Corvus Review: Fall 2015 Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Gardener AUGUST 2020 FINAL

Do worms make New EGO Autumn is the new good compost? chainsaw Spring! page 19 page 3 page 11 Local Gardener The UK’s only newspaper for Gardeners National allotment week! P22 P10 Green-tech has you covered! Cobra has once again It is self-propelled, has four With four speeds, a generous petrol engine that utilises the the need to pull the recoil and The mower has a expanded its range of speeds and also has the 21” cutting width and a latest technology to ensure makes starting even easier. recommended retail price of lawnmowers with the option for both mulching and grassbag with a 65-litre optimal torque and £400.00 introduction of the new side discharge to dispose of capacity it is designed for efficiency. Cobra products are available MX534SPCE mower. cuttings. medium to large gardens, up to buy online at An optional swing tip blade to approximately 600 m2. It also features an electric www.cobragarden.co.uk or is available to use with the It is a 21” petrol powered This multi-feature mower is starting system to ease via a network of expert Cobra MX534SPCE mower that combines many the ultimate in power, style It features a quiet yet starting the petrol engine. dealers across the UK. Lawnmower. The 4 bladed top-of-range features. and reliability in the garden. powerful 4-stroke Cobra The electric button replaces swing tip system can be P2 P18 August 2020 online at www.localgardener.org August 2020 Local Gardener How to contact us at the editorial office: How to take out an advertisement Phone 07984 11 2537 email [email protected] Phone 07984 11 2537 email [email protected] Write to Local Gardener Newspaper, Kemp House, 152-160 City Rd, London EC1V 2NX Write to Local Gardener Newspaper, Kemp House, 152-160 City Rd, London EC1V 2NX FRONT PAGE GREENMECH INTRODUCE NEW EVO 165P SUB-750 used for a more efficient cut. -

FRIENDLY FIRE by Steve Pyne § the Warm Fire Started from a Lightning

FRIENDLY FIRE by Steve Pyne § The Warm fire started from a lightning strike on June 8, 2006 a few miles south of Jacob Lake, between Highway 67 and Warm Springs (which gave the fire its name) and could easily have been extinguished with a canteen and a shovel. The North Kaibab instead declared it a Wildland Fire Use fire, and was delighted. Previous efforts with WFUs had occurred during the summer storm season and had yielded small, low-intensity burns that “did not produce desired effects.” The district had committed to boosting its burned acres and had engineered personnel transfers to make that happen. Since large fires historically occurred in the run-up to the summer monsoon season, when conditions were maximally hot, dry, and windy, the Warm fire promised to rack up the desired acres.1 For three days the fire behaved as hoped. On June 11 the district decided to request a Fire Use Management Team to help run the fire, which was now over a hundred acres and blowing smoke across the sole road to the North Rim, and so required ferrying vehicles under convoy. On June 13 the FUMT assumed command of the fire. Briefings included a warning that the fire could not be allowed to enter a region to the southeast which was a critical habitat for the Mexican spotted owl. The “maximum management area” allotted for the fire was 4,000 acres. That day the fire spotted across the highway, outside the prescribed zone. The FUMT and district ranger decided to seize the opportunity to allow the fire to grow and get some “bonus acres.” The prescribed zone was increased; then increased again as the fire, now almost 7,000 acres, crossed Forest Road 225, another prescribed border. -

NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management PMS 902 April 2021 NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management April 2021 PMS 902 The NWCG Standards for Interagency Incident Business Management, assists participating agencies of the NWCG to constructively work together to provide effective execution of each agency’s incident business management program by establishing procedures for: • Uniform application of regulations on the use of human resources, including classification, payroll, commissary, injury compensation, and travel. • Acquisition of necessary equipment and supplies from appropriate sources in accordance with applicable procurement regulations. • Management and tracking of government property. • Financial coordination with the jurisdictional agency and maintenance of finance, property, procurement, and personnel records, and forms. • Use and coordination of incident business management functions as they relate to sharing of resources among federal, state, and local agencies, including the military. • Documentation and reporting of claims. • Documentation of costs and cost management practices. • Administrative processes for all-hazards incidents. Uniform application of interagency incident business management standards is critical to successful interagency fire operations. These standards must be kept current and made available to incident and agency personnel. Changes to these standards may be proposed by any agency for a variety of reasons: new law or regulation, legal interpretation or opinion, clarification of meaning, etc. If the proposed change is relevant to the other agencies, the proponent agency should first obtain national headquarters’ review and concurrence before forwarding to the NWCG Incident Business Committee (IBC). IBC will prepare draft NWCG amendments for all agencies to review before finalizing and distributing. -

