Trade Mark Inter Partes Decision (O/031/12)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Profile of Hampton Bays, Phase I

HISTORIC PROFILE OF HAMPTON BAYS Phase I GOOD GROUND MONTAUK HIGHWAY CORRIDOR and CANOE PLACE MONTAUK HIGHWAY, GOOD GROUND 1935 by Charles F. Duprez Prepared by: Barbara M. Moeller June 2005 Additional copies of the HISTORIC PROFILE OF HAMPTON BAYS: Phase I May be obtained through Squires Press POB 995 Hampton Bays, NY 11946 $25 All profits to benefit: The Hampton Bays Historical & Preservation Society HISTORIC PROFILE OF HAMPTON BAYS INTRODUCTION: The Town of Southampton has sponsored this survey of his- toric resources to complement existing and forthcoming planning initiatives for the Hamlet of Hampton Bays. A Hampton Bays Montauk Highway Corridor (Hamlet Centers) Study is anticipated to commence in the near future. A review of Hampton Bays history and an inventory of hamlet heritage resources is considered a necessary component in order to help insure orderly and coordinated development within the Hamlet of Hampton Bays in a manner that respects community character. Hampton Bays United, a consortium of community organizations, spearheaded the initiative to complete a historical profile for Hampton Bays and a survey of hamlet heritage re- sources. The 2000 Hampton Bays Hamlet Center Strategy Plan adopted as an update to the 1999 Comprehensive Plan was limited to an area from the railroad bridge tres- tle on Montauk Highway near West Tiana Road (westerly border) to the Montauk Highway railroad bridge near Bittersweet Avenue (easterly border.) Shortly, the De- partment of Land Management will be preparing a “Hampton Bays Montauk High- way Corridor Land Use/Transportation Strategy Study” which will span the entire length of Montauk Highway from Jones Road to the Shinnecock Canal. -

Coffee Drinks 7

Coffee Drinks 7 Irish – whiskey, coffee and sugar Limerick – coffee liqueur and whiskey Royale – Celtic Crossing, coffee liqueur and Irish cream Butter Cream – butterscotch, Irish cream and whiskey Nutty Irishman – Irish cream and hazelnut liqueur Hot Toddy – whiskey, hot water, lemon and honey Milk & Honey – Irish cream, whiskey and Irish Mist Glass Wines - $6.5 glass Sauvignon Blanc / Pinot Grigio / Chardonnay Pinot Noir / Merlot / Cabernet Sauvignon Biutiful Cava Brut $7.5 Glass Ups - $9 Knicker Dropper Tito’s Vodka, Malibu Rum, Peach Schnapps, Pineapple and Cranberry Juice Cactus Peach Blossom Cuervo Gold Tequila, Peach Schnapps, Sour, Orange and Cranberry Juice “The light music of whiskey falling into a glass – an agreeable interlude.” -James Joyce Espresso Martini Absolut Vodka, Coffee Liqueur, Crème de Cacao & Coffee The Foggy Dew Tullamore D.E.W., Irish Mist, Amaretto, Ginger Ale and Soda Peaches and Cream West Cork Whiskey, Peach Schnapps, Irish Cream and Half & Half Fuars - $9 Limerick Tea Firefly Sweet Tea Vodka, Whisky, Celtic Crossing, Splash of Sour & Coke Dark & Stormy Gosling’s Black Seal Rum, Ginger Beer & Lime Juice “My favorite drink is a cocktail of carrot juice and whiskey. I am always drunk but can see for miles.” -Roy “Chubby” Brown Lucky Annie Celtic Honey, Cream de Cacao, RumChata, Rum, Soda Lime-Ricky Gin, Simple Syrup, Fresh Limes and Soda Nagshead Lemonade Bombay Gin, Triple Sec, Peach Schnapps, Lemons and Soda “When life hands you lemons, make whiskey sours.” -W.C. Fields Irish Palm Tree Malibu Rum, Celtic Crossing, Sour Mix, Pineapple Juice and Grenadine Shamrock Shaker The Knot Irish Whiskey Liquer, Irish Cream, Crème de Menthe, Crème de Cacao and Half & Half LG’s Elkin Street Green Hat Gin, Triple Sec, Fresh Lemon Juice, Simple Syrup and topped with Pinot Noir . -

