Using Cued Speech to Support Literacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for the Assessment of Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing Children In

Guidelines for the Assessment and Educational Evaluation of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Children in Indiana Based on 511 IAC Article 7, 2008 Effective Date: August 13, 2008 Revised Date: August 31, 2010 Updated Date: November 15, 2013 [1] This document is dedicated to all deaf and hard-of- hearing children in Indiana and their families. Since 1843, deaf and hard-of-hearing children have been educated in this state and many leave our schools, go out into the world, and become productive citizens. Some children in the past have not been so fortunate and may not have left the educational system with the knowledge and tools to maximize their potential. This guide was developed to help educators use assessment information and evaluations to assist parents and the case conference committees in determining how a child can reach their full potential. Advances in technology, as well as greater knowledge of how the brain functions and how language is acquired, have helped the professionals who work with this population provide information that will lead to informed decision making. This guide was made possible by the teamwork and collaboration of audiologists, psychologists, speech pathologists, language specialists, social workers, and parents. Special gratitude is extended to Linda Charlebois and Terri Waddell-Motter who took the lead in assembling this information. We also thank additional contributors, including (and not limited to) Carolyn Pimentel, Lorinda Bartlett, Pam Burchett, Debra Liebrich, Louise Fitzpatrick, Sheryl Whiteman, Carol Wild, Shannon Stafford, Jackie Katter, Janet Fuller, and Joyce Conner. Guidelines for the Assessment and Educational Evaluation of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Children in Indiana, based on the Article 7 changes of 2008, was developed by Outreach Services for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Children. -

Speechreading for Information Gathering

Speechreading for information gathering: A survey of scientific sources1 Ruth Campbell Ph.D, with Tara-Jane Ellis Mohammed, Ph.D Division of Psychology and Language Sciences University College London Spring 2010 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 Questions (and answers) 3 Chronologically organised survey of tests of Speechreading (Tara Mohammed) 4 Further Sources 5 Biographical notes 6 References 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This report aims to clarify what is and is not possible in relation to speechreading, and to the development of speechreading skills. It has been designed to be used by agencies which may wish to make use of speechreading for a variety of reasons, but it focuses on requirements in relation to understanding silent speech for information gathering purposes. It provides the main evidence base for the report : Guidance for organizations planning to use lipreading for information gathering (Ruth Campbell) - a further outcome of this project. 1.2 The report is based on published, peer-reviewed findings wherever possible. There are many gaps in the evidence base. Research to date has focussed on watching a single talker’s speech actions. The skills of lipreaders have been scrutinised primarily to help improve communication between the lipreader (typically a deaf or deafened person) and the speaking hearing population. Tests have been developed to assess individual differences in speechreading skill. Many of these are tabulated below (section 3). It should be noted however that: There is no reliable scientific research data related to lipreading conversations between different talkers. There are no published studies of expert forensic lipreaders’ skills in relation to information gathering requirements (transcript preparation, accuracy and confidence). -

An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS

An Inefficient Choice: An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ted Michael Dickinson Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Jesse Fox, Advisor Dr. Brandon van der Heide Copyrighted by Ted Michael Dickinson 2012 Abstract Media richness theory is frequently cited when discussing the strengths of various media in allowing for immediate feedback, personalization of messages, the ability to use natural language, and transmission of nonverbal cues. Most studies do not, however, address the theory’s main argument that people faced with equivocal message tasks will complete those tasks faster by choosing interpersonal communication media with these features. Participants in the present study either chose or were assigned to a medium and then timed on their completion of an equivocal message task. Findings support media richness theory’s prediction; those using videoconferencing to complete the task did so in less time than those using the leaner medium of text chat. Measures of electronic propinquity, a theory proposing a sense of psychological nearness to others in a mediated communication, were also tested as a potential adjunct to media richness theory’s predictions of medium selection, with mixed results. Keywords: media richness, electronic propinquity, media selection, computer-mediated communication, nonverbal -

Read-My-Lips: a Multimedia Project for the Hearing

JOAQUIN VILA and KATHLEEN M. AHLERS READ-MY -LIPS: A MULTIMEDIA PROJECT FOR THE HEARING IMPAIRED Read-My-Lips is an interactive multimedia system designed to help instructors teach language and communication skills to the hearing-impaired. The system comprises three multimedia instructional modules. (1) Babel is an expert system that translates text to speech in any language that uses the Roman alphabet. This module depicts the process of speech by displaying a front view and a profIle cross view of a human face in synchronization with the output sounds of a speech synthesizer. (2) Read & See consists of a series of stories and games that are displayed with text and full video motion. Selected vocabulary within the story is signed and spoken using digitized video sequences. (3) Fingerspelling allows the student to request any word or number to be "fingerspelled." INTRODUCTION The computer has become a popular instructional tool available from the Alexander Graham Bell Association used in school programs for the hearing-impaired. l Many for the Deaf, use drill and practice methods for the computer programs are geared exclusively to the presen speech-reading of everyday utterances. tation and practice of academic content.2 Yet several As technology has improved, interactive video has software packages for the hearing-impaired focus on been used in designing speech-reading programs. A sys specific speech, speech-reading, and/or auditory skills. tem titled DAVID6 (dynamic audio video interactive de Hearing-impaired students have great difficulty master vice) was created in 1978. It requires students to view ing these skills because of their degree of hearing loss. -

