FRIENDLY FIRE by Steve Pyne § the Warm Fire Started from a Lightning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Gardener AUGUST 2020 FINAL

Do worms make New EGO Autumn is the new good compost? chainsaw Spring! page 19 page 3 page 11 Local Gardener The UK’s only newspaper for Gardeners National allotment week! P22 P10 Green-tech has you covered! Cobra has once again It is self-propelled, has four With four speeds, a generous petrol engine that utilises the the need to pull the recoil and The mower has a expanded its range of speeds and also has the 21” cutting width and a latest technology to ensure makes starting even easier. recommended retail price of lawnmowers with the option for both mulching and grassbag with a 65-litre optimal torque and £400.00 introduction of the new side discharge to dispose of capacity it is designed for efficiency. Cobra products are available MX534SPCE mower. cuttings. medium to large gardens, up to buy online at An optional swing tip blade to approximately 600 m2. It also features an electric www.cobragarden.co.uk or is available to use with the It is a 21” petrol powered This multi-feature mower is starting system to ease via a network of expert Cobra MX534SPCE mower that combines many the ultimate in power, style It features a quiet yet starting the petrol engine. dealers across the UK. Lawnmower. The 4 bladed top-of-range features. and reliability in the garden. powerful 4-stroke Cobra The electric button replaces swing tip system can be P2 P18 August 2020 online at www.localgardener.org August 2020 Local Gardener How to contact us at the editorial office: How to take out an advertisement Phone 07984 11 2537 email [email protected] Phone 07984 11 2537 email [email protected] Write to Local Gardener Newspaper, Kemp House, 152-160 City Rd, London EC1V 2NX Write to Local Gardener Newspaper, Kemp House, 152-160 City Rd, London EC1V 2NX FRONT PAGE GREENMECH INTRODUCE NEW EVO 165P SUB-750 used for a more efficient cut. -

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management PMS 902 April 2021 NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management April 2021 PMS 902 The NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management, assists participating agencies of the NWCG to constructively work together to provide effective execution of each agency’s incident business management program by establishing procedures for: • Uniform application of regulations on the use of human resources, including classification, payroll, commissary, injury compensation, and travel. • Acquisition of necessary equipment and supplies from appropriate sources in accordance with applicable procurement regulations. • Management and tracking of government property. • Financial coordination with the jurisdictional agency and maintenance of finance, property, procurement, and personnel records, and forms. • Use and coordination of incident business management functions as they relate to sharing of resources among federal, state, and local agencies, including the military. • Documentation and reporting of claims. • Documentation of costs and cost management practices. • Administrative processes for all-hazards incidents. Uniform application of interagency incident business management standards is critical to successful interagency fire operations. These standards must be kept current and made available to incident and agency personnel. Changes to these standards may be proposed by any agency for a variety of reasons: new law or regulation, legal interpretation or opinion, clarification of meaning, etc. If the proposed change is relevant to the other agencies, the proponent agency should first obtain national headquarters’ review and concurrence before forwarding to the NWCG Incident Business Committee (IBC). IBC will prepare draft NWCG amendments for all agencies to review before finalizing and distributing. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

The West Australian Woodchip Industry Ha Chip

THE WEST AUSTRALIAN WOODCHIP INDUSTRY HA CHIP & PULP CO PTY LTD Report and Recommendations of the Environmental Protection Authority Environmental Protection Authority Perth, Hestern Australia Bulletin 329 July 1988 ISBN 0 7309 1828 9 ISSN 1030-0120 CONTENTS Page i SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS iii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. .BACKGROUND . 1 3. DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSAL 3 4. PUBLIC REVIEW 7 5. REVIEW OF CURRENT WOODCHIPPING OPERATIONS 7 5.1 EARLIER PREDICTIONS OF UlPACT 7 5.2 SUHHARY OF RESEARCH 10 5.3 REVIEW OF INVESTIGATIONS . 11 6. ASSESSHENT OF POTENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 12 6.1 INTRODUCTION . 12 6.2 PROVISION OF \olOODCHIP RESOURCE 14 6.2.1 INTEGRATED HARVESTING IN STATE FOREST 14 6.2.2 THINNINGS FRml STATE FOREST 25 6.2.3 \olOODCHIPPING OF SAIVMILL RESIDUES . 25 6.2.4 PLANTATIONS ESTABLISHED ON CLEARED PRIVATE PROPERTY 26 6.2.5 CLEARING OF RE~INANT NATIVE VEGETATION ON PRIVATE PROPERTY 27 6.3 \olOODCHIP PRODUCTION AND EXPORT 30 6.4 DURATION OF STATE APPROVALS 31 7. ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING 31 8. CONFLICT RESOLUTION 34 9. CONCLUSIONS 34 10. REFERENCES 36 11. GLOSSARY . 38 APPENDICES 1. Summary of Issues Raised in Submissions on the ERHP/draft EIS . .. ...... 44 2. List of Publications on the Forests of South \olestern Australia 66 3. List of Commitments made by WA Chip & Pulp Co. Pty Ltd in the Supplement to the ERHP . 85 i FIGURES Page 1. The Current Woodchip Licence Area 39 2. Projected Chiplog Sources from State Forest 1987-2009 40 3. HACAP's Sources of Chiplogs and Hoodchips 1975-2005 41 4. -