The Beverage Company Liquor List

The Beverage Company Liquor List Arrow Kirsch 750 Presidente Brandy 750 Stirrings Mojito Rimmer Raynal Vsop 750 Glenlivet French Oak 15 Yr Canadian Ltd 750 Everclear Grain Alcohol Crown Royal Special Reserve 75 Amaretto Di Amore Classico 750 Crown Royal Cask #16 750 Amarito Amaretto 750 Canadian Ltd 1.75 Fleishmanns Perferred 750 Canadian Club 750 G & W Five Star 750 Canadian Club 1.75 Guckenheimer 1.75 Seagrams Vo 1.75 G & W Five Star 1.75 Black Velvet Reserve 750 Imperial 750 Canadian Club 10 Yr Corbys Reserve 1.75 Crown Royal 1.75 Kessler 750 Crown Royal W/Glasses Seagrams 7 Crown 1.75 Canadian Club Pet 750 Corbys Reserve 750 Wisers Canadian Whisky 750 Fleishmanns Perferred 1.75 Black Velvet Reserve Pet 1.75 Kessler 1.75 Newport Canadian Xl Pet Kessler Pet 750 Crown Royal 1.75 W/Flask Kessler 375 Seagrams Vo 375 Seagrams 7 Crown 375 Seagrams 7 Crown 750 Imperial 1.75 Black Velvet 375 Arrow Apricot Brandy 750 Canadian Mist 1.75 Leroux Blackberry Brandy 1ltr Mcmasters Canadian Bols Blackberry Brandy 750 Canada House Pet 750 Arrow Blackberry Brandy 750 Windsor Canadian 1.75 Hartley Brandy 1.75 Crown Royal Special Res W/Glas Christian Brothers Frost White Crown Royal 50ml Christian Broyhers 375 Seagrams Vo 750 Silver Hawk Vsop Brandy Crown Royal 375 Christian Brothers 750 Canada House 750 E & J Vsop Brandy Canada House 375 Arrow Ginger Brandy 750 Canadian Hunter Pet Arrow Coffee Brandy 1.75 Crown Royal 750 Korbel Brandy 750 Pet Canadian Rich & Rare 1.75 E&J Brandy V S 750 Canadian Ric & Rare 750 E&J Brandy V S 1.75 Seagrams Vo Pet 750 -

Aperitifs, Cordials, and Liqueurs

Chapter 6 Aperitifs, Cordials, and Liqueurs In This Chapter ▶ Serving up some tasty before-dinner drinks ▶ Examining the vast world of cordials and liqueurs his chapter is a catchall for a handful of different liquor Tcategories. Aperitifs were developed specifically as pre-meal beverages. Cordials and liqueurs have a variety of purposes. Some are great mixers, others are good after-dinner drinks, and a few make good aperitifs as well. Go figure. Whetting Your Appetite with Aperitifs Aperitif comes from the Latin word aperire, meaning “to open.” An aperitif is usually any type of drink you’d have before a meal. Most aperitifs are usually low in alcohol and mild-tasting. You can drink many of the cordials and liqueurs listed later in this chapter as aperitifs as well. I don’t have much more to say about aperitifs other than to list the individual products that are available, such as the following: ✓ Amer Picon (French): A blend of African oranges, gen- tian root, quinine bark, and some alcohol. Usually served with club soda or seltzer water with lemon. ✓ Campari (Italian): A unique combination of fruits, spices, herbs, and roots. 54 Part II: Distilling the High Points of Various Spirits ✓ Cynar (Italian): A bittersweet aperitif that’s made from artichokes. Best when served over ice with a twist of lemon or orange. ✓ Dubonnet (American): Produced in California and avail- able in blond and red. Serve chilled. ✓ Fernet-Branca (Italian): A bitter, aromatic blend of approximately 40 herbs and spices (including myrrh, rhubarb, camomile, cardamom, and saffron) in a base of grape alcohol. -

