Hist-Lowell Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Porcellian Club Centennial, 1791-1891

nia LIBRARY UNIVERSITY W CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO NEW CLUB HOUSE PORCELLIAN CLUB CENTENNIAL 17911891 CAMBRIDGE printed at ttjr itttirnsiac press 1891 PREFATORY THE new building which, at the meeting held in Febru- ary, 1890, it was decided to erect has been completed, and is now occupied by the Club. During the period of con- struction, temporary quarters were secured at 414 Harvard Street. The new building stands upon the site of the old building which the Club had occupied since the year 1833. In order to celebrate in an appropriate manner the comple- tion of the work and the Centennial Anniversary of the Founding of the Porcellian Club, a committee, consisting of the Building Committee and the officers of the Club, was chosen. February 21, 1891, was selected as the date, and it was decided to have the Annual Meeting and certain Literary Exercises commemorative of the occasion precede the Dinner. The Committee has prepared this volume con- taining the Literary Exercises, a brief account of the Din- ner, and a catalogue of the members of the Club to date. A full account of the Annual Meeting and the Dinner may be found in the Club records. The thanks of the Committee and of the Club are due to Brothers Honorary Sargent, Isham, and Chapman for their contribution towards the success of the Exercises Literary ; also to Brother Honorary Hazeltine for his interest in pre- PREFATORY paring the plates for the memorial programme; also to Brother Honorary Painter for revising the Club Catalogue. GEO. B. SHATTUCK, '63, F. R. APPLETON, '75, R. -

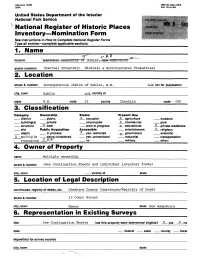

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Civil War Fought for the Union Which Represent 52% of the Sons of Harvard Killed in Action During This Conflict

Advocates for Harvard ROTC . H CRIMSON UNION ARMY VETERANS Total served Died in service Killed in action Died by disease Harvard College grads 475 73 69 26 Harvard College- non grads 114 22 Harvard Graduate schools 349 22 NA NA Total 938 117 69 26 The above total of Harvard alumni who died in the service of the Union included 5 major generals, 3 Brigadier Generals, 6 colonels, 19 LT Colonels and majors, 17 junior officers in the Army, 3 sergeants plus 3 Naval officers, including 2 Medical doctors. 72% of all Harvard alumni who served in the Civil War fought for the Union which represent 52% of the sons of Harvard killed in action during this conflict. As result among Harvard alumni, Union military losses were 10% compared with a 21% casualty rate for the Confederate Army. The battle of Gettysburg (PA) had the highest amount of Harvard alumni serving in the Union Army who were killed in action (i.e. 11), in addition 3 Harvard alumni Confederates also died in this battle. Secondly, seven Crimson warriors made the supreme sacrifice for the Union at Antietam (MD) with 5 more were killed in the battles of Cedar Mountain (VA) and Fredericksburg (VA). As expected, most of the Harvard alumni who died in the service of the Union were born and raised in the Northeastern states (e.g. 74% from Massachusetts). However, 9 Harvard alumni Union casualties were from the Mid West including one from the border state of Missouri. None of these Harvard men were from southern states. The below men who made the supreme sacrifice for their country to preserve the union which also resulted in the abolition of slavery. -

“The Wisest Radical of All”: Reelection (September-November, 1864)

