately everybody talks about it. Adelphi organized a cover contest on its Facebook page, Garzanti asked his readers to choose the cover of the next upcoming book publishing, La Stampa and Il Sole 24 Ore dedicated a column to this subject. A book cover is essential. It is its garment and tells us everything about it. Very often we choose a book for its look and sometimes we don’t buy it because it doesn’t attract us. In the last decade the world of book covers, which is in constant evolution, pushed itself on themes that would have been totally unthinkable before. This is thanks to wishful thinkers art directors, brave editors and, at least but not last, the tremendous contribution of certain artists who offered their art to the editorial world. Among others, very relevant was proved to be the restyling process carried out by some of the most important publishing houses of famous authors such as Einaudi with Murakami or Feltrinelli with Bukowski and Miller. This process ended up being the result of a synthesis between aesthetic and significance. All the works are illustrations of book covers. Never Judge a Book By Its Cover is a panning shot of the most significant Italian (and not only) illustrators who provide their talent and their art to the publishing world, leaving an important and distinguishable sign. -

The Authorised History of MI5 by Christopher Andrew (Book Review)

Lobster 58 The Defence of the Realm The Authorised History of MI5 Christopher Andrew Page 134 Winter 2009/10 Lobster 58 London: Allen Lane, 2009, £30 Covering the same area as the Hennessy/Thomas book but with access to more recent MI5 documents, Andrew does at least refer to the dissenters named in the preceding paragraph. This is a thousand pages long and will be of major interest to academic students of British intelligence and political history for years to come. Discounted from sellers like Amazon, this is a seriously good buy. But I’m not an academic and my interests are political. I looked initially at two areas: what it said about MI5’s relationship with the British left since WW2, and particularly the role of the CPGB in British politics; and the so-called Wilson plots. Let’s take the left first. Elsewhere in this issue is my contribution to the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom’s book on the 1984 miners’ strike. In that I repeat for the umpteenth time Peter Wright’s story in Spycatcher that MI5 knew about the covert Soviet funding of the CPGB in the 1950s and neither exposed it nor tried to stop it. Wright is rubbished repeatedly by Andrew and he does not refer to this claim of Wright’s. However on p. 403 he writes this: ‘The Security Service had “good coverage” of the secret Soviet funding of the CPGB, monitoring by surveillance and telecheck the regular collection of Moscow’s cash subsidies by two members of the Party’s International Department, Eileen Palmer and Bob Stewart, from the north London address of two ex-trainees of the Moscow Radio School.’ This isn’t dated but from the context it is the early 1950s. -

Application/Pdf Checkout-Charlie Company

Welcome to Berlin, 23th of February 2021 News to categories click to INTERACTIVE DOCUMENT see website Use the interactive buttons to navigate through the presentation. You can find them in the index, too. back to index Content ABOUT US NEWS PORTALS 04 Checkout Charlie 10 A lot has happened 19 Incredible diversity WELCOME PACKAGES CONTENT OFFERS MULTIMEDIA OFFER 33 Your start with us 39 Content & campaigns 51 Visual and auditory EXPERTS CONTACT PERSON APPENDIX 55 For your appearance 57 Individual support 61 Newsletter, Incentive & more 04 About us From a bargain blog to a respected partner for content & discount campaigns, it has been an exciting path for us. And Checkout Charlie continues to develop further. We are pleased that you continue to accompany us as a partner on this exciting journey. ▪ Timeline ▪ Our markets ▪ The Checkout Charlie universe ▪ Facts About us News Portals Welcome Content Multimedia Experts Contact Once upon a time — from a blog to an all-rounder For more than 12 years, we have been making the world Sparwelt.de started as a bargain shopping blog of online shopping a little bit better every day. And in 2008 doing so we focus just as much on our users as on our SPARWELT goes content partners. – with editorial content enjoyed by more than 2012 That‘s why our motto, “Shop better. Feel better.”, is our 1 million users/month greatest credo. SPARWELT joins the Media Group RTL We have been constantly developing our portal and 2014 Germany network, as well as our offers and services, from the Our first TV spot very start — driven by our own motivation to fulfil the campaign generates needs of users and retailers. -

'L'europe Oui, Maastricht Non' from Der Spiegel (14 September 1992)

'L'Europe oui, Maastricht non' from Der Spiegel (14 September 1992) Source: Der Spiegel. Das Deutsche Nachrichten-Magazin. Hrsg. AUGSTEIN, Rudolf ; Herausgeber DR. KADEN, Wolfgang; KILZ, Hans Werner. 14.09.1992, n° 38; 46. Jg. Hamburg: Spiegel Verlag Rudolf Augstein GmbH. "L'Europe oui, Maastricht non", auteur:Augstein, Rudolf , p. 168-169. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/l_europe_oui_maastricht_non_from_der_spiegel_14_septe mber_1992-en-51dee566-fbc0-4361-adb9-d4596f4ce11b.html Last updated: 06/07/2016 1/5 L’Europe oui, Maastricht non Rudolf Augstein If anyone wants to know why the battle over the Treaties of Maastricht has now degenerated into a round of scare mongering, they should take a look at what is currently happening in France. François Mitterrand speaks of a ‘battle that will be harder than I had expected’ when talking about the referendum that he himself has set for 20 September. His Prime Minister, Pierre Bérégovoy, is of the opinion that: A ‘no’ would lead to a division between France and Germany. The Germans would then regain their autonomy and, in future, look more to the East than to the West. The former Prime Minister, Michel Rocard, is quite blatant in immediately bringing up the heavy artillery: We must not make 20 September into another political Munich. He also feels obliged to protect Germany from ‘its demons’, while the Minister for Humanitarian Affairs, Bernard Kouchner, suggests that Helmut Kohl’s generation will be the last pro-European one in Germany, because it will be succeeded by the Rostock skinheads.