Women's History Month 2021

WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH 2021 SPOTLIGHT: CUIMC WOMEN The CUIMC Women’s Employee Resource Group would like to thank those who nominated Staff and/or Faculty women of influence at the medical center to be spotlighted during women’s history month. Many women in the workplace do not realize the level of influence and impact they have on the people around them. There are always misperceptions that we need some magic something to have an impact or to influence others. The fact of the matter is people see us, listen to us, and agree to do things for us more often than we realize. "Surround yourself only with people who are going to lift you higher"- Oprah Winfrey "The great gift of human beings is that we have the power of empathy"- Meryl Streep "Spread love everywhere you go. Let no one ever come to you without leaving happier"- Mother Teresa "I've always believed that one woman's success can only help another woman's success"- Gloria Vanderbilt WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH 2021 SPOTLIGHT: CUIMC WOMEN Maura Abbot, PhD, NP NOMINATOR’S COMMENTS Maura is an incredible mentor, professor, and leader. As someone who straddles the worlds of academic and clinical medicine, she demonstrates that opportunities for women in the workplace are endless. I wish every “ woman had a positive and uplifting role model like Maura! BEST ADVICE YOU HAVE RECEIVED I think the best professional advice I have ever received I heard twice once from a Nursing mentor and again from a physician colleague. They told me “know what you know, and more importantly know what you don’t know. -

The West Australian Woodchip Industry Ha Chip

THE WEST AUSTRALIAN WOODCHIP INDUSTRY HA CHIP & PULP CO PTY LTD Report and Recommendations of the Environmental Protection Authority Environmental Protection Authority Perth, Hestern Australia Bulletin 329 July 1988 ISBN 0 7309 1828 9 ISSN 1030-0120 CONTENTS Page i SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS iii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. .BACKGROUND . 1 3. DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSAL 3 4. PUBLIC REVIEW 7 5. REVIEW OF CURRENT WOODCHIPPING OPERATIONS 7 5.1 EARLIER PREDICTIONS OF UlPACT 7 5.2 SUHHARY OF RESEARCH 10 5.3 REVIEW OF INVESTIGATIONS . 11 6. ASSESSHENT OF POTENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 12 6.1 INTRODUCTION . 12 6.2 PROVISION OF \olOODCHIP RESOURCE 14 6.2.1 INTEGRATED HARVESTING IN STATE FOREST 14 6.2.2 THINNINGS FRml STATE FOREST 25 6.2.3 \olOODCHIPPING OF SAIVMILL RESIDUES . 25 6.2.4 PLANTATIONS ESTABLISHED ON CLEARED PRIVATE PROPERTY 26 6.2.5 CLEARING OF RE~INANT NATIVE VEGETATION ON PRIVATE PROPERTY 27 6.3 \olOODCHIP PRODUCTION AND EXPORT 30 6.4 DURATION OF STATE APPROVALS 31 7. ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING 31 8. CONFLICT RESOLUTION 34 9. CONCLUSIONS 34 10. REFERENCES 36 11. GLOSSARY . 38 APPENDICES 1. Summary of Issues Raised in Submissions on the ERHP/draft EIS . .. ...... 44 2. List of Publications on the Forests of South \olestern Australia 66 3. List of Commitments made by WA Chip & Pulp Co. Pty Ltd in the Supplement to the ERHP . 85 i FIGURES Page 1. The Current Woodchip Licence Area 39 2. Projected Chiplog Sources from State Forest 1987-2009 40 3. HACAP's Sources of Chiplogs and Hoodchips 1975-2005 41 4. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

The-Plantation-Forestry-Sector-In-Mozambique-Community-Involvement-And-Jobs.Pdf

JOBS WORKING PAPER Issue No. 30 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Plantation Forestry Sector In Mozambique: Community Involvement And Jobs Public Disclosure Authorized Leonor Serzedelo de Almeida Christopher Delgado Public Disclosure Authorized S WORKA global partnership to create private sector jobs LET’ more & better THE PLANTATION FORESTRY SECTOR IN MOZAMBIQUE: COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT AND JOBS Leonor Serzedelo de Almeida Christopher Delgado The Let’s Work Partnership in Mozambique is made possible through a grant from the World Bank’s Jobs Umbrella Trust Fund, which is supported by the Department for International Development/UK AID, and the Governments of Norway, Germany, Austria, the Austrian Development Agency, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA. Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org. Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. -

Quiet Talks on Service

Quiet Talks on Service Author(s): Gordon, Samuel Dickey (1859-1936) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: S.D. Gordon's Quiet Talks on Service is filled with riveting stories and examples explaining and supporting the idea of Christian service. Each chapter focuses on a unique side of service that applies to Christians in all walks of life. Not only does this text provide wonderful examples of application, it also supports a great framework by which all Christians can live lives of meaningful service to Christ and the Church. As always, S. D. Gordon's wise and friendly voice provides in- sight for those looking to improve their life and relationship with Christ. Luke Getz CCEL Staff Writer i Contents Title Page 1 Personal Contact with Jesus: The Beginning of Service 2 The Beginning of an Endless Friendship 2 An Ideal Biography 3 The Eyes of the Heart 4 We are Changed 5 The Outlook Changed 7 Talking with Jesus 9 Getting Somebody Else 10 The True Source of Strong Service 12 The Triple Life: The Perspective of Service 13 On An Errand for Jesus 13 The Parting Message 14 A Secret Life of Prayer 16 An Open Life of Purity 19 An Active Life of Service 22 The Perspective of True Service 24 A Long Time Coming 26 Yokefellows: The Rhythm of Service 28 The Master's Invitation 28 Surrender a Law of Life 29 Free Surrender 31 "Him" 32 Yoked Service 33 In Step with Jesus 34 The Scar-marks of Surrender 36 ii Full Power through Rhythm 38 He is Our Peace 40 The Master's Touch 41 A Passion for Winning Men: The Motive-power -

