Historic Resource Study: Short Hill Tract, Harpers Ferry National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Branch Patapsco River Watershed Characterization Plan

South Branch Patapsco River Watershed Characterization Plan Spring 2016 Prepared by Carroll County Bureau of Resource Management South Branch Patapsco Watershed Characterization Plan Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iv List of Appendices .......................................................................................................................... v List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... vi I. Characterization Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 A. Purpose of the Characterization ....................................................................................... 1 B. Location and Scale of Analysis ........................................................................................ 1 C. Report Organization ......................................................................................................... 3 II. Natural Characteristics ............................................................................................................ 5 A. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

![Nomination Form, 1983]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3443/nomination-form-1983-43443.webp)

Nomination Form, 1983]

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) VvvL ~Jtf;/~ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service !VfH-f G"/;<-f/q NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ============================================================================================== 1. Name of Property ============================================================================================== historic name Bear's Den Rural Historic District other names/site number VDHR File No. 021-6010 ============================================================================================== 2. Location ============================================================================================== street & number Generally runs along both sides of ridge along parts of Raven Rocks and Blue Ridge Mtn Rds, extends down Harry -

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

History of Roads in Fairfax County, Virginia from 1608

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. A HISTORY OF ROADS IN FAIRFAX COUNTY, VIRGINIA: 1608-1840 by Heather K. Crowl submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Anthropology Chair: Richard J. -

Blue Ridge Anticlinorium in Central Virginia

VILLARD S. GRIFFIN, JR. Department of Chemistry and Geology, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29631 Fabric Relationships Across the Catoctin Mountain- Blue Ridge Anticlinorium in Central Virginia ABSTRACT a subhorizontal northeast-bearing lineation. A diagram of poles to mica cleavages defines Study of planar and linear subfabrics across a subfabric characterized by a complete girdle the Catoctin Mountain-Blue Ridge anticlin- similar to the s-pole T-girdle, but having a orium in central Virginia suggests distinct /3 pole bearing 17 degrees closer to due north. differences in the kinematic history of the The Catoctin Mountain-Blue Ridge anti- core and flanks of the anticlinorium. The clinorium in central Virginia is similar to its Precambrian basement complex gneisses in extension in Maryland and Pennsylvania and the core of the anticlinorium record the possesses the same cleavage and foliation fan effects of penetrative deformation in the a evident in the anticlinorium there. The anti- direction. Maxima of mica cleavage poles clinorium in central Virginia, however, has form a complete girdle subnormal to the fewer similarities with the Grandfather pronounced down-dip lineation of elongated Mountain Window area southwestward in minerals. Northeast-striking foliation pro- North Carolina. Like the rocks in the Window duces well-defined maxima that have a poorly area, the Precambrian basement rocks in the developed partial ir-girdle. anticlinorium are profoundly deformed Piedmont rocks in the James River syn- cataclastically and have a pronounced cata- clinorium, on the eastern limb of the Catoctin clastic a lineation. Unlike the rocks in the Mountain-Blue Ridge anticlinorium have an Window area, those in the Piedmont part of s-surface pattern somewhat similar to that of the anticlinorium do not have a pronounced the basement gneisses, but with a better de- cataclastic fabric. -

Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey

Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey Lincoln "Colored" School, 1938. From the Library of Virginia: School Building Services Photograph Collection. Prepared by: History Matters, LLC Washington, DC September 2004 Sponsored by the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors & The Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library Leesburg, VA Loudoun County African-American Historic Architectural Resources Survey Prepared by: Kathryn Gettings Smith Edna Johnston Megan Glynn History Matters, LLC Washington, DC September 2004 Sponsored by the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors & The Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library Leesburg, VA Loudoun County Department of Planning 1 Harrison Street, S.E., 3rd Floor Leesburg, VA 20175 703-777-0246 Table of Contents I. Abstract 4 II. Acknowledgements 5 III. List of Figures 6 IV. Project Description and Research Design 8 V. Historic Context A. Historic Overview 10 B. Discussion of Surveyed Resources 19 VI. Survey Findings 56 VII. Recommendations 58 VIII. Bibliography 62 IX. Appendices A. Indices of Surveyed Resources 72 B. Brief Histories of Surveyed Towns, Villages, Hamlets, 108 & Neighborhoods C. African-American Cemeteries in Loudoun County 126 D. Explanations of Historic Themes 127 E. Possible Sites For Future Survey 130 F. Previously Documented Resources with Significance to 136 Loudoun County’s African-American History 1 Figure 1: Map of Loudoun County, Virginia with principal roads, towns, and waterways. Map courtesy of the Loudoun County Office of Mapping. 2 Figure 2. Historically African-American Communities of Loudoun County, Virginia. Prepared by Loudoun County Office of Mapping, May 15, 2001 (Map #2001-015) from data collected by the Black History Committee of the Friends of Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Va. -