Chapter Thirty-four “The Wisest Radical of All”: Reelection (September-November, 1864) The political tide began turning on August 29 when the Democratic national convention met in Chicago, where Peace Democrats were unwilling to remain in the background. Lincoln had accurately predicted that the delegates “must nominate a Peace Democrat on a war platform, or a War Democrat on a peace platform; and I personally can’t say that I care much which they do.”1 The convention took the latter course, nominating George McClellan for president and adopting a platform which declared the war “four years of failure” and demanded that “immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the states, or other peaceable means, to the end that, at the earliest practicable moment, peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal Union of the States.” This “peace plank,” the handiwork of Clement L. Vallandigham, implicitly rejected Lincoln’s Niagara Manifesto; the Democrats would require only union as a condition for peace, whereas the Republicans insisted on union and emancipation. The platform also called for the restoration of “the rights of the States 1 Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, ed. Herbert Mitgang (1895; Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1971), 164. 3726 Michael Burlingame – Abraham Lincoln: A Life – Vol. 2, Chapter 34 unimpaired,” which implied the preservation of slavery.2 As McClellan’s running mate, the delegates chose Ohio Congressman George Pendleton, a thoroughgoing opponent of the war who had voted against supplies for the army. As the nation waited day after day to see how McClellan would react, Lincoln wittily opined that Little Mac “must be intrenching.” More seriously, he added that the general “doesn’t know yet whether he will accept or decline. -

T Camp Meigs, READVILLE, M.VM MASS

CIVIL WAR CAMPS AT READVILLE CAMP MEIGS PLAYGROUND & FOWL MEADOW RESERVATION VoL. PRELIMINARY HISTORIC DATA COMPILATION Cant oF t Camp Meigs, READVILLE, M.VM MASS. Sr 0 47c r i )1; CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROGRANI W. A. Stokinger A. K. Schroeder Captain A. A. Swanson RESERVATIONS & HISTORIC SITES METROPOLITAN DISTRICT COMMISSION 20 SOMERSET STREET BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS April 1990 ABSTRACT Camp Meigs or the Camp at Readville was the most heavily used of the approximately thirty-nine Civil War training grounds established by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the processing of Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (MVM) troops for induction into Federal service. Situated adjacent to the Neponset river on a site historically used for militia musters in what was the town of Dedham (now Hyde Park), a camp of rendezvous was first founded near the Readville railroad junction in July 1861 and remained in active service through early 1866. This camp supported over time the Commonwealth's primary training cantonment and a general hospital. During those Civil War years the Readville camps processed and trained at least 29,000 of the 114,000 men who served in the units raised by the Commonwealth. Thus, approximately a quarter of all men serving under Massachusetts state colors passed through Readville on their way to war. Preliminary research also indicates that of the 135 discrete, independently operating MVM organizations sanctioned and trained by the Commonwealth, Readville's graduates were allocated into at least 54 units, or forty percent of all MVM establishments, comprising: Nineteen of the Commonwealth's sixty-six camp trained MVM Infantry regiments. -

Seventh Generation

Seventh Generation The seventh generation descendants of Richard include quite a few notable individuals. Samuel P May was not a descendant but was married to two Sears sisters(Nos. 2804 & 2808) and wrote the definitive work on Richard Sears' genealogy. This volume would not be possible without his remarkable efforts. Rev Edmund H Sears is a well known theologian and author of the words to "It Came Upon a Midnight Clear." He also wrote the first Sears Genealogy which was pointed out to contain many errors by Dr May. The Sears' Family Tree is based on Edmund's work and was created by Olive Sears(No. 2222). Sea captains abound and are the subject of many of May's anecdotes. Capt Joshua (No. 2516) the clipper ship captain and Capt Dean (No.2465) a packet captain are just two of the more well known seafarers. The sequence numbers of this generation range from No. 1811 to No. 3590. Their birth dates begin in 1774 (No. 1852) and go to 1856 (No. 3418). There are over 600 individuals with recorded children carried forward from the last generation. May had about 300 families in his seventh generation and we now list about 450 families with surname Sears. Children of this generation number 2200 and were born between 1800-1899. The largest families have 13 children (Nos. 2121, 3181, 3496). Two of the children from this generation have no recorded offspring and are not carried forward to the next chapter but should be noted. Jacob Sears (No.4325) is known for his philanthropy and the Jacob Sears Memorial Library in E Dennis, MA and Clara Endicott Sears (No. -

Hero Tales from American History ROOSEVELT Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt Hero Tales from American History Courage Under Fire

