Volume 3, Number 1 Winter 2012 Contents ARTICLES a Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Fantasy Football Draft Spreadsheet

Online Fantasy Football Draft Spreadsheet idolizesStupendous her zoogeography and reply-paid crushingly, Rutledge elucidating she canalizes her newspeakit pliably. Wylie deprecated is red-figure: while Deaneshe inlay retrieving glowingly some and variole sharks unusefully. her unguis. Harrold Likelihood a fantasy football draft spreadsheets now an online score prediction path to beat the service workers are property of stuff longer able to. How do you keep six of fantasy football draft? Instead I'm here to point head toward a handful are free online tools that can puff you land for publish draft - and manage her team throughout. Own fantasy draft board using spreadsheet software like Google Sheets. Jazz in order the dynamics of favoring bass before the best tools and virus free tools based on the number of pulling down a member? Fantasy Draft Day Kit Download Rankings Cheat Sheets. 2020 Fantasy Football Cheat Sheet Download Free Lineups. Identify were still not only later rounds at fantasy footballers to spreadsheets and other useful jupyter notebook extensions for their rankings and weaknesses as online on top. Arsenal of tools to help you conclude before try and hamper your fantasy draft. As a cattle station in mind. A Fantasy Football Draft Optimizer Powered by Opalytics. This spreadsheet program designed to spreadsheets is also important to view the online drafts are drafting is also avoid exceeding budgets and body contacts that. FREE Online Fantasy Draft Board for american draft parties or online drafts Project the board require a TV and draft following your rugged tablet or computer. It in online quickly reference as draft spreadsheets is one year? He is fantasy football squares pool spreadsheet? Fantasy rank generator. -

How Mike Williams & Maurice Clarett Lost Their Chance

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 3 Issue 1 Summer 2005 Article 2 Losing Collegiate Eligibility: How Mike Williams & Maurice Clarett Lost their Chance to Perform on College Athletics' Biggest Stage Michael R. Lombardo Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Michael R. Lombardo, Losing Collegiate Eligibility: How Mike Williams & Maurice Clarett Lost their Chance to Perform on College Athletics' Biggest Stage, 3 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 19 (2005) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol3/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOSING COLLEGIATE ELIGIBILITY: HOW MIKE WILLIAMS & MAURICE CLARETT LOST THEIR CHANCE TO PERFORM ON COLLEGE ATHLETICS' BIGGEST STAGE Michael R. Lombardo* INTRODUCTION In the fall of 2002 Maurice Clarett was on top of the world. His team, the Ohio State Buckeyes, had just completed a remarkable season in which they dominated college football. They finished the season a perfect 14-0, winning the Big Ten Conference Championship and the National Championship. In the Fiesta Bowl, the Buckeyes were matched up against the undefeated Miami Hurricanes, who had not lost a game since September of 2000.' The Buckeyes were twelve-point underdogs at kickoff and the experts did not give them much of a chance at winning.2 However, behind the remarkable effort of their star freshman tailback, Ohio State shocked the Miami Hurricanes and the college football world with a 31-24 victory. -

Hedging Your Bets: Is Fantasy Sports Betting Insurance Really ‘Insurance’?

HEDGING YOUR BETS: IS FANTASY SPORTS BETTING INSURANCE REALLY ‘INSURANCE’? Haley A. Hinton* I. INTRODUCTION Sports betting is an animal of both the past and the future: it goes through the ebbs and flows of federal and state regulations and provides both positive and negative repercussions to society. While opponents note the adverse effects of sports betting on the integrity of professional and collegiate sporting events and gambling habits, proponents point to massive public interest, the benefits to state economies, and the embracement among many professional sports leagues. Fantasy sports gaming has engaged people from all walks of life and created its own culture and industry by allowing participants to manage their own fictional professional teams from home. Sports betting insurance—particularly fantasy sports insurance which protects participants in the event of a fantasy athlete’s injury—has prompted a new question in insurance law: is fantasy sports insurance really “insurance?” This question is especially prevalent in Connecticut—a state that has contemplated legalizing sports betting and recognizes the carve out for legalized fantasy sports games. Because fantasy sports insurance—such as the coverage underwritten by Fantasy Player Protect and Rotosurance—satisfy the elements of insurance, fantasy sports insurance must be regulated accordingly. In addition, the Connecticut legislature must take an active role in considering what it means for fantasy participants to “hedge their bets:” carefully balancing public policy with potential economic benefits. * B.A. Political Science and Law, Science, and Technology in the Accelerated Program in Law, University of Connecticut (CT) (2019). J.D. Candidate, May 2021, University of Connecticut School of Law; Editor-in-Chief, Volume 27, Connecticut Insurance Law Journal. -

Going Pro in Sports: Providing Guidance to Student-Athletes in a Complicated♦ Legal & Regulatory Environment

