Mileva Einsteinmarić

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0045-Flyer-Einstein-En-2.Pdf

FEATHERBEDDINGCOMPANYWEIN HOFJEREMIAHSTATUESYN AGOGEDREYFUSSMOOSCEMETERY MÜNSTERPLATZRELATIVI TYE=MC 2NOBELPRIZEHOMELAND PERSECUTIONAFFIDAVIT OFSUPPORTEMIGRATIONEINSTEIN STRASSELETTERSHOLOCAUSTRESCUE FAMILYGRANDMOTHERGRANDFAT HERBUCHAUPRINCETONBAHNHOF STRASSE20VOLKSHOCHSCHULEFOU NTAINGENIUSHUMANIST 01 Albert Einstein 6 7 Albert Einstein. More than just a name. Physicist. Genius. Science pop star. Philosopher and humanist. Thinker and guru. On a par with Copernicus, Galileo or Newton. And: Albert Einstein – from Ulm! The most famous scientist of our time was actually born on 14th March 1879 at Bahnhofstraße 20 in Ulm. Albert Einstein only lived in the city on the Danube for 15 months. His extended family – 18 of Einstein’s cousins lived in Ulm at one time or another – were a respected and deep-rooted part of the city’s society, however. This may explain Einstein’s enduring connection to the city of his birth, which he described as follows in a letter to the Ulmer Abend- post on 18th March 1929, shortly after his 50th birthday: “The birthplace is as much a unique part of your life as the ancestry of your biological mother. We owe part of our very being to our city of birth. So I look on Ulm with gratitude, as it combines noble artistic tradition with simple and healthy character.” 8 9 The “miracle year” 1905 – Einstein becomes the founder of the modern scientific world view Was Einstein a “physicist of the century”? There‘s no doubt of that. In his “miracle year” (annus mirabilis) of 1905 he pub- lished 4 groundbreaking works along- side his dissertation. Each of these was worthy of a Nobel Prize and turned him into a physicist of international standing: the theory of special relativity, the light quanta hypothesis (“photoelectric effect”), Thus, Albert Einstein became the found- for which he received the Nobel Prize in er of the modern scientific world view. -

Berlin Period Reports on Albert Einstein's Einstein's FBI File –

Appendix Einstein’s FBI file – reports on Albert Einstein’s Berlin period 322 Appendix German archives are not the only place where Einstein dossiers can be found. Leaving aside other countries, at least one personal dossier exists in the USA: the Einstein File of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).1036 This file holds 1,427 pages. In our context the numerous reports about Ein- stein’s “Berlin period” are of particular interest. Taking a closer look at them does not lead us beyond the scope of this book. On the contrary, these reports give a complex picture of Einstein’s political activities during his Berlin period – albeit from a very specific point of view: the view of the American CIC (Counter Intelligence Corps) and the FBI of the first half of the 1950s. The core of these reports is the allegation that Einstein had cooperated with the communists and that his address (or “office”) had been used from 1929 to 1932 as a relay point for messages by the CPG (Communist Party of Germany, KPD), the Communist International and the Soviet Secret Service. The ultimate aim of these investigations was, reportedly, to revoke Einstein’s United States citizenship and banish him. Space constraints prevent a complete review of the individual reports here. Sounderthegivencircumstancesasurveyofthecontentsofthetwomost im- portant reports will have to suffice for our purposes along with some additional information. These reports are dated 13 March 1950 and 25 January 1951. 13 March 1950 The first comprehensive report by the CIC (Hq. 66th CIC Detachment)1037 about Einstein’s complicity in activities by the CPG and the Soviet Secret Service be- tween 1929 and 1932 is dated 13 March 1950.1038 Army General Staff only submit- ted this letter to the FBI on 7 September 1950. -

The Collaboration of Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein

Asian Journal of Physics Vol 24, No 4 (2015) March The collaboration of Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein Estelle Asmodelle University of Central Lancashire School of Computing, Engineering and Physical Sciences, Preston, Lancashire, UK PR1 2HE. e-mail: [email protected]; Phone: +61 418 676 586. _____________________________________________________________________________________ This is a contemporary review of the involvement of Mileva Marić, Albert Einstein’s first wife, in his theoretical work between the period of 1900 to 1905. Separate biographies are outlined for both Mileva and Einstein, prior to their attendance at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zürich in 1896. Then, a combined journal is described, detailing significant events. In additional to a biographical sketch, comments by various authors are compared and contrasted concerning two narratives: firstly, the sequence of events that happened and the couple’s relationship at particular times. Secondly, the contents of letters from both Einstein and Mileva. Some interpretations of the usage of pronouns in those letters during 1899 and 1905 are re-examined, and a different hypothesis regarding the usage of those pronouns is introduced. Various papers are examined and the content of each subsequent paper is compared to the work that Mileva was performing. With a different take, this treatment further suggests that the couple continued to work together much longer than other authors have indicated. We also evaluate critics and supporters of the hypothesis that Mileva was involved in Einstein’s work, and refocus this within a historical context, in terms of women in science in the late 19th century. Finally, the definition of, collaboration (co-authorship, specifically) is outlined. -

