JOHN HOOK “Sandakan Death Marches – Trials and Tribulations”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

Necessary Chicanery : Operation Kingfisher's

NECESSARY CHICANERY: OPERATION KINGFISHER’S CANCELLATION AND INTER-ALLIED RIVALRY Gary Followill Z3364691 A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters by Research University of New South Wales UNSW Canberra 17 January 2020 1 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Australia's Global University Surname/Family Name Followill Given Name/s GaryDwain Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar MA Faculty AOFA School HASS Thesis Title Necessary Chicanery: Operation Kingfisher'scancellation and inter-allied rivalry Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines the cancellation of 'Operation Kingfisher' (the planned rescue of Allied prisoners of war from Sandakan, Borneo, in 1945) in the context of the relationship of the wartime leaders of the United States, Britain and Australia and their actions towards each other. It looks at the co-operation between Special Operations Australia, Special Operations Executive of Britain and the US Officeof Strategic Services and their actions with and against each other during the Pacific War. Based on hithertounused archival sources, it argues that the cancellation of 'Kingfisher' - and the failure to rescue the Sandakan prisoners - can be explained by the motivations, decisions and actions of particular British officers in the interplay of the wartime alliance. The politics of wartime alliances played out at both the level of grand strategy but also in interaction between officers within the planning headquarters in the Southwest Pacific Area, with severe implications for those most directly affected. Declaration relating to disposition of project thesis/dissertation I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here afterknow n, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. -

Supporting Us with the Trek! 75Th Anniversary

April 30 TPI Victoria Inc. (the Totally & Supporting us Permanently Incapacitated Ex- Day 7: Sandakan Death March Servicemen & Women’s Association of Victoria Inc) mission is to Distance 12kms with the trek! safeguard and support the interests Walking time 6 Hours and welfare of all Members, their Includes: Breakfast/Lunch/Dinner Russell Norman Morris Families & Dependants. is an Australian singer- songwriter and guitarist The way TPI are enabled to provide this support is to raise Transfer to Muruk village by bus before we commence who had five Australian funds through exciting events and adventures like the a steep ascent up Marakau Hill, also known as Botterill’s Top 10 singles during the Sandakan TPI Tribute Trek ANZAC Day 2020. Hill, named after Sandakan Death March survivor Keith late 1960s and early 1970s. Botterill. Botterill trekked up this hill 6 times lugging 24 April - 2 May (8 Nights, 9 Days) 20kg bags of rice to keep himself fit and also give him a Russell is also a big Wild Spirit Adventures provides a ANZAC DAY 2020 chance to pinch some rice to help his escape. supporter of TPI Victoria Inc. Dawn Service unique experience that takes you to Inc. and it is our pleasure the heart and soul of the places they We then follow a short steep trek through jungle, before to have him supporting visit – like nobody else can. descending and crossing Ranau Plain for lunch and pay us on the Sandakan TPI our respects at the Ranau POW Camp site. We then visit Tribute Trek ANZAC The adventures teach participants the magnificently restored Kundasang War Memorial to Day 2020. -