The-Plantation-Forestry-Sector-In-Mozambique-Community-Involvement-And-Jobs.Pdf

JOBS WORKING PAPER Issue No. 30 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Plantation Forestry Sector In Mozambique: Community Involvement And Jobs Public Disclosure Authorized Leonor Serzedelo de Almeida Christopher Delgado Public Disclosure Authorized S WORKA global partnership to create private sector jobs LET’ more & better THE PLANTATION FORESTRY SECTOR IN MOZAMBIQUE: COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT AND JOBS Leonor Serzedelo de Almeida Christopher Delgado The Let’s Work Partnership in Mozambique is made possible through a grant from the World Bank’s Jobs Umbrella Trust Fund, which is supported by the Department for International Development/UK AID, and the Governments of Norway, Germany, Austria, the Austrian Development Agency, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA. Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org. Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. -

What a Gully

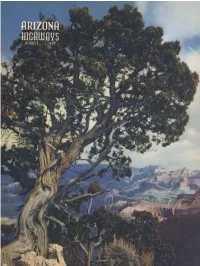

~~GOLLY9 WHAT A GULLY / History does not record the words spoken by Don Garcia Lopez de Cardenas, proud captain of Castile, that memorable day in 1540 when he and his companions looked into the Grand Canyon, the first Europeans to do so. In all probability those words were strong, soldierly expletives, although a footsore scribe, of a poetical bent, recorded for posterity and prying eyes in Spain that the buttes and towers of the Canyon which "appeared from above to be the height of a man were higher than the tower of the Cathedral of Seville." An apt description, my capitan! The gentle Father Garces came along in 1776 and was quite .impressed by the canyon, giving it the name of "Puerto de Bucareli" in honor of a great Viceroy of Spain. James 0. Pattie, trapper and mountain man, arrived at the canyon in 1826, the first American tourist to visit there. Unfortunately there were no comfortable Fred Harvey accommoda tions awaiting him and he was pretty disgusted .with the whole thing . "Horrid mountains ," he wrote . Lt . Joseph Ives , an explorer, came to the "Big Canyon" in 1857 and "paused in wondering delight" but found the region "altogether valueless. Ours has been the first and will doubtless be the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality ," was his studied opinion. But the lieutenant's feet probably were hurting him and he should be forgiven his hasty words . John Wesley Powell, twelve years later, arrived at the canyon the exc1tmg way - by boat down the Colorado. To him it was the "Grand" Canyon and so to all the world it has been ever since. -

ST6 Woodchipper

PT8 Woodchipper USER MANUAL ENGLISH 26/11/2018 Revision 1 Redwood Global Ltd, Unit 86, Livingstone Road, Walworth Business Park, Andover, Hampshire. SP10 5NS. United Kingdom P a g e | 1 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of machine .............................................................................................................. 4 Exterior component identification .......................................................................................... 5 Safety ................................................................................................................................... 6 Safe working...................................................................................................................... 6 Machine lifting ................................................................................................................... 7 DOs and DON’Ts .............................................................................................................. 8 Noise test information ........................................................................................................... 9 Machine operation .............................................................................................................. 10 Machine control panel, start/stop & operating settings ..................................................... 11 Feed speed adjustment .................................................................................................. -

1St Hour Add. Hour 1St Day 2Nd Day Add. Day AIR COMPRESSORS 8CFM Elec. Portable Sm. $15.00 $5.00 $35.00 $25.00 $15.00 17CFM Gas Lg