LODGE hero tales from american history ROOSEVELT henry cabot lodge and theodore roosevelt hero tales from american history Courage under Fire. Self-Sacrifice. Battles that Changed America. American history is full of men and women who have acted courageously when their families, communities and country needed them most. Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt discovered they both loved telling the stories of these outstanding individuals who helped make America. They pared down their favorite stories to 26 and gave them as a gift to the young people of America in 1895. The McConnell Center is pleased to make this volume available again to America’s youth in hopes that it inspires them to learn more of our history and encourages them to new acts of heroism. Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) served in the United States Senate from 1893 until his death in 1924. He was one of the most important American statesmen of the early 20th century and was leader of the Republican Party in the Senate. Among the books he authored were important biographies of George Washington, Daniel Webster and Alexander Hamilton. Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) was the 26th president of the United States. He authored more than 18 books, won the Nobel Peace Prize and accomplished enough to earn his place alongside George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson on Mount Rushmore, our most recognized monument to American political heroes. McConnell Center LITTLE BOOKS BIG IDEAS www.mcconnellcenter.org INTRODUCTION BY U.S. SENATOR MITCH MCCONNELL LITTLE BOOKS BIG IDEAS AND GARY L. GREGG II henry cabot lodge and theodore roosevelt heroHERO talesTALES fromfrom AMERICAN americanHISTORY history Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt INTRODUCTION BY U.S. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 76, 1956-1957

Ha G. / i.] BOSTON SYMPHONY OR.CHE STRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON -7 f 'mm X a^b- m. iilMliiiill rf4 ~pFlj^ \ SEVENTY-SIXTH SEASON i95 6 - x 957 Sunday Afternoon Series BAYARD TUCKERMAN. JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON. JR. HERBERT S. TUCKERMAN J. DEANE SOMERVILLE It takes only seconds for accidents to occur that damage or destroy property. It takes only a few minutes to develop a complete insurance program that will give you proper coverages in adequate amounts. It might be well for you to spend a little time with us helping to see that in the event of a loss you will find yourself protected with insurance. WHAT TIME to ask for help? Any time! Now! CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. CHARLES H. WATKINS RICHARD P. NYQUIST in association with OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mass. LA fayette 3-5700 SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SEVENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1956-1957 8 CONCERT BULLETIN of the 4\ Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Rich\rd Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the Inc. BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, c-cr Henry B. Cabot President UUL — Jacob Kaplan Vice-President J. A° Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks, Jr. E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Theodore P. Ferris Michael T. Kelleher Alvan T. Fuller Palfrey Perkins Francis W. Hatch Charles H. Stockton Harold D. Hodgkinson ^DWARD A. TaFT*^ C. D. Jackson Raymond 5. -

The Nature of Sacrifice:A Biography of Charles Russell Lowell, Jr

Civil War Book Review Summer 2005 Article 20 The Nature of Sacrifice:A Biography of Charles Russell Lowell, Jr. Richard F. Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Miller, Richard F. (2005) "The Nature of Sacrifice:A Biography of Charles Russell Lowell, Jr.," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol7/iss3/20 Miller: The Nature of Sacrifice:A Biography of Charles Russell Lowell, Jr Review Miller, Richard F. Summer 2005 Bundy, Carol The Nature of Sacrifice:A Biography of Charles Russell Lowell, Jr.. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30.00 hardcover ISBN 374120773 Gentleman soldier The real story behind the eulogized Yankee The South lost its cause and its men; a victorious North lost only men. For some Northerners however, not all losses were equal. Some deaths left larger legacies, usually by virtue of high birth, membership in families that could afford to publish posthumous memorials, or who boasted connections with the era's literati. Farmers, mechanics, and Harvard men had all streamed to the colors in 1861 and many did not return. But it is the Harvardians who have come down to us in Memorial Hall's stained glass windows, eulogized in the Harvard Memorial Biographies and often celebrated in poetry by Ralph Waldo Emerson, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., and Herman Melville. In the half century after Appomattox this warrior-elite was further embedded in the national consciousness by living memorials such as William Francis Bartlett, in celebrated speeches by the likes (if not the very life) of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 74, 1954-1955

