Character Displacement in Giant Rhinoceros Beetles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 It's All Geek to Me: Translating Names Of

IT’S ALL GEEK TO ME: TRANSLATING NAMES OF INSECTARIUM ARTHROPODS Prof. J. Phineas Michaelson, O.M.P. U.S. Biological and Geological Survey of the Territories Central Post Office, Denver City, Colorado Territory [or Year 2016 c/o Kallima Consultants, Inc., PO Box 33084, Northglenn, CO 80233-0084] ABSTRACT Kids today! Why don’t they know the basics of Greek and Latin? Either they don’t pay attention in class, or in many cases schools just don’t teach these classic languages of science anymore. For those who are Latin and Greek-challenged, noted (fictional) Victorian entomologist and explorer, Prof. J. Phineas Michaelson, will present English translations of the scientific names that have been given to some of the popular common arthropods available for public exhibits. This paper will explore how species get their names, as well as a brief look at some of the naturalists that named them. INTRODUCTION Our education system just isn’t what it used to be. Classic languages such as Latin and Greek are no longer a part of standard curriculum. Unfortunately, this puts modern students of science at somewhat of a disadvantage compared to our predecessors when it comes to scientific names. In the insectarium world, Latin and Greek names are used for the arthropods that we display, but for most young entomologists, these words are just a challenge to pronounce and lack meaning. Working with arthropods, we all know that Entomology is the study of these animals. Sounding similar but totally different, Etymology is the study of the origin of words, and the history of word meaning. -

A Passion for Rhinoceros and Stag Beetles in Japan

SCARABS CZ CN MNCHEM, NBYS QCFF WIGY. Occasional Issue Number 67 Print ISSN 1937-8343 Online ISSN 1937-8351 September, 2011 A Passion for Rhinoceros and Stag Beetles WITHIN THIS ISSUE in Japan Dynastid and Lucanid Enthusiasm in Japan ........ 1 by Kentaro Miwa University of Nebraska-Lincoln Bug People XXIV ........... 10 Department of Entomology In Past Years XLVI ......... 11 [email protected] Guatemala Scarabs IV ... 20 BACK ISSUES Available At These Sites: Coleopterists Society www.coleopsoc.org/de- fault.asp?Action=Show_ Resources&ID=Scarabs University of Nebraska A large population of the general public in Japan enjoys collecting and www-museum.unl.edu/ rearing insects. Children are exposed to insects at early ages because their research/entomology/ parents are interested in insects. My son went on his first collecting trip Scarabs-Newsletter.htm on a cool day in March in Nebraska when he was four months old. EDITORS I am from Shizuoka, Japan. I am currently pursuing my Ph.D in En- Rich Cunningham tomology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and studying biology [email protected] and applied ecology of insets in cropping systems. Among many insect Olivier Décobert taxa I am interested in, dynastines and lucanids are my favorite groups. [email protected] I have enjoyed collecting and rearing these beetles throughout my life. Barney Streit I began collecting beetles with my parents and grandparents when barneystreit@hotmail. com I was two years old. When I was about six, I learned to successfully rear some Japanese species. Since I came to the United States, I have been enjoying working with American species. -

Spineless Spineless Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E

Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Spineless Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates of the world’s Status and trends Spineless Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates Edited by Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Disclaimer The designation of the geographic entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expressions of any opinion on the part of ZSL, IUCN or Wildscreen concerning the legal status of any country, territory, area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation Collen B, Böhm M, Kemp R & Baillie JEM (2012) Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates. Zoological Society of London, United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-900881-68-8 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (paperback) 978-0-900881-70-1 Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates (online version) Editors Ben Collen, Monika Böhm, Rachael Kemp and Jonathan E. M. Baillie Zoological Society of London Founded in 1826, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is an international scientifi c, conservation and educational charity: our key role is the conservation of animals and their habitats. www.zsl.org International Union for Conservation of Nature International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) helps the world fi nd pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. www.iucn.org Wildscreen Wildscreen is a UK-based charity, whose mission is to use the power of wildlife imagery to inspire the global community to discover, value and protect the natural world. -

Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) and the Separation of Dynastini and Oryctini

