Southeast Asia Going Digital: Connecting Smes, OECD, Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobifone Apn Settings Android

Mobifone apn settings android Continue South Africa Cell C South Africa (Cell C Coverage Map) Service: Internet APN: Internet User Name: Password: Service: MMS APN: mms User name: Password: Wap Gateway: 196.031.116.250 Port: 8080 MMS Center: MTN South Africa (MTN Coverage Map) Service: Internet APN: Internet User Name: Guest Password: Service: MMS APN: Internet User Name: mtnmms Password: mtnmms Wap Gateway: 196.011.240.241 Port: 8080 MMS Center: Telkom/8ta South Africa (Telkom Coverage Map) Service: Internet APN: Internet username: guest password: Guest service: MMS APN: mms username: guest password: GUEST: WAP Gateway guest: 41 .151.254.162 Port: 8080 MMSC: Vodacom South Africa (Vodacom Coverage Map) Service: Internet APN: Internet User Name: Password: Service: MMS APN: mms.vodacom.net User Name: Password: Password : WAP Gateway: 196.6.128.13 Port: 8080 MMSC : Virgin Mobile South Africa Service: Internet APN: vdata Username: Guest password: Service: MMS APN: virgin_mms username: guest password: Guest WapGateway: 196.31.116.242 MMS Center: Albania Vodafone Albania Service: Internet APN: Twa Username: Password: Argentina CTI Argentina Service: Internet APN: internet.ctimovil.com.ar Username: Guest password: Movistar Argentina Service: Internet APN: internet.gprs.unifon.com.ar Username: wap Password: Argentina Personal Service: Internet APN: gprs.personal.com User Name: Mobile Number: Australia Optus Australia Service: Internet APN: Internet User Name: Guest Password: Telstra Australia Service: Internet APN: telestra.internet User name: -

In This Issue: 11 Years All Optical Submarine Network Upgrades Of

66 n o v voice 2012 of the ISSn 1948-3031 Industry System Upgrades Edition In This Issue: 11 Years All Optical Submarine Network Upgrades of Upgrading Cables Systems? More Possibilities That You Originally Think Of! Excellence Reach, Reliability And Return On Investment: The 3R’s To Optimal Subsea Architecture Statistics Issue Issue Issue #64 Issue #3 #63 #2 Released Released Issue Released Released #65 Released 2 ISSN No. 1948-3031 PUBLISHER: Wayne Nielsen MANAGING EDITOR: Kevin G. Summers ovember in America is the month Forum brand which we will be rolling out we celebrate Thanksgiving. It during the course of the year, and which CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Stewart Ash, is also the month SubTel Forum we believe will further enhance your James Barton, Bertrand Clesca, Dr Herve Fevrier, N Stephen Jarvis, Brian Lavallée, Pete LeHardy, celebrates our anniversary of existence, utility and enjoyment. We’re going to kick Vinay Rathore, Dr. Joerg Schwartz that now being 11 years going strong. it up a level or two, and think you will like the developments . And as always, it will Submarine Telecoms Forum magazine is When Ted and I established our little be done at no cost to our readers. published bimonthly by Submarine Telecoms magazine in 2001, our hope was to get Forum, Inc., and is an independent commercial enough interest to keep it going for a We will do so with two key founding publication, serving as a freely accessible forum for professionals in industries connected while. We had a list of contacts, an AOL principles always in mind, which annually with submarine optical fiber technologies and email address and a song in our heart; the I reaffirm to you, our readers: techniques. -

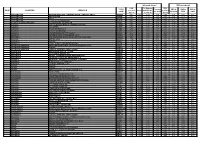

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

Aliexpress's Strategic Choice for Entering the E-Commerce Market in Thailand Yan Shijie 5917195406 an Independent Study Submitte

