How to Make Rubber Jewelry Molds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investment Casting Or the Lost Wax Process

Investment Casting or The Lost Wax Process Apecs Investment Castings was founded in 1963 and is now situated in the Melbourne suburb of Burwood where we have been since we outgrew our Canterbury factory in August 1987. The company name (APECS), stands for Anthony Philip Eccles Casting Service. Investment is a type of plaster that we use in our process of reproducing multiple copies of an original master pattern which is usually supplied to us by our customers. This is a classic 18ct yellow gold emerald and diamond ring taken from the Apecs catalogue. The next series of photos will show the steps involved in producing multiple copies of this ring. An original master pattern is designed and fabricated by our customers and supplied to us to reproduce in the quantities and metals of their choice. It is important to ensure that the master is made as accurately as possible and to pay particular attention to the finish of the master pattern. The better the quality of the master pattern the better the casting result. The finished master pattern ready for the caster. A picture of the master pattern is drawn and a mould number is allocated for identification. When the customer wants to reorder he quotes the mould number for the pattern he wants. A sprue is soldered onto the pattern. This sprue enables the pattern to be easily located in the mould and will provide the path for the wax to be injected into the rubber mould. To make a mould the master pattern is placed between sheets of uncured vulcanising rubber. -

The Lost-Wax Casting Process—Down to Basics by Eddie Bell, Founder, Santa Fe Symposium

The Lost-Wax Casting Process—Down To Basics By Eddie Bell, Founder, Santa Fe Symposium. Lost-wax casting is a ancient technique that is used today in essentially the same manner as it was first used more than 5,000 years ago. As they say, there's no messing with success. Today, of course, technology has vastly expanded the technique and produced powerful equipment that makes the process faster, easier and more productive than ever, but the basic steps remain the same. The steps below represent a simple overview and are intended to provide a beginning understanding of the casting process. Concept This is obviously where the design is initally conceived, discussed,evolved, and captured on paper—or on computer; CAD (computer aided design) software is increasingly popular among designers. You create the design you envision using the computer tool and the software creates a file that can be uploaded into a CNC mill or 3D printer. Model Build a model, either by hand-carving, guided by the paper rendering, or by uploading the CAD file into a computer controlled milling machine or a 3D printing machine. Models are made using carving wax, resin or similar material. This process can also be done in metal by a goldsmith or silversmith. Note: If a 3D printer or other rapid prototyping equipment is used, it is possible to skip the molding and wax-injection steps by using one of the resins that are specially made to go directly to the treeing process. Molding Create a mold from your master model, placing it in one of a variety of rubber or silicone materials, curing the material, then removing the model from the finished mold. -

St Luke's Farnworth BELL CASTING

St Luke’s Farnworth BELL CASTING by Geoffrey Poole In the earliest days they were cast in different sizes to produce different notes but no attempt was made to tune bells until the 16th Century with the advent of change ringing. In those times bells were roughly tuned – where the inside of the bell or the edge of the lip was chipped away with a hammer and chisel – eight bells could be tuned to an octave of eight notes. Some deprived communities used a hagiosideron, a shaped piece of metal which was struck in a similar way to a bell. Also again due to lack of money bellcotes were used instead of costly towers. A bell-cot, bell-cote or bellcote is a small framework and shelter for one or more bells. Bellcotes are most common in church architecture but are also seen on institutions such as schools. The bellcote may be carried on brackets projecting from a wall or built on the roof of chapels or churches that have no towers. The bellcote often holds the Sanctus bell that is rung at the consecration of the Eucharist. Bellcote is a compound noun of the words bell and cot or cote. Bell is self-explanatory. The word cot or cote is Old English, from the Germanic. It means a shelter of some kind, especially for birds or animals (see dovecote), a shed, or stall. Examples of bellcotes In order St Luke’s Farnworth Bell-cot at St Edmund's Church, Church Road, Wootton, Isle of Wight, England Church of England parish church of St Alban the Martyr, CharlesStreet, Oxford. -

Influence of High-Temperature Treatment of Melt on the Composition and Structure of Aluminum Alloy