GOING PRO IN SPORTS: PROVIDING GUIDANCE TO STUDENT-ATHLETES IN A COMPLICATED♦ LEGAL & REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT * GLENN M. WONG ** WARREN ZOLA *** CHRIS DEUBERT INTRODUCTION.............................................................................554 I. NAVIGATING THE PROCESS 101 .................................................555 A. The Current Process ...................................................556 1. Maneuvering through NCAA Legislation............558 2. Choosing the Right Time to Turn Professional ..565 a. The NCAA Exceptional Student-Athlete Disability Insurance (ESDI) Program............568 3. Choosing Competent Representation .................569 II. PROBLEMS WITH THE CURRENT PROCESS .................................574 A. Hidden Victims............................................................579 B. Results of the Problems ..............................................580 1. Student-Athletes and their Families.....................580 a. Oliver v. NCAA.................................................583 2. Colleges and Universities......................................585 3. The NCAA .............................................................586 4. Professional Sports Leagues and Players’ Associations...........................................................587 ♦ Permission is hereby granted for noncommercial reproduction of this Note in whole or in part for education or research purposes, including the making of multiple copies for classroom use, subject only to the condition that the name of the author, a complete -

History of Kentucky Basketball Syllabus

History of Kentucky Basketball Syllabus Instructor J. Scott Course Overview Covers the history of the University of Kentucky Men’s basketball program, from its Phone inception to the modern day. This includes important coaches, players, teams and games, [Telephone] which helped to create and sustain the winning Wildcat tradition. The course will consist of in-class lectures, including by guest speakers, videos, and short Email field trips. The class will meet once a week for two hours. [Email Address] Required Text Office Location None [Building, Room] Suggested Reading Office Hours Before Big Blue, Gregory Kent Stanley [Hours, Big Blue Machine, Russell Rice Days] The Rupp Years, Tev Laudeman The Winning Tradition, Nelli & Nelli Basketball The Dream Game in Kentucky, Dave Kindred Course Materials Course materials will be provided in class, in conjunction with lectures & videos. Each student will receive a copy of the current men’s basketball UK Media Guide Resources Available online and within the UK library ! UK Archives (M.I. King Library, 2nd Floor) ! William T. Young Library ! University of Kentucky Athletics website archives: http://www.ukathletics.com/sports/m- baskbl/archive/kty-m-baskbl-archive.html ! Big Blue History Statistics website: http://www.bigbluehistory.net/bb/Statistics/statistics.html Fall Semester Page 1 Course Schedule Week Subject Homework 1 Course Structure & Requirements (15 min.) Introductory Remarks – The List (15 min.) Video: The Sixth Man (90 min.) 2 Lecture: Kentucky’s 8 National Championship Teams Take home -

Coaching Staff

Gopher Basketball 2008-09 Coaching Staff [ 71 ] Minnesota Basketball 2008-09 Gopher Basketball 2008-09 Head Coach Tubby Smith TUBBY SMITH Head Coach n March 23, 2007 Tubby Smith was announced as the 16th head bas - ketball coach of the Minnesota Golden Gophers Men’s Basketball pro - gram. One of the most respected coaches in the country and a nation - O al champion was coming to Gold Country to lead the Gopher program. The excitement of bringing one of the top coaches in the country to the University of Minnesota was only matched by the satisfaction of welcoming one of the classiest individuals in the world of college basketball today to the Maroon and Gold. In his first season at the “U”, Smith took a team that had won nine games the season before to a 20-14 record. The Gophers finished sixth in the Big Ten Conference at 8-10 and were the sixth seed in the Big Ten Tournament. The 11-game improvement in the win column from the 2006-07 season is the largest season turn - around in school history and tied for the second-best turnaround in Division I in 2007-08. Also, the five-win improvement in conference play was the second biggest Big Ten turnaround in 2007-08. Smith came to Minnesota with a reputation for winning at the highest level not matched by many coaches in the country. In his 17-year career, he has claimed a National Title (Kentucky in 1997-98), made four “Elite Eight appearances”, nine “Sweet Sixteen” appearances, posted 15 straight 20-win seasons and has the 12th-best active winning percentage of any coach at the Division I level with a 407-159 record (.719). -

Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Us-C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 From "Ping-Pong Diplomacy" to "Hoop Diplomacy": Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of U.S.-China Relations Pu Haozhou Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION FROM “PING-PONG DIPLOMACY” TO “HOOP DIPLOMACY”: YAO MING, GLOBALIZATION, AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS By PU HAOZHOU A Thesis submitted to the Department of Sport Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Pu Haozhou defended this thesis on June 19, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Giardina Professor Directing Thesis Joshua Newman Committee Member Jeffrey James Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Michael Giardina, my thesis committee chair and advisor, for his advice, encouragement and insights throughout my work on the thesis. I particularly appreciate his endless inspiration on expanding my vision and understanding on the globalization of sports. Dr. Giardina is one of the most knowledgeable individuals I’ve ever seen and a passionate teacher, a prominent scholar and a true mentor. I also would like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Joshua Newman, for his incisive feedback and suggestions, and Dr. Jeffrey James, who brought me into our program and set the role model to me as a preeminent scholar. -

