The Outcome of the Minority and Language Policy in Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate in Sweden During the Past Millennium - Evidence from Proxy Data, Instrumental Data and Model Simulations

Technical Report TR-06-35 Climate in Sweden during the past millennium - Evidence from proxy data, instrumental data and model simulations Anders Moberg, Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University Isabelle Gouirand, Kristian Schoning, Barbara Wohlfarth Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Erik Kjellstrom, Markku Rummukainen, Rossby Centre, SMHI Rixt de Jong, Department of Quaternary Geology, Lund University Hans Linderholm, Department of Earth Sciences, Goteborg University Eduardo Zorita, GKSS Research Centre, Geesthacht, Germany Svensk Karnbranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co December 2006 Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 Climate in Sweden during the past millennium - Evidence from proxy data, instrumental data and model simulations Anders Moberg, Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University Isabelle Gouirand, Kristian Schoning, Barbara Wohlfarth Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Erik Kjellstrom, Markku Rummukainen, Rossby Centre, SMHI Rixt de Jong, Department of Quaternary Geology, Lund University Hans Linderholm, Department of Earth Sciences, Goteborg University Eduardo Zorita, GKSS Research Centre, Geesthacht, Germany December 2006 This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. A pdf version of this document can be downloaded from www.skb.se Summary Knowledge about climatic variations is essential for SKB in its safety assessments of a geologi cal repository for spent nuclear waste. -

Geology of the Northern Norrbotten Ore Province, Northern Sweden Paper 11 (13) Editor: Stefan Bergman

Rapporter och meddelanden 141 Geology of the Northern Norrbotten ore province, northern Sweden Paper 11 (13) Editor: Stefan Bergman Rapporter och meddelanden 141 Geology of the Northern Norrbotten ore province, northern Sweden Editor: Stefan Bergman Sveriges geologiska undersökning 2018 ISSN 0349-2176 ISBN 978-91-7403-393-9 Cover photos: Upper left: View of Torneälven, looking north from Sakkara vaara, northeast of Kiruna. Photographer: Stefan Bergman. Upper right: View (looking north-northwest) of the open pit at the Aitik Cu-Au-Ag mine, close to Gällivare. The Nautanen area is seen in the back- ground. Photographer: Edward Lynch. Lower left: Iron oxide-apatite mineralisation occurring close to the Malmberget Fe-mine. Photographer: Edward Lynch. Lower right: View towards the town of Kiruna and Mt. Luossavaara, standing on the footwall of the Kiruna apatite iron ore on Mt. Kiirunavaara, looking north. Photographer: Stefan Bergman. Head of department, Mineral Resources: Kaj Lax Editor: Stefan Bergman Layout: Tone Gellerstedt och Johan Sporrong, SGU Print: Elanders Sverige AB Geological Survey of Sweden Box 670, 751 28 Uppsala phone: 018-17 90 00 fax: 018-17 92 10 e-mail: [email protected] www.sgu.se Table of Contents Introduktion (in Swedish) .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Lappstaden in Arvidsjaur Church Town Is Unique Portion of the Forested Areas in the Interior of – Nowhere Else Are There So Many Well-Preserved Upper Norrland

FOREST SAAMI UNIQUE The forest Saami in the past inhabited a large Lappstaden in Arvidsjaur church town is unique portion of the forested areas in the interior of – nowhere else are there so many well-preserved · 2013 TC G Upper Norrland. Today their territory is limited forest Saami gåhties (Saami pyramid-shaped G: INTIN R to the inland area between Vittangi in Norr- dwelling) as here. Their form combines that of the P YRÅ. YRÅ. botten County down to Malå in Västerbotten round gåhtie tent with the square timber dwelling. B PRÅK S X County with Arvidsjaur as the core area. The Lappstaden has never been used for permanent LE : E : N life of the forest Saami is adapted to that of living; only for overnight stays during church festi- O the forest reindeer, which finds all its forage vals. anslati . TR . N in forest areas and never needs to move to O mati the mountains. Before the 18th century, forest A POSITIVE ATMOSPHERE OR INF reindeer husbandry was small-scale, every The buildings in Lappstaden are owned by the R ultu household keeping about 10 domesticated re- forest Saami themselves and are still in use. Here, K MUNIN indeer. Hunting, and above all fishing, brought & people stay to spend time IN G HU the staple nutrition. together and the tradition :: N G DESI survives of spending the HIC P THE GREAT CHANGE night in Lappstaden A th th KIRUNA During the 18 and 19 centuries, conditions during the church & GR AND T X changed. The forestlands were populated by E feast, the last week- T non-nomadic settlers, who were allotted land end in August. -