ARCHIVES of ISSN (2299-2944) FOUNDRY ENGINEERING Volume 17 DOI: 10.1515/afe-2017-0131 Issue 4/2017 Published quarterly as the organ of the Foundry Commission of the Polish Academy of Sciences 61 – 66 Influence of High-Temperature Treatment of Melt on the Composition and Structure of Aluminum Alloy V.A. Grachev a, *, N.D. Turakhodjaev b a A.N. Frumkin Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 29 Bldg 1, Bolshaya Ordynka St., Suite # 104, 119017 Moscow, Russia b Tashkent State Technical University, Faculty of Mechanical University 2,Tashkent 100095, Republic of Uzbekistan, * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] Received 12.04.2017; accepted in revised form 23.06.2017 Abstract The aim of the current study was to examine the structure of an alloy treated at various temperatures up to 2,000–2,100 °C. Among research techniques for studying alloy structure there were the electron and optical microstructure, X-ray structure, and spectral analysis, and for studying the developed furnace geometric parameters the authors employed mathematical modeling method. The research was performed using aluminum smelting gas-fired furnaces and electric arc furnaces. The objects of the study were aluminum alloys of the brand AK7p and AK6, as well as hydrogen and aluminum oxide in the melt. For determining the hydrogen content in the aluminum alloy, the vacuum extraction method was selected. Authors have established that treatment of molten aluminum alloy in contact with carbon melt at high temperatures of 2,000–2,100 °C has resulted in facilitating reduction of hydrogen and aluminum oxide content in the melt by 40- 43% and 50-58%, respectively, which is important because hydrogen and aluminum oxide adversely affect the structure and properties of the alloy. -

Metal Casting Terms and Definitions

Metal Casting Terms and Definitions Table of Contents A .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 B .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 C .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 D .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 E .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 F ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 G .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 H .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 I .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Etch Overview for Microsystems Learning Module

EEttcchh OOvveerrvviieeww ffoorr MMiiccrroossyysstteemmss Learning Module Map Knowledge Probe Etch Overview Activities (3) Final Assessments Instructor Guide www.scme-nm.org What is a SCO? A SCO is a "shareable-content object" or, what we like to call, a "self-contained object". The term SCO comes from the Shareable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM), first conceived by the Department of Defense in 1999 as part of the Advanced Distributed Learning Initiative (Gonzales, 2005; Advanced Distributed Learning, 2008). A SCO covers no more than 3 objectives that pertain to one specific topic (e.g., Material Safety Data Sheets or MEMS Applications). A SCO can be used by itself or with other SCOs with common or complementary objectives. We have grouped SCOs that support common objectives into a Learning Module. Learning Module Organization Each Learning Module (LM) contains at least one of the following three types of SCOs: Primary Knowledge (PK) - Each LM contains at least one PK which contains the basic information supporting the objectives. Most PKs have a supporting PowerPoint presentation. Activity (AC) – Each LM can contain one or more activities that provide interactive or hands-on learning that supports the objectives. Assessment (KP, FA, AA) – Each LM contains one or more assessments that determines the student's existing knowledge (Knowledge Probe (KP) or pretest) or knowledge gained relative to a particular AC, the PK or both. (Activity Assessment (AA), Final Assessment (FA)). Each SCO contains an Instructor Guide (IG) and Participant Guide (PG). Each SCO is self-contained; therefore any one SCO in the Learning Module can be used without the other SCOs, depending upon the needs of the student and the instructor. -

40 CFR Ch. I (7–1–14 Edition) Pt. 300, App. B

Pt. 300, App. B 40 CFR Ch. I (7–1–14 Edition) gamma-emitting radionuclides in surface and nonradioactive hazardous substances materials. separately. Compare the concentration of Select the benchmark(s) applicable to the each radionuclide and each nonradioactive pathway (or threat) being evaluated. Com- hazardous substance from the sampling loca- pare the concentration of each radionuclide tion to its respective benchmark concentra- from the sampling location to its benchmark tion(s). Use only those samples and only concentration(s) for that pathway (or those substances in the sample that meet the threat). Use only those samples and only criteria for an observed release (or observed those radionuclides in the sample that meet contamination) for the pathway except: tis- the criteria for an observed release (or ob- sue samples from aquatic human food chain served contamination) for the pathway, ex- organisms may be used as specified in sec- cept: tissue samples from aquatic human tions 4.1.3.3 and 4.2.3.3. If the concentration food chain organisms may be used as speci- of one or more applicable radionuclides or fied in sections 4.1.3.3 and 4.2.3.3. If the con- other hazardous substances from any sample centration of any applicable radionuclide equals or exceeds its benchmark concentra- from any sample equals or exceeds its bench- tion, consider the sampling location to be mark concentration, consider the sampling subject to Level I concentrations. If more location to be subject to Level I concentra- than one benchmark applies to a radio- tions for that pathway (or threat). -