Chromosome analyses challenge the taxonomic position of Augosoma centaurus Fabricius, 1775 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) and the separation of Dynastini and Oryctini Anne-Marie DUTRILLAUX Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, UMR 7205-OSEB, case postale 39, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) Zissis MAMURIS University of Thessaly, Laboratory of Genetics, Comparative and Evolutionary Biology, Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 41221 Larissa (Greece) Bernard DUTRILLAUX Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, UMR 7205-OSEB, case postale 39, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) Dutrillaux A.-M., Mamuris Z. & Dutrillaux B. 2013. — Chromosome analyses challenge the taxonomic position of Augosoma centaurus Fabricius, 1775 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) and the separation of Dynastini and Oryctini. Zoosystema 35 (4): 537-549. http://dx.doi.org/10.5252/z2013n4a7 ABSTRACT Augosoma centaurus Fabricius, 1775 (Melolonthidae: Dynastinae), one of the largest Scarabaeoid beetles of the Ethiopian Region, is classified in the tribe Dynastini MacLeay, 1819, principally on the basis of morphological characters of the male: large frontal and pronotal horns, and enlargement of fore legs. With the exception of A. centaurus, the 62 species of this tribe belong to ten genera grouped in Oriental plus Australasian and Neotropical regions. We performed cytogenetic studies of A. centaurus and several Asian and Neotropical species of Dynastini, in addition to species belonging to other sub-families of Melolonthidae Leach, 1819 and various tribes of Dynastinae MacLeay, 1819: Oryctini Mulsant, 1842, Phileurini Burmeister, 1842, Pentodontini Mulsant, 1842 and Cyclocephalini Laporte de Castelnau, 1840. The karyotypes of most species were fairly alike, composed of 20 chromosomes, including 18 meta- or sub-metacentric autosomes, one acrocentric or sub-metacentric X-chromosome, and one punctiform Y-chromosome, as that of their presumed common ancestor. -

Organisms That May Be Imported Without a Permit, See Section 7 (1) A)

Appendix II - organisms that may be imported without a permit, see section 7 (1) a). General condition: The import must be in accordance with the due care requirements in chapter V. Scientific name Norwegian/English name Condition Vertebrata Virveldyr; Vertebrates Mammalia (Klasse) Pattedyr; Mammals Camelidae Kameldyr Lama glama L., 1758 Lama; Llama Only for agricultural purposes. Vicugna pacos L., 1758 Alpakka; Alpaca Only for agricultural purposes. Canidae Hundefamilien; Canids Vulpes vulpes (L., 1758) Sølvrev; Silver Fox From breeding. Only Silver Foxes and crossings between Silver Fox and Arctic Fox/Polar Fox for fur famring in secured facilities. Vulpes lagopus (L., 1758) Blårev; Domesticated From breeding. Only Arctic syn. Alopex lagopus (L., Arctic Fox, Polar Fox Fox/Polar Fox and 1758) crossings between Arctic Fox/Polar Fox and Silver Fox for fur farming in secured facilities. Chinchillidae Chinchillafamilien; Chinchillas and Viscachas Chinchilla lanigera Chinchilla; Chinchilla, Domesticated. (Molina, 1782) Long-tailed Chinchilla Cricetidae Hamsterfamilien; Cricetids Mesocricetus auratus Gullhamster; Golden Domesticated. Waterhouse, 1839 Hamster Cricetulus griseus Milne- Kinesisk hamster; Chinese Domesticated. Edwards, 1867 Hamster Phodopus campbelli Campbells (stripet) Domesticated, including (Thomas, 1905) dverghamster; Campbell’s crossings with Phodopus Russian Dwarf Hamster sungorus. 1 Appendix II - organisms that may be imported without a permit, see section 7 (1) a). General condition: The import must be in accordance with the due care requirements in chapter V. Scientific name Norwegian/English name Condition Phodopus sungorus (Pallas, Russisk (sibirsk) Domesticated, including 1773) dverghamster; Siberian crossings with Phodopus Hamster, Djungarian campbelli. Hamster Phodopus roborovski Roborovski dverghamster; Domesticated. (Satunin, 1903) Roborovski Hamster Caviidae Marsvinfamilien; Guinea Pigs Cavia porcellus (L., 1758) Marsvin; Guinea Pig Domesticated. -