TEACHING and CHURCH TRADITION in the KEMI and TORNE LAPLANDS, NORTHERN SCANDINAVIA, in the 1700S

SCRIPTUM NR 42 Reports from The Research Archives at Umeå University Ed. Egil Johansson ISSN 0284-3161 ISRN UM-FARK-SC--41-SE TEACHING AND CHURCH TRADITION IN THE KEMI AND TORNE LAPLANDS, NORTHERN SCANDINAVIA, IN THE 1700s SÖLVE ANDERZÉN ( Version in PDF-format without pictures, October 1997 ) The Research Archives Umeå University OCTOBER 1997 1 S 901 74 UMEÅ Tel. + 46 90-7866571 Fax. 46 90-7866643 2 THE EDITOR´S FOREWORD It is the aim of The Research Archives in Umeå to work in close cooperation with research conducted at the university. To facilitate such cooperation, our series URKUNDEN publishes original documents from our archives, which are of current interest in ongoing research or graduate courses at the university. In a similar way, research reports and studies based on historic source material are published in our publication series SCRIPTUM. The main purposes of the SCRIPTUM series are the following: 1. to publish scholarly commentaries to source material presented in URKUNDEN, the series of original documents published by The Research Archives; 2. to publish other research reports connected with the work of The Research Archives, which are considered irnportant for tbe development of research methods and current debate; 3. to publish studies of general interest to the work of The Research Archives, or of general public interest, such as local history. We cordially invite all those interested to read our reports and to contribute to our publication series SCRIPTUM, in order to further the exchange of views and opinions within and between different disciplines at our university and other seats of learning. -

Space-Related Education on the Kiruna Space Campus, Sweden

Space-related Education on the Kiruna Space Campus, Sweden The town of Kiruna lies approximately 140 kilometres above the Arctic Circle Space research and industry in northern Sweden. The high latitude Carol Norberg, The largest research organization in Kiruna Reader in Space Physics, makes Kiruna an attractive base for is the Swedish Institute of Space Physics, which Department of Space Sci- international space-related projects of carries out research in experimental space and ence, atmospheric physics. Measurements are made from many kinds. A space research insti- Umeå University, the ground, with balloons, and from satellites. Prob- Box 812, S-981 28 Kiruna, tute was first created in Kiruna in the ably the most well-known space centre in Kiruna is Sweden. 1950’s. During the last decade, there Esrange, a space facility belonging to the Swedish Space Corporation. Esrange has its own satellite has been a rapid expansion in the area station, and facilities for launching sounding rockets of space-related education at university and stratospheric balloons. Close to Esrange is the Swedish Institute of Space level, which has its foundations on the European Space Agency satellite station at Salmi- järvi. The headquarters of the European Incoherent Physics, Headquarter in local expertise in space science and Scatter Scientific Association (EISCAT) are located Kiruna. engineering. Through cooperation with Picture: IRF the Swedish Space Corporation stu- dents in Kiruna are offered the opportu- nity to participate in rocket and balloon launches as part of their education. The two most northern universities in Swe- den, Luleå University of Technology and Umeå University have formed a joint Department of Space Science located on the Kiruna Space Campus togeth- er with the Swedish Institute of Space Physics. -