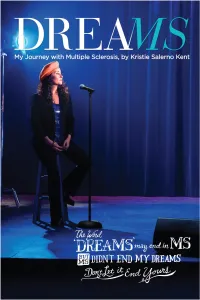

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with. -

Reggae: Jamaica's Rebel Music

74 ',1,.)ryry (n ro\ 6 o\ tz o a q o = Kingston 75 Reggqes Jomqicq's Rebel fUlusic By Rita Forest* "On the day that Bob Marley died from which this burst forth, has I was buying vegetables in the mar- been described as a "very small con- ket town of Kasr El Kebir in nor- nection that's glowing red-hot" bet- thern Morocco. Kasr El Kebir was a ween "two extremely heavy cultu- E great city with running water and res"-Africa and North America. ot streetlights when London and Paris But reggae (and its predecessors, ska were muddy villages. Moroccans and rock-steady) came sparking off U tend not to check for any form of that red-hot wire at a particular o western music, vastly preferring the moment-a time in the mid-1960s odes of the late great Om Kalthoum when Jamaica was in the throes of a or the latest pop singer from Cairo mass migration from the country- z= or Beirut. But young Moroccans side to the city. These people, driven 5 love Bob Marley, the from green a only form of the hills into the hellish Ut non-Arabic music I ever saw country tangle of Kingston shantytowns, d= Moroccans willingly dance to. That created reggae music. afternoon in Kasr El Kebir, Bob This same jolting disruption of a Marley banners in Arabic were centuries-old way of life has also strung across the main street. ." shaped the existence of many mil- (Stephen Davis, Reggoe Internatio- lions of people in cities around the nal, 1982). -

William B. Evans Appointed Police Commissioner of The

VOL. 118 - NO. 3 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, JANUARY 17, 2014 $.30 A COPY William B. Evans Appointed Police Commissioner of the Boston Police Department William Gross Named Superintendent in Chief root causes of violence and agement team as Superin- Department. As a Patrol make sure everyone feels tendent of the Bureau of Officer he spent many years safe in our city,” said Mayor Field Services. Commis- in the Gang Unit and Drug Walsh. “He understands that sioner Evans is a 2008 Control Unit, as well as serv- we can’t just react to crime graduate of Harvard Univer- ing as an Academy Instruc- — we must work together to sity, John F. Kennedy School tor. He rose through the prevent it from happening in of Government and recently ranks, achieving the ranks the first place.” completed a certificate pro- of Sergeant and Sergeant Commissioner Evans is a gram for Senior Executives Detective and was promoted 33-year veteran of the Bos- in State and Local Govern- to Deputy Superintendent in ton Police Department and ment and participated in 2008, where he became a has held leadership roles the National Preparedness member of the Command within the Department for Leadership Initiative, John Staff of the Department. As several years. Evans has F. Kennedy School of Gov- Deputy Superintendent, had notable roles in the suc- ernment/Harvard School of Gross served as the Com- cessful, peaceful handling Public Health as well as mander of Zone 2, which Superintendent in Chief Boston Police Commissioner of the 70-day occupation of National Post-Graduate is comprised of Area B-2 of the Boston Police WILLIAM B. -

Canadian Women Poets and Poetic Identity : a Study of Marjorie

CANADIAN WOMEN POETS AND POETIC IDENTITY: A STUDY OF MARJORIE PICKTHALL, CONSTANCE LINDSAY SKINNER, AND THE EARLY WORK OF DOROTHY LIVESAY Diana M.A. Relke B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1982 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English 0 Diana M.A. Relke 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy, or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name : Diana M.A. Relke Degree : Doctor of Philosophy Title of Dissertation: Canadian Women Poets and Poetic Identity: A Study of Marjorie Pickthall, Constance Lindsay Skinner, and the Early Work of Dorothy Livesay. Examining Committee: Chairperson: Chinmoy Banerjee Sandra,,Djwa, Professor, Wnior Supervisor -------a-=--=--J-% ------- b -------- Meredith Kimball, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, S.F.U. --------------. ------------ Diana Brydon, ~ssociatklProfessor, University of British Columbia Date Approved : ii Canadian Women Poets and Poetic Identity: A Study of Marjorie Pickthall , Constance Lindsay Skinner, and the Early Work of -_______^_ -- ----.^ . _ -.___ __ Dorothy Livesay. ---- ---..--- .-------- -.---.----- --- ---- Diana M.A. Re1 ke --- -- ---. ----- - ---* - -.A -- Abstract This study is an examination of the evolution of the female tradition during the transitional period from 1910 to 1932 which signalled the beginning of modern Canadian poetry. Selective and analytical rather than comprehensive and descriptive, it focuses on three representative poets of the period and traces the development of the female poetic self-concept as it is manifested in their work. Critical concepts are drawn from several feminist theories of poetic identity which are based on the broad premise that poetic identity is a function of cultural experience in general and literary experience in particular.