Have to Say It in a Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Perspective on the Presley Legend

JULY, 1986 Vol 10 No 6 ISSN 0314 - 0598 A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust A New Perspective on the Presley Legend ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT? by Alan Bleasdale Directed by Robin Lefevre Designed by Voytek Lighting designed by John Swaine Musical direction by Frank Esler-Smith Cast: Martin Shaw, David Franklin, Peta Toppano, Marcia Hines, John Derum, Lynda Stoner, Mervyn Drake, Ron Hackett and Jennifer West Her Majesty's Theatre heap of foil-wrapped Cadillac bon A nets (or is it crushed Cadillacs) form a stage upon a stage to set the mood for ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT?, Alan Bleasdale's play with songs about the life and death of Elvis Presley. On the lower stage, Gracelands, the garish pink Presley mansion with its outrageous chandeliers, is portrayed. Here, on the last day of his life, is "The King", now ageing, bloated, pill-popping and wear ing a purple jumpsuit and sunglasses. He watches his old movies and fumes because one of his trusted "aides" is ex posing his secrets to a newspaperman. In a series of flashbacks, Elvis relives his earlier experiences, the death of the twin brother whom he believes was his alter ego and stronger half, the death of his mother while he was a GI in Ger many, and the adulation poured on him as the lean, sexy king of rock. HiS manager, Colonel Tom Parker, is por trayed as his manipulator, holding a Presley dummy and gloating over the Martin Shaw as the ageing Presley in ARE profits. LONESOME TONIGHT? and (inset) as himself Author Bleasdale wrote the play to achieve a personal vindication of Presley, London critics were not always kind of $9.00 per ticket). -

Music & Film Memorabilia

MUSIC & FILM MEMORABILIA Friday 11th September at 4pm On View Thursday 10th September 10am-7pm and from 9am on the morning of the sale Catalogue web site: WWW.LSK.CO.Uk Results available online approximately one hour following the sale Buyer’s Premium charged on all lots at 20% plus VAT Live bidding available through our website (3% plus VAT surcharge applies) Your contact at the saleroom is: Glenn Pearl [email protected] 01284 748 625 Image this page: 673 Chartered Surveyors Glenn Pearl – Music & Film Memorabilia specialist 01284 748 625 Land & Estate Agents Tel: Email: [email protected] 150 YEARS est. 1869 Auctioneers & Valuers www.lsk.co.uk C The first 91 lots of the auction are from the 506 collection of Jonathan Ruffle, a British Del Amitri, a presentation gold disc for the album writer, director and producer, who has Waking Hours, with photograph of the band and made TV and radio programmes for the plaque below “Presented to Jonathan Ruffle to BBC, ITV, and Channel 4. During his time as recognise sales in the United Kingdom of more a producer of the Radio 1 show from the than 100,000 copies of the A & M album mid-1980s-90s he collected the majority of “Waking Hours” 1990”, framed and glazed, 52 x 42cm. the lots on offer here. These include rare £50-80 vinyl, acetates, and Factory Records promotional items. The majority of the 507 vinyl lots being offered for sale in Mint or Aerosmith, a presentation CD for the album Get Near-Mint condition – with some having a Grip with plaque below “Presented to Jonathan never been played. -