International Rate Centers for Virtual Numbers

8x8 International Virtual Numbers Country City Country Code City Code Country City Country Code City Code Argentina Bahia Blanca 54 291 Australia Brisbane North East 61 736 Argentina Buenos Aires 54 11 Australia Brisbane North/North West 61 735 Argentina Cordoba 54 351 Australia Brisbane South East 61 730 Argentina Glew 54 2224 Australia Brisbane West/South West 61 737 Argentina Jose C Paz 54 2320 Australia Canberra 61 261 Argentina La Plata 54 221 Australia Clayton 61 385 Argentina Mar Del Plata 54 223 Australia Cleveland 61 730 Argentina Mendoza 54 261 Australia Craigieburn 61 383 Argentina Moreno 54 237 Australia Croydon 61 382 Argentina Neuquen 54 299 Australia Dandenong 61 387 Argentina Parana 54 343 Australia Dural 61 284 Argentina Pilar 54 2322 Australia Eltham 61 384 Argentina Rosario 54 341 Australia Engadine 61 285 Argentina San Juan 54 264 Australia Fremantle 61 862 Argentina San Luis 54 2652 Australia Herne Hill 61 861 Argentina Santa Fe 54 342 Australia Ipswich 61 730 Argentina Tucuman 54 381 Australia Kalamunda 61 861 Australia Adelaide City Center 61 871 Australia Kalkallo 61 381 Australia Adelaide East 61 871 Australia Liverpool 61 281 Australia Adelaide North East 61 871 Australia Mclaren Vale 61 872 Australia Adelaide North West 61 871 Australia Melbourne City And South 61 386 Australia Adelaide South 61 871 Australia Melbourne East 61 388 Australia Adelaide West 61 871 Australia Melbourne North East 61 384 Australia Armadale 61 861 Australia Melbourne South East 61 385 Australia Avalon Beach 61 284 Australia Melbourne -

New Research Supports Volcanic Origin of Kiruna-Type Iron Ores 12 April 2019

New research supports volcanic origin of Kiruna-type iron ores 12 April 2019 The origin and actual process of formation of Kiruna- type ores has remained highly controversial for over 100 years, with suggestions including a purely low-temperature hydrothermal origin, sea floor precipitation, a high-temperature volcanic origin from magma, and high-temperature magmatic fluids. To clarify the origins of Kiruna-type ores, a team of scientists from Uppsala University, the Geological Survey of Sweden, the Geological Survey of Iran, the Indian Institute of Technology in Bombay, and the Universities of Cardiff and Cape Town, led by Uppsala researcher Prof. Valentin Troll, employed Fe and O isotopes, the main elements in magnetite (Fe3O4), from Sweden, Chile and Iran to chemically fingerprint the processes that Credit: CC0 Public Domain led to formation of these ores. By comparing their data from Kiruna-type iron ores with an extensive set of magnetite samples from The origin of so-called Kiruna-type apatite-iron volcanic rocks as well as from known low- oxide ores has been the topic of a longstanding temperature hydrothermal iron ore deposits, the debate for over 100 years. In a new article researchers were able to show that more than 80 published in Nature Communications, a team of percent of their magnetite samples from Kiruna- scientists presents new and unambiguous data in type apatite-iron oxide ores were formed by high- favour of a magmatic origin for these important iron temperature magmatic processes in what must ores. The study was led by researchers from represent volcanic to shallow sub-volcanic settings. -