1st Hour Add. Hour 1st Day 2nd Day Add. Day AIR COMPRESSORS 8CFM Elec. Portable Sm. $15.00 $5.00 $35.00 $25.00 $15.00 17CFM Gas Lg. $20.00 $10.00 $60.00 $40.00 $20.00 200CFM Diesel Towable $50.00 $19.00 $125.00 $95.00 $65.00 AIR TOOLS AND HOSES 35 lb. Air Hammer $30.00 $7.50 $60.00 $45.00 $30.00 60 lb. Air Hammer $30.00 $7.50 $60.00 $45.00 $30.00 90 lb. Air Hammer $30.00 $7.50 $60.00 $45.00 $30.00 Texture Gun $10.00 $5.00 $30.00 $22.00 $15.00 Glitter Gun Hand - - - - $10.00 $5.00 $2.50 Frame Nailer Air $15.00 $3.75 $30.00 $23.00 $15.00 Sheating Stapler Air $15.00 $3.75 $30.00 $23.00 $15.00 Finish Nailer Air $15.00 $3.75 $30.00 $23.00 $15.00 Brad Nailer $15.00 $3.75 $30.00 $23.00 $15.00 Roof Nailer Air $15.00 $3.75 $30.00 $23.00 $15.00 Air Tank $5.00 $3.00 $17.00 $13.00 $8.00 Air Hose 3/4" 50' - - - - $8.00 $4.00 $2.00 Air Hose 3/8" 50' - - - - $5.00 $2.00 $1.00 APPLIANCE DOLLIES/MOVING EQUIPMENT Appliance Dolly $6.00 $3.00 $18.00 $13.00 $8.00 Appliance Dolly HD $8.00 $3.00 $20.00 $15.00 $10.00 Piano Dolly Upright $8.00 $4.00 $25.00 $15.00 $10.00 Piano Dolly 2 pc. -

Snohomish County 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan Volume II

Snohomish County 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan Volume II September 2020 Prepared for: 3000 Rockefeller Avenue Everett, WA 98201 Prepared by: Ecology & Environment, Inc. 333 SW Fifth Ave, Suite 608 Portland, OR 97204 View the Snohomish County Hazard Mitigation Plan online at: https://snohomishcountywa.gov/2429/Hazard-Mitigation-Plan SNOHOMISH COUNTY HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN, VOLUME 2 | 2020 UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents 1 Planning Partner Participation ........................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Planning Partnership .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2.1 Initial Solicitation and Letters of Intent ................................................................................ 1 1.2.2 Planning Partner Expectations .............................................................................................. 2 1.3 Annex Preparation ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.3.1 Templates .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.3.2 Workshops ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.3.3 Hazard Probability, Exposure, and Vulnerability -

Gcnp Sfra) Procedures Manual

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK SPECIAL FLIGHT RULES AREA (GCNP SFRA) PROCEDURES MANUAL 6/1/2016 US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK SPECIAL FLIGHT RULES AREA (GCNP SFRA) PROCEDURES MANUAL Revision 10 i U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK SPECIAL FLIGHT RULES AREA (GCNP SFRA) PROCEDURES MANUAL Revision 10 i U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Grand Canyon National Park Special Flight Rules Area (GCNP SFRA)Procedures Manual GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK SPECIAL FLIGHT RULES AREA Record of Revisions Revision Number Effective Date Date Entered Entered By Original 06/01/1995 06/01/1995 LAS FSDO One 06/02/1995 06/02/1995 LAS FSDO Two 06/12/1995 06/12/1995 LAS FSDO Three 11/25/1996 11/25/1996 LAS FSDO Four 08/01/1998 08/01/1998 LAS FSDO Five 11/01/1998 11/01/1998 LAS FSDO Six 05/04/2000 05/04/2000 LAS FSDO Seven 04/19/2001 04/19/2001 LAS FSDO Eight 06/24/2011 06/24/2011 LAS FSDO Nine 01/01/2016 12/01/2015 NEV FSDO Ten 06/01/2016 06/01/2016 NEV FSDO ii U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Grand Canyon National Park Special Flight Rules Area (GCNP SFRA) Procedures Manual List of Effective Pages PAGE # DATE REVISION PAGE # DATE REVISION i (Letter) 6/1/2016 10 2-21 6/1/2016 10 ii 6/1/2016 10 2-22 6/1/2016 10 iii 6/1/2016 10 2-23 6/1/2016 10 iv 6/1/2016 10 -

Initial Bison Herd Reduction

NATIONAL PARK Grand Canyon National Park U.S. Department of the Interior SERVICE Arizona National Park Service Initial Bison Herd Reduction ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT May 2017 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Initial Bison Herd Reduction Environmental Assessment Grand Canyon National Park May 2017 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION .................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 1 PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION ........................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 3 NPS AUTHORITY TO MANAGE WILDLIFE ................................................................................................. 4 COOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF THE HOUSE ROCK BISON HERD .......................................................... 4 ISSUES AND IMPACT TOPICS ...................................................................................................................... 6 Issues and Impact Topics Carried Forward for Additional Analysis .................................................... 7 House Rock Bison Herd ...................................................................................................................