ALIEXPRESS'S STRATEGIC CHOICE FOR ENTERING THE E-COMMERCE MARKET IN THAILAND YAN SHIJIE 5917195406 AN INDEPENDENT STUDY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS SIAM UNIVERSITY 2018 ALIEXPRESS'S STRATEGIC CHOICE FOR ENTERING THE E-COMMERCE MARKET IN THAILAND ABSTRACT Title: Aliexpress's Strategic Choice For Entering the E-Commerce Market in Thailand By: Yan Shijie Degree: Master of Business Administration Major: Business Administration Advisor: (Associate Professor Wei Qifeng) / / In recent years, China's traditional export trade has slowed, but cross-border e-commerce has developed momentum. Cross-border e-commerce has the characteristics of shortening the trading phase and reducing costs, bypassing the traditional trade intermediary links, making it possible for producers to directly face end consumers, both to raise profits and to lower commodity prices. Because domestic e-commerce market is beginning to enter the saturated period, Chinese enterprises seek new markets abroad in order to get rid of fierce competition from the country. When an enterprise wants to gain access to foreign markets, it is necessary to analyze the country's environment and understand the local market and industry's specific circumstances. SWOT is a common strategic analysis tool. This paper mainly studies the strategy selection of China's cross-border e-commerce platform into Thailand, and is an example of Alibaba's AliExpress, which shows whether it should enter the Thai market and how it should be entered. Based on the 4M analysis, 7 'S analysis, PEST analysis and Porter's five-force model, this paper analyzes the internal and external environment, finds out the strengths and weaknesses of the platform, the opportunities and threats existing in Thailand's market and uses five points to quantify the four factors. -

SUPPLY RECORD - REPEATERED SYSTEM ( 1 ) 1St Generation (Regenerator System Using 1.31 Micron Wavelength)

SUPPLY RECORD - REPEATERED SYSTEM ( 1 ) 1st Generation (Regenerator System using 1.31 micron wavelength) System Landing Countries Capacity Route Length Delivery Japan, U.S.A. (Guam, TPC-3 (Note 1) 560Mbps (280Mbps x 2fp) 3,760km Dec. 88 Hawaii) Hong Kong, Japan, Hong Kong-Japan-Korea 560Mbps (280Mbps x 2fp) 4,700km Apr. 90 Korea Kuantan-Kota Kinabaru Malaysia 840Mbps (420Mbps x 2fp) 1,570km Dec. 90 Japan, U.S.A. North Pacific Cable (NPC) 1680Mbps (420Mbps x 4fp) 9,400km Apr. 91 (Mainland) Surabaya-Banjarmasin Indonesia 280Mbps (280Mbps x 1fp) 410km Dec. 91 N. ote 1:The very first Branching Units deployed in the Pacific 1 SUPPLY RECORD - REPEATERED SYSTEM ( 2 ) 2nd Generation (Regenerator System using 1.55 micron wavelength) System Landing Sites Capacity Route Length Delivery UK-Germany No.5 (Note 2) UK, Germany 3.6Gbps (1.8Gbps x 2fp) 500km Oct. 91 Brunei-Singapore Brunei, Singapore 1120Mbps (560Mbps x 2fp) 1500km Nov. 91 Brunei, Malaysia, Brunei-Malaysia-Philippines (BMP) 1120Mbps (560Mbps x 2fp) 1500km Jan. 92 Philippines Japan, U.S.A. TPC-4 1680Mbps (560Mbps x 3fp) 5000km Oct. 92 (Mainland) Japan, Hong Kong, APC Taiwan, Malaysia, 1680Mbps (560Mbps x 3fp) 7600km Aug. 93 Singapore Malaysia-Thailand Malaysia, Thailand 1120Mbps (560Mbps x 2fp) 1500km Aug. 94 (incl. Petchaburi-Sri Racha) Russia-Japan-Korea (RJK) Russia, Japan, Korea 1120Mbps (560Mbps x 2fp) 1700km Nov. 94 Thailand, Vietnam, Thailand-Vietnam-Hong Kong (T-V-H) 1120Mbps (560Mbps x 2fp) 3400km Nov. 95 Hong Kong N. ote 2: The very first giga bit submarine cable system in the world 2 SUPPLY RECORD - REPEATERED SYSTEM ( 3 ) 3rd Generation (Optical Amplifier System) System Landing Sites Capacity Route Length Delivery Malaysia Domestic (Southern Link) Malaysia 10Gbps (5Gbps x 2fp) 2,300km Jul. -