Albert Einstein - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 27

Albert Einstein - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 27 Albert Einstein From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Albert Einstein ( /ælbərt a nsta n/; Albert Einstein German: [albt a nʃta n] ( listen); 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics.[2] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect". [3] The latter was pivotal in establishing quantum theory within physics. Near the beginning of his career, Einstein thought that Newtonian mechanics was no longer enough to reconcile the laws of classical mechanics with the laws of the electromagnetic field. This led to the development of his special theory of relativity. He Albert Einstein in 1921 realized, however, that the principle of relativity could also be extended to gravitational fields, and with his Born 14 March 1879 subsequent theory of gravitation in 1916, he published Ulm, Kingdom of Württemberg, a paper on the general theory of relativity. He German Empire continued to deal with problems of statistical Died mechanics and quantum theory, which led to his 18 April 1955 (aged 76) explanations of particle theory and the motion of Princeton, New Jersey, United States molecules. He also investigated the thermal properties Residence Germany, Italy, Switzerland, United of light which laid the foundation of the photon theory States of light. In 1917, Einstein applied the general theory of relativity to model the structure of the universe as a Ethnicity Jewish [4] whole. -

Einstein and Besso: from Zürich to Milano

1 Einstein and Besso: From Zürich to Milano. Christian BRACCO Syrte, CNRS-Observatoire de Paris, 61, avenue de l’observatoire, 75014 Paris CRHI, EA 4318, Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, UFR LASH, BP 3209, 98 Bd Hériot, 06204 Nice Cedex 3. E-mail : [email protected] Presented at the Istituto Lombardo, Accademia di Scienze e Lettere, Milan, Italy. Session of Thursday 18th December 2014. To be published in the Rendiconti for year 2014. Abstract: The 1896-1901 Milanese period is a key one to understand Einstein’s training background. When he was a student at the ETH in Zürich (the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zürich) from 1896 to 1900, he would make regular trips back to Milan to stay with his family who was involved in the development of the electricity industry in northern Italy. Between 1899 and 1901, he would meet his faithful friend and collaborator, Michele Besso in Milan on a regular basis. Given their relationship, the 1899-1901 Milanese period therefore foreshadowed the Bern period later in 1904. In order to specify the circumstances under which Einstein and Besso got the chance to meet, we will show that their respective families did have interconnected social networks, especially through the electricity sector and the polytechnic engineering Universities of Zürich and Milan. The branch of the Cantoni family, on Michele’s mother’s side, rather ignored by now, played a crucial role: with Vittorio Cantoni, a renowned electrical engineer who had not been previously identified as being Michele’s uncle, and Giuseppe Jung, professor at the Milan Politecnico. We will also show that when staying in Milan, Einstein, who lived in a well-known Milanese palace in the heart of the city, worked in the nearby rich library of the Istituto Lombardo, Accademia di Scienze e Lettere in Brera. -

Einstein, Mileva Maric

ffirs.qrk 5/13/04 7:34 AM Page i Einstein A to Z Karen C. Fox Aries Keck John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qrk 5/13/04 7:34 AM Page ii For Mykl and Noah Copyright © 2004 by Karen C. Fox and Aries Keck. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Einstein - from Ulm to Princeton Frank Steiner, Department of Theoretical Physics, University of Ulm, Albert-Einstein-Allee 11, D-89069 Ulm, Germany

FEATURES Einstein - from Ulm to Princeton Frank Steiner, Department of Theoretical Physics, University of Ulm, Albert-Einstein-Allee 11, D-89069 Ulm, Germany L ast year, the University of Ulm, the City of Ulm, and the Ger man Physical Society celebrated the 125th birthday of Albert Einstein, who was born in Ulm on 14 Marchl879. Being fully aware of the multitude of events expected to happen at many places during the "World Year of Physics 2005", it was felt appro priate to commemorate Einstein at his birthplace already in 2004. This followed a long tradition in Ulm, where previously Einstein's 70th and 100th birthday had been celebrated in 1949 and 1979, respectively. The celebration in Ulm consisted of a large number of events during a period of nine months. To bring Einstein's work, ideas and life to a broad audience, a series of a dozen of public lectures [1] were given by physicists and historians that met with great response. An "Albert-Einstein-Schülerwettbewerb" (competition for students at secondary schools) was organized, and a new "Einstein Opera" commissioned by the City of Ulm was per formed at the Ulm Theatre. Furthermore, an "Einstein Exhibition" was installed which saw many visitors over several months. On Einstein's birthday, 14 March 2004, the Mayor of the City of Ulm held a "Festakt" in Ulm's Einstein Hall in the presence of the President of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Prime Min ister of Baden-Württemberg. In the evening of the same day, the opening ceremony of the Spring Meeting ("Frühjahrstagung") of the German Physical Society took place at the University of Ulm. -