Kinta Valley, Perak, Malaysia

Geological Society of Malaysia c/o Department of Geology University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur +603-79577036 (voice) +603-79563900 (fax) [email protected] http://www.gsm.org.my/ PERSATUAN GEOLOGI MALAYSIA GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALAYSIA COUNCIL 2013-2014 PRESIDENT : PROF. DR. JOY JACQUELINE PEREIRA (UKM) VICE-PRESIDENT : DR. MAZLAN MADON (PETRONAS) IMM. PAST PRESIDENT : DATO’ YUNUS ABDUL RAZAK (JMG) SECRETARY : MR. LING NAN LEY (JMG) ASSISTANT SECRETARY : MR. LIM CHOUN SIAN (UKM) TREASURER : MR. AHMAD NIZAM HASAN (GEOSOLUTION RESOURCES) EDITOR : ASSOCIATE PROF. DR. NG THAM FATT (UM) COUNCILLORS : MR. TAN BOON KONG (CONSULTANT) DR. NUR ISKANDAR TAIB (UM) DR. TANOT UNJAH (UKM) DR. SAMSUDIN HJ TAIB (UM) DR. MEOR HAKIF AMIR HASSAN (UM) MR. ROBERT WONG (PETRONAS) MR. NICHOLAS JACOB (JKR) MR. ASKURY ABD KADIR (UTP)* NATIONAL GEOSCIENCE CONFERENCE 2013 ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN : DR. KAMALUDIN B. HASSAN (JMG PERAK) TECHNICAL CHAIRMAN : MR. HJ. ASKURY B. ABD. KADIR (UTP) TREASURER : MR. AHMAD NIZAM B. HASAN (GSM) SECRETARY/MEDIA : MS SUZANNAH BT AKMAL (JMG PERAK) ASST. SECRETARY : MR. MOHD. SHAHRIZAL B. MOHAMED SHARIFODIN (JMG PERAK) REGISTRATION : MR. LING NAN LEY (GSM) MS ANNA LEE (GSM) PRE-CONFERENCE FIELDTRIP AND : MR. HAJI ISMAIL B. IMAN (JMG PERAK) SPOUSE PROGRAM SPONSORSHIPS : MR AHMAD ZUKNI B. AHMAD KHALIL (JMG MALAYSIA) TEXT FOR SPEECHES : TUAN RUSLI B. TUAN MOHAMED (JMG PERAK) HOTEL AND ACCOMODATION : MR. MOHAMAD SARI B. HASAN (JMG PERAK) PROTOCOL AND SOUVENIRS : MS. MARLINDA BT DAUD (JMG MALAYSIA) COMMITTEE MEMBERS : MR. YUSNIN B. ZAINAL ABIDIN (IPOH CITY COUNCIL) MR SAW LID HAW (PERAK QUARRIES ASSOC.) PPeerrssaattuuaann GGeeoollooggii MMaallaayyssiiaa GGeeoollooggiiccaall SSoocciieettyy ooff MMaallaayyssiiaa PPrroocceeeeddiinnggss ooff tthhee NNAATTIIOONNAALL GGEEOOSSCCIIEENNCCEE CCOONNFFEERREENNCCEE 22001133 Kinta Riverfront Hotel and Suites, Ipoh 8-9th June 2013 Edited by: Nur Iskandar Taib Co-organizers: Copyright: Geological Society of Malaysia, 2013-05-29 All rights reserved. -

University of Perpetual Help System-DALTA College of Law

University of Perpetual Help System-DALTA College of Law FOREWORD Philippines maintains a dormant claim over the sovereignty of eastern Sabah based on the claim that in 1658 the Sultan of Brunei had ceded the northeast portion of Borneo to the Sultan of Sulu; and that later in 1878, an agreement was signed by the Sultan of Sulu granting the North Borneo Chartered Company a permanent lease over the territory. Malaysia considered this dispute as a "non-issue", as there is no desire from the actual people of Sabah to be part of the Philippines or of the Sultanate of Sulu. As reported by the Secretary- General of the United Nations, the independence of North Borneo was brought about as the result of the expressed wish of the majority of the people of the territory in a 1963 election. This research will determine whether or not Philippines have proprietary rights over Sabah. Jennylyn B. Albano UPHSD- College of Law 1 | P a g e INTRODUCTION This research will focus on the History of Sabah and determination of whether who really owns it. As we all know even before our ancestors are already fighting for our right over this state however, up until now dispute is still on going. Sabah is one of the 13 member states of Malaysia, and is its easternmost state. It is located on the northern portion of the island of Borneo. It is the second largest state in the country after Sarawak, which it borders on its southwest. It also shares a border with the province of East Kalimantan of Indonesia in the south. -

![Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY - Tuesday, 8 May 2007] P1737b-1737B Mr Alan Carpenter](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3583/extract-from-hansard-assembly-tuesday-8-may-2007-p1737b-1737b-mr-alan-carpenter-2573583.webp)

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY - Tuesday, 8 May 2007] P1737b-1737B Mr Alan Carpenter

