A Socialist, Feminist, and Anti-Racist Journal on the Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

America's Empire of Bases

Volume 1 | Issue 5 | Article ID 2029 | May 23, 2003 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus America's Empire of Bases Chalmers Johnson America's Empire of Bases weapons for the armed forces or, like the now well-publicized Kellogg, Brown & Root by Chalmers Johnson company, a subsidiary of the Halliburton Corporation of Houston, undertake contract As distinct from other peoples, most Americans services to build and maintain our far-flung do not recognize -- or do not want to recognize outposts. One task of such contractors is to -- that the United States dominates the world keep uniformed members of the imperium through its military power. Due to government housed in comfortable quarters, well fed, secrecy, our citizens are often ignorant of the amused, and supplied with enjoyable, fact that our garrisons encircle the planet. This affordable vacation facilities. Whole sectors of vast network of American bases on every the American economy have come to rely on continent except Antarctica actually constitutes the military for sales. On the eve of our second a new form of empire -- an empire of bases with war on Iraq, for example, while the Defense its own geography not likely to be taught in any Department was ordering up an extra ration of high school geography class. Without grasping cruise missiles and depleted-uranium armor- the dimensions of this globe-girdlingpiercing tank shells, it also acquired 273,000 Baseworld, one can't begin to understand the bottles of Native Tan sunblock, almost triple its size and nature of our imperial aspirations or 1999 order and undoubtedly a boon to the the degree to which a new kind of militarism is supplier, Control Supply Company of Tulsa, undermining our constitutional order. -

Nonviolent Alternatives for Social Change

CONTENTS NONVIOLENT ALTERNATIVES FOR SOCIAL CHANGE Nonviolent Alternatives for Social Change - Volume 1 No. of Pages: 450 ISBN: 978-1-84826-220-1 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-670-4 (Print Volume) For more information of e-book and Print Volume(s) order, please click here Or contact : [email protected] ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) NONVIOLENT ALTERNATIVES FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CONTENTS Understanding Nonviolence in Theory and Practice 1 Ralph Summy, The Australian Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia 1. Introduction 2. Difference between Peace and Nonviolence 3. Different Roads to Peace 4. Obstacles to Nonviolent Option 5. Typology of Nonviolence (4 ‘P’s) 6. Quadrant A – Principled/Personal 6.1. Christianity 6.1.1. Anabaptists 6.1.2. Other sects 6.1.3. Leo Tolstoy 6.2. Judaism 6.3. Buddhism 6.4. Jainism 6.5. Islam 6.6. Stoicism 6.7. Humanism 7. Quadrant B – Pragmatic/Personal 8. Quadrant C – Principled/Public 8.1. Gandhi 8.2. Martin Luther King 8.3. Archbishop Desmond Tutu 8.4. Dalai Lama XIV 8.5. Aung San Suu Kyi 8.6. Daisaku Ikeda 8.7. Native Hawai’ian Society 8.8. Society of Friends 9. Quadrant D – Pragmatic/Public 9.1. Dependency Theory of Power 9.1.1. Ruler’s Sources of Power 9.1.2. Why People Obey 9.1.3. Matrix of Dependency 9.2. Independence (10 ’S’s) 9.3. Blueprint of a Critique 10. Conclusion Countering with Nonviolence the Pervasive Structural Violence of Everyday Life- The Case of a Small Italian Townships 40 Piero P. -

European Journal of American Studies, 2-2 | 2007 Taking up the White Man’S Burden? American Empire and the Question of History 2

European journal of American studies 2-2 | 2007 Autumn 2007 Taking up the White Man’s Burden? American Empire and the Question of History Johan Höglund Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/1542 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.1542 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Johan Höglund, “Taking up the White Man’s Burden? American Empire and the Question of History”, European journal of American studies [Online], 2-2 | 2007, document 5, Online since 14 December 2007, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/1542 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/ejas.1542 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Taking up the White Man’s Burden? American Empire and the Question of History 1 Taking up the White Man’s Burden? American Empire and the Question of History Johan Höglund 1. Introduction 1 If Britain obtained its empire in ''a fit of absence of mind,'' as Sir John Seeley once remarked,1 the United States has acquired its empire in a state of deep denial, or so Michael Ignatieff argued in an article from 2003.2 It would seem that this denial characterizes large portions of the American public and most members of the current Presidential administration. However, an increasing number of political and historical writers and journalists have begun to discuss the notion that the United States may, after all, resemble a traditional empire.3 2 The two Bush administrations have been forced to react to this notion on a number of occasions. -