March Quarter 2020 and Full Fiscal Year 2020 Results

March Quarter 2020 and Full Fiscal Year 2020 Results May 22, 2020 Disclaimer This presentation contains certain financial measures that are not recognized under generally accepted accounting principles in the United States (“GAAP”), including adjusted EBITDA (including adjusted EBITDA margin), adjusted EBITA (including adjusted EBITA margin), marketplace-based core commerce adjusted EBITA, non-GAAP net income, non-GAAP diluted earnings per share/ADS and free cash flow. For a reconciliation of these non-GAAP financial measures to the most directly comparable GAAP measures, see GAAP to Adjusted/Non-GAAP Measures Reconciliation. This presentation contains forward-looking statements. These statements are made under the “safe harbor” provisions of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. These forward-looking statements can be identified by terminology such as “will,” “expects,” “anticipates,” “future,” “intends,” “plans,” “believes,” “estimates,” “potential,” “continue,” “ongoing,” “targets,” “guidance” and similar statements. Among other things, statements that are not historical facts, including statements about Alibaba’s strategies and business plans, Alibaba’s beliefs, expectations and guidance regarding the growth of its business and its revenue, the business outlook and quotations from management in this presentation, as well as Alibaba’s strategic and operational plans, are or contain forward-looking statements. Alibaba may also make forward-looking statements in its periodic reports to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”), in announcements made on the website of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Hong Kong Stock Exchange”), in press releases and other written materials and in oral statements made by its officers, directors or employees to third parties. -

Creating Trust in Critical Network Infrastructures: Korean Case Study

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION ITU WORKSHOP ON Document: CNI/05 CREATING TRUST IN CRITICAL 20 May 2002 NETWORK INFRASTRUCTURES Seoul, Republic of Korea — 20 - 22 May 2002 CREATING TRUST IN CRITICAL NETWORK INFRASTRUCTURES: KOREAN CASE STUDY Creating trust in critical network infrastructures: Korean case study This case study has been prepared by Dr. Chaeho Lim <[email protected]>. Dr Cho is Visiting Professor at the Korean Institute of Advanced Science & Technology, in the Infosec Education and Hacking, Virus Research Centre. This case study, Creating Trust in Critical Network Infrastructures: Korean Case Study, is part of a series of Telecommunication Case Studies produced under the New Initiatives programme of the Office of the Secretary General of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Other country case studies on Critical Network Infrastructures can be found at <http://www.itu.int/cni>. The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Telecommunication Union, its membership or the Korean Government. The author wishes to acknowledge Mr Chinyong Chong <[email protected]> of the Strategy and Policy Unit of ITU for contributions to the paper. The paper has been edited by the ITU secretariat. The author gratefully acknowledges the generous assistance of all those who have contributed information for this report. In particular, thanks are due to staff of Ministry of Information and Communication and Korean Information Security Agency for their help and suggestions. 2/27 Creating trust in critical network infrastructures: Korean case study TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................................. -

(2019). Bank X, the New Banks

BANK X The New New Banks Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions March 2019 Citi is one of the world’s largest financial institutions, operating in all major established and emerging markets. Across these world markets, our employees conduct an ongoing multi-disciplinary conversation – accessing information, analyzing data, developing insights, and formulating advice. As our premier thought leadership product, Citi GPS is designed to help our readers navigate the global economy’s most demanding challenges and to anticipate future themes and trends in a fast-changing and interconnected world. Citi GPS accesses the best elements of our global conversation and harvests the thought leadership of a wide range of senior professionals across our firm. This is not a research report and does not constitute advice on investments or a solicitations to buy or sell any financial instruments. For more information on Citi GPS, please visit our website at www.citi.com/citigps. Citi Authors Ronit Ghose, CFA Kaiwan Master Rahul Bajaj, CFA Global Head of Banks Global Banks Team GCC Banks Research Research +44-20-7986-4028 +44-20-7986-0241 +966-112246450 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Charles Russell Robert P Kong, CFA Yafei Tian, CFA South Africa Banks Asia Banks, Specialty Finance Hong Kong & Taiwan Banks Research & Insurance Research & Insurance Research +27-11-944-0814 +65-6657-1165 +852-2501-2743 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Judy Zhang China Banks & Brokers Research +852-2501-2798 -

KDDI Global ICT Brochure

https://global.kddi.com KDDI-Global Networks and IT Solutions Networking, Colocation, System Integration around the world BUILDING YOUR BUSINESS TOGETHER KDDI solutions are at the cutting-edge in all fields of information and communications KDDI, a Fortune Global 500 company, is one of Asia’s largest telecommunications providers, with approximately US$48 billion in annual revenue and a proven track record extending over many years and around the world. We deliver all-round services, from mobile phones to fixed-line communications, making us your one-stop solution provider for telecommunications and IT environments. The high praise and trust enjoyed by our TELEHOUSE data centers positioned around the world have kept us at the forefront of service and quality. Since our establishment in 1953, we have expanded our presence into 28 countries and 60 cities, with over 100 offices around the world supporting the success of our international customers through our high quality services. KDDI’s mobile telephone brand “au” has achieved significant market share in Japan, one of the world’s most comprehensive KDDI Quick Facts communications markets. KDDI’s relationship with over 600 carriers worldwide enables us to provide high-quality international network services in over 190 countries. Our exciting ventures, built on extensive experience, include investment in the “South-East Asia Japan 2 Cable”, which connects 11 locations in 9 countries and territories in Asia. Moreover, as the world moves toward the age of IoT and 5G, KDDI is taking steps to promote IoT business, such as connected cars, support for companies engaged in global business, and the creation of new value for our society. -