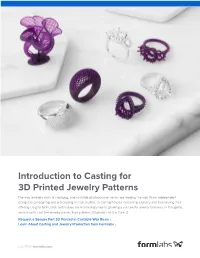

Introduction to Casting for 3D Printed Jewelry Patterns the Way Jewelers Work Is Changing, and Castable Photopolymer Resins Are Leading the Way

Introduction to Casting for 3D Printed Jewelry Patterns The way jewelers work is changing, and castable photopolymer resins are leading the way. From independent designers concepting and prototyping in their studios, to casting houses increasing capacity and diversifying their offerings, digital fabrication techniques are increasingly key to growing a successful jewelry business. In this guide, learn how to cast fine jewelry pieces from patterns 3D printed on the Form 2. Request a Sample Part 3D Printed in Castable Wax Resin › Learn About Casting and Jewelry Production from Formlabs › July 2019 | formlabs.com What Is Direct Investment Casting? Direct investment casting, or lost wax casting, is a popular moldmaking technique that can be used to fabricate small and large parts in a wide variety of metals. Originating over 5,000 years ago, casting enables creators to work with a wide variety of materials and is one of the easiest ways to make metal parts. In investment casting, a hollow mold is created from a hand-sculpted or 3D printed master pattern. The master is immersed in a refractory casting material (or “investment”), which dries and hardens. The wax or 3D printed pattern is burned out, leaving a negative mold of the design. Metal is poured into this hollow cavity to create the final part. Wax patterns for intricate jewelry are complicated to produce by hand, and in a world driven by high demand and fast fashion, it can be difficult for hand-crafted pieces to keep pace. Advanced materials and affordable in-house 3D printers like the Form 2 are changing the way jewelry manufacturers and designers work, bringing industrial quality to the desktop and making it easier to produce and fit complicated geometries that once required hours of meticulous labor. -

Emerging Technologies in Metal Working Fluids and Compatibility with Refrigeration Systems Richard Butler [email protected]

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning School of Mechanical Engineering Conference 2016 Emerging Technologies in Metal Working Fluids and Compatibility with Refrigeration Systems Richard Butler [email protected] Mike Foster [email protected] Neil Turner CPI Fluid Engineering, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc Butler, Richard; Foster, Mike; and Turner, Neil, "Emerging Technologies in Metal Working Fluids and Compatibility with Refrigeration Systems" (2016). International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. Paper 1617. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc/1617 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Complete proceedings may be acquired in print and on CD-ROM directly from the Ray W. Herrick Laboratories at https://engineering.purdue.edu/ Herrick/Events/orderlit.html 2127, Page 1 Emerging Technologies in Metal Working Fluids and Compatibility with Refrigeration Systems International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference at Purdue 2016 Richard Butler1*, Neil Turner2, Nicholas Bujouves3 1Chemtool, Inc., R&D Laboratory, Rockton, Illinois, U.S.A. ([email protected]) 2CPI Fluid Engineering, R&D Laboratory, Midland, Michigan, U.S.A. ([email protected]) 3CPI Fluid Engineering, R&D Laboratory, Midland, Michigan, U.S.A. ([email protected]) * Corresponding Author ABSTRACT Metal working fluids (MWF) are basically two types, metal removal (chip making) and metal forming (chip-less). MWF are used in all aspects of production fabrication of refrigeration systems. Metal removal applications typically include turning followed by finish lapping of crankshafts and piston connecting rods, also milling and finish grinding of screw compressor vanes. -

