Conservation Area Review Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buckingham Share As at 16 July 2021

Deanery Share Statement : 2021 allocation 3AM AMERSHAM 2021 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 16-Jul-21 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4642 AMERSHAM ON THE HILL 75,869 44,973 30,896 59.3 DD S4645 AMERSHAM w COLESHILL 93,366 55,344 38,022 59.3 DD S4735 BEACONSFIELD ST MARY, MICHAEL & THOMAS 244,244 144,755 99,489 59.3 DD S4936 CHALFONT ST GILES 82,674 48,998 33,676 59.3 DD S4939 CHALFONT ST PETER 88,520 52,472 36,048 59.3 DD S4971 CHENIES & LITTLE CHALFONT 73,471 43,544 29,927 59.3 DD S4974 CHESHAM BOIS 87,147 51,654 35,493 59.3 DD S5134 DENHAM 70,048 41,515 28,533 59.3 DD S5288 FLAUNDEN 20,011 11,809 8,202 59.0 DD S5324 GERRARDS CROSS & FULMER 224,363 132,995 91,368 59.3 DD S5351 GREAT CHESHAM 239,795 142,118 97,677 59.3 DD S5629 LATIMER 17,972 7,218 10,754 40.2 DD S5970 PENN 46,370 27,487 18,883 59.3 DD S5971 PENN STREET w HOLMER GREEN 70,729 41,919 28,810 59.3 DD S6086 SEER GREEN 75,518 42,680 32,838 56.5 DD S6391 TYLERS GREEN 41,428 24,561 16,867 59.3 DD S6694 AMERSHAM DEANERY 5,976 5,976 0 0.0 Deanery Totals 1,557,501 920,018 637,483 59.1 R:\Store\Finance\FINANCE\2021\Share 2021\Share 2021Bucks Share20/07/202112:20 Deanery Share Statement : 2021 allocation 3AY AYLESBURY 2021 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 16-Jul-21 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4675 ASHENDON 5,108 2,975 2,133 58.2 DD S4693 ASTON SANDFORD 6,305 6,305 0 100.0 S4698 AYLESBURY ST MARY 49,527 23,000 26,527 46.4 S4699 AYLESBURY QUARRENDON ST PETER 7,711 4,492 3,219 58.3 DD S4700 AYLESBURY BIERTON 23,305 13,575 9,730 58.2 DD S4701 AYLESBURY HULCOTT ALL SAINTS -

Milton Keynes Neighbourhood Regeneration Phase 2 Consultation

Milton Keynes Neighbourhood Regeneration Phase 2 Consultation 11th January – 9th April 2010 www.miltonkeynes.gov.uk/regeneration Responses should be sent to: Regeneration Team, Milton Keynes Council, Civic Offices, 1 Saxon Gate East, Central Milton Keynes, MK9 3HN or email: [email protected] Deepening Divide 2 Neighbourhood Regeneration Strategy The approach is driven by the view that services will be improved and communities strengthened only where there is effective engagement and empowerment of the community 3 1 Neighbourhood Regeneration Strategy Physical Economic • Local spatial strategy that will improve the • Local employment strategy physical capital of the area • Support local business and retail provision • Improved green spaces • Promote social enterprise • Improved housing condition • Improved and increased use of facilities Social Human • Local community development and capacity • Promote healthy living and physical exercise building • Develop stronger local learning cultures • Engage ‘hard to reach’ groups • Produce local learning plans • Support building of community pride • Improved performance at school 4 Priority Neighbourhoods Within the 15% most deprived in England as defined by the IMD • Fullers Slade • Water Eaton • Leadenhall • Beanhill • Netherfield • Tinkers Bridge • Coffee Hall Within the 15-20% most deprived in England as defined by the IMD • Stacey Bushes • Bradville/New Bradwell and Stantonbury • Conniburrow • Fishermead • Springfield • Eaglestone Within the 20-25% most deprived in England -