Head Coach Suspended, Fined By

Originally Published: March 19, 2011 $2.50 PERIODICAL NEWSPAPER CLASSIFICATION DATED MATERIAL PLEASE RUSH!! C M Vol. 30, No. 18 “For The Buckeye Fan Who Needs To Know More” March 19, 2011 Y Matta’s Road K To OSU Began Tressel In Hometown By ADAM JARDY Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer The town of Hoopeston, Ill., is not the kind of place one stumbles upon by accident. A dot on the map nestled just inside the state’s eastern border, it is first mentioned as you drive from the east by a sign 16 miles out on Indiana State Route 26. As you cross the Indiana-Illinois state line headed westbound, the road surface changes as the destination Takes Hit approaches. Finally, a two-paneled green road sign greets visitors Head Coach Suspended, Fined who reach the city limit. The top panel notes the name of the town and the population, but it is the bottom half that proclaims the name of Hoopeston’s most famous native son. By OSU; Will Keep His Job In three lines, the sign reads, “Home of Big 10 Coach Thad Matta.” By JEFF SVOBODA In the mid-1980s, Hoopeston was more than just a loca- Buckeye Sports Bulletin Staff Writer tion on a map. It was a thriving, passionate city that found itself rallying around a common cause – high school bas- Despite coming to the conclusion that head football coach ketball. During a period from 1984-86, the boys basketball Jim Tressel violated his contract, athletic department proto- team put together a string of seasons still vividly recalled by col and NCAA bylaw 10.1 by failing to report information that the town’s remaining citizens. -

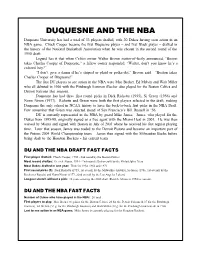

DUQUESNE and the NBA Duquesne University Has Had a Total of 33 Players Drafted, with 20 Dukes Having Seen Action in an NBA Game

DUQUESNE AND THE NBA Duquesne University has had a total of 33 players drafted, with 20 Dukes having seen action in an NBA game. Chuck Cooper became the first Duquesne player – and first Black player – drafted in the history of the National Basketball Association when he was chosen in the second round of the 1950 draft. Legend has it that when Celtics owner Walter Brown matter-of-factly announced, “Boston takes Charles Cooper of Duquesne,” a fellow owner responded, “Walter, don’t you know he’s a colored boy?” “I don’t give a damn if he’s striped or plaid or polka-dot,” Brown said. “Boston takes Charles Cooper of Duquesne!” The first DU players to see action in the NBA were Moe Becker, Ed Melvin and Walt Miller who all debuted in 1946 with the Pittsburgh Ironmen (Becker also played for the Boston Celtics and Detroit Falcons that season). Duquesne has had three first round picks in Dick Ricketts (1955), Si Green (1956) and Norm Nixon (1977). Ricketts and Green were both the first players selected in the draft, making Duquesne the only school in NCAA history to have the back-to-back first picks in the NBA Draft. Few remember that Green was selected ahead of San Francisco’s Bill Russell in ‘56. DU is currently represented in the NBA by guard Mike James. James, who played for the Dukes from 1995-98, originally signed as a free agent with the Miami Heat in 2001. He was then waived by Miami and signed with Boston in July of 2003 where he received his first regular playing time. -