Authorsindex

AUTHORSINDEX ARROW, G. J. 153. HUXLEY, J. 103, 125, 153. BAKER, C. S. 59. ILLIGER, J. C. 27. BATES, H. W. 76, 153. JUDULIEN, F. 55, 154. BATESON, W. 60, 102, 153. LAMEERE, A. 102, 133, 136, 139, 154. BEEBE, W. 61 et seq., 132, 153. LOCKET, G. H. 126, 154. BEESON, C. F. C. 37, 153. MABTERLINCK, M. 29. BENNETT, A. L. 63, 153. MAIN, H. 11, 43, 154. BLAIR, K. G. 1. MANEE, A. H. 45, 57, 59, 154. BRINDLEY, H. H. 60, 102, 153. MARSHALL, SIR G. A. K. 1, 75. BRISTOWE, W. S. 126, 153. MORLEY, B. D. W. 123, 154. CHAMPY, C. 138, 153. MULSANT, E. 27, 154. CHAPMAN, T. A. 34 et seq., 38, 153. OHAUS, F. 29 et seq., 54, 56 et seq., CORBIN, G. B. 42, 153. 69, 98, 154. CORNELIUS, C. 141. PEARSE, A. S. 31, 154. CUNNINGHAM, J. T. 124, 127, 153. PECKHAM, G. & E. 125, 154. DAGUERRE, J. B. 55, 153. PERCIVAL, R. B. 112. DARWIN, C. 2, 3, 24, 65, 79, 103, 108, PERRIS, E. 79. 116 et seq., 132, 139, 153. POCOCK, R. I. 1. DOANE, R. W. 58, 153. REICHENAU, W. VON. 118, 154. ELTRINGHAM, H. 119. RODWAY, F. A. 48. EMDEN,F.VAN. 1. SAUNDERS, C. J. 48, 154. FASRE, J. H. 8, 11, 27, 28, 43, 49 et SCHREINER, J. 39, 154. seq., 74, 153. SLOANE, H. 53. FRASER, F. C. 31. STROHMEYER, H. 13, 154. GEDDES, SIR P. 118, 139, 154. SYMS, E. 74. HEYMONS, R. 31, 153. THOMSON, SIR J. A. 118, 139, 154. -

WAZA News 3/12

August 3/12 2012 Arthropods in Zoos | p 2 Atlantic Forest: Corridors For Life | p 14 No Need to Kiss This Frog: HRH Prince Charles | p 22 ). Nicrophorus americanus – Roger Williams Park Zoo in Rhode Island Williams Park – Roger American burying beetle ( © Lou Perrotti WAZA news 3/12 Gerald Dick Contents Editorial Arthropods .............................. 2 Dear WAZA members and friends! Invertebrate Conservation ........ 5 My Career: The last months have been amongst Shigeyuki Yamamoto ...............9 the most busy ones for the executive WAZA Interview: office. The exciting programme for Ray Morrison ......................... 12 our 67th Annual Conference has been Brazil’s Great finalized, a CO2 compensation scheme Atlantic Forest ....................... 14 for zoos and aquariums has been put WAZA Elected together and offered to WAZA mem- on IATA’s LAPB ...................... 16 bers, a new edition of the WAZA maga- Book Reviews ........................ 18 zine – entitled fighting extinction – with Announcements .................... 19 a focus on “extinct in the wild” clas- No Need to Kiss This Frog ........22 sified species has been published, the Partnerships to WAZA project in support of the decade Fight Amphibian Crisis .............23 on biodiversity with the survey module Update on awareness has started, WAZA is International Studbooks ......... 24 now represented on IATA’s live animals Help for Illegal Scorpions ........ 24 and perishables advisory panel, WAZA WAZA Projects and the world zoos and aquariums Mono Tocón........................... 25 have been dignified by Jane Goodall Western Derby Eland ............. 26 and HRH Charles, Prince of Whales and Tamanduá ..............................27 WAZA has been gifted a commemora- New Member Applications ...... 29 tive design by Jonathan Woodward, © Carmel Croukamp a commended finalist of the “BBC Wild- Gerald Dick in snakepit at Foz Iguazu. -

