Social Innovation in an Era of Socio-Spatial Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESTE Foundation Project Space Slaughterhouse, Hydra Duration

Ίδρυµα ∆ΕΣΤΕ Εµ. Παππά & Φιλελλήνων 11. 142 34 Νέα Ιωνία ΑΘήνα Ελλάς DESTE Foundation 11 Filellinon & Em. Pappa St. 142 34 Nea Ionia Athens Greece WWW . DESTE . GR T — 30 210 27 58 490 F — 30 210 27 54 862 DESTE Foundation Project Space Slaughterhouse, Hydra Duration: June 21 – September 30, 2016 Opening Hours, Monday - Sunday: 11:00 - 13:00 & 19:00 – 22:00 Tuesday Closed — Project Coordinator: Marina Vranopoulou [email protected] — Media Contact: Regina Alivisatos [email protected] — Page 1 of 3 Ίδρυµα ∆ΕΣΤΕ “PUTIFERIO” Εµ. Παππά & Φιλελλήνων 11. A Project by Roberto Cuoghi 142 34 Νέα Ιωνία ΑΘήνα Ελλάς Candidates from the deep water DESTE Foundation Clashed with wasps they came to slaughter 11 Filellinon & Em. Pappa St. 142 34 Nea Ionia Pinching here, biting there, Athens Greece Oh my fellows please beware! WWW . DESTE . GR Smoke and flames, stink and froth, T — 30 210 27 58 490 F — 30 210 27 54 862 Splashing in a sulfurous broth Fished out at the seaside Unarmed, more dead than alive The candidates in the eventide Took your logic for a ride Internationally renowned Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi will be carrying out a major exhibition on the island of Hydra. Cuoghi was commissioned by the DESTE Foundation in the context of an exhibition program specially designed for the Foundation’s Project Space in the island’s former Slaughterhouse. Cuoghi’s exhibition is entitled “Putiferio”, in Latin "to bring the stink". “Putiferio” may also signify chaos or a small taste of hell. During the opening, the artist will transform the area around the Slaughterhouse into a camp to experiment archaic firing techniques for ceramic. -

Abai, Oracle of Apollo, 134 Achaia, 3Map; LH IIIC

INDEX Abai, oracle of Apollo, 134 Aghios Kosmas, 140 Achaia, 3map; LH IIIC pottery, 148; migration Aghios Minas (Drosia), 201 to northeast Aegean from, 188; nonpalatial Aghios Nikolaos (Vathy), 201 modes of political organization, 64n1, 112, Aghios Vasileios (Laconia), 3map, 9, 73n9, 243 120, 144; relations with Corinthian Gulf, 127; Agnanti, 158 “warrior burials”, 141. 144, 148, 188. See also agriculture, 18, 60, 207; access to resources, Ahhiyawa 61, 86, 88, 90, 101, 228; advent of iron Achaians, 110, 243 ploughshare, 171; Boeotia, 45–46; centralized Acharnai (Menidi), 55map, 66, 68map, 77map, consumption, 135; centralized production, 97–98, 104map, 238 73, 100, 113, 136; diffusion of, 245; East Lokris, Achinos, 197map, 203 49–50; Euboea, 52, 54, 209map; house-hold administration: absence of, 73, 141; as part of and community-based, 21, 135–36; intensified statehood, 66, 69, 71; center, 82; centralized, production, 70–71; large-scale (project), 121, 134, 238; complex offices for, 234; foreign, 64, 135; Lelantine Plain, 85, 207, 208–10; 107; Linear A, 9; Linear B, 9, 75–78, 84, nearest-neighbor analysis, 57; networks 94, 117–18; palatial, 27, 65, 69, 73–74, 105, of production, 101, 121; palatial control, 114; political, 63–64, 234–35; religious, 217; 10, 65, 69–70, 75, 81–83, 97, 207; Phokis, systems, 110, 113, 240; writing as technology 47; prehistoric Iron Age, 204–5, 242; for, 216–17 redistribution of products, 81, 101–2, 113, 135; Aegina, 9, 55map, 67, 99–100, 179, 219map subsistence, 73, 128, 190, 239; Thessaly 51, 70, Aeolians, 180, 187, 188 94–95; Thriasian Plain, 98 “age of heroes”, 151, 187, 200, 213, 222, 243, 260 agropastoral societies, 21, 26, 60, 84, 170 aggrandizement: competitive, 134; of the sea, 129; Ahhiyawa, 108–11 self-, 65, 66, 105, 147, 251 Aigai, 82 Aghia Elousa, 201 Aigaleo, Mt., 54, 55map, 96 Aghia Irini (Kea), 139map, 156, 197map, 199 Aigeira, 3map, 141 Aghia Marina Pyrgos, 77map, 81, 247 Akkadian, 105, 109, 255 Aghios Ilias, 85. -