10 ICPNA Brochure

th ANUVIBHA 10INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON PEACE AND NONVIOLENT ACTION 17 Dec - 20 Dec, 2019 Theme Educating and Training Children and Youths in Nonviolence An Imperative for the Creation of Nonkilling Societies and a Sustainable Future organized by ANUVRAT GLOBAL ORGANIZATION (ANUVIBHA) associated with UN-DGC in academic collaboration with THE CENTRE FOR GLOBAL NONKILLING Honolulu, USA in Special Consultative Status ECOSOC with UN and INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PEACE STUDIES AND GLOBAL PHILOSOPHY (IIPSGP), UK, FRANCE ANUVRAT GLOBAL ORGANIZATION (ANUVIBHA) v.kqozr fo'o Hkkjrh ¼v.kqfoHkk½ Opp. Gaurav Tower, JLN Marg, JAIPUR - 302 017 INDIA Our Spiritual Patron Anuvrat Anushasta His Holiness Acharya Mahashraman His Holiness Acharya Mahashraman is successor to his many-splendoured guru HH Acharya Mahapragya. He is the eleventh Acharya of the Jain Swetamber Terapanth sect and the Spiritual Head of Anuvrat Movement which aims at the rejuvenation of moral and spiritual values among people of the world. He is also a Jain monk who strictly observes the vow of ahimsa (nonviolence) in its entirety in thought, word and deed in addition to the other four great vows of truth, non-stealing, non-possession and celibacy. He is young, dynamic, sagacious and is an embodiment of spirituality. Currently, he is leading Ahimsa Yatra (a journey on foot) across the country to create nonviolence awareness among the masses. th 10INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON PEACE AND NONVIOLENT ACTION (10th ICPNA) Aims and Objectives of the 10th ICPNA The 10th ICPNA aims to discuss and propose a viable system for training the children, youths and adults across the world in nonviolence. -

Models of the Developmental State

Models of the developmental state Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira Abstract This paper seeks to understand the developmental state and its historical role in industrial revolutions and afterwards. First, the developmental state is defined as an alternative to the liberal state. Second, it is argued that industrial revolutions have always taken place within the framework of a developmental state. Third, four models of developmental states are defined according to the point in time at which the industrial revolution took place and the central or peripheral character of the country. Fourth, the paper describes how the state withdraws partially from the economy after the industrial revolution, but the developmental state continues to have a major role in directing industrial policy and in conducting an active macroeconomic policy. Keywords Public administration, economic planning, macroeconomics, liberalism, nationalism, economic policy, economic development JEL classification O10, O11, O19 Author Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira is an Emeritus Professor with the Department of Economics of the Sao Paulo School of Economics, Getulio Vargas Foundation, Brazil. Email: [email protected]. 36 CEPAL Review N° 128 • August 2019 I. Introduction In the 1950s, Brazilian political scientists and economists identified “developmentalism” as a set of political ideas and economic strategies that drove Brazil’s rapid industrialization and underpinned the coalition of social classes identified with national development. Hélio Jaguaribe (1962, p. 208) stated in the early 1960s that “the core thesis of developmentalism is that the promotion of economic development and the consolidation of nationality stand as two correlated aspects of a single emancipatory process”. Through “national developmentalism”, which would become the established term for the country’s development strategy, Brazilian society was successfully overcoming the patrimonial state that characterized its politics until 1930. -

Models of Developmental State

1 Working 426 Setembro de 2016 Paper Models of developmental state Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira Os artigos dos Textos para Discussão da Escola de Economia de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas são de inteira responsabilidade dos autores e não refletem necessariamente a opinião da FGV-EESP. É permitida a reprodução total ou parcial dos artigos, desde que creditada a fonte. Escola de Economia de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas FGV-EESP www.eesp.fgv.br TEXTO PARA DISCUSSÃO 426 • SETEMBRO DE 2016 • 1 Models of developmental state Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira July 2016. Abstract. This paper searches to understand the developmental state and its historical role in the industrial revolution and after it. First, the developmental state is defined as an alternative to the liberal state. Second, it was in the framework of a developmental state that industrial revolutions took place, and four models of developmental state are defined. Third, after the industrial revolution, the state withdraws partially from the economy, but the developmental state continues to have a major role in assuring the general conditions that make competitive the competent business enterprises in each country – in conducing an active macroeconomic policy, particularly an exchange rate policy, in coordinating the non-competitive industries, and in conducing strategic industrial and technological policy. The paper concludes by comparing developmentalism with nationalism. Key words: Developmental state, developmentalism, economic liberalism, nationalism Resumo. Este artigo busca compreender o Estado desenvolvimentista e seu papel histórico na revolução industrial e depois dela. Em primeiro lugar, o Estado desenvolvimentista é definido como uma alternativa para o Estado liberal. -