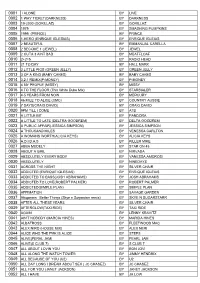

4BH 1000 Best Songs 2011 Prez Final

The 882 4BH1000BestSongsOfAlltimeCountdown(2011) Number Title Artist 1000 TakeALetterMaria RBGreaves 999 It'sMyParty LesleyGore 998 I'llNeverFallInLoveAgain BobbieGentry 997 HeavenKnows RickPrice 996 ISayALittlePrayer ArethaFranklin 995 IWannaWakeUpWithYou BorisGardiner 994 NiceToBeWithYou Gallery 993 Pasadena JohnPaulYoung 992 IfIWereACarpenter FourTops 991 CouldYouEverLoveMeAgain Gary&Dave 990 Classic AdrianGurvitz 989 ICanDreamAboutYou DanHartman 988 DifferentDrum StonePoneys/LindaRonstadt 987 ItNeverRainsInSouthernCalifornia AlbertHammond 986 Moviestar Harpo 985 BornToTry DeltaGoodrem 984 Rockin'Robin Henchmen 983 IJustWantToBeYourEverything AndyGibb 982 SpiritInTheSky NormanGreenbaum 981 WeDoIt R&JStone 980 DriftAway DobieGray 979 OrinocoFlow Enya 978 She'sLikeTheWind PatrickSwayze 977 GimmeLittleSign BrentonWood 976 ForYourEyesOnly SheenaEaston 975 WordsAreNotEnough JonEnglish 974 Perfect FairgroundAttraction 973 I'veNeverBeenToMe Charlene 972 ByeByeLove EverlyBrothers 971 YearOfTheCat AlStewart 970 IfICan'tHaveYou YvonneElliman 969 KnockOnWood AmiiStewart 968 Don'tPullYourLove Hamilton,JoeFrank&Reynolds 967 You'veGotYourTroubles Fortunes 966 Romeo'sTune SteveForbert 965 Blowin'InTheWind PeterPaul&Mary 964 Zoom FatLarry'sBand 963 TheTwist ChubbyChecker 962 KissYouAllOver Exile 961 MiracleOfLove Eurythmics 960 SongForGuy EltonJohn 959 LilyWasHere DavidAStewart/CandyDulfer 958 HoldMeClose DavidEssex 957 LadyWhat'sYourName Swanee 956 ForeverAutumn JustinHayward 955 LottaLove NicoletteLarson 954 Celebration Kool&TheGang 953 UpWhereWeBelong -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

ARIA TOP 50 JAZZ and BLUES ALBUMS CHART 2010 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 JAZZ AND BLUES ALBUMS CHART 2010 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 MICHAEL BUBLE Michael Buble <P>7 RPS/WAR 9362483762 2 IT'S TIME Michael Buble <P>5 RPS/WAR 9362489462 3 CALL ME IRRESPONSIBLE Michael Buble <P>5 RPS/WAR 9362499987 4 MELINDA DOES DORIS Melinda Schneider UMA 2747553 5 COME AWAY WITH ME Norah Jones <P>10 EMI 5417472 6 THE FALL Norah Jones <G> BNO/EMI 4569662 7 MARCIA SINGS TAPESTRY Marcia Hines UMA 2751916 8 MY ONE AND ONLY THRILL Melody Gardot UCJ/UMA 1796782 9 THE VERY BEST OF DIANA KRALL Diana Krall VE/UMA 1739968 10 FLY ME TO THE MOON Various ABC/UMA 5331377 11 BABY ITS COLD OUTSIDE VOL 2 Various ABC/UMA 5326857 12 SONGS THAT WON THE WAR Various ACL/UMA 4763808 13 QUIET NIGHTS Diana Krall <G> VE/UMA 1793110 14 SOME LIKE IT HOT Various Artists ABC/UMA 5323351 15 FEELS LIKE SPRING James Morrison & The Idea Of North ACL/UMA 2735660 16 SOMETIMES THE STARS The Audreys ABC/UMA 2751424 17 A CHRISTMAS CORNUCOPIA Annie Lennox ISL/UMA 2753309 18 THE IMAGINE PROJECT Herbie Hancock SME 88697748612 19 THE PURSUIT Jamie Cullum DEC/UMA 2713302 20 NOT TOO LATE Norah Jones <P> BNO/EMI 3862192 21 CIAO BELLA Alfredo Malabello SBS/UMA 2735574 22 I LEARNED THE HARD WAY Sharon Jones And The Dap-Kings CTX/SHK DAP019 23 BABY IT'S COLD OUTSIDE: SMOOTH JAZZ FOR A COZY EV… Various <G> ABC/UMA 5318789 24 BARE BONES Madeleine Peyroux UMA 6132722 25 WORRISOME HEART Melody Gardot UCJ/UMA 1749640 26 ...FEATURING Norah Jones BNO/EMI 9098682 -

Annual Report 2014 Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Ltd – Abn 102 451 785 Season Highlights 2014 Let Your Colours Burst!