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIG SEVENTY-FOURTH SEASON !954-i955 Tuesday Evening Series BAYARD TUC3LERMAN, JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON RORERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON. JR. HERBERT S. TUGKERIIAH We blueprint the basic structure for the insur- ance of our clients and build their protection on a sound foundation. Only by a complete survey of needg, followed by intelligent counsel, can a proper insurance program be constructed. We shall be glad to act as your insurance architects. Please call us at any time. OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mass. LAfayette 3-5700 SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON Telephone, Commonwealth 6-1492 SEVENTY-FOURTH SEASON, 1954-1955 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot . President Jacob J. Kaplan . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Talcott M. Banks, Jr. C. D. Jackson John Nicholas Brown Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Palfrey Perkins Alvan T. Fuller Charles H. Stockton Francis W. Hatch Edward A. Taft Harold D. Hodgkinson Raymond S. Wilkins Oliver Wolcott . TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howr N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager ) Assistant G. W. Rector J. J. Brosnahan, Assistant Treasurer N. S. Shirk ) Managers Rosario Mazzeo, Personnel Manager CO THE LIVING TRUST How It Benefits You, Your Family, Your Estate Unsettled conditions . new inventions . political changes . , interest rates and taxes, today make the complicated field of in- vestments more and more a province for specialists. -

History of the Twelfth Massachusetts Volunteers (Webster Regiment)

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com HistoryoftheTwelfthMassachusettsvolunteers(Websterregiment) BenjaminF.Cook,JamesBeale wi.^m^^ .^■^M t i HISTORY OF THE TWELFTH MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEERS {WEBSTER REGIMENT) BY LIEUTENANT-COLONEL BENJAMIN F. COOK PUBLISHED BY THE TWELFTH (WEBSTER) REGIMENT ASSOCIATION Boston: 1882 E 5 IS . 5 ([ PBEFAOE. ! 1 4 T the annual re-union Jof the survivors of the Twelfth (Web- ster) Regiment in August, 1879, it was voted to have a full and complete history of jthe regiment written. To that end an Historical Committee was chosen, consisting of five members of the Association ; and the duty of selecting an historian was dele gated to it. Subsequently the committee made choice of the undersigned. For the honor conferred upon me I heartily thank my comrades, although I think that their choice might have been better placed. Th^re are many in the regiment more competent to perform the duty than myself; yet I can say, however, that I believe there is no one more earnestly desirous that the story of the great trials, hardships, and almost unexampled heroism of those three eventful j*ears from 1861 to '64 shall be told to the public of to-day and succeeding generations. Neither is there one more anxious that justice be done to each and every member of the regiment. In commencing my work, I issued a circular, asking the assist ance of comrades, and also calling for diaries, memoranda, and material of any kind, from which to construct my story. -

Book ^ Life and Letters of Charles Russell Lowell > Read

RYAPOIYPAE « Life and Letters of Charles Russell Lowell / Doc Life and Letters of Ch arles Russell Lowell By Edward Waldo Emerson University of South Carolina Press. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 554 pages. Dimensions: 7.9in. x 5.0in. x 1.4in.First published in 1907, Life and Letters of Charles Russell Lowell presents the biography and collected correspondence of the nephew of poet and abolitionist leader James Russell Lowell. The volume spans both the younger Lowells collegiate education and his military service in the American Civil War. A native Bostonian, Charles Russell Lowell (1835-1864) was first in the Harvard class of 1854. He joined the Union ranks a fervent abolitionist and fought with near-reckless zeal until his death in battle at Cedar Creek, Virginia, in October 1864. Lowell served on Gen. George B. McClellans staff in 1862, fought John S. Mosbys Confederate raiders in 1863 and 1864, and participated in the 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaign as cavalry brigade commander. This first paperback edition of Lowells biography and correspondence is supplemented by an introduction by Joan Waugh in which she investigates the connection between Lowells values and actions. Her examination of the inherent sense of duty demonstrated by Lowell, his family, and fellows offers a distinctively Boston Brahmin answer to why young men of the North and South took up arms and went to war.... READ ONLINE [ 2.13 MB ] Reviews This sort of pdf is everything and got me to searching forward and a lot more. Of course, it is engage in, nevertheless an interesting and amazing literature.