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY - Tuesday, 8 May 2007] p1737b-1737b Mr Alan Carpenter ANZAC DAY - SANDAKAN Statement by Premier MR A.J. CARPENTER (Willagee - Premier) [2.01 pm]: From 22 to 25 April 2007 I visited Malaysia at the invitation of the State Secretary of Sabah. The main purpose of the travel was to commemorate Anzac Day in Sandakan, Sabah, to remember and honour more than 2 400 Australian and British soldiers, including 137 Western Australians, killed in the horrific Sandakan death marches in World War II. En route to Sandakan, we stopped at Kota Kinabalu, where I met with the Chief Minister of Sabah, YAB Datuk Musa Haji Aman. On arrival in Sandakan, I was welcomed by the President of Sandakan Municipal Council, Mr Yeo Boon Hai, who continued to host me throughout my visit. The Anzac Day dawn service was held at the Sandakan Memorial Park, and was the first service organised by the commonwealth government, although services have been held at the site for many years. More than 300 people from all over Australia and Malaysia attended the service. My parliamentary colleagues Mr Max Trenorden, MLA, and Mr Nigel Hallett, MLC, also attended and joined me on various tours and official functions throughout the visit. I am sure they would both agree with me that the Anzac Day dawn service was incredibly moving. The Sandakan death marches were a shocking and tragic time in the shared history of Australia and Malaysia. The commemoration is a time when people from both countries remember and acknowledge the horror of war. -

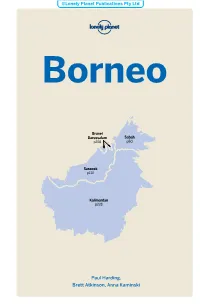

Borneo-5-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Borneo Brunei Darussalam Sabah p208 p50 Sarawak p130 Kalimantan p228 Paul Harding, Brett Atkinson, Anna Kaminski PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Borneo . 4 SABAH . 50 Sepilok . 90 Borneo Map . 6 Kota Kinabalu . 52 Sandakan Archipelago . 94 Deramakot Forest Borneo’s Top 17 . 8 Tunku Abdul Rahman National Park . 68 Reserve . 95 Need to Know . 16 Pulau Manukan . 68 Sungai Kinabatangan . 96 First Time Borneo . 18 Pulau Mamutik . 68 Lahad Datu . 101 Pulau Sapi . 69 Danum Valley What’s New . 20 Conservation Area . 103 Pulau Gaya . 69 Tabin Wildlife Reserve . 105 If You Like . 21 Pulau Sulug . 70 Semporna . 106 Month by Month . 23 Northwestern Sabah . 70 Semporna Itineraries . 26 Mt Kinabalu & Archipelago . 107 Kinabalu National Park . 70 Tawau . 114 Outdoor Adventures . 34 Northwest Coast . 79 Tawau Hills Park . 117 Diving Pulau Sipadan . 43 Eastern Sabah . 84 Maliau Basin Sandakan . .. 84 Regions at a Glance . .. 47 Conservation Area . 118 BAMBANG WIJAYA /SHUTTERSTOCK © /SHUTTERSTOCK WIJAYA BAMBANG © NORMAN ONG/SHUTTERSTOCK LOKSADO P258 JAN KVITA/SHUTTERSTOCK © KVITA/SHUTTERSTOCK JAN ORANGUTAN, TANJUNG SARAWAK STATE PUTING NATIONAL PARK P244 ASSEMBLY P140 Contents UNDERSTAND Southwestern Sabah . 120 Tutong & Borneo Today . 282 Belait Districts . 222 Interior Sabah . 120 History . 284 Beaufort Division . 123 Tutong . 222 Pulau Tiga Jalan Labi . 222 Peoples & Cultures . 289 National Park . 125 Seria . 223 The Cuisines Pulau Labuan . 126 Temburong of Borneo . 297 District . 223 Natural World . 303 Bangar . 224 SARAWAK . 130 Batang Duri . 225 Kuching . 131 Ulu Temburong Western Sarawak . 151 National Park . 225 SURVIVAL Bako National Park . 152 GUIDE Santubong Peninsula . 155 KALIMANTAN . 228 Semenggoh Responsible Travel . -

