Weaknesses and Capacities Affecting the Prehospital Emergency Care For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Namuwongo: Key to Kampala’S Present and Future Development

5/8/2017 Africa at LSE – Namuwongo: Key to Kampala’s Present and Future Development Namuwongo: Key to Kampala’s Present and Future Development Ahead of an exhibition celebrating the Kampala neighbourhood, Namuwongo, Joel Ongwec showcases the contribution this informal settlement and its inhabitants to Uganda’s capital city. Kampala is the largest city of Uganda with over 1.5 million residents. Its rapid population growth has put pressure on the municipality to deliver basic services as up to 60 per cent of the population are living in informal settlements (Mukwaya et al. 2010). Informal areas such as the centrally located Namuwongo have experienced protests over evictions and lack of urban services, including administrative problems that link into wider resource conflicts across the city (Kareem and Lwasa 2011). The need to undertake research to better understand these areas is pressing and a group of researchers including myself have spent time in Namuwongo to consider the issues of urban spaces like this and others across the capital. We sought to address this with research that concludes with an exhibition at the Uganda National Museum. Namuwongo is an informal settlement which separates two wealthier neighbourhoods of Bugolobi and Muyenga just outside the city centre. It spreads out along the main drainage channel (Nakivubo) that pours its water into Lake Victoria. The settlement has spilled over the railroad tracks as a result of people moving to the capital and currently has an estimated 15,000 inhabitants, several businesses, churches, and even large logistics warehouses. It is however a poorly understood neighborhood, but a vital one to the present and future of Kampala. -

Jakana Heights Apartments: High-Quality Design with the Finest Finishes

Jakana Heights Luxury Hilltop Living Kampala, Uganda Jakana Heights Welcome to Jakana Heights First-class, luxury living in Kampala “Our aim is to build an outstanding, quality residential development, one that is exciting and pleasureable to live in and, for those who chose to rent, yields excellent financial returns. “As an international property developer I know the standard of build and finish Uganda diaspora customers from the UK and US have come to enjoy, and I have every confidence Jakana Heights will fulfill those high expectations.” Clive Kefford Principal Property Developer Jakana Heights 1 Jakana Heights Jakana Heights: Unrivalled style on Konge Hill When you become a Jakana Heights resident, you gain one of the most desirable addresses in Kampala. Set in a commanding position above the city, you’ll find the climate fresh and clean, and the surroundings relaxed and verdant. Yet all the popular business and social neighbourhoods you need are within easy reach: the city centre, Speke resort, Lake Victoria, and the Munyonyo district are all a short drive away. And with the improved, extended road network linking the new Entebbe highway to the foot of Konge Hill, getting to and from the airport is a swift, trouble-free 25 minute journey. WILD BUSHES Jakana Heights: Masterplan An exclusive development of 76 luxury units on a spectacular hilltop site with uninterrupted views to Lake Victoria, set in 3.4 acres of VERTICAL GARDEN landscaped gardens. 1 Bedroom Apartments UPPER BLOCK 2 Bedroom Apartments 3 Bedroom Apartments GATEHOUSE -

Uganda 2020 Human Rights Report

UGANDA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uganda is a constitutional republic led since 1986 by President Yoweri Museveni of the National Resistance Movement party. In 2016 voters re-elected Museveni to a fifth five-year term and returned a National Resistance Movement majority to the unicameral parliament. Allegations of disenfranchisement and voter intimidation, harassment of the opposition, closure of social media websites, and lack of transparency and independence in the Electoral Commission marred the elections, which fell short of international standards. The periods before, during, and after the elections were marked by a closing of political space, intimidation of journalists, and widespread use of torture by the security agencies. The national police maintain internal security, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs oversees the police. While the army is responsible for external security, the president detailed army officials to leadership roles within the police force. The Ministry of Defense oversees the army. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous abuses. Significant human rights issues included: unlawful or arbitrary killings by government forces, including extrajudicial killings; forced disappearance; torture and cases of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment by government agencies; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest or detention; political prisoners or detainees; serious problems with the -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