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 SYDNEY GAY AND LESBIAN MARDI GRAS LTD – ABN 102 451 785 SEASON HIGHLIGHTS 2014 LET YOUR COLOURS BURST! BROADCAST PARTNER HOLDING HANDS FOR ANZ ENGAGED AS FIRST PARADE: A PLATFORM FOR TELEVISION SBS SOCHI AT FAIR DAY PRINCIPAL PARTNER COMMUNITY EXPRESSION Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Solidarity with our Russian Long-time supporter of Mardi Gras, Political statements and satire were proudly partnered with SBS2 to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, ANZ, became SGLMG’s first Principal front and centre in the Parade, with present the broadcast of the 2015 queer and intersex communities Partner, increasing its investment Ethel Yarwood’s Operation Border Parade. The broadcast featured was a recurring theme this year and support of the organisation. ANZ Security: Turn Back the Floats highlights of the Parade and content across the Festival, beginning with have made a commitment of three setting the tone. Solidarity with captured throughout the Festival a spectacular gesture at Fair Day. years, taking the partnership into its LGBTQI Russians was prominent and was shown on television the Tens of thousands of people joined 10th year in 2016. In its first year as with Putin on the Ritz, To Russia Sunday night following the Parade. hands to show support for Russian Principal Partner, ANZ hosted the With Love, and Putin the Heartless LGBTQI people, to coincide with the festival program launch, produced a featuring a giant puppet Putin. There SBS2 also presented the broadcast Opening Ceremony of the Winter Parade float and created GAYTMs, was a visible Intersex presence in as video on demand content and Olympics in Sochi. -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE FREE VOL. II NO. 1 YOU'LL NEVER GET RICH READING THE PITCH FEBRUARY 1981 FBIIRUARY II The 8-52'5 Meet BUDGBT The Rev. in N.Y. Third World Bit List .ONTHI l ·TRIVIA QUIZ· WHAT? SQt·1E RECORD PRICES ARE ACTUALLY ~~nll .815 m wi. i .••lIIi .... lllallle,~<M0,~ CGt4J~G ·DOWN·?····· S€f ·PAGE: 3. FOR DH AI LS , prizes PAGE 2 THE PENNY PITCH LETTERS Dec. 29,1980 Dear Warren, Over the years, Kansas Attorney General's have done many strange things. Now the Kansas Attorney General wants to stamp out "Mumbo Jumbo." 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Does this mean the "Immoral Minority" (816) 561·1580 will be banned from Kansas? Is being banned from Kansas a hardship? Edi tor ....••..•••.• vifarren Stylus Morris Martin Contributing vlriters this issue: Raytown, Mo. P.S. He probably doesn't like dreadlocks Rev. Dwight Frizzell, Lane & Dave from either. GENCO labs, Blind Teddy Dibble, I-Sheryl, Ie-Roths, Lonesum Chuck, Mr.D-Conn, Le Roi, Rage n i-Rick, P. Minkin, Lindsay Shannon, Mr. P. Keenan, G. Trimble, Jan. 26, 1981 debranderson, M. Olson Dear Editor, Inspiration this issue: How come K. C. radio stations never Fred de Cordova play, The Inmates "I thought I heard a Heartbeat", Roy Buchanan "Dr. Rock & Roll" Peter Green, "Loser Two Times", Marianne r,------:=~--~-__l "I don' t care what they say about Faithfull, "Broken English", etc, etc,? being avant garde or anything else. How come? Frankly, call me square if you want Is this a plot against the "Immoral to. -

December 9, 1977 No

MAC. > Vol. LV James Madison University Friday, December 9, 1977 No. 26 Spaces designated in X lot for commuter parking By MARK DAY1SON commuter student committee The proposal was passed Commuters were given 199 chairman. unanimously by the parking parking spaces, some of which "G" is the designation committee, according to Dr. are in the campus end of X lot, given to the Godwin parking John Mundy, vice president on a "trial basis" beginning lot, which is used only by for academic affairs, and next semester. commuters. chairman of the parking The proposal, made by the The proposal for commuter advisory committee. commuter student committee, parking spaces was presented was passed by the Parking to the parking committee on Criticism voiced Advisory Committee Monday. Nov. 15, and was based on a The spaces designated for report prepared by a com- commuter use are "the first muter task force which three lanes in X lot and the 21 sh-died the X lot parking by residents spaces in the small lot just patterns. south of the main X lot, as well At the parking committee as the 13 spaces along the road meeting on Dec. 5, commuters on proposal through X lot." and members_of thelnter Hall Also, "the road behind the Council met to discuss the By MARK DAVISON N-complex dorms and the proposal. Many N-complex dorm JMU'S TYRONE SHOULDERS (ID fights for a rebound against spaces along the road to the —Council President Gary senators have received VMI's center Dave Montgomery (45). Shoulders lost this fight tunnel under 1-81" will be Hallowell and senators from negative feedback concerning and the Dukes lost the game to the Keydets 86-68 in the Pit at redes ignated "G"parking. -