Visa & Residence Permit Guide for Students

Ministry of Interior & Administrative Reconstruction Ministry of Foreign Affairs Directorate General for Citizenship & C GEN. DIRECTORATE FOR EUROPEAN AFFAIRS Immigration Policy C4 Directorate Justice, Home Affairs & Directorate for Immigration Policy Schengen Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.ypes.gr www.mfa.gr Visa & Residence Permit guide for students Index 1. EU/EEA Nationals 2. Non EU/EEA Nationals 2.a Mobility of Non EU/EEA Students - Moving between EU countries during my short-term visit – less than three months - Moving between EU countries during my long-term stay – more than three months 2.b Short courses in Greek Universities, not exceeding three months. 2.c Admission for studies in Greek Universities or for participation in exchange programs, under bilateral agreements or in projects funded by the European Union i.e “ERASMUS + (placement)” program for long-term stay (more than three months). - Studies in Greek universities (undergraduate, master and doctoral level - Participation in exchange programs, under interstate agreements, in cooperation projects funded by the European Union including «ERASMUS+ placement program» 3. Refusal of a National Visa (type D)/Rights of the applicant. 4. Right to appeal against the decision of the Consular Authority 5. Annex I - Application form for National Visa (sample) Annex II - Application form for Residence Permit Annex III - Refusal Form Annex IV - Photo specifications for a national visa application Annex V - Aliens and Immigration Departments Contacts 1 1. Students EU/EEA Nationals You will not require a visa for studies to enter Greece if you possess a valid passport from an EU Member State, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway or Switzerland. -

Copyright© 2017 M. Diakakis, G. Deligiannakis, K. Katsetsiadou, E. Lekkas, M. Melaki, Z. Antoniadis

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece Vol. 50, 2016 MAPPING AND CLASSIFICATION OF DIRECT EFFECTS OF THE FLOOD OF OCTOBER 2014 IN ATHENS Diakakis M. National & Kapodistrian University of Athens Deligiannakis G. Agricultural University of Athens Katsetsiadou K. National & Kapodistrian University of Athens Lekkas E. National & Kapodistrian University of Athens Melaki M. National & Kapodistrian University of Athens Antoniadis Z. National & Kapodistrian University of Athens http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11774 Copyright © 2017 M. Diakakis, G. Deligiannakis, K. Katsetsiadou, E. Lekkas, M. Melaki, Z. Antoniadis To cite this article: Diakakis, M., Deligiannakis, G., Katsetsiadou, K., Lekkas, E., Melaki, M., & Antoniadis, Z. (2016). MAPPING AND CLASSIFICATION OF DIRECT EFFECTS OF THE FLOOD OF OCTOBER 2014 IN ATHENS. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 50(2), 681-690. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11774 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 04/08/2019 09:23:57 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 04/08/2019 09:23:57 | Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, τόμος L, σελ. 681-690 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, vol. L, p. Πρακτικά 14ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Θεσσαλονίκη, Μάιος 2016 Proceedings of the 14th International Congress, Thessaloniki, May 2016 MAPPING AND CLASSIFICATION OF DIRECT EFFECTS OF THE FLOOD OF OCTOBER 2014 IN ATHENS Diakakis M.1, Deligiannakis G.2, Katsetsiadou K.1, Lekkas E.1, Melaki M.1 and Antoniadis Z.1 1National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Zografou, Athens, Greece, 302107274669, [email protected] 2Agricultural University of Athens, Athens, Greece, [email protected] Abstract In 24 October 2014, a high intensity storm hit Athens’ western suburbs causing extensive flash flooding phenomena. -

21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION Tel.: 2103202049, Fax: 2103226371