Buddhism and Weapons of Mass Destruction: an Oxymoron?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Works 12 Buddhism and Weapons of Mass Destruction An Oxymoron? Donald K. Swearer taking stock of a dilemma One of the most enduring principles of Buddhist ethics is the teaching of nonviolence (ahimsa), and the first of the five basic moral precepts is not to take the life of a sentient being. In the light of these teachings, is a conver- sation about Buddhist perspectives on weapons with the capacity for large- scale death and destruction not a contradiction in terms? David Chappell describes the tensions in the tradition between the normative Buddhist prin- ciples of peace and nonviolence and the actual behaviors of Buddhists both past and present, for example, rulers who have promoted war in defense of nation and religion and clergy who supported militarist regimes. In the light of this tension, Gananath Obeyesekere holds that Buddhism’s noble principles are inevitably compromised by history and politics, a point of view that can be applied to other religious traditions, as well.1 To situate the Buddhist ethical principles of peace, nonviolence, and nonkilling beyond history, however, obviates any capacity they might have to challenge and, it is hoped, to transform violence in any form, including violence associated with weapons of mass destruction. Whether Buddhism and the other world religions have anything uniquely distinctive to contribute to the specific pol- icy decisions related to debates about WMD, such as utilization, deterrence, and proliferation, is moot. What the world’s religions, including Buddhism, do have to offer, however, is a vision of hope where the values of peace, non- violence, compassion, and the opportunity for human beings to flourish cooperatively are uppermost. -

Recent U.S. Foreign Policy

Recent U.S. Foreign Policy Two takes on “Empire” Bacevich – Take One American Empire from the End of the Cold War to 9/11 • “Globalization “Is” the international system that replaced the Cold War • The “desired” NSC-68 state of affairs – US economic (dollar), cultural, military and political “hegemony • The sense of “unlimited opportunities – a new global order • Claim – US policy derived from “American Exceptionalism • No to power politics ---to achieve values • No to War -- use force in measured amounts • No to limits -- Resources were no constraint The 1991 Gulf War • The War to establish a new world order – get rid of tyrants and demonstrate US military superiority --- dissuade challengers and get those not in line with the new world order in line • War a military success but little else • New problems brewing and old ones lingering • War lords (Somalia) • Terrorism (bin Laden) • Tyrants (Iraq, N. Korea, Serbia) • Revolutionary regimes (Iran) • Destabilized old empire (Russia) • Ethnic conflicts ((Rwanda, Congo, Bosnia) • As a result in the 90s the US ended up using military force more and less Gunboats and Gurkhas – the militarization of US Foreign Policy • Note our claim is that of course gunboats and gurkhas is nothing new and the militarization of US FP started long ago • Bacevich argues that in the 90s US force was heavily used (Yes) -- in Albrights language “the indispensible nation” -- but puts Somalia – low to no causalities and play to US military strengths • Gunboats – cruise missiles and precision munitions (Iraq, Bosnia, -

Islam and Nonviolence

Islam and Nonviolence ISLAM AND NONVIOLENCE Edited by Glenn D. Paige Chaiwat Satha-Anand (Qader Muheideen) Sarah Gilliatt Center for Global Nonviolence 2001 Copyright © 1993 by the Center for Global Nonviolence Planning Project, Spark M. Matsunaga Institute for Peace, University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822, U.S.A. Copyright © 1999 by the nonprofit Center for Global Nonviolence, Inc., 3653 Tantalus Drive, Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822-5033. Website: www.globalnonviolence.org. Email: [email protected]. Copying for personal and educational use is encouraged by the copyright holders. ISBN 1-880309-0608 BP190.5.V56I85 1992 To All Nonviolent Seekers of Truth CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction Chaiwat Satha-Anand (Qader Muheideen 1 The Nonviolent Crescent: Eight Theses on Muslim Nonviolent Actions Chaiwat Satha-Anand (Qader Muheideen) 7 Islam, Nonviolence, and Global Transformation Razi Ahmad 27 Islam, Nonviolence, and National Transformation Abdurrahman Wahid 53 Islam, Nonviolence, and Social Transformation Mamoon-al-Rasheed 59 Islam, Nonviolence, and Women Khalijah Mohd. Salleh 109 Islam, Nonviolence, and Interfaith Relations M. Mazzahim Mohideen 123 Glossary 145 Suggested Reading 151 Contributors 153 Index of Qur‘anic Verses 157 Index 159 PREFACE The Center for Global Nonviolence Planning Project is pleased to present this report of an international exploratory seminar on Islam and nonviolence held in Bali, Indonesia, during February 14-19, 1986. The origins of the seminar are explained in the Introduction by Chaiwat Satha-Anand (Qader Muheideen). We are grateful to the United Nations University, and especially to the then Vice-Rector Kinhide Mushakoji and senior programme officer Dr. Janusz Golebiowski, of its Regional and Global Studies Division, and to the cosponsor, Indonesia’s Nahdatul Ulama, led by Abdurrahman Wahid, for making the seminar possible. -