"Weird Al" Yankovic

"Weird Al" Yankovic - Ebay Abba - Take A Chance On Me `M` - Pop Muzik Abba - The Name Of The Game 10cc - The Things We Do For Love Abba - The Winner Takes It All 10cc - Wall Street Shuffle Abba - Waterloo 1927 - Compulsory Hero ABC - Poison Arrow 1927 - If I Could ABC - When Smokey Sings 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Long Way To The Top 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Thunderstruck 30h!3 - Don't Trust Me Ac Dc - You Shook Me All Night Long 3Oh!3 feat. Katy Perry - Starstrukk AC/DC - Rocker 5 Star - Rain Or Shine Ac/dc - Back In Black 50 Cent - Candy Shop AC/DC - For Those About To Rock 50 Cent - Just A Lil' Bit AC/DC - Heatseeker A.R. Rahman Feat. The Pussycat Dolls - Jai Ho! (You AC/DC - Hell's Bells Are My Destiny) AC/DC - Let There Be Rock Aaliyah - Try Again AC/DC - Thunderstruck Abba - Chiquitita AC-DC - It's A Long Way To The Top Abba - Dancing Queen Adam Faith - The Time Has Come Abba - Does Your Mother Know Adamski - Killer Abba - Fernando Adrian Zmed (Grease 2) - Prowlin' Abba - Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) Adventures Of Stevie V - Dirty Cash Abba - Knowing Me, Knowing You Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Abba - Mamma Mia Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator Abba - Super Trouper Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion A-Ha - Cry Wolf Alanis Morissette - Not The Doctor A-Ha - Touchy Alanis Morissette - You Oughta Know A-Ha - Hunting High & Low Alanis Morrisette - I see Right Through You A-Ha - The Sun Always Shines On TV Alarm - 68 Guns Air Supply - All Out Of Love Albert Hammond - Free Electric Band -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

14 May 1978 CHART #139 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Wuthering Heights How Deep Is Your Love Saturday Night Fever Star Wars OST 1 Kate Bush 21 Bee Gees 1 Bee Gees / Various 21 Various Last week 1 / 6 weeks EMI Last week 24 / 18 weeks PHONOGRAM Last week 1 / 7 weeks PHONOGRAM Last week 19 / 11 weeks WARNER Tania Fantasy Going Places Atlantic Crossing 2 John Rowles 22 Earth, Wind and Fire 2 Ron Goodwin / NZSO 22 Rod Stewart Last week 2 / 8 weeks EMI Last week 33 / 3 weeks CBS Last week 2 / 6 weeks EMI Last week 14 / 118 weeks WEA Night Fever Sailing The Kick Inside Footloose And Fancy Free 3 Bee Gees 23 Rod Stewart 3 Kate Bush 23 Rod Stewart Last week 8 / 2 weeks PHONOGRAM Last week 21 / 28 weeks WEA Last week 5 / 2 weeks EMI Last week 12 / 22 weeks WEA Free Me Desiree The Stranger Abba - The Album 4 Uriah Heep 24 Neil Diamond 4 Billy Joel 24 Abba Last week 3 / 10 weeks PHONOGRAM Last week 22 / 14 weeks CBS Last week 4 / 13 weeks CBS Last week 16 / 14 weeks RCA Stayin' Alive If It Don't Fit, Don't Force It Disco Magic Vol Ii I Believe In Music 5 Bee Gees 25 Kellee Patterson 5 Various 25 Perry Como Last week 4 / 11 weeks PHONOGRAM Last week 23 / 17 weeks WEA Last week 3 / 2 weeks PHONOGRAM Last week - / 1 weeks RCA It's A Heartache Take A Chance On Me Rumours Endless Flight 6 Bonnie Tyler 26 Abba 6 Fleetwood Mac 26 Leo Sayer Last week 5 / 10 weeks RCA Last week 32 / 10 weeks RCA Last week 6 / 56 weeks WEA Last week 37 / 47 weeks FESTIVAL Jack And Jill Lay Down Sally Simple Dreams Hotel California 7 Raydio 27 Eric Clapton 7 Linda Ronstadt