County-Clare-Drink-Menu.Pdf

Draft Bottle Ask for a sample. No refunds Clare Cocktails based on taste preference. Ireland Ireland Magner’s Pear Cider Milwaukee Mule Tango Fizz Guinness Stout Germany Our twist on the Moscow Tequila, mango and Murphy’s Stout Clausthauler Amber N/A Mule: Rehorst Premium club soda Smithwick’s Red Ale Bitburger Drive N/A Vodka, ginger beer with Kilkenny Cream Ale squeeze of fresh lime. Wisconsin Old Harp Lager England Magner’s Cider Fashioned Blackthorn Dry Cider Irish Mule Hand muddled, Wisconsin Irish whiskey, ginger beer style. Choose whiskey or Denmark and lime. Carlsberg Lager Wisconsin brandy. Sweet, sour or with Lakefront New Grist Gluten Free club soda. Belgium Pabst Blue Ribbon Infamous Golfer Grimbergen Dubbel - $7 Miller Lite A wonderfully refreshing Sweet Caroline Coors Light mix of Rehorst Citrus & Irish whiskey, lemonade, Bud Light Honey Premium Vodka, club soda, Chambord. Germany lemonade and iced tea. An Franziskaner New York Arnold Palmer with a kick! Purple Rain England Ommegang Pale Sour Irish Lemonade Vodka, pineapple juice, Fuller’s black currant. Originated here at County American Craft “Work is the Clare: Rehorst Citrus & Bell’s Seasonal Honey Premium Vodka, Milwaukee Breeze curse of the lemonade and a splash of A refreshing cocktail Wisconsin black currant juice. featuring Rehorst Premium Gin, seltzer, cranberry juice Spotted Cow drinking and fresh lime. Third Space Happy Place classes.” Import 20 oz. - $6 ~ Oscar Wilde Domestic Craft - $5 Desserts Ask about our seasonal and rotating taps not listed here. Seasonal Crème Brûlée Delicate seasonally flavored custard with a crispy caramelized sugar topping. Finished with a Specialty Tap dollop of fresh whipped cream. -

Cocktails Non-Alcoholic Drinks Desserts

Non-Alcoholic Drinks Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Sierra Mist Lemonade, Iced Tea $2.50 Orange, Cranberry, Pineapple, Grapefruit, Tomato and Apple $2.50 Herbal Tea $2.50 Black, green, lemon ginger, peppermint, earl grey Cape Foulweather Coffee $2.50 Cocktails Hot Chocolate $3 EISENHOWER Crown Royal, amaretto, house sour, bordeaux cherry $7 Reeds Ginger Ale $3 Henry Weinhard’s Root Beer $3 GOMPERS COLLINS Gompers gin, lemon, sugar, soda water $8 Fever Tree Ginger Beer $4 Fentimans Rose Lemonade $4.50 SAZERAC Bulleit Rye, sugar, bitters, drop of absinthe $9 DUBLIN SIDECAR Jameson, Grand Marnier, lemon juice, bitters, served up $10 PLANTER’S PUNCH Light rum, dark rum, orange juice, lime juice, Desserts dash bitters, splash of grenadine $10 NANCY WHISKEY TRADITIONAL IRISH BREAD PUDDING Kilbeggan Irish Whiskey, Drambuie, Made with Irish whiskey, rum, golden raisins and lemon juice, ginger beer $8 walnuts, topped with fresh whipped cream $6 BRANDY ALEXANDER NANA’S APPLE RASPBERRY DELIGHT Courvoisier, creme de cacao, cream, Baked apples and raspberries with a toasted nutmeg, served up $8 walnut crumble topping, served warm with vanilla ice cream and caramel $6 SPICED APPLE COSMO Absolut Orient Apple, sour apple pucker, CHOCOLATE BRANDY BREAD PUDDING cinnamon whiskey, cranberry juice, served up $9 Served warm, topped with fresh whipped NYE 75 cream and cinnamon $6 Seagram’s gin, Lemoncello, lemon juice, ICE CREAM $4 topped with champagne and served up $9 Optional Toppings: Walnut Crumble $1 MOSCOW MULE Caramel $1 Monopolowa vodka, Choc Syrup $1 Fever Tree -