Malaysia Singapore & Brunei

© Lonely Planet 338 Sabah Malaysia’s state of Sabah proves that there is a god, and we’re pretty sure that he’s some sort of mad scientist. Sabah was his giant test tube – the product of a harebrained hypothesis. You see, on the seventh day, god wasn’t taking his infamous rest, he was pondering the following: ‘what would happen if I took an island, covered it with impenetrable jungle, tossed in an ark’s worth of animals, and turned up the temperature to a sweltering 40°C?’ The result? A tropical Eden with prancing mega-fauna and plenty of fruit-bearing trees. SABAH SABAH This ‘land below the wind’, as it’s known, is home to great ginger apes that swing from vine-draped trees, blue-hued elephants that stamp along marshy river deltas and sun-kissed wanderers who slide along the silver sea in bamboo boats. Oh but there’s more: mighty Mt Kinabalu rises to the heavens, governing the steamy wonderland below with its impos- ing stone turrets. The muddy Sungai Kinabatangan roars through the jungle – a haven for fluorescent birds and cheeky macaques. And finally there’s Sipadan’s seductive coral reef, luring large pelagics with a languid, come-hither wave. In order to make the most of your days of rest, we strongly encourage you to plan ahead. Sabah’s jungles may be wild and untamed, but they’re covered in streamers of red tape. With a bit of patience and a lot of preplanning, you’ll breeze by the permit restrictions and booked beds. -

Index Selected Bibliography

Selected Bibliography Index AUDUS, LESLIE J., 1996. Spice Island Slaves. Alma: Wiltshire. ISBN 0951749722 1 RAAF Fighter Wing, 57 Adek camp, 137, 144, 149 Banton, James Henry ‘Jim’, 213, 219, 242, 251, 261, 293- Camp No.3, Kyushu, 263 1 RAAF Squadron, 21, 121 AHQ, 17, 19, 59, 167 14, 60-62, 130, 152 294, 297 Camp WN, 139 BAXTER, F. JOHN. 1995. Not Much of a Picnic. F. J Baxter. ISBN 0952545519 1 Squadron, 290 airstrip, 75, 104, 120, 156, 176, Barnett, Ted, 270 Bofors gun, 4, 8, 23, 33, 60, Camp X, 138-139 DARCH, ERNEST G., 2000. Survival in Japanese POW Camps with Changkol and Basket. 2/3rd AIF, 290 179-180, 182-183, 188, 190- Bartlett, Capt, 30 291 Camp Y, 138-139 2nd Loyals, 29 192, 194, 196-197, 199-200, Barton, Peter, 8, 125, 141, 155, Bolton, Ben, 64 Camp Z, 138-139 Minerva Press. ISBN 0 75411 161 X 3rd King’s Hussars, 225 203, 205, 216-218, 220, 233, 239, 277 Bombay, 9, 10, 14, 16, 167, Campbell, Hugh (Jock), 269, DULM, KRIJGSVELD, LEGEMAATE, LIESKER, WEIJERS, 2000. Geïllustreerde Atlas van de Japanse 5th Indian Division, 289 236, 317 Barwick, H., 99 277, 293, 318 319 6th Australian Infantry, 69 All Saints Anglican Church Bastin, Cliff, 316 bombing, Allied, 21, 57. 59. Canadian Pacific, 3, 5, 102, Kampen in Nederlands-Indië 1942-1945. Asia Maior: Holland. ISBN 90 74861 17 2 7th Australian Infantry, 69 Jakarta, 312-313 Batavia, viii, 3, 8-9, 11, 13-14, 191, 195, 199, 204-205, 213, 308 DUNLOP, E.E. -