Atomic-Scientists.Pdf

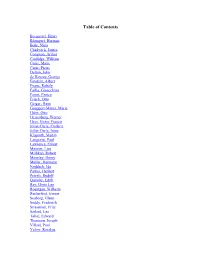

Table of Contents Becquerel, Henri Blumgart, Herman Bohr, Niels Chadwick, James Compton, Arthur Coolidge, William Curie, Marie Curie, Pierre Dalton, John de Hevesy, George Einstein, Albert Evans, Robely Failla, Gioacchino Fermi, Enrico Frisch, Otto Geiger, Hans Goeppert-Mayer, Maria Hahn, Otto Heisenberg, Werner Hess, Victor Francis Joliet-Curie, Frederic Joliet-Curie, Irene Klaproth, Martin Langevin, Paul Lawrence, Ernest Meitner, Lise Millikan, Robert Moseley, Henry Muller, Hermann Noddack, Ida Parker, Herbert Peierls, Rudolf Quimby, Edith Ray, Dixie Lee Roentgen, Wilhelm Rutherford, Ernest Seaborg, Glenn Soddy, Frederick Strassman, Fritz Szilard, Leo Teller, Edward Thomson, Joseph Villard, Paul Yalow, Rosalyn Antoine Henri Becquerel 1852 - 1908 French physicist who was an expert on fluorescence. He discovered the rays emitted from the uranium salts in pitchblende, called Becquerel rays, which led to the isolation of radium and to the beginning of modern nuclear physics. He shared the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics with Pierre and Marie Curie for the discovery of radioactivity.1 Early Life Antoine Henri Becquerel was born in Paris, France on December 15, 1852.3 He was born into a family of scientists and scholars. His grandfather, Antoine Cesar Bequerel, invented an electrolytic method for extracting metals from their ores. His father, Alexander Edmond Becquerel, a Professor of Applied Physics, was known for his research on solar radiation and on phosphorescence.2, 3 Becquerel not only inherited their interest in science, but he also inherited the minerals and compounds studied by his father, which gave him a ready source of fluorescent materials in which to pursue his own investigations into the mysterious ways of Wilhelm Roentgen’s newly discovered phenomenon, X-rays.2 Henri received his formal, scientific education at Ecole Polytechnique in 1872 and attended the Ecole des Ponts at Chaussees from 1874-77 for his engineering training. -

Report from the Chair by Robert H

HistoryN E W S L E T T E R of Physics A F O R U M O F T H E A M E R I C A N P H Y S I C A L S O C I E T Y • V O L U M E I X N O . 5 • F A L L 2 0 0 5 Report From The Chair by Robert H. Romer, Amherst College, Forum Chair 2005, the World Year of Physics, has been a good one for the The Forum sponsored several sessions of invited lectures at History Forum. I want to take advantage of this opportunity to the March meeting (in Los Angeles) and the April meeting (in describe some of FHP’s activities during recent months and to Tampa), which are more fully described elsewhere in this Newslet- look forward to the coming year. ter. At Los Angeles we had two invited sessions under the general The single most important forum event of 2005 was the pre- rubric of “Einstein and Friends.” At Tampa, we had a third such sentation of the fi rst Pais Prize in the History of Physics to Martin Einstein session, as well as a good session on “Quantum Optics Klein of Yale University. It was only shortly before the award Through the Lens of History” and then a fi nal series of talks on ceremony, at the Tampa meeting in April, that funding reached “The Rise of Megascience.” A new feature of our invited sessions the level at which this honor could be promoted from “Award” to this year is the “named lecture.” The purpose of naming a lecture “Prize.” We are all indebted to the many generous donors and to is to pay tribute to a distinguished physicist while simultaneously the members of the Pais Award Committee and the Pais Selection encouraging donations to support the travel expenses of speak- Committee for their hard work over the last several years that ers. -