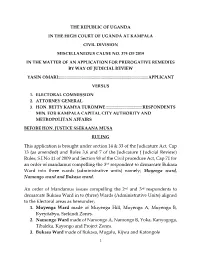

This Application Is Brought Under Section 14 & 33 of the Judicature Act, Cap 13

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA CIVIL DIVISION MISCELLANEOUS CAUSE NO. 374 OF 2019 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION FOR PREROGATIVE REMEDIES BY WAY OF JUDICIAL REVIEW YASIN OMARI :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::::::: ::::::::: :::::::::::::::::::::::APPLICANT VERSUS 1. ELECTORAL COMMISSION 2. ATTORNEY GENERAL 3. HON. BETTY KAMYA TUROMWE :::: :::::::::::::::::::::: ::::::::RESPONDE NT S MIN. FOR KAMPALA CAPITAL CITY AUTHORITY AND METROPOLITAN AFFAIRS BEFORE HON. JUSTICE SSEK AANA MUSA RULING This application is brought under section 14 & 33 of the Judicature Act, Cap 13 (as amended) and Rules 3,6 and 7 of the Judicature ( Judicial Review) Rules, S.I No 11 of 2009 and Section 98 of the Civil procedure Act, Cap 71 for an order of mandamus compelling the 3 rd respondent to demarcate Bukasa W ard into three wards (administrative units) namely; Muyenga ward, Namongo ward and Bukasa ward. An order of Mandamus issues compelling the 2 nd and 3 rd respondents to demarcate Bukasa Ward in to (three) Wards (Administrative Units) aligned to the Electoral areas as hereunder; 1. Muyenga Ward made of Muyenga Hill, Muyenga A, Muyenga B, Kyeyitabya, Ssekindi Zones. 2. Namongo Ward made of Namongo A, Namongo B, Yo ka, Kanyogoga , Tibaleka, Kayongo and Project Zones. 3. Bukasa Ward made of Bukasa, Mugalu, Kijwa and Katongole 1 A t the time of filing this application on the 4 th September 2019, the 1 st respondent had not undertake n the demarcation of electoral areas. subseque ntly, this was done and communicated to the applicant by letter dated 17 th September 2019. T he applicant faults the 3 rd respondent in his supplementary affidavit for failing to make a decision on whether or not to demarcate Bukasa ward into 3 administrativ e units an act he alleges is irrational, illegal and arbitrary. -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3 -

Sustainable Utilisation of Energy and Biodiversity Resources for Wealth Creation and Development’, 10–13 March 2009, Kampala, Uganda

International Roundtable on ‘Sustainable Utilisation of Energy and Biodiversity Resources for Wealth Creation and Development’, 10–13 March 2009, Kampala, Uganda. Introduction The increasing population pressure and demand for a better life style have necessitated a need for greater use of energy. This has resulted in mounting pressure on the use of available resources which is now mostly met by fossil fuels. The rate of energy consumption is much higher than it was ever before and the demand is on increase. There is a negative balance between source depletion and replenishment by natural processes. This has also resulted in uncontrollable rise in pollution due to air, water, soil and noise besides electro-pollution, causing the very survival of life difficult on Planet Earth. An increase in the level of carbon dioxide, possibly causing a temperature rise leading to global warming and subsequent melting of glaciers culminating into climate change is a phenomenon of utmost concern. This has serious economic and social implications. Climate change linked to emissions is then about limiting growth, and also sharing growth among nations which has its economic overtones. The emerging scenario has led to a tremendous pressure on survival of species type (both plants and animals). The number of such species is registering a significant decline, thereby posing a serious threat to the sustainability of ecosystem itself. A demand for green energy is understood but the quantum and nature of its exploitation remains to be settled. Solar, the ultimate source of energy is now widely discussed, though increase in its efficiency usage is still a matter of continued investigation. -

Makindye Division Grades

DIVISION PARISH VILLAGE STREET AREA GRADE MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA BENYA ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA BUKASA ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA BUKASA STREET 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA JOSEPH KIYINGI VALLEY 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA KIYINGI BY PASS 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA MUYENGA ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA BUKASA RING ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 2ND CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 3RD CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 5 TC 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 5TH CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 6TH CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 8TH CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA 8TH STREET 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA BBALE CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA BUKASA ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA KIRONDE ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYOGOGA OFF NAMUWONGO ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA ALICE MUWANGA CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA KIALER ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA KIBIRANGO ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA KIRONDE CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA KIRONDE ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA LWANGA CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA MPAGI LANE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA MUSAAZI AHMED ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA MUSAAZI ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA MUWAFU ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA MUYENGA ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA MUYENGA TANKHILL ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA NABULIME CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA NKUSSA CLOSE 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA NYANGWESO ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA OFF KIRONDE ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA OFF MUSAAZI ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA OFF RING ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA OFF TANKHILL ROAD 1 MAKINDYE BUKASA KANYONZA -

Press Release

t The Reoublic of LJoanda MINISTRY OF HEALTH Office of the Director General 'Public Relations Unit 256-41 -4231 584 D i rector Gen era l's Off ice : 256- 41 4'340873 Fax : PRESS RELEASE IMPLEMENTATION OF HEPATITIS B CONTROL ACTIVITIES IN I(AMPALA METROPOLITAN AREA Kampala - 19th February 2O2l' The Ministry of Health has embarked on phase 4 of the HePatitis B control activities in 31 districts including Kampala Metropolitan Area.- These activities are expected to run uP to October 2021 in the districts of imPlementation' The hepatitis control activities include; 1. Testing all adolescents and adults born before 2OO2 (19 years and above) 2. Testing and vaccination for those who test negative at all HCIIIs, HCIVs, General Hospitals, Regional Referral Hospitals and outreach posts. 3. Linking those who test positive for Hepatitis B for further evaluation for treatment and monitoring. This is conducted at the levels of HC IV, General Hospitals and Regional Referral Hospitals' The Ministry through National Medical Stores has availed adequate test kits and vaccines to all districts including Kampala City Courrcil' Hepatitis + Under phase 4, ttle following districts will be covered: Central I Regi6n: Kampala Metropolitan Area, Masaka, Rakai, Kyotera, Kalangala, Mpigi, Bffiambala, Gomba, Sembabule, Bukomansimbi, Lwen$o, Kalungu and Lyantonde. South Western region: Kisoro, Kanungu, Rubanda, Rukiga, Rwampara, Rukungiri, Ntungamno, Isingiro, Sheema, Mbarara, Buhweju, Mitooma, Ibanda, Kiruhura , Kazo, Kabale, Rubirizi and Bushenyi. The distribution in Kampala across the five divisions is as follows: Kawempe Division: St. Kizito Bwaise, Bwaise health clinic, Pillars clinic, Kisansa Maternity, Akugoba Maternity, Kyadondo Medical Center, Mbogo Health Clinic, Mbogo Health Clinic, Kawempe Hospital, Kiganda Maternity, Venus med center, Kisaasi COU HC, Komamboga HC, Kawempe Home care, Mariestopes, St. -