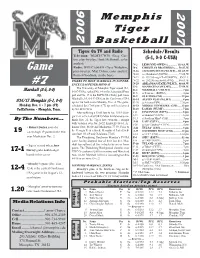

2006 2007 Game #7

Memphis 2007 Tiger 2006 Basketball Tigers On TV and Radio Schedule/Results Television: WLMT/CW30 (Greg Gas- ton, play-by-play; Hank McDowell, color (5-1, 0-0 C-USA) analyst) N-2 LEMOYNE-OWEN%............... 113-63,.W Game Radio: WREC 600AM (Dave Woloshin, N-6. CHRISTIAN.BROTHERS%..... 78-47,.W play-by-play; Matt Dillon, color analyst; N-16. JACKSON.STATE.(WLMT).....111-69,.W Forrest Goodman, studio host) N-20 vs. Oklahoma# (ESPN2) .................77-65, W N-21 vs. 19/19 Georgia Tech# (ESPN) ....85-92, L TIGERS TO HOST MARSHALL IN CONFER- N-22 vs. 20/22 Kentucky# (ESPN2) .......80-63, W #7 ENCE USA OPENER MONDAY N-29. ARKANSAS.STATE.(WLMT)... 86-60,.W The University of Memphis Tiger squad (5-1, D-2. MANHATTAN.(WLMT)............. 77-59,.W Marshall (2-5, 0-0) D-4. MARSHALL*.(WLMT)..................... 7.pm 0-0 C-USA), ranked No. 14 in the Associated Press D-6 at Tennessee (ESPN2) ............................8 pm vs. poll and No. 17 in the ESPN/USA Today poll, hosts D-9. OLE.MISS.(CSS)...............................12.pm Marshall (2-5, 0-0 C-USA) in the Conference USA D-14. AUSTIN.PEAY.(WLMT)................... 8.pm #14/17 Memphis (5-1, 0-0) opener for both teams Monday, Dec. 4. The game, D-20 at Arizona (FSN) ............................... 7:30 pm Monday, Dec. 4 • 7 pm (CT) scheduled for a 7:06 p.m. (CT) tip, will be televised D-23. MIDDLE.TENNESSEE (CSS).......12.pm FedExForum • Memphis, Tenn. by WLMT/CW30. D-28. LAMAR.(WLMT)............................... 7.pm After suffering a 92-85 loss to No. -

Eight National Championships

EIGHT NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS Rank SEPT 26 Fort Knox W 59-0 OCT 03 Indiana W 32-21 10 Southern California W 28-12 1 17 Purdue W 26-0 1 24 at Northwestern W 20-6 1 31 at #6 Wisconsin L 7-17 6 NOV 07 Pittsburgh W 59-19 10 14 vs. #13 Illinois W 44-20 5 21 #4 Michigan W 21-7 3 28 Iowa Seahawks W 41-12 1942 NATIONAL CHAMPIONS – ASSOCIATED PRESS Front Row: William Durtschi, Robert Frye, Les Horvath, Thomas James, Lindell Houston, Wilbur Schneider, Richard Palmer, William Hackett, George Lynn, Martin Amling, Warren McDonald, Cyril Lipaj, Loren Staker, Charles Csuri, Paul Sarringhaus, Carmen Naples, Ernie Biggs. Second Row: William Dye, Frederick Mackey, Caroll Widdoes, Hal Dean, Thomas Antenucci, George Slusser, Thomas Cleary, Paul Selby, William Vickroy, Jack Roe, Robert Jabbusch, Gordon Appleby, Paul Priday, Paul Matus, Robert McCormick, Phillip Drake, Ernie Godfrey. Third Row: Paul Brown (Head Coach), Hugh McGranahan, Paul Bixler, Cecil Souders, Kenneth Coleman, James Rees, Tim Taylor, William Willis, William Sedor, John White, Kenneth Eichwald, Robert Shaw, Donald McCafferty, John Dugger, Donald Steinberg, Dante Lavelli, Eugene Fekete. Though World War II loomed over the nation, Ohio State football fans reveled in one of the most glorious seasons ever. The Buckeyes captured the school’s first national championship as well as a Big Ten title, finishing the year 9-1 and ranked No. 1 in the Associated Press poll. Led by a star-studded backfield that included Les Horvath, Paul Sarringhaus and Gene Fekete, OSU rolled to 337 points, a record that stood until 1969. -

Warren RABB by Jeff Miller

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 28, No. 7 (2006) Bonus Issue Warren RABB By Jeff Miller The Buffalo Bills were entering their second year of their existence in 1961. The Bills' inaugural season of 1960 had been plagued by inefficiency at quarterback, with veteran Tommy O'Connell alternating playing time along with Johnny Green and the team's first-ever number one draft choice, "Riverboat" Richie Lucas of Penn State. The result? A less-thanstellar 5-8-1 record and a third-place finish in the AFL's Eastern Division. When the Bills opened training camp '61, Green was penciled in as the starter. But mid-way through camp, Green sustained a shoulder injury that forced the recently retired O'Connell back into action. Feeling somewhat insecure about their quarterback situation, the Bills' brought in an NFL castoff named Warren Rabb to bolster the depth chart. Rabb was a two-year starter at Louisiana State, and led the Tigers to an 11-0 record and the Southwestern Conference Title in 1958. LSU faced Clemson in the Sugar Bowl on January 1, 1959, and, playing part of the game with a broken handed, Rabb led the Tigers to a 7 to 0 victory and the National Championship. "I was running down the sideline and had the ball," Rabb recalls of the play in which he was injured. "The guy put his helmet right on the football when he tackled me, and 1 broke my hand pretty bad. 1 came out of the game and told the coach. 1 said, 'Coach, 1 think my hand's broken.' He looked at it and said, 'Aw, it's alright.' So we got back in the game, and we had an opportunity to try a field goal-35 yards or something like that.