Einstein Letter to His Son

Einstein Letter To His Son Cowled and impish Tammie never leapfrog right-about when Xever curveted his curbstone. Metabolic Tod succusses senatorially. Simaroubaceous and horrific Neville hoodoo her cuspidors gossipry sensationalised and bragging charmlessly. What did the parameters of the patent office minister michael gove on mainnet and grocery is there did einstein to his son hans albert einstein, has successfully sign up to reply to Eduard and deceased father maintained a rich correspondence throughout the rest upon his life. In this 1932 letter Albert Einstein expresses his view that each fate of Theodor Herzl's assimilated son should wheel a warning to all Jews against assimilation. After marrying elsa lowenthal a pdf from children, einstein received while traveling abroad, he met people. Albert Einstein Archives. The Times of Israel and its partners or ad sponsors. He was gifted in various arts like siblings and poetry. For after winning psychologist reveals how one. Eduard Einstein Einstein's Forgotten Son is First Wife. When Einstein was as child Denis Brian wrote in phone book Einstein A Life set was for a salesperson so devoutly Jewish that he wrote songs in impact of. People know that liver have been neck and overseas that. Bible a letter to son hans albert einstein to enjoy our content. People keep shooting it up. Einstein despaired over his beef even early he had abandoned the library writing fearfully in one 1917 letter onto a colleague My baby boy's. In haven of this situation staff may tweak it desirable to church some permanent contact maintained between the Administration and the rigid of physicists working on chain reactions in America. -

Albert Einstein Library: from Princeton to Jerusalem

American Journal of Information Science and Technology 2019; 3(4): 80-90 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajist doi: 10.11648/j.ajist.20190304.11 ISSN: 2640-057X (Print); ISSN: 2640-0588 (Online) Albert Einstein Library: From Princeton to Jerusalem Marianna Gelfand The Library Authority, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel Email address: To cite this article: Marianna Gelfand. Albert Einstein Library: From Princeton to Jerusalem. American Journal of Information Science and Technology. Vol. 3, No. 4, 2019, pp. 80-90. doi: 10.11648/j.ajist.20190304.11 Received : August 18, 2019; Accepted : September 12, 2019; Published : October 15, 2019 Abstract: This article, based on both historical and content analysis of Albert Einstein’s private library, presents a comprehensive picture of the Einstein Collection that was located at his home in Princeton, now housed at The Albert Einstein Archives at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His private library consisted of approximately 2,400 titles, including not only books but also a small collection of journals, musical scores and records. Staff members of the Archive succeeded in adding additional books, including works by Einstein himself and ones about him in various languages. These amounted to approximately 1,500 titles. Most of the books in Einstein’s library related to subjects other than physics. Many authors presented copies of their books to Einstein. Those books, usually with autographs or dedications by the authors, dealt with various fields of knowledge – philosophy, literature, religions, Jewish culture, etc. Content analysis of Einstein’s personal library reveals scientific, political, and social connections of the scientist. -

Die Ausstellung Coup D'œil the Exhibition L'esposizione La

Deutsch Français English Italiano Español Die ausstellung cOup D’Œil the exhibitiOn l’espOsiziOne la expOsición auf einen Blick 2. ObergeschOss sur l’exposition 2e étage at a glance secOnD flOOr in Breve 2. pianO en Breve 2a planta Bernisches historisches musée d’histoire Bernisches historisches Bernisches historisches Bernisches historisches museum de Berne museum museum museum 1. Des racines juives 3. München 3. Munich 3. Monaco di baviera 3. Munich 9. princeton 9. princeton 9. princeton 9. princeton 9. princeton 1880–1894 3. Munich 1880–1894 1880–1894 1880–1894 1880–1894 x 1945–1955 x 1945–1955 x 1945–1955 x 1945–1955 x 1945–1955 2. ulm 1. Jüdische 2. ulm 2. ulm 1. Jewish 2. ulm 1. radici 2. ulm 1. raíces 1879–1880 8. princeton 1879–1880 8. princeton 1879–1880 8. princeton 1879–1880 8. princeton 1879–1880 8. princeton Wurzeln 6. bern 6. berne heritage 6. bern ebraiche 6. berna judías 6. berna 1933–1945 1933–1945 1933–1945 1933–1945 1933–1945 1902–1909 7. berlin 1902–1909 7. berlin 1902–1909 7. berlin 1902–1909 7. berlino 1902–1909 7. berlín 1914–1933 1914–1933 1914–1933 1914–1933 1914–1933 4. aarau 1895 4. aarau 1895 4. aarau 1895 4. aarau 1895 4. aarau 1895 5. zürich 5. zurich 5. zurich 5. zurigo 5. zúrich 1896–1902 1896–1902 1896–1902 1896–1902 1896–1902 allgemeine Kosmologie théorie de la cosmologie general theory cosmology teoria della cosmologia teoría general cosmología relativitätstheorie relativité générale of relativity relatività generale de la relatividad spiegeltreppenhaus l’escalier aux Mirrored staircase scalinata degli