Olney Town Council

OLNEY TOWN COUNCIL To all members of Olney Town Council You are hereby summoned to attend the Meeting of Olney Town Council to be held in The Olney Centre, on Monday 04 March 2019 at 7.30 p.m. for the purpose of transacting the following business. Liam Costello Town Clerk 27 February 2019 There will be a 15 minute open forum at the beginning of the meeting when members of the public resident in Olney are invited to address the Council. Each individual will be limited to speak for no more than 3 minutes AGENDA 1. Apologies for absence 2. Declarations of interests on items on the agenda 3. To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 14 January 2019 4. To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 04 February 2019 5. Report of meeting with Barclays on 1st March 6. Consultation on the proposal to close Emberton School 7. Near Town Gardens - Proposed Parking and Waiting Restrictions 8. Sponsorship of Hanging Baskets 9. Library request for funding for towards the Summer Reading Challenge 10. Events a. Riverfest - weekend of 6th and 7th July b. BOFF – Weekend of 14 and 15 September 11. Communications Policies a. Communications Policy Town Clerk: Mr. Liam Costello Tel: 01234 711679 e: [email protected] – Web: www.olneytowncouncil.gov.uk b. Social Media Policy 12. To receive minutes, or reports from chairman, of committees that have met since the last council meeting: a. Planning – 11 February b. Olney Development Group – 25 February 13. Interim Internal Audit Report 2018/19 14. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire Report to the Secretary of State for Transport, Local Government and the Regions August 2001 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2001 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report no: 255 ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND? v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 3 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 7 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 9 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 11 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 33 APPENDIX A Final Recommendations for Milton Keynes: Detailed Mapping 35 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for the new town of Milton Keynes and Bletchley is inserted inside the back cover of the report. LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND? The Local Government Commission for England is an independent body set up by Parliament. Our task is to review and make recommendations to the Government on whether there should be changes to local authorities’ electoral arrangements. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) We are required by law to review the electoral arrangements of every principal local authority in England. -

Decision Codes

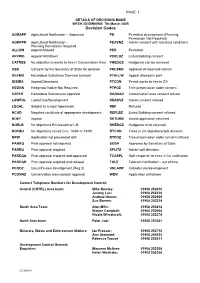

PAGE: 1 DETAILS OF DECISIONS MADE WEEK BEGINNING 7th March 2005 Decision Codes AGRAPP Agricultural Notification – Approved PD Permitted development (Planning Permission Not Required) AGRPPR Agricultural Notification – PEAVNZ Advert consent with standard conditions Planning Permission Required ALLOW Appeal Allowed PER Permitted APPWD Appeal Withdrawn PERLBZ Listed Building consent CATREE No objection to works to tree in Conservation Area PHEDGZ Hedgerow can be removed CSS Called in by the Secretary of State for decision PRESMZ Approval of reserved matters DEEMD Hazardous Substance Deemed Consent PTALLW Appeal allowed in part DISMIS Appeal Dismissed PTCON Permit works to tree in CA HEDGN Hedgerow Notice Not Required PTPOZ Tree preservation order consent HZPER Hazardous Substances Approval RCONAZ Conservation area consent refusal LAWFUL Lawful Use/Development READVZ Advert consent refused LEGAL Subject to a legal Agreement REF Refused NCAD Negative certificate of appropriate development REFLBZ Listed Building consent refused NDET Appeal RETURN Invalid application returned NOELB No objections Ecclesiastical L.B RHEDGZ Hedgerow to be retained NOOBJ No objections raised Circ. 18/84 or 14/90 RTCON Trees in CA objections/split decision NPW Application not proceeded with RTPOZ Tree preservation order consent refused PANRQ Prior approval not required SOSA Approved by Secretary of State PAREQ Prior approval required SPLITZ Advert split decision PAREQA Prior approval required and approved TCASPL Split response to trees in CA notification PAREQR Prior -

Emberton Parish Council Minutes of Meeting – Tuesday 1St October 2019

77 Emberton Parish Council st Minutes of Meeting – Tuesday 1 October 2019 Present: Councillor Victoria McLean (Chairman) Councillor Stephen Gibson (Vice Chairman) Councillor Paul Flowers Councillor Soo Hall Councillor Mike Horton Councillor Harry White Ward Councillor David Hosking (part meeting) Mr D Cobbold – resident (part meeting) Mr R Laval – Chairman – Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group (part meeting) Mr A McGrandle – resident (part meeting) Mr N Sibbald – Chair of Finance, Staff & Premises Committee, Village School Federation (part meeting) Mr S Sims, Strategic Lead, Education Access MKC (part meeting) Ms M Younger – Deputy of School Federation (part meeting) Mrs Karen Goss – Clerk and RFO Apologies for Absence - Apologies for Absence were received from Cllr Logsdail and Ward Cllrs Peter Geary and Keith McLean. Declarations of Interest in items on the Agenda – There were no Declarations of Interest. 1. MINUTES OF THE MEETING held on 3rd September 2019. These were confirmed and signed by the Chairman. 3.85 Emberton School – Mr Sims stated that the consultation was open until 3rd October for people to put forward their comments on the proposal to close Emberton School. The proposal was based on low pupil numbers over the last few years with no pupils on roll at the present time. The birth rate had dropped significantly across the borough and the position was that there were a lot of school places giving parents a choice. The consultation finishes on the 3rd October and would go to a delegated decision and taken by Councillor Nolan in November. A number of consultations had already been undertaken and MKC have been collecting information back from consultations and took it back to delegated decision as to whether to proceed to the present stage. -