Roaming User Guide

Data Roaming Tips Singtel helps you stay seamlessly connected with data roaming overseas while avoiding bill shock from unexpected roaming charges. The information below can help you make smart data roaming decisions, allowing you to enjoy your trip with peace of mind. 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming ...................................................................................... 2 2. USA Data Roaming Plan Coverage .......................................................................................................... 13 3. Network Lock .............................................................................................................................................. 14 4. My Roaming Settings................................................................................................................................. 16 5. Data Roaming User Guide ......................................................................................................................... 16 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming The following table lists our preferred operators offering Singtel data roaming plans and indicates their handset display names. Country Roaming Plans Operator Handset Display Albania Daily Vodafone (LTE) VODAFONE AL / voda AL / AL-02 / 276-02 Anguilla Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 365 840 Antigua and Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 344 920 Barbuda CLARO Argentina / CTIARG / AR310 / Claro (LTE) Claro AR Argentina Daily Telefonica (LTE) AR 07 / 722 07 / unifon / movistar Armenia Daily VEON (LTE) -

Broadband Infrastructure in the ASEAN-9 Region

BroadbandBroadband InfrastructureInfrastructure inin thethe ASEANASEAN‐‐99 RegionRegion Markets,Markets, Infrastructure,Infrastructure, MissingMissing Links,Links, andand PolicyPolicy OptionsOptions forfor EnhancingEnhancing CrossCross‐‐BorderBorder ConnectivityConnectivity Michael Ruddy Director of International Research Terabit Consulting www.terabitconsulting.com PartPart 1:1: BackgroundBackground andand MethodologyMethodology www.terabitconsulting.com ProjectProject ScopeScope Between late‐2012 and mid‐2013, Terabit Consulting performed a detailed analysis of broadband infrastructure and markets in the 9 largest member countries of ASEAN: – Cambodia – Indonesia – Lao PDR – Malaysia – Myanmar – Philippines – Singapore – Thailand – Vietnam www.terabitconsulting.com ScopeScope (cont(cont’’d.)d.) • The data and analysis for each country included: Telecommunications market overview and analysis of competitiveness Regulation and government intervention Fixed‐line telephony market Mobile telephony market Internet and broadband market Consumer broadband pricing Evaluation of domestic network connectivity International Internet bandwidth International capacity pricing Historical and forecasted total international bandwidth Evaluation of international network connectivity including terrestrial fiber, undersea fiber, and satellite Evaluation of trans‐border network development and identification of missing links www.terabitconsulting.com SourcesSources ofof DataData • Terabit Consulting has completed dozens of demand studies for -

Alibaba Group Announces March Quarter 2018 Results and Full Fiscal Year 2018 Results

Alibaba Group Announces March Quarter 2018 Results and Full Fiscal Year 2018 Results Hangzhou, China, May 4, 2018 – Alibaba Group Holding Limited (NYSE: BABA) today announced its financial results for the quarter ended March 31, 2018 and fiscal year then ended. “Alibaba Group had an excellent quarter and fiscal year, driven by robust growth in our core commerce business and investments we have made over the past several years in longer-term growth initiatives,” said Daniel Zhang, Chief Executive Officer of Alibaba Group. “With the continuing roll out of our New Retail strategy, our e-commerce platform is developing into the leading retail infrastructure of China. During the past year we also doubled down on technology development, cloud computing, logistics, digital entertainment and local services so that we are in a position to capture consumption growth in China and other emerging markets.” “Fiscal 2018 culminated with a quarter we are very proud of. Full year revenue grew 58%, core commerce revenue grew 60%, with profit growth of over 40% and annual free cash flow of US$15.8 billion,” said Maggie Wu, Chief Financial Officer of Alibaba Group. “Looking ahead to fiscal 2019, we expect overall revenue growth above 60%, reflecting our confidence in our core business as well as positive momentum in new businesses. We expect our new growth initiatives will drive long-term, sustainable value for our customers and partners and increase our total addressable market.” BUSINESS HIGHLIGHTS In the quarter ended March 31, 2018: Revenue was RMB61,932 million (US$9,873 million), an increase of 61% year-over-year.