Buddhism and Nonviolent Global Problem-Solving

Buddhism and Nonviolent Global Problem-Solving Ulan Bator Explorations BUDDHISM AND NONVIOLENT GLOBAL PROBLEM-SOLVING Ulan Bator Explorations Edited by Glenn D. Paige and Sarah Gilliatt Center for Global Nonviolence 2001 Copyright ©1991 by the Center for Global Nonviolence Planning Project, Spark M. Matsunaga Institute for Peace, University of Hawai'i, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96822. Copyright ©1999 by the nonprofit Center for Global Nonviolence, Inc., 3653 Tantalus Drive, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96822-5033. Website: www.globalnonviolence.org. Email: [email protected]. Copying for personal and educational use is encouraged by the copyright holders. Original publication was made possible by the generosity of the Korean Buddhist Dae Won Sa Temple of Hawai'i. Now Mu-Ryang-Sa (Broken Ridge Buddhist Temple), 2408 Halelaau Place, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96816. By gentle and skillful means based on reason. --From the Mongolian Buddhist tradition CONTENTS Preface Introduction 1 OPENING ADDRESS From Violent Combat to Playful Exchange of Flowers Khambo Lama Kh. Gaadan 7 PERSPECTIVES: BUDDHISM, LEADERSHIP, SCHOLARSHIP, ACTION Global Problem-Solving: A Buddhist Perspective Sulak Sivaraksa 15 The United Nations, Religion, and Global Problems: Facing a Crisis of Civilization Kinhide Mushakoji 33 Visioning a Peaceful World Johan Galtung 37 Nonviolent Buddhist Problem-Solving in Sri Lanka A.T. Ariyaratne 65 GLOBAL PROBLEM-SOLVING Five Principles for a New Global Moral Order Thich Minh Chau 91 The Importance of the Buddhist concept of Karma for World Peace Yoichi Kawada 103 Disarmament Efforts from the Standpoint of Mahayana Buddhism Yoichi Shikano 115 Buddhism and Global Economic Justice Medagoda Sumanatissa 125 "buddhism" and Tolerance for Diversity of Religion and Belief Sulak Sivaraksa 137 Nonviolent Ecology: The Possibilities of Buddhism Leslie E. -

Complete Christmas Songbook

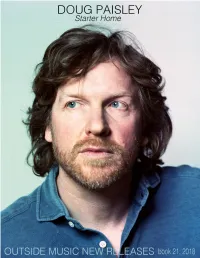

NEW RELEASES - ORDER FORM Outside Music, 7 Labatt Ave., Suite 210, Toronto, On, M5A 1Z1. FAX: 416-461-0973 / 1-800-392-6804. EMAIL: [email protected] CAT. NO. ARTIST TITLE LABEL GENRE UPC CONFPPD REL. DATE QTY 43563-1053-3 PAISLEY, DOUG Starter Home SD / No Quarter Rock-Pop 843563105337 CD$ 12.00 2-Nov-18 NOQ059 PAISLEY, DOUG Starter Home SD / No Quarter Rock-Pop 843563105313 LP$ 16.00 2-Nov-18 JAG330CS UNKNOWN MORTAL O IC-01 Hanoi SD / Jagjaguwar Experimen 656605233055 CS 8.00$ 26-Oct-18 56605-2330-2 UNKNOWN MORTAL O IC-01 Hanoi SD / Jagjaguwar Experimen 656605233024 CDEP$ 12.00 26-Oct-18 JAG330 UNKNOWN MORTAL O IC-01 Hanoi SD / Jagjaguwar Experimen 656605233017 12" EP $ 14.00 26-Oct-18 87828-0432-2 HOW TO DRESS WELLThe Anteroom Domino Rock-Pop 887828043224 CD$ 12.80 19-Oct-18 WIG432 HOW TO DRESS WELLThe Anteroom (180g LPx2) Domino Rock-Pop 887828043217 LPx2$ 25.60 19-Oct-18 87828-0817-2 HOLTER, JULIA Aviary Domino Rock-Pop 887828041725 CDx2$ 13.67 26-Oct-18 WIG417 HOLTER, JULIA Aviary Domino Rock-Pop 887828041718 LPx2$ 25.60 26-Oct-18 WIG417X HOLTER, JULIA Aviary (Indie Only - clear viny Domino Rock-Pop 887828041732 LPx2$ 25.60 26-Oct-18 66561-0138-2 MOSS, JESSICA Entanglement Constellation Rock-Pop 666561013820 CD$ 10.00 26-Oct-18 CST138 MOSS, JESSICA Entanglement Constellation Rock-Pop 666561013813 LP$ 14.25 26-Oct-18 28070-6355-2 SPECTRES Last Days Artoffact Records Punk 628070635528 CD$ 10.00 19-Oct-18 28070-6356-2 SPECTRES Nothing to Nowhere Artoffact Records Punk 628070635627 CD$ 10.00 19-Oct-18 28070-6357-2 SPECTRES Utopia