Poor Print Quality

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 476 841 FL 027 697 AUTHOR Kontra, Miklos TITLE British Aid for Hungarian Deaf Education from a Linguistic Human Rights Point of View. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 9p.; An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Biennial Conference of the Hungarian Society for the Study of English (4th, Budapest, Hungary, January 28-30, 1999). Some parts contain light or broken text. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) Reports Descriptive (141) JOURNAL CIT Hungarian Journal of Applied Linguistics; vl n2 p63-68 2001 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Deafness; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Oral Communication Method; *Sign Language; Speech Communication; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Hungary; United Kingdom ABSTRACT This paper discusses the issue of oral versus sign language in educating people who are deaf, focusing on Hungary, which currently emphasizes oralism and discourages the use of Hungarian Sign Language. Teachers of people who are hearing impaired are trained to use the acoustic channel and view signing as an obstacle to the integration of deaf people into mainstream Hungarian society. A recent news report describes how the British. Council is giving children's books to a Hungarian college for teachers of handicapped students, because the college believes in encouraging hearing impaired students' speaking skills through picture books rather than allowing then to use sign language. One Hungarian researcher writes that the use of Hungarian Sign Language hinders the efficiency of teaching students who are hard of hearing, because they often prefer it to spoken Hungarian. This paper suggests that the research obscures the difference between medically deaf children, who will never learn to hear, and hearing impaired children, who may learn to hear and speak to some extent. -

Building Pedagogical Curb Cuts: Incorporating Disability in the University Classroom and Curriculum 4105-11 SU 4/1/05 3:50 PM Page 4

4105-11_SU 4/1/05 3:50 PM Page 3 Building Pedagogical Curb Cuts: Incorporating Disability in the University Classroom and Curriculum 4105-11_SU 4/1/05 3:50 PM Page 4 Copyright 2005© The Graduate School, Syracuse University. For more information about this publication, contact: The Graduate School Syracuse University 423 Bowne Hall Syracuse, New York 13244. 4105-11_SU 4/1/05 3:50 PM Page 5 v Contents Acknowledgements vii Chancellor’s Preface ix Editors’ Introduction xi I. Incorporating Disability in the Curriculum Mainstreaming Disability: A Case in Bioethics 3 Anita Ho Language Barriers and Barriers to Language: Disability 11 in the Foreign Language Classroom Elizabeth Hamilton and Tammy Berberi Including Women with Disabilities in Women and 21 Disability Studies Maria Barile Seeing Double 33 Ann Millett Cinematically Challenged: Using Film in Class 43 Mia Feldbaum and Zach Rossetti “Krazy Kripples”: Using South Park to Talk 67 about Disability Julia White Teaching for Social Change 77 Kathy Kniepmann II. Designing Instruction for Everyone Nothing Special: Becoming a Good Teacher for All 89 Zach Rossetti and Christy Ashby 4105-11_SU 4/1/05 3:50 PM Page 6 vi contents Tools for Universal Instruction 101 Thomas Argondizza “Lame Idea”: Disabling Language in the Classroom 107 Liat Ben-Moshe Learning from Each Other: Syracuse University 117 and the OnCampus Program Cheryl G. Najarian and Michele Paetow III. Students with Disabilities in the Classroom Being an Ally 131 Katrina Arndt and Pat English-Sand Adapting and “Passing”: My Experiences as a 139 Graduate Student with Multiple Invisible Disabilities Elizabeth Sierra-Zarella “We’re not Stupid”: My College Years 147 as a Mentally Challenged Student Anthony J. -

The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 414 CS 504 984 AUTHOR McQuillen, Jeffrey S.;Ivy, Diana K. TITLE The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future. PUB DATE [82] NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Basic Skills; Course Content; Course Organization; Educational Assessment; *Educational History; Educational Trends; Higher Education; *Speech Communication; *Speech Curriculum; Speech Instruction ABSTRACT Acknowledging the need for objective evaluation of. the focus and organization of the basic speechcommunication course, this paper reviews the progress of the basic course bytracing its changes and development. The first portion of the paperdiscusses the evolution of the basic course from the 1950s to the present,giving specific attention to historical modifications in thebasic course's orientation and focus. The second, portion of the paperaddresses questions concerning the current orientation,responsiveness, and appropriateness of the basic course, and reviewspromising answers to these questions. (HTH) ********************************************************************** * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** BEST COPY AVAILABLE THE BASIC COURSE IN SPEECH COMMUNICATION: Past, present and r--1 future CT r\J LtJ Jeffrey S. McQuillen Assistant Professor Speech Communication Program Texas ALCM University College Station, TX 77843 (409) 845-8328 Diana K. Ivy Doctoral Candidate Communication Department University of Oklahoma Norman, Ok 73019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL. RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERICI .>\Thisdocument has been reproduced as eceived from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality Points of view or opinions :riled in this dorm merit do not necessarily represent official NIE position or petit. -

The Transition from Fingerspelling to English Print: Facilitating English Decoding