Milton Keynes Councillors

LIST OF CONSULTEES A copy of the Draft Telecommunications Systems Policy document was forwarded to each of the following: MILTON KEYNES COUNCILLORS Paul Bartlett (Stony Stratford) Jan Lloyd (Eaton Manor) Brian Barton (Bradwell) Nigel Long (Woughton) Kenneth Beeley (Fenny Stratford) Graham Mabbutt (Olney) Robert Benning (Linford North) Douglas McCall (Newport Pagnell Roger Bristow (Furzton) South) Stuart Burke (Emerson Valley) Norman Miles (Wolverton) Stephen Clark (Olney) John Monk (Linford South) Martin Clarke (Bradwell) Brian Morsley (Stantonbury) George Conchie (Loughton Park) Derek Newcombe (Walton Park) Stephen Coventry (Woughton) Ian Nuttall (Walton Park) Paul Day (Wolverton) Michael O’Sullivan (Loughton Park) Reginald Edwards (Eaton Manor) Michael Pendry (Stony Stratford) John Ellis (Ouse Valley) Alan Pugh (Linford North) John Fairweather (Campbell Park) Christopher Pym (Walton Park) Brian Gibbs (Loughton Park) Hilary Saunders (Wolverton) Grant Gillingham (Fenny Stratford) Patricia Seymour (Sherington) Bruce Hardwick (Newport Pagnell Valerie Squires (Whaddon) North) Paul Stanyer (Furzton) William Harnett (Denbigh) Wedgwood Swepston (Emerson Euan Henderson (Newport Pagnell Valley) North) Cec Tallack (Campbell Park) Irene Henderson (Newport Pagnell Bert Tapp (Hanslope Park) South) Christine Tilley (Linford South) David Hopkins (Danesborough) Camilla Turnbull (Whaddon) Janet Irons (Bradwell Abbey) Paul White (Danesborough) Harry Kilkenny (Stantonbury) Isobel Wilson (Campbell Park) Michael Legg (Denbigh) Kevin Wilson (Woughton) David -

Brochure Template

MEDIA PACK 2020 Two quality, glossy monthly magazines Ensuring your brand is seen by the right people at the right time www.pulsemagazine.co.uk | 01908 465488 Connect with your target audience online and in print We produce two magazines with a combined readership of 162,000 ABOUT PULSE MAGAZINE In 2009 our first publication,MK Pulse launched with a circulation of 10,000. Today there are now two publications - MK and NN They use the Magazine to find trusted suppliers Pulse. MK Pulse is delivered throughout Milton and tradesmen and since the editorial content Keynes and Buckinghamshire and NN Pulse spans the entire month, Pulse Magazine is kept Northamptonshire. We pride ourself on carefully and referred to time and time again. selecting the 54,000 plus ABc1 areas we cover Pulse Magazine carries around 60% editorial and across both counties. advertising is interspersed among local stories, A vibrant lifestyle magazine and a trusted news, features and other information that matters companion to those living locally, Pulse Magazine to readers. Advertising is seen as an integral part is A4 in size, full colour and printed on premium of Pulse Magazine; readers value it and consume glossy paper that invites the reader and the content with interest. Advertisements are encourages retention. At home, at work and on the screened looking for items that interest, intrigue, go, people look to Pulse Magazine when they’re catch the eye, entertain and inform. When you open to discovering what’s going on in the local create well-targeted adverts that speak to readers, area. -

Key Decision No Listed on Forward Plan No Within Policy Yes Policy Document Milton Keynes Core Strategy

ITEM 6 LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK ADVISORY GROUP 8 JULY 2009 Key Decision No Listed on Forward Plan No Within Policy Yes Policy Document Milton Keynes Core Strategy STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT- UPDATE Accountable Cabinet Member: Councillor Galloway Contact Officer: Mark Harris, Senior Planning Officer Bob Wilson, Development Plans Manager 1. Purpose 1.1 This report recaps the purpose of the Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA), which was previously introduced at the Local Development Framework (LDF) Advisory Group meeting in December 2008. 1.2 The report also outlines the key findings from the draft SHLAA and sets out the how the assessment fits into the work on the Core Strategy and future LDF documents. 2. Recommendations 2.1 a) That the findings of the draft SHLAA report are noted. b) That arrangements for the documents publication are noted. 3. Issues The requirement for and purpose of the SHLAA 3.1 Every Local Authority needs to undertake a SHLAA as a key piece of technical evidence underpinning work on the LDF. The SHLAA is required to look at the supply of suitable deliverable and developable housing sites across the whole of the borough, irrespective of where Local Authorities or local communities feel development should take place. 3.2 The requirement to undertake a SHLAA is set out in Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing, and there is Practice Guidance Document, published by the (59) ITEM 6 Department for Communities and Local Government, which sets out the standard methodology for undertaking a SHLAA. The recent review of Planning Delivery Grant allocations now also provides financial incentives for having a SHLAA in place each year. -