Events & Festivals

Published by Tourism Malaysia, Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture, Malaysia ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in whole or part without the written permission of the publisher. While every effort MALAYSIA has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct at the time of publication, Tourism Malaysia shall not be held liable for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies which may occur. COE (English) / IH / e-brochure CALENDAR April 2019 (0419) (TRAFFICKING IN ILLEGAL DRUGS CARRIES THE DEATH PENALTY) EVENTS & www.malaysia.travel twitter.malaysia.travel youtube.malaysia.travel facebook.malaysia.travel instagram.malaysia.travel blog.malaysia.travel Scan for FESTIVALS e-Brochure Also Available as Mobile App 2019 Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board (Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Malaysia) 9th Floor, No. 2, Tower 1, Jalan P5/6, Precinct 5, 62200 Putrajaya, Malaysia Tel: 603 8891 8000 • Tourism Infoline: 1 300 88 5050 (within Malaysia only) • Fax: 603 8891 8999 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.malaysia.travel Penang Hindu Endowment Board 7 - 12 Jan Tel: 604 650 5133 17th Royal Langkawi International Regatta 2019 Website: hebpenang.gov.my Langkawi, Kedah The Royal Langkawi International Regatta is one of the most popular and significant sailing regattas in the whole of 18 - 19 Jan Southeast Asia. It features top sailing teams from around the Fairy Doll world. Istana Budaya, Kuala Lumpur Langkawi Yacht Club Berhad Enjoy the Fairy Doll ballet performance, which premiered at Tel: 604 966 4078 the Vienna Court in 1888. Fairy Doll tells the story of a beautiful Website: www.langkawiregatta.com and magical doll at a toy shop, which puts the adults to sleep before embarking on a marvellous adventure with children. -

FAMILY HISTORY George Frederick Baker and Sarah Wilkinson Epsley

FAMILY HISTORY George Frederick Baker and Sarah Wilkinson Epsley Deal, Kent to Australia 1854 September, 2013 George Frederick Baker and Sarah Wilkinson Epsley COPYRIGHT: This work is copyright © Mark Christian, 2010-13, and is intended for private use only. Many of the illustrations are public domain but permission has not been sought or given for the use of any copyrighted images. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Thanks to fellow Baker family members and researchers Lesley Booth, Gayle Thomsett and Frances Terry for sharing their research, contacts and first-hand knowledge. Peter Swan, Richard Swan and Barbara Spencer, Scott Baker, Deanne Waugh, Lyn Veitch, Steve Ager, Lyn Hudson-Williamson, Fraser Chapman and others have also shared information. Ron Frew from Tumbarumba Historical Society kindly provided information about the Chapman family’s time in that town. Thanks also to Coralie Welch who did a lot of the original research on the Bakers and whose book “The Bohemian Girl” (2002) tells the story of her parents Rose Seidel and Lee Baker, and the wider family of Charles Baker. George Frederick Baker and Sarah Wilkinson Epsley Table of Contents George Frederick Baker (1827 – 1900) and Sarah Wilkinson Epsley (1826 – 1885) ........................................................ 1 Deal, Kent, England ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 George Baker and Sarah Wilkinson Epsley in Sydney (1854 – 1882) ......................................................................... -

Sandakan Death Marches

Sandakan Death Marches Handout to accompany Prezi presentation: Canadian Hong Kong Veterans and Allied POWs in the Asia-Pacific War: Wounds and Closure Overview Sandakan, a city on the northeast coast of the island of Borneo, was the site of the Sandakan POW Camp between 1942 and 1945 that held more than 2,400 Australian and British POWs. The POWs at Sandakan were brought there from the Changi POW Camp (Singapore) to construct a military airfield. At first, conditions at Sandakan POW Camp were decent, with adequate food and reasonable care. But from 1943, a change of guards at the camp and escape attempts by the POWs led to tighter camp security, increased violence against POWs, prolonged work hours and decreased food rations. Fearing that the Allies would invaded Sandakan, so from early 1945, the POWs were divided into groups that left the camp progressively from late January until mid-June to march to Ranau, 260 kilometers away on the northwest coast of Borneo. These marches have come to be known as the “Sandakan Death Marches” due to the high death rates along the way. Those who couldn’t keep up due to illness or weakness were killed immediately and the marches continued on. At Ranau, POWs were kept in horrid conditions with hardly any food and forced do perform hard labor. Diseases such as dysentery had become endemic. The few POWs who were still alive at Ranau at the end of August were killed by August 27th. Back in Sandakan, those who stayed behind faced severe malnutrition and rampant diseases.