The Transition From Fingerspelling to English Print: Facilitating English Decoding Tamara S. Haptonstall-Nykaza Colorado School for the Deaf and the Blind Brenda Schick University of Colorado, Boulder Fingerspelling is an integral part of American Sign Lan- orthography available in most written systems. Re- guage (ASL) and it is also an important aspect of becoming search on hearing children’s development of reading bilingual in English and ASL. Even though fingerspelling is has found strong connections between children’s pho- based on English orthography, the development of finger- spelling does not parallel the development of reading in nological systems and awareness of phonological reg- hearing children. Research reveals that deaf children may ularities and their ability to read (see Snow, Burns, & initially treat fingerspelled words as lexical items rather than Griffin, 1998). Typically, reading is viewed, in large a series of letters that represent English orthography and part, as reflecting English skills, and deaf children’s only later begin to learn to link handshapes to English gra- longstanding difficulties with learning to read are con- phemes. The purpose of this study is to determine whether a training method that uses fingerspelling and phonological sidered to be a problem with English (King & Quigley, patterns that resemble those found in lexicalized finger- 1985; Paul, 1998). More recently, researchers have be- spelling to teach deaf students unknown English vocabulary gun to investigate how American Sign Language, or would increase their ability to learn the fingerspelled and ASL, can support and facilitate reading in English (see orthographic version of a word. There were 21 deaf students (aged 4–14 years) who participated. -

Early Intervention: Communication and Language Services for Families of Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing Children

EARLY INTERVENTION: COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE SERVICES FOR FAMILIES OF DEAF AND HARD-OF-HEARING CHILDREN Our child has a hearing loss. What happens next? What is early intervention? What can we do to help our child learn to communicate with us? We have so many questions! You have just learned that your child has a hearing loss. You have many questions and you are not alone. Other parents of children with hearing loss have the same types of questions. All your questions are important. For many parents, there are new things to learn, questions to ask, and feelings to understand. It can be very confusing and stressful for many families. Many services and programs will be available to you soon after your child’s hearing loss is found. When a child’s hearing loss is identified soon after birth, families and professionals can make sure the child gets intervention services at an early age. Here, the term intervention services include any program, service, help, or information given to families whose children have a hearing loss. Such intervention services will help children with hearing loss develop communication and language skills. There are many types of intervention services to consider. We will talk about early intervention and about communication and language. Some of the services provided to children with hearing loss and their families focus on these topics. This booklet can answer many of your questions about the early intervention services and choices in communication and languages available for you and your child. Understanding Hearing Loss Timing: The age when a hearing loss has occurred is known as “age of onset.” You also might come across the terms prelingual and postlingual. -

UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech

UNITED NATIONS STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Foreword Around the world, we are seeing a disturbing groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance – including rising anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim hatred and persecution of Christians. Social media and other forms of communication are being exploited as platforms for bigotry. Neo-Nazi and white supremacy movements are on the march. Public discourse is being weaponized for political gain with incendiary rhetoric that stigmatizes and dehumanizes minorities, migrants, refugees, women and any so-called “other”. This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream – in liberal democracies and authoritarian systems alike. And with each broken norm, the pillars of our common humanity are weakened. Hate speech is a menace to democratic values, social stability and peace. As a matter of principle, the United Nations must confront hate speech at every turn. Silence can signal indifference to bigotry and intolerance, even as a situation escalates and the vulnerable become victims. Tackling hate speech is also crucial to deepen progress across the United Nations agenda by helping to prevent armed conflict, atrocity crimes and terrorism, end violence against women and other serious violations of human rights, and promote peaceful, inclusive and just societies. Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech. It means keeping hate speech from escalating into something more dangerous, particularly incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence, which is prohibited under international law. The United Nations has a long history of mobilizing the world against hatred of all kinds through wide-ranging action to defend human rights and advance the rule of law. -

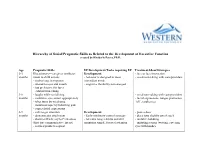

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Auditory-Verbal

*Communication Building Blocks A review of choices in communication A smile, a cry, a gesture, or a look – all can communicate thoughts or ideas. It can take many repetitions of a gesture, look, word, phrase, or sound before a child begins to “break the code” between communication attempts and real meaning. Communication surrounding the child in his or her natural environment is the basis for a child’s language development. Two-way communication, responding to your child and encouraging your child to respond to you, is the key to your child’s language development. When a child has a hearing loss, one avenue of communication input is impaired. With a mild hearing loss or hearing loss in just one ear, a child will not hear as well as normal when a person is speaking from another room or in a noisy car. Incidental conversations and snippets of language will not be overheard. The fullness of language and social skills may be affected even though the child appears to “hear”. Hearing aids can help, but not solve all of the child’s difficulties perceiving soft or distant speech. Children with greater degrees of hearing loss will have greater hearing limitations that require more intensive attention if they are to progress in learning language, either through visual or auditory means. No matter what the degree of a child’s hearing loss, parents need to decide how to adapt their normal communication style to meet the needs of their baby with hearing impairment. There are different ways to communicate and different philosophies about communication.