LIST OF BANK BRANCHES (BY HEBIC) 30/06/2015 BANK OF GREECE HEBIC BRANCH NAME AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE NUMBER / FAX 0100001 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARIAT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202049, fax: 2103226371 0100002 HEAD OFFICE TENDER AND ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS PROCUREMENT SECTION tel.: 2103203473, fax: 2103231691 0100003 HEAD OFFICE HUMAN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS RESOURCES SECTION tel.: 2103202090, fax: 2103203961 0100004 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202198, fax: 2103236954 0100005 HEAD OFFICE PAYROLL ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202096, fax: 2103236930 0100007 HEAD OFFICE SECURITY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202101, fax: 210 3204059 0100008 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION A tel.: 2103205154, fax: …… 0100009 HEAD OFFICE BOOK ENTRY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202620, fax: 2103235747 0100010 HEAD OFFICE ARCHIVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202206, fax: 2103203950 0100012 HEAD OFFICE RESERVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT BACK UP SECTION tel.: 2103203766, fax: 2103220140 0100013 HEAD OFFICE FOREIGN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS SECTION tel.: 2103202895, fax: 2103236746 0100014 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION B tel.: 2103205041, fax: …… 0100015 HEAD OFFICE PAYMENT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS SYSTEMS OVERSIGHT SECTION tel.: 2103205073, fax: …… 0100016 HEAD OFFICE ESCB PROJECTS CHALANDRI 341, Mesogeion Ave., 152 31 CHALANDRI AUDIT SECTION tel.: 2106799743, fax: 2106799713 0100017 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENTARY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

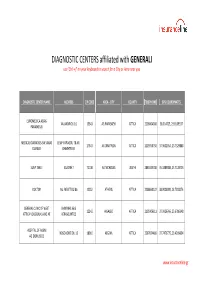

DIAGNOSTIC CENTERS Affiliated with GENERALI Use 'Ctrl + F' on Your Keyboard to Search for a City Or Area Near You

DIAGNOSTIC CENTERS affiliated with GENERALI use 'Ctrl + f' on your keyboard to search for a City or Area near you DIAGNOSTIC CENTER NAME ADDRESS ZIP CODE AREA - CITY COUNTY TELEPHONE GPS COORDINATES EUROMEDICA AGIAS XALANDRIOU 16 15343 AG PARASKEVI ATTICA 2106004000 38.014925, 23.8169337 PARASKEVIS MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS-SALVARAS LEWF.PAPAGOU 78 AG. 17343 AG DIMITRIOS ATTICA 2109750750 37.9602054, 23.7529888 IOANNIS DHMHTRIOS SUNY TABLE KAZANH 7 72100 AG NICHOLAS LASITHI 2841023700 35.1883088, 25.7128723 DOCTOR AG. MELETIOU 86 11252 ATHENS ATTICA 2108660222 38.0003909, 23.7318274 GENERAL CLINIC OF WEST SMYRNHS 36 & 12242 AIGALEO ATTICA 2105906611 37.9926766, 23.6786348 ATTICA VOUGIOUKLAKIO AE KERASOUNTOS HOSPITAL OF AIGINI NOSOKOMEIOU 10 18010 AEGINA ATTICA 2297024489 37.7473775, 23.4299604 AG.DIONUSIOS www.insuranceline.gr ELIKHS 34 KAI AIDIALEWS RADIOGRAPHY OF AEGEAN 25100 AIGIO ACHAIA 2691062700 38.2484992, 22.0911009 88 EUROMEDICA DHMHTRAS 21 68100 ALEXANDROUPOLI EVROS 2551089990 40.8491364, 25.8650806 ALEXANDROUPOLIS BIOCARE MEDICAL CENTER OF L. VOULIAGMENHS 562 17456 ALIMOS ATTICA 2109949562 37.9165572, 23.7440684 ALIMOS SYNCHRONOS ASKLIPIOS SA OTHWNOS 1 17455 ALIMOS ATTICA 2109821200 37.9208608, 23.7062464 EUROMEDICA AMPELOKIPON MESOGEIWN 2-4 11523 AMPELOKIPI ATTICA 2107470700 37.9847187, 23.7605037 EUROMEDICA AMPELOKIPON MARATHWNOS 14 56121 AMPELOKIPI THESSALONIKI 2310720020 40.6532014, 22.9193792 L.KHFISIAS 98 & ERYTHROU ORASIS AMPELOKIPON 11526 AMPELOKIPI ATTICA 2106998961 37.9927348, 23.7676253 STAVROU 2 ATHANASIADOU 9 & ATHENS EUROCLINIC 11521 AMPELOKIPI, ATHENS ATTICA 2106416600 37.9861342, 23.7564033 PARODOS D.SOUTSOU HARD ANASTASIOS AG. KWNSTANTINOU 4 21200 ARGOS ARGOLIDA 2751069201 37.6333241, 22.7300156 www.insuranceline.gr SOUHDIAS & GAKIS MICHAEL 28100 ARGOSTOLI KEPHALONIA 2671023451 38.1689764, 20.4931264 THEMISTOKLEOUS ASPROPYRGOS IONIA -EUROMEDICA PRIVATE 17o XLM N.E.O. -

EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER the GOVERNMENT of GREECE • Follow up to Collective Complaints • Complementary Information on Article

28/08/2015 RAP/Cha/GRC/25(2015) EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER 25th National Report on the implementation of the European Social Charter submitted by THE GOVERNMENT OF GREECE Follow up to Collective Complaints Complementary information on Articles 11§2 and 13§4 (Conclusions 2013) __________ Report registered by the Secretariat on 28 August 2015 CYCLE XX-4 (2015) 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter Follow-up to the decisions of the European Committee of Social Rights relating to Collective Complaints (2000 – 2012) Ministry of Labour, Social Security & Social Solidarity May 2015 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Collective Complaint 8/2000 “Quaker Council for European Affairs v. Greece” .......... 4 2. Collective Complaints (a) 15/2003, “European Roma Rights Centre [ERRC] v. Greece” & (b) 49/2008, “International Centre for the Legal Protection for Human Rights – [INTERIGHTS] v. Greece” ........................................................................................................ 8 3. Collective Complaint 17/2003 “World Organisation against Torture [OMCT] v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Collective Complaint 30/2005 “Marangopoulos Foundation for Human Rights v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 19 5. Collective Complaint “General Federation of Employees of the National Electric -

Piraeus Bank Sustainable Development Report 2016

The collection and presentation of the content in the 2016 Sustainable Development Report are the product of the work of all units of Piraeus Bank and its subsidiaries in Greece and abroad. Concept & Design MNP Actualization, Layout & Production Management Easy dot Printing Pressious Arvanitidis The 2016 Sustainable Development Report of Piraeus Bank was printed on Munken Pure Rough paper, obtained by environmentally-friendly processes. FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council®), Its mission is to promote environmentally responsible, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests. The 2016 Sustainable Development Report of Piraeus Bank is available online at: www.piraeusbankgroup.com/en/investors/financials/annual-reports and as an iOS & Android tablet Application at “Piraeus Group Kiosk”. Hard copies of the Report are available upon request to the Business Planning & IR Group: 4, Amerikis Str., GR-105 64, Athens, Τ: 210 3335026, [email protected] Last update of Piraeus Bank Sustainable Development Report: May 31, 2017 Sustainable Development Report 2016 www.piraeusbankgroup.com A new day for the world. Scheduled to last 24 hours, destined to be the day after yesterday, the day before tomorrow. Rising with new light, new colours. And a new century for Piraeus Bank. One hundred years of such new days, successive beginnings every 24 hours, whose colours set the tone and chart a course that is steady, a bright course - almost dazzling. And tomorrow, we will be here again, full of admiration for whatever -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Transport and Networks