Some Conspicuous Beetles of Sulawesi

Some conspicuous beetles of Sulawesi by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Topics in Lexicography, no. 35 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangLexTopics035-v1 2 LANGUAGES Language of materials : English ABSTRACT In this paper I draw attention to seven kinds of beetles. Each is conspicuous by its large size and may bear its own name in the local language. An appendix lists a few additional kinds of beetles, giving their English and Indonesian common names and scientific identification. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction; Atlas beetle; Coconut rhinoceros beetle; Other rhinoceros beetles; Stag beetles; Dung beetles; Longhorn beetles; Palm weevils; Appendix; References. VERSION HISTORY Version 1 [11 June 2020] Drafted February 2012; revised October 2013 and March 2015; revised and formatted for publication February 2020. © 2020 by David Mead Text is licensed under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International license. Images are licensed as individually noted. Some conspicuous beetles of Sulawesi by David Mead Introduction Beetles are an insect order (Coleoptera) known for their hardened forewings, called elytra. Worldwide there are more than 400,000 described species of beetles, more than any other order of plant or animal. Whilst a comprehensive guide to the beetles of Sulawesi lies beyond my meager ability, I would like to bring your attention to at least the following seven kinds of beetles. Each is conspicuous by its large size and may bear its own name in the local language. In an appendix I list some additional beetles along with their Indonesian and English common names, scientific classifications, and brief descriptions. -

List of Species Exempted from Import Permit Requirement Pdf, 133.2

Vedlegg 1. Arter som i forskrift om fremmede organismer er unntatt fra kravet om tillatelse ved innførsel: Appendix 1. Species exempted from import permit requirement under the Regulation on alien species: Vitenskapelig navn Trivialnavn Vilkår Arthropoda Leddyr; Arthropods Arachnida (Klasse) Edderkopper; Spiders Theraphosidae Theraposinae Amerikanske taranteller; (Underfamilie) New World Tarantulas Aphonopelma hentzi Texas Brown Tarantula (Girard, 1852) Aphonopelma seemanni Striped-knee Tarantula (F.O. P.-Cambridge, 1897) Aphonopelma texense Rio Grande Copper (Simon, 1891) Tarantula Chromatopelma Greenbottle Blue Tarantula cyaneopubescens (Strand, 1907) Cyriocosmus elegans Trinidad Dwarf Tiger (Simon, 1889) Rump Euathlus pulcherrimaklaasi Metallic Femur Beauty (Schmidt, 1991) Euathlus truculentus Chilean Beautiful (Ausserer, 1875) Euathlus vulpinus (Karsch, Chilean Ocellated 1880) Eupalaestrus campestratus Pink Zebra Beauty (Simon, 1891) Grammostola aureostriata Chaco Golden Knee (Schmidt & Bullmer, 2001) Grammostola burzaquensis Argentinean Rose Ibarra, 1946 Tarantula Grammostola grossa Argentina Giant Tawny (Ausserer, 1871) Red, Pampas Tawny Red, Giant Tawny Red Grammostola iheringi Entre Rios Tarantula (Keyserling, 1891) Grammostola mollicoma Brazilian Giant Tawny Red (Ausserer, 1875) Grammostola pulchra Brazilian Black Tarantula Mello- Leitao, 1921 Grammostola rosea Chilean Rose Hair, Chilean (Walckenaer, 1837) Rose Vitenskapelig navn Trivialnavn Vilkår Lasiodora difficilis Mello- Fiery Redrump Leitao, 1921 Lasiodora klugi (C.L. Baja -

Appendix II – Organisms That Can Be Imported Without a Permit, See Section 7 (1) A)