Porcellian Club Centennial, 1791-1891

nia LIBRARY UNIVERSITY W CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO NEW CLUB HOUSE PORCELLIAN CLUB CENTENNIAL 17911891 CAMBRIDGE printed at ttjr itttirnsiac press 1891 PREFATORY THE new building which, at the meeting held in Febru- ary, 1890, it was decided to erect has been completed, and is now occupied by the Club. During the period of con- struction, temporary quarters were secured at 414 Harvard Street. The new building stands upon the site of the old building which the Club had occupied since the year 1833. In order to celebrate in an appropriate manner the comple- tion of the work and the Centennial Anniversary of the Founding of the Porcellian Club, a committee, consisting of the Building Committee and the officers of the Club, was chosen. February 21, 1891, was selected as the date, and it was decided to have the Annual Meeting and certain Literary Exercises commemorative of the occasion precede the Dinner. The Committee has prepared this volume con- taining the Literary Exercises, a brief account of the Din- ner, and a catalogue of the members of the Club to date. A full account of the Annual Meeting and the Dinner may be found in the Club records. The thanks of the Committee and of the Club are due to Brothers Honorary Sargent, Isham, and Chapman for their contribution towards the success of the Exercises Literary ; also to Brother Honorary Hazeltine for his interest in pre- PREFATORY paring the plates for the memorial programme; also to Brother Honorary Painter for revising the Club Catalogue. GEO. B. SHATTUCK, '63, F. R. APPLETON, '75, R. -

Let's Take a Hike in Catoctin Mountain Park Meghan Lindsey University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Tampa Library Faculty and Staff ubP lications Tampa Library 2008 Let's Take a Hike in Catoctin Mountain Park Meghan Lindsey University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tlib_facpub Part of the Education Commons Scholar Commons Citation Lindsey, Meghan, "Let's Take a Hike in Catoctin Mountain Park" (2008). Tampa Library Faculty and Staff Publications. 1. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tlib_facpub/1 This Data is brought to you for free and open access by the Tampa Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tampa Library Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SSACgnp.RA776.ML1.1 Let’s Take a Hike in Catoctin Mountain Park How many Calories will you burn off hiking a five-mile loop trail? Core Quantitative Literacy Topics Slope; contour maps Core Geoscience Subject Topographic maps Supporting Quantitative Literacy Topics Unit Conversions Arctangent, radians Reading Graphs Image from: http://www.nps.gov/cato Ratios and Proportions Percent increase Meghan Lindsey Department of Geology, University of South Florida, Tampa 33620 © 2008 University of South Florida Libraries. All rights reserved. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number NSF DUE-0836566. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. 1 Getting started After completing this module you should be able to: • use Excel spreadsheet to make your calculations. -

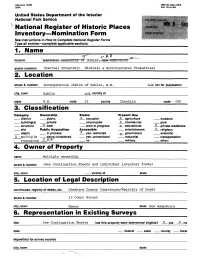

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Geologic Map of the Loudoun County, Virginia, Part of the Harpers Ferry Quadrangle

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-2173 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LOUDOUN COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PART OF THE HARPERS FERRY QUADRANGLE By C. Scott Southworth INTRODUCTION Antietam Quartzite constituted the Chilhowee Group of Early Cambrian age. Bedrock and surficial deposits were mapped in 1989-90 as part For this report, the Loudoun Formation is not recognized. As of a cooperative agreement with the Loudoun County Department used by Nickelsen (1956), the Loudoun consisted primarily of of Environmental Resources. This map is one of a series of geologic phyllite and a local uppermost coarse pebble conglomerate. Phyl- field investigations (Southworth, 1990; Jacobson and others, lite, of probable tuffaceous origin, is largely indistinguishable in the 1990) in Loudoun County, Va. This report, which includes Swift Run, Catoctin, and Loudoun Formations. Phyl'ite, previously geochemical and structural data, provides a framework for future mapped as Loudoun Formation, cannot be reliably separated from derivative studies such as soil and ground-water analyses, which phyllite in the Catoctin; thus it is here mapped as Catoctin are important because of the increasing demand for water and Formation. The coarse pebble conglomerate previously included in because of potential contamination problems resulting from the the Loudoun is here mapped as a basal unit of the overlying lower recent change in land use from rural-agricultural to high-density member of the Weverton Formation. The contact of the conglom suburban development. erate and the phyllite is sharp and is interpreted to represent a Mapping was done on 5-ft-contour interval topographic maps major change in depositional environment. -

Shannondale Springs

Shannondale Springs By William D. Theriault Like its competitors, Shannondale owed its patronage as much to its image and atmosphere as to the efficacy of its The Shannondale Springs resort, waters. Its fate depended as much on the located in Jefferson County, was one of owners' economic and political savvy as many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century on the staff's ability to stamp out a stray enterprises developed ostensibly to profit spark or sidestep the inevitable floods. from the curative powers of mineral This study explores the ownership, springs.1 The springs construction, and region ran the entire renovation of length of the Shannondale Springs Appalachian Chain and the factors from New York to contributing to its Alabama, with most growth, decline, and of the resorts being demise. located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of The site now known Virginia and along as Shannondale the Alleghenies in Springs was part of a West Virginia. much larger twenty- Springs varied in both nine thousand-acre temperature and tract called mineral content and "Shannandale" specific types were acquired in January thought to combat 1740 by William specific ills. Fairfax, nephew and Mineral springs agent of Thomas, began to gain Poster dated 1856 Lord Fairfax. In popularity in Virginia contemporary terms, during the mid-eighteenth century and Shannondale stretched along the continued to grow and prosper until the Shenandoah River from Castleman's Civil War. They began to prosper once Ferry in Clarke County, Virginia, to more at the end of the nineteenth century Harpers Ferry in present-day Jefferson and then declined again after World War County, West Virginia.