(Ursb): Notice to the Public on Marriage Registration

NOTICE TO THE PUBLIC ON MARRIAGE REGISTRATION Uganda Registration Services Bureau (URSB) wishes to inform the general public that all marriages conducted in Uganda MUST be filed with the Registrar of Marriages. The public is reminded that only church marriages conducted in Licensed and Gazetted places of worship are registrable and it is the duty of the licensed churches to file a record of the celebrated marriages with the Registrar of Marriages by the 10th day of every month, the marriages conducted under the Islamic Faith and the Hindu faith must be registered within three months from the date of the marriage and the Customary marriages must be registered at the Sub-County or Town council where the marriage took place within six months from the date of the marriage. Wilful failure to register marriages celebrated by the Marriage Celebrants violates the provisions of the Marriage Act and criminal proceedings may be instituted against them for failure to perform their statutory duties. The Bureau takes this opportunity to appreciate all Marriage Celebrants who are compliant. The public is hereby informed of the compliance status of Faith Based Organizations as at January 2021. MERCY K. KAINOBWISHO REGISTRAR GENERAL BORN AGAIN CHURCHES ELIM PENTECOSTAL CHURCH 01/30/2020 KYABAKUZA FULLGOSPEL CHURCH MASAKA 01/06/2020 PEARL HAVEN CHRISTIAN CENTER CHURCH 03/03/2020 UNITED CHRISTIAN CENTRE-MUKONO 11/19/2019 FAITH BASED ORGANIZATION DATE OF ELIM PENTECOSTAL CHURCH KAMPALA 08/27/2020 KYAMULIBWA WORSHIP CENTRE 09/11/2018 PEARL HEAVEN CHRISTIAN -

The Politics of Primary Education in Uganda: Parent Participation and National Reforms

THE POLITICS OF PRIMARY EDUCATION IN UGANDA: PARENT PARTICIPATION AND NATIONAL REFORMS NANSOZI K. MUWANGA A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Pbilosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto @Copyright by Nansozi K. Muwanga 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*I of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pe~ssion. autorisation. Educational reforms in Uganda since 1986, culrninating in the introduction of Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1996, attempted to reestablish centralized control over education and, by implication, reverse the trend toward the unregulated involvement in education of both of parents and non-state institutions. These reforms ran counter to existing participatory pattems of educational financing and administration, as well as to the political philosophy underpinning the National Resistance Movement (NRM) governrnent, i.e., democratization and popular participation in decision-making and service delivery. -

The Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, Plans and Their Implementation in Kampala City 1903-2004

School of Built Environment, CEDAT Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda and School of Architecture and the Built Environment Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden The Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, Plans and their Implementation in Kampala City 1903-2004 Fredrick Omolo-Okalebo Doctoral Thesis in Infrastructure, Planning and Implementation Stockholm 2011 i ABSTRACT Title: Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, Plans and their Implementation in Kampala City 1903-2004 Through a descriptive and exploratory approach, and by review and deduction of archival and documentary resources, supplemented by empirical evidence from case studies, this thesis traces, analyses and describes the historic trajectory of planning events in Kampala City, Uganda, since the inception of modern town planning in 1903, and runs through the various planning episodes of 1912, 1919, 1930, 1951, 1972 and 1994. The planning ideas at interplay in each planning period and their expression in planning schemes vis-à-vis spatial outcomes form the major focus. The study results show the existence of two distinct landscapes; Mengo for the Native Baganda peoples and Kampala for the Europeans, a dualism that existed for much of the period before 1968. Modern town planning was particularly applied to the colonial city while the native city grew with little attempts to planning. Four main ideas are identified as having informed planning and transformed Kampala – first, the utopian ideals of the century; secondly, “the mosquito theory” and the general health concern and fear of catching „native‟ diseases – malaria and plague; thirdly, racial segregation and fourth, an influx of migrant labour into Kampala City, and attempts to meet an expanding urban need in the immediate post war years and after independence in 1962 saw the transfer and/or the transposition of the modernist and in particular, of the new towns planning ideas – which were particularly expressed in the plans of 1963-1968 by the United Nations Planning Mission.