Mr. Ari Makela Torne Basin

Torne basin Workshop on transboundary water mgmt. in Western and Central Europe, Budapest, Hungary, 8-10.2011 Senior researcher Ari Mäkelä, Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) Torne basin General description of the Torne basin • The river length 470 km • Outlet at the Gulf of Bothnia, in the Baltic Sea • Two dams on the Torne’s tributaries --- the main channel free of dams • Altitude 200-500 m.a.s.l • Total 40’157 km 2 (Norway <1%, Finland 36%, Sweden 64%) • Waterbodies 5,5%, forests 92,2%, cropland 1,4%, urban/industrial 0,8% • 2,25 persons/ km 2 • 9 Natura areas, 3 RAMSAR sites Hydrology • Surface waters 13,6 km 3 /year • Ground waters 0,1 km 3 /year • Water per capita 350 863 m 3/year Discahrge characteristics 1991-2005 (1961-1990) 3 •Qav 430 (387) m /s 3 •Qmax 3179 (3667) m /s 3 •Qmin 58 (57) m /s • Peak flow in May 1093 (1037) m 3/s –June 1187 (1019) m 3/s Projected climate change impacts • Increase of 1,5-4,0 Celsius in annual mean temperature • 4-12 % increase in annual precipitation in forthcoming 50 years • Changes in seasonal hydrological change -5…+10%. The frequency of spring floods may increase • The lowest groundwater levels on late summer and in autumn may be even lower in the future than nowadays • Extreme water conditions overflows of treatment plants • In small groundwater bodies oxygen depletion, contents of dissolved iron and manganese and other metals may increase • Flood risk mgmt plan 2015-2021 Trans-boundary groundwaters • Not an issue, so far. -

FOOTPRINTS in the SNOW the Long History of Arctic Finland

Maria Lähteenmäki FOOTPRINTS IN THE SNOW The Long History of Arctic Finland Prime Minister’s Office Publications 12 / 2017 Prime Minister’s Office Publications 12/2017 Maria Lähteenmäki Footprints in the Snow The Long History of Arctic Finland Info boxes: Sirpa Aalto, Alfred Colpaert, Annette Forsén, Henna Haapala, Hannu Halinen, Kristiina Kalleinen, Irmeli Mustalahti, Päivi Maria Pihlaja, Jukka Tuhkuri, Pasi Tuunainen English translation by Malcolm Hicks Prime Minister’s Office, Helsinki 2017 Prime Minister’s Office ISBN print: 978-952-287-428-3 Cover: Photograph on the visiting card of the explorer Professor Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Taken by Carl Lundelius in Stockholm in the 1890s. Courtesy of the National Board of Antiquities. Layout: Publications, Government Administration Department Finland 100’ centenary project (vnk.fi/suomi100) @ Writers and Prime Minister’s Office Helsinki 2017 Description sheet Published by Prime Minister’s Office June 9 2017 Authors Maria Lähteenmäki Title of Footprints in the Snow. The Long History of Arctic Finland publication Series and Prime Minister’s Office Publications publication number 12/2017 ISBN (printed) 978-952-287-428-3 ISSN (printed) 0782-6028 ISBN PDF 978-952-287-429-0 ISSN (PDF) 1799-7828 Website address URN:ISBN:978-952-287-429-0 (URN) Pages 218 Language English Keywords Arctic policy, Northernness, Finland, history Abstract Finland’s geographical location and its history in the north of Europe, mainly between the latitudes 60 and 70 degrees north, give the clearest description of its Arctic status and nature. Viewed from the perspective of several hundred years of history, the Arctic character and Northernness have never been recorded in the development plans or government programmes for the area that later became known as Finland in as much detail as they were in Finland’s Arctic Strategy published in 2010. -