Kifissia M t . P e Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT METRO LINES NETWORK Operating Lines Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1 Melissia PEFKI LINE 2 Kamatero MAROUSSI LINE 3 Iraklio Extensions IRAKLIO Penteli LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION NERANTZIOTISSA OTE AG.NIKOLAOS Nea LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Filadelfia NEA LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN IONIA Maroussi IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli Parking Facility - Attiko Metro Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia Ionia ILION Aghioi OLYMPIAKO "®P Operating Parking Facility STADIO Anargyri "®P Scheduled Parking Facility PERISSOS Nea PALATIANI Halkidona SUBURBAN RAILWAY NETWORK SIDERA Suburban Railway DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei "®P Suburban Railway Section also used by Metro o Halandri "®P e AGHIOS HALANDRI l P "® ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Kallitechnoupoli a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI GALATSI Aghia . PATISSIA Peristeri P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini ANTONIOS NIKOLAOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera "®P PANEPISTIMIO MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS KERAMIKOS THISSIO EVANGELISMOS ZOGRAFOU Nikea SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios PAGRATI KESSARIANI Ioannis ACROPOLI NEAR EAST Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX KALITHEA TAVROS "®P NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSCHATO Peania IOANNIS o Dafni t Moschato Ymittos Kallithea ANO t Drapetsona i PIRAEUS DAFNI ILIOUPOLI FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Networking UNDERGROUND Archaeological and Cultural Sites: the CASE of the Athens Metro

ing”. Indeed, since that time, the archaeological NETWORKING UNDERGROUND treasures found in other underground spaces are very often displayed in situ and in continu- ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND ity with the cultural and archaeological spaces of the surface (e.g. in the building of the Central CULTURAL SITES: THE CASE Bank of Greece). In this context, the present paper presents OF THE ATHENS METRO the case of the Athens Metro and the way that this common use of the underground space can have an alternative, more sophisticated use, Marilena Papageorgiou which can also serve to enhance the city’s iden- tity. Furthermore, the case aims to discuss the challenges for Greek urban planners regarding the way that the underground space of Greece, so rich in archaeological artifacts, can become part of an integrated and holistic spatial plan- INTRODUCTION: THE USE OF UNDERGROUND SPACE IN GREECE ning process. Greece is a country that doesn’t have a very long tradition either in building high ATHENS IN LAYERS or in using its underground space for city development – and/or other – purposes. In fact, in Greece, every construction activity that requires digging, boring or tun- Key issues for the Athens neling (public works, private building construction etc) is likely to encounter an- Metropolitan Area tiquities even at a shallow depth. Usually, when that occurs, the archaeological 1 · Central Athens 5 · Piraeus authorities of the Ministry of Culture – in accordance with the Greek Archaeologi- Since 1833, Athens has been the capital city of 2 · South Athens 6 · Islands 3 · North Athens 7 · East Attica 54 cal Law 3028 - immediately stop the work and start to survey the area of interest. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials Figure S1. Temperature‐mortality association by sector, using the E‐OBS data. Municipality ES (95% CI) CENTER Athens 2.95 (2.36, 3.54) Subtotal (I-squared = .%, p = .) 2.95 (2.36, 3.54) . EAST Dafni-Ymittos 0.56 (-1.74, 2.91) Ilioupoli 1.42 (-0.23, 3.09) Kessariani 2.91 (0.39, 5.50) Vyronas 1.22 (-0.58, 3.05) Zografos 2.07 (0.24, 3.94) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.689) 1.57 (0.69, 2.45) . NORTH Aghia Paraskevi 0.63 (-1.55, 2.87) Chalandri 0.87 (-0.89, 2.67) Galatsi 1.71 (-0.57, 4.05) Gerakas 0.22 (-4.07, 4.70) Iraklio 0.32 (-2.15, 2.86) Kifissia 1.13 (-0.78, 3.08) Lykovrisi-Pefki 0.11 (-3.24, 3.59) Marousi 1.73 (-0.30, 3.81) Metamorfosi -0.07 (-2.97, 2.91) Nea Ionia 2.58 (0.66, 4.54) Papagos-Cholargos 1.72 (-0.36, 3.85) Penteli 1.04 (-1.96, 4.12) Philothei-Psychiko 1.59 (-0.98, 4.22) Vrilissia 0.60 (-2.42, 3.71) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.975) 1.20 (0.57, 1.84) . PIRAEUS Aghia Varvara 0.85 (-2.15, 3.94) Keratsini-Drapetsona 3.30 (1.66, 4.97) Korydallos 2.07 (-0.01, 4.20) Moschato-Tavros 1.47 (-1.14, 4.14) Nikea-Aghios Ioannis Rentis 1.88 (0.39, 3.39) Perama 0.48 (-2.43, 3.47) Piraeus 2.60 (1.50, 3.71) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.580) 2.25 (1.58, 2.92) .