Admissions Policy 2021

OLNEY MIDDLE SCHOOL ADMISSIONS POLICY – SEPTEMBER 2021 SCHOOL ROLL There are currently 395 on the school roll as at 1st November 2019 Roll Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Total Boys 54 55 37 56 202 Girls 45 40 55 53 193 TOTAL 99 95 92 109 395 Admissions Policy Admission Arrangements for September 2021 ● The Local Authority (LA) Admissions Team notifies parents of children in Year 2 in infant schools of the date and time of the junior school open evenings for prospective parents. These are typically held towards the end of the autumn term in agreement with the Local Authority Admission Team. ● The LA Admissions Team provides parents with details of their allocated school. ● The LA Admissions Team provides parents with a common application form and a deadline for submission. ● Priority will not be given to parents based on the date order the applications were received before the deadline. For families that subsequently move into the school’s catchment area there is no guarantee of the offer of a place. ● The Governors will consider applications based on Olney Middle as the parents ‘equal preference school’ on the LA Admissions Team return. ● Parents will be invited to an open evening in the summer term to confirm admission and to be appraised of the school’s transfer and transition arrangements. Any significant changes to the school prospectus will be made available. ● A waiting list will be maintained until October 31st (after September 1st) of the year of admission Application will be refused if a family has submitted an incorrect address on the application form. -

Item 1 Delegated Decision 28 May 2019 Proposed Closure

Wards Affected: ITEM 1 Olney DELEGATED DECISION 28 MAY 2019 PROPOSED CLOSURE OF EMBERTON SCHOOL Responsible Cabinet Member: Councillor Nolan, Cabinet Member for Children and Families Report Sponsor: Mac Heath, Director of Children’s Services Author and contact: Simon Sims, Strategic Lead, Sufficiency and Access, Tel 01908 253919 Executive Summary: In order to propose closing a maintained school the council must follow a process prescribed by law. This process is in five stages: 1) Pre-publication consultation 2) Publication of the statutory notice and proposal 3) Representation period (four weeks) 4) Decision 5) Implementation (if appropriate) There is no prescribed timeframe for a pre-publication consultation but it is recommended to last a minimum of six weeks. Schools and the council should consult with interested parties about the proposed closure. Between 21 January 2019 and 17 March 2019, the council carried out a pre-publication consultation in relation to the proposal to close Emberton School, including drop in sessions open to interested parties. This paper reports the results of the pre-publication consultation and recommends that the council proceeds to the second stage of the statutory process. 1. Recommendation(s) 1.1 That a statutory notice and proposal to close Emberton School be published. 2. Issues 2.1 Emberton School is a community infant school with an admission number of 12 in each of its three year groups. It is therefore able to accommodate up to 36 children. The catchment area of the school is Emberton, Filgrave, Petsoe and Tyringham. Children attending Emberton School in Year 2 usually transfer to Olney Middle School. -

Newport Pagnell Modified Neighbourhood Plan The

NEWPORT PAGNELL MODIFIED NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN THE CONSULTATION STATEMENT This document provides details of all the various forms of consultation that have fed into the modification of the Newport Pagnell Neighbourhood Plan. 1. THE STEERING GROUP The Steering Group, otherwise known as the Neighbourhood Plan Implementation Group (NPIG), consists of voting members, these being seven Town Councillors (Cllrs Phil Winsor - Chairman, Ian Carman, Euan Henderson, Diane Kitchen, Richard Pearson, Joan Sidebottom and Steve Urwin), a non-voting member (Alan Mills - retired senior planning officer), the Town Clerk (Shar Roselman) and the Deputy Clerk (Patrick Donovan). 2. SIX WEEKS CONSULTATION WITH STATUTORY AND OTHER CONSULTEES At the time of the pre-submission consultation, Newport Pagnell Town Council and the steering group wrote letters and/or emailed the following consultees, formally opening the consultation and advising them of the Town Council’s website address where the consultation documents could be read, and inviting comments: 2.1 Landowners, interested developers and agents 2.2 Milton Keynes Council Planning 2.3 Milton Keynes Council Highways 2.4 Milton Keynes Council Schools Liaison Team 2.5 Milton Keynes Council Infrastructure Coordination & Delivery Team 2.6 Milton Keynes Council Planning Obligations & Tariffs 2.7 NHS Milton Keynes Clinical Commissioning Group 2.8 Hertfordshire & South Midlands Area Team of NHS England 2.9 Ward Councillors of Unitary Authority representing the area 2.10 The Newport Pagnell Business Association 2.11 The Newport Pagnell Partnership 2.12 Milton Keynes Chamber of Commerce 2.13 Neighbouring Parish Councils 2.14 Central Beds Council 2.15 Housing Associations in the area 2.16 Affected Utility Companies and water and sewerage organisations.