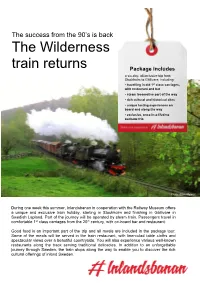

The Wilderness Train Returns

The success from the 90’s is back The Wilderness train returns Package includes a six-day, all-inclusive trip from Stockholm to Gällivare, including: • travelling in old 1st class carriages, with restaurant and bar • steam locomotive part of the way • rich cultural and historical sites • unique tasting experiences on board and along the way • exclusive, once-in-a-lifetime package trip Photo: Björn Malmer During one week this summer, Inlandsbanan in cooperation with the Railway Museum offers a unique and exclusive train holiday, starting in Stockholm and finishing in Gällivare in Swedish Lapland. Part of the journey will be operated by steam train. Passengers travel in comfortable 1st class carriages from the 20th century, with on-board bar and restaurant. Good food is an important part of the trip and all meals are included in the package tour. Some of the meals will be served in the train restaurant, with linen-clad table cloths and spectacular views over a beautiful countryside. You will also experience various well-known restaurants along the track serving traditional delicacies. In addition to an unforgettable journey through Sweden, the train stops along the way to enable you to discover the rich cultural offerings of inland Sweden. ITINERARY DAY BY DAY Mon 2 July | Stockholm - Mora The Wilderness Train departs from Stockholm Central station in the morning for the first stretch taking us to Mora in the county of Dalecarlia. Besides enjoying the train ride, you will be served a delicious lunch in the restaurant carriage before visiting Verket/Avesta Art, where industrial history and contemporary art are in focus. -

LKAB Is Looking for Talented Engineers in Mining

LKAB is looking for talented Engineers in Mining LKAB is currently engaged in an important process to increase production, develop and streamline the existing production systems in our mines, and design new smart and fossil-free mining systems below our current main levels in our underground mines in Kiruna and Malmberget. These great challenges and opportunities will require additional talented mining engineers. Therefore, we are looking for mining engineers that are interested in being part of our journey towards the future, and are interested in technical development, innovation, and research in mining, with a focus on mine design, mining methods, rock mechanics, autonomous mining and underground logistics. Your qualifications All positions require a strong interest in identifying and overcoming the challenges that will be faced when mining below the present mining system. Qualities fundamental to these jobs are a passion for technology and problem-solving, a strong interest in suggesting and testing new solutions, and good analytical abilities. You enjoy teamwork and have good communication skills, and are interested in creating an international network of contacts. You hold a MSc or a PhD in one of the following areas: • mine design • mining methods • rock mechanics • geotechnical numerical analysis • mine seismology • autonomous mining • mining systems or • underground logistics Industrial experience is of great importance but all candidates will be considered. Those with similar backgrounds are also welcome to apply for one of the positions. You will be based in the city of Kiruna or Gällivare, close to the mining operations. Kiruna and Gällivare are situated in Swedish Lapland, above the Arctic Circle. -

Torniohaparanda (Finland Sweden) EMBRACE the BORDER

Europan 14 – TornioHaparanda (Finland Sweden) EMBRACE THE BORDER Tornio Finland N Haparanda Sweden SCALE: L – urban and architectural HOW CAN THE SITE CONTRIBUTE to THE PRODUCTIVE CITY StrateGY LOCATION: TornioHaparanda CITY? TornioHaparanda is located at the north end of the Bothnian Bay in Lap- SITE FAMILY: From Functionalist Infrastructures to Productive City Tornio in Finland and Haparanda in Sweden are developing their city land. Tornio in Finland and Haparanda in Sweden make up an internatio- POPUlation: 32 500 centers to become one commercial and functional entity. The project site nal twin city that has 32 500 inhabitants. The TornioHaparanda area is a STUDY SITE: 60 ha PROJECT SITE: 24 ha at the south end of Suensaari island and the north end of Haparanda centre of cross-border trade and known for its steel industry. The deve- SITE PROPOSED BY: TornioHaparanda twin city downtown is important and visible in the urban structure. It holds poten- lopment for building one joint center for the two cities started already 20 ACTORS INVOLVED: City of Tornio, City of Haparanda tial to unite the two cities, yet it is mainly unbuilt and underutilised at the year ago and the process continues with Europan 14. OWNERS OF THE SITE: City of Tornio, ELY center of Lapland, moment. The busy highway E4 runs through the area separating parts of Orthodox parish of Lapland, City of Haparanda, IKEA the site from Tornio and Haparanda city centers. POST COMPETITION PHASE: Post-competition seminar, selection The objective is to find both functional and urban ideas to connect the of one winning team for an implementation process project site to the city centers and their urban structures.