Appendix II – organisms that can be imported without a permit, see section 7 (1) a) General condition: The import shall be carried out in accordance with the due care requirements set out in Chapter V and the rest of the Regulations, as well as other applicable law, including the Regulations of 15 November 2002 No. 1276 for the implementation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) of 3 March 1973. Scientific name Norwegian/English name Condition Vertebrata Virveldyr; Vertebrates Mammalia (Klasse) Pattedyr; Mammals Camelidae Kameldyr Lama glama L., 1758 Lama; Llama Only for agricultural purposes. Vicugna pacos L., 1758 Alpakka; Alpaca Only for agricultural purposes. Canidae Hundefamilien; Canids Vulpes vulpes (L., 1758) Sølvrev; Silver Fox From breeding. Only Silver Foxes and crossings between Silver Fox and Arctic Fox/Polar Fox for fur farming when the keeping is carried out in accordance with the Regulations 17 March 2011 relation to the keeping of animals for fur production. Vulpes lagopus (L., 1758) Blårev; Domesticated From breeding. Only Arctic syn. Alopex lagopus (L., Arctic Fox, Polar Fox Fox/Polar Fox and 1758) crossings between Arctic Fox/Polar Fox and Silver Fox for fur farming when the keeping is carried out in accordance with the Regulations 17 March 2011 relation to the keeping of animals for fur production. Chinchillidae Chinchillafamilien; Chinchillas and Viscachas Chinchilla lanigera Chinchilla; Chinchilla, Domesticated. (Molina, 1782) Long-tailed Chinchilla 1 Appendix II – organisms that can be imported without a permit, see section 7 (1) a) General condition: The import shall be carried out in accordance with the due care requirements set out in Chapter V and the rest of the Regulations, as well as other applicable law, including the Regulations of 15 November 2002 No. -

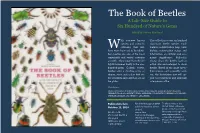

The Book of Beetles a Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred of Nature's Gems

The Book of Beetles A Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred of Nature's Gems Edited by Patrice Bouchard ith 350,000 known This collection covers six hundred species, and scientific significant beetle species. Each W estimates that mil- features a distribution map, basic lions more have yet to be identi- biology, conservation status, and fied, beetles are one of the most information on cultural and eco- remarkable and varied creatures nomic significance. Full-color on earth. They range from the de- photos show the beetles both at lightful summer firefly to the one- actual size and enlarged to show hundred-gram Goliath beetle. details. Based in the most up-to- Beetles offer a dazzling array of date science and accessibly writ- shapes, sizes, and colors that en- ten, the descriptive text will ap- tice scientists and collectors across peal to researchers and armchair the globe. coleopterists alike. Contributors: PATRICE BOUCHARD, YVES BOUSQUET, CHRISTOPHER CARLTON, MARIA LOURDES CHAMORRO, HERMES E. ESCALONA, ARTHUR V. EVANS, ALEXANDER S. KONSTANTINOV, RICHARD A. B. LESCHEN, STÉPHANE LE TIRANT, AND STEVEN W. LINGAFELTER. Publication date For a review copy or other To place orders in the October 15, 2014 publicity inquiries, please United States or Canada, contact: please contact your local $55.00, cloth Lauren Salas University of Chicago Press 978-0-226-08275-2 Promotions Manager, sales representative or contact the University of 656 pages University of Chicago Press, Chicago Press by phone at 2400 color plates [email protected] 773-702-0890 1-800-621-2736. 7 1/8 x 10 1/2 THE BOOK OF BEETLES THE BOOK OF BEETLES A LIFE-SIZE GUIDE TO SIX HUNDRED OF NATURE’S GEMS EDITOR PATRICE BOUCHARD CONTRIBUTORS PATRICE BOUCHARD, YVES BOUSQUET, CHRISTOPHER CARLTON, MARIA LOURDES CHAMORRO, HERMES E. -

Edible Forests Insect

Forest insects as food: humans bite back / Proceedings of a workshop on Asia-Pacific resources and their potential for development RAP PUBLICATION 2010/02 Forest insects as food: humans bite back Proceedings of a workshop on Asia-Pacific resources and their potential for development 19-21 February 2008, Chiang Mai, Thailand Edited by Patrick B. Durst, Dennis V. Johnson, Robin N. Leslie and Kenichi Shono FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Bangkok, Thailand 2010 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ISBN 978-92-5-106488-7 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial users will be authorized free of charge. Repro- duction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials and all other queries on rights and licenses, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge, Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2010 Cover design: Chanida Chavanich For copies of the report, write to: Patrick B. Durst Senior Forestry Officer FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific 39 Phra Atit Road Bangkok 10200 Thailand Tel: (66-2) 697 4000 Fax: (66-2) 697 4445 E-mail: [email protected] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand ii Foreword In this fast-paced modern world, it is sometimes easy to lose sight of valuable traditional knowledge and practices.