Cocktail Menu

COCKTAIL MENU The problem with some people is that when they aren’t drunk, they are sober’ William Butler Yeats ALL PRICES INCUR A 15% SERVICE CHARGE (SUBJECT TO VAT) Page 1 DROMOLAND SIGNATURE COCKTAILS DROMOLAND CHAMPAGNE MOJITO e20.50 Rum, Lime Juice, Mint, Simple Syrup and Champagne BITTER SWEET SYMPHONY e20.50 Campari, Grand Marnier, Saint Germain Liqueur, Lemon Juice & Ginger Ale O’BRIEN’S SECRET e30.00 Gentleman Jack, Remy Martin VSOP, Drambuie, Laphroig, Pernod, Angostura Bitters and Orange Bitters WHITE CHOCOLATE MARTINI e21.50 Belvedere Vodka, Crème de Cacao White, Baileys, Frangelico & Cream CELTIC SEA e21.50 Hendrick’s Gin, Blue Curaçao, Cointreau, Lime Juice, Saint Germain Liqueur, Shaken with Cucumber and Served with Tonic Water LOVE STAR MARTINI e21.50 Kalak Vodka, Chambord, Saint Germain Liqueur, Strawberry Puree, Served with a Shot of Prosecco DROMOLAND MAI TAI e22.50 Gold Rum, Triple Sec, Apricot Brandy, Lime Juice, Orange Juice & Pineapple Juice, Served with Dark Rum LADY ETHEL’S WHISPER e21.50 Gold Rum, Mailibu, Red Orange Liqueur, Lime Juice, Cranberry Juice & Pineapple Juice All prices incur a 15% service charge (subject to vat) All prices incur a 15% service charge (subject to vat) Page 2 CHAMPAGNE COCKTAILS CLASSIC CHAMPAGNE COCKTAIL e22.50 Cognac, Angostura Bitters, Simple Syrup & Champagne KIR ROYALE e22.50 Crème de Cassis & Champagne FRENCH 75 e22.50 Gin, Fresh Lemon Juice, Simple Syrup & Champagne GERTIE’S SPECIAL e22.50 Peach Schnapps, Fresh Orange Juice, Cranberry Juice & Champagne SEDUCTION e22.50 Vodka, -

DRINKS Dublin WINTER 2019

COCKTAILS The Ivy Royale flute 14.75 Our signature Kir Royale with rose liqueur, Plymouth Sloe Gin & hibiscus topped with The Ivy Champagne Salted Caramel Espresso Martini coupe 9.75 A classic Espresso Martini made with Absolut Vodka, coffee liqueur and freshly pulled espresso. Sweetened with salted caramel Portobello Spritz wine glass 11.75 Absolut Vodka, Aperol, grapefruit juice, lemon, sugar, soda and Prosecco, finished with rosemary Rhubarb & Raspberry Crumble high-ball 12.50 Fresh raspberries muddled with Ha’penny Rhubarb Gin, Chambord, lemon juice topped with Fever-Tree Ginger Ale Cork Dry Sling high-ball 12.00 A classic Raffles Hotel recipe Singapore Sling but made with Cork Dry Gin. With Cherry Heering, Benedictine, bitters, lime, pineapple & grenadine The Leopold Bloom rocks 11.00 Longueville House Irish apple brandy, Irish Mist liqueur & Cointreau stirred over ice & served in an oak & cinnamon mist Añejo Mojito high-ball 12.00 Packed with flavour, this take on a Mojito combines elderflower, apricot brandy, lime & sugar with Havana 7 year old rum Guns & Rosé coupe 14.95 Drumshanbo Gunpowder Gin, Lillet Rosé Aperitif, Cointreau & maraschino syrup XO Negroni rocks 12.75 A balanced take on the classic that is perfect for the colder months. Patron XO Café, Campari and Antica Formula Vermouth finished with maraschino cherry and orange Chocolate Dipped Raspberry coupe 9.75 Stolichnaya Chocolate & Raspberry vodka, Champbord Black Raspberry Liqueur, pineapple juice, chocolate bitters & fresh raspberries Garden Daiquiri coupe 10.50 A -

Irish Whiskey Menu of Baggot St

of Baggot st Irish Whiskey Menu of Baggot st Welcome to Searsons where we pride ourselves on promoting the best of Irish produce. This commitment is most evident with our approach to our Whiskey Collection. We have over 90 Irish whiskeys in our ever expanding range, most notably of which is the Midleton Very Rare Whiskey Display housing every example of this world famous whiskey from 1984 right up to 2014. You will not come across another collection like this. Alongside all the old favourites you will also find newer entrants to the market, which have challenged the establishment with a level of innovation. Our collection with its diversity of styles, ages, and finishing, holds something for everyone from the connoisseur to the initiate. Let our staff be your guide into the truly magical world that is Irish whiskey! - Sláinte Charlie Chawke 1 IrIsh WhIskey In order to be called an “Irish Whiskey”, distilled spirit must be; - aged in wood barrels for a minimum of 3 years. - a minimum of 40% ABV. - distilled and matured on the island of Ireland. There are several types of Irish Whiskey including; Pot stIll IrIsh WhIskey Pot still whiskey is whiskey made from a combination of malted barley and unmalted barley and is distilled in traditional copper pot stills. Pot Still Irish Whiskeys are characterised by full bodied flavours and a wonderful creamy mouth feel. Blended IrIsh WhIskey A blended whiskey is a combination of 2 or more styles of whiskey (grain, pot still or malt whiskey). GraIn IrIsh WhIskey Grain whiskey is typically produced from a mash of maize and malted barley. -