Introduction to Casting for 3D Printed Jewelry Patterns

Introduction to Casting for 3D Printed Jewelry Patterns The way jewelers work is changing, and castable photopolymer resins are leading the way. From independent designers concepting and prototyping in their studios, to casting houses increasing capacity and diversifying their offerings, digital fabrication techniques are increasingly key to growing a successful jewelry business. In this guide, learn how to cast fine jewelry pieces from patterns 3D printed on the Form 3. Request a Sample Part 3D Printed in Castable Wax Resin › Learn About Casting and Jewelry Production from Formlabs › July 2019 | formlabs.com What Is Direct Investment Casting? Direct investment casting, or lost wax casting, is a popular moldmaking technique that can be used to fabricate small and large parts in a wide variety of metals. Originating over 5,000 years ago, casting enables creators to work with a wide variety of materials and is one of the easiest ways to make metal parts. In investment casting, a hollow mold is created from a hand-sculpted or 3D printed master pattern. The master is immersed in a refractory casting material (or “investment”), which dries and hardens. The wax or 3D printed pattern is burned out, leaving a negative mold of the design. Metal is poured into this hollow cavity to create the final part. Wax patterns for intricate jewelry are complicated to produce by hand, and in a world driven by high demand and fast fashion, it can be difficult for hand-crafted pieces to keep pace. Advanced materials and affordable in-house 3D printers like the Form 2 are changing the way jewelry manufacturers and designers work, bringing industrial quality to the desktop and making it easier to produce and fit complicated geometries that once required hours of meticulous labor. -

A Study of Metal Founding and Its Practices and Applications for Information Purposes in Industrial Arts Education

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 1-1-1965 A Study of Metal Founding and its Practices and Applications for Information Purposes in Industrial Arts Education Jack Fuelle Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Fuelle, Jack, "A Study of Metal Founding and its Practices and Applications for Information Purposes in Industrial Arts Education" (1965). Plan B Papers. 418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/418 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A S'11UDY O:J:t"' NLE'rAL :B'OUNDING AND I'l1 S PRAC'rICES AND APPLICATIONS FOR INFOHMA'EION PURPOSES IN IlIDUSTHIAL At{rS ELJUUATION (TITLE) BY JacK .1melle PLAN B PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE industrial Arts J75 IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. ----~'7fa6,ls ---~--~---- -~-~~- DATE ADVISER TABLE OF CONTENTS Chaplier Page I INTRODUCTION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1 Purpose Signiricance or tne Stua.y 'I'er.m.1no.logy II BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FOUNDHY ••••••••••••••••• b Ear.Lies1i Beginnings 5000 B. C• .lbOO B. C. Weapons in Ea:c.Ly Found.1.·y Work Guns.miths in Early Foundry Work Current Developments in Founding III FOUNDRY EQ,U.1Pl~'l'. -

Aluminum Foundry Products

ASM Handbook, Volume 2: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials Copyright © 1990 ASM International® ASM Handbook Committee, p 123-151 All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1361/asmhba0001061 www.asminternational.org Aluminum Foundry Products Revised by A. Kearney, Avery Kearney & Company Elwin L. Rooy, Aluminum Company of America ALUMINUM CASTING ALLOYS are wrought alloys. Aluminum casting alloys cast aluminum alloys are grouped according the most versatile of all common foundry must contain, in addition to strengthening to composition limits registered with the alloys and generally have the highest cast- elements, sufficient amounts of eutectic- Aluminum Association (see Table 3 in the ability ratings. As casting materials, alumi- forming elements (usually silicon) in order article "Alloy and Temper Designation Sys- num alloys have the following favorable to have adequate fluidity to feed the shrink- tems for Aluminum and Aluminum Al- characteristics: age that occurs in all but the simplest cast- loys"). Comprehensive listings are also • Good fluidity for filling thin sections ings. maintained by general procurement specifi- The phase behavior of aluminum-silicon • Low melting point relative to those re- cations issued through government agencies compositions (Fig. 1) provides a simple quired for many other metals (federal, military, and so on) and by techni- • Rapid heat transfer from the molten alu- eutectic-forming system, which makes pos- cal societies such as the American Society sible the commercial viability of most high- minum to the mold, providing shorter for Testing and Materials and the Society of casting cycles volume aluminum casting. Silicon contents, Automotive Engineers (see Table 1 for ex- • Hydrogen is the only gas with apprecia- ranging from about 4% to the eutectic level amples).