Whiskey, Liquor, and Spirits

Guide to the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana Subject Categories: Whiskey, Liquor, and Spirits NMAH.AC.0060.S01.01.Whiskey Nicole Blechynden Funding for partial processing of the collection was supported by a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund (CCPF). 2016 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Brand Name Index........................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 13 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 15 Subseries : Business Records and Marketing Material, circa 1774-1964 (bulk 1850-1920)............................................................................................................. -

Massachusetts

MASSACHUSETTS NORTON OFFICE LUDLOW OFFICE 45 Commerce Way 485 Holyoke Street Norton, MA 02766 Ludlow, MA 01056 508-587-1110 508-587-1110 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to Horizon Beverage! ..................................................1 Spirits & Beer .........................................................................2-5 Local Producers ..............................................................2 Beer, Cider & Hard Seltzers ..............................................3 Spirits ...........................................................................4-5 Origin Beverage ..............................................................6 Bottled Cocktails .............................................................7 Wine ......................................................................................8-15 Signature Wine Sales Team ..............................................10 Trellis Fine Wine Sales Team .............................................11 Cans & Kegs ...................................................................12 Looking for Sparkling Options? .........................................13 Thinking about Sangria? ..................................................14 Cooking Wine & Single Serve ............................................15 Non-Alcoholic Options ..............................................................16 Italian Spirits, Wine & Beer .......................................................17-19 Opening a Mexican Restaurant? .................................................20 Opening a Restaurant -

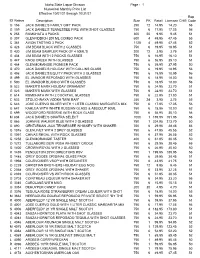

Description Idaho State Liquor Division Numerical Monthly Price

Idaho State Liquor Division Page : 1 Numerical Monthly Price List Effective 10/01/21 through 10/31/21 Rep ID Nabca Description Size PK Retail Licensee CHG Code G 156 JACK DANIEL'S FAMILY GIFT PACK 250 12 14.95 14.20 56 G 159 JACK DANIEL'S TENNESSEE FIRE WITH SHOT GLASSES 750 6 17.95 17.05 56 N 258 RUMCHATA 3 PACKS 300 20 9.95 9.45 51 G 307 GLENFIDDICH 200 ML COMBO PACK 600 4 49.95 47.45 55 C 381 AVION TASTING 3 PACK 1125 4 49.95 47.45 52 G 428 JIM BEAM BLACK WITH 2 GLASSES 750 6 19.95 18.95 51 G 430 JIM BEAM SAMPLER PACK OF 4 50ML'S 200 12 3.95 3.75 51 G 434 JIM BEAM WITH 2 ROCKS GLASSES 750 6 16.95 16.10 51 G 447 KNOB CREEK WITH GLASSES 750 6 36.95 35.10 51 G 464 GLENMORANGIE PIONEER PACK 750 6 39.95 37.95 50 G 470 JACK DANIEL'S HOLIDAY WITH COLLINS GLASS 750 6 19.95 18.95 56 G 498 JACK DANIEL'S EQUITY PACK WITH 2 GLASSES 750 6 19.95 18.95 56 G 499 EL JIMADOR REPOSADO WITH GLASSES 750 6 18.95 18.00 56 C 500 EL JIMADOR BLANCO WITH GLASSES 750 6 18.95 18.00 56 G 522 MAKER'S MARK HOLIDAY ORNAMENT 750 6 24.95 23.70 51 G 525 MAKER'S MARK WITH GLASSES 750 6 24.95 23.70 51 C 614 RUMCHATA WITH 2 COCKTAIL GLASSES 750 6 22.95 21.80 51 C 633 STOLICHNAYA VODKA "MINI BAR" 250 24 3.95 3.75 55 G 643 JOSE CUERVO SILVER WITH 1 LITER CLASSIC MARGARITA MIX 750 6 17.95 17.05 56 G 647 KAHLUA WITH WHITE RUSSIAN GLASS & ABSOLUT 50ML 750 6 18.95 18.00 52 G 699 WOODFORD RESERVE WITH ROCK GLASS 750 6 36.95 35.10 56 M 804 JACK DANIEL'S SINATRA SELECT 1000 1 159.95 151.95 56 G 866 JOHNNIE WALKER BLUE WITH 2 GLASSES 750 1 224.95 213.70 50 G 890 GENTLEMAN JACK TENNESSEE