Regional Muslim Politics in Multan Under the British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATCH UPDATES and TIME TABLE of Pakistan Super League 2021 S.NO

MATCH UPDATES AND TIME TABLE Of Pakistan Super League 2021 S.NO. Date Time (IST) Match Venue 1. February 20 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Quetta Gladiators Karachi 2. February 21 2:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Multan Sultans Karachi 3. February 21 7:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Multan Sultans Karachi 4. February 22 7:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 5. February 23 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 6 February 24 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Islamabad United Karachi 7. February 26 2:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 8. February 26 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 9. February 27 2:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Multan Sultans Karachi 10. February 27 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Islamabad Karachi United 11. February 28 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Lahore Qalandars Karachi 12. March 1 7:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 13. March 3 2:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Peshawar Zalmi Karachi 14. March 3 7:30 PM Quetta Gladiators National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 15. March 4 7:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Islamabad Karachi United 16 March 5 7:30 PM Multan Sultans vs National Stadium, Karachi Kings Karachi 17. March 6 2:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Quetta Karachi Gladiators 18. March 6 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi v National Stadium, Lahore Qalandars Karachi 19. -

List of Approved Clinical Trial Sites Under the Bio-Study Rules 2017

Government of Pakistan Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations & Coordination DRUG REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF PAKISTAN TF Complex, Sector G-9/4, Islamabad ****** “SAY NO TO CORRUPTION” Updated till: 09th April 2021. LIST OF APPROVED CLINICAL TRIAL SITES UNDER THE BIO-STUDY RULES 2017. S.No License Clinical Trial CTS Address Approved Study Approved Status Remarks Date of . Number Site for Drug. in C.S.C. Expiration Clinical of licence. Trial 01. CTS- M/s Holy Family Gynae Unit-I & II, Holy Women-II Tranexamic 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 17th July 0001 Hospital, Family Hospital, Said Pur Clinical Acid Meeting. 18th July 2019. 2019. Rawalpindi Road. Rawalpindi Studies. Held on 17th July 2019. 02. CTS- M/s Ghouri Plot C-76, Sector 31/5, End-TB, Multi Drug 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 09th October 0002 Clinic, The Indus Opposite Darussalam MDR TB Meeting. 10th October 2019. Hospital, Karachi Society, Korangi Crossing, Clinical Held on 17th 2019. Karachi-75190, Pakistan. Trial July 2019. 03. CTS- Aga Khan Stadium Road, P.O. Box Not Multiple 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 09th October 0003 University 3500, Karachi 74800, Specific Clinical Meeting. 10th October 2022. Hospital, Clinical Pakistan. Trials Held on 17th 2019. Trial Unit (CTU), July 2019. Karachi 04. CTS- Shaukat Khanum 7-A, Khayaban-e-Firdousi, Not Multiple 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 20th 0004 Memorial Cancer Block R3 M.A Johar Town, Specific Clinical Meeting. 21st November November Hospital & Lahore. Trials Held on 17th 2019. 2019. Research Center, July 2019. Lahore. Page 1 of 10 05. CTS- Department of Near Chandni Chowk, Women-II Tranexamic 4th CSC Approved. -

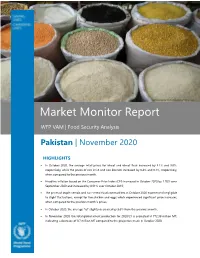

Market Monitor Report

Food Commodities Photo WFP/Aman ur Rehman khan Market Monitor Report WFP VAM | Food Security Analysis Pakistan | November 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • In October 2020, the average retail prices for wheat and wheat flour increased by 5.4% and 3.8%, respectively, while the prices of rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati increased by 0.4% and 0.1%, respectively, when compared to the previous month; • Headline inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased in October 2020 by 1.70% over September 2020 and increased by 8.91% over October 2019; • The prices of staple cereals and non-cereal food commodities in October 2020 experienced negligible to slight fluctuations, except for live chicken and eggs which experienced significant price increases, when compared to the previous month’s prices; • In October 2020, the average ToT slightly decreased by 3.6% from the previous month; • In November 2020, the total global wheat production for 2020/21 is projected at 772.38 million MT, indicating a decrease of 0.7 million MT compared to the projection made in October 2020. Market Monitor | Pakistan | November 2020 Page 2 Headline inflation Headline inflation based on the Consumer Table 1: CPI (%) Price Index (CPI) increased in October Food Non-Food 2020 by 1.70% over September 2020 and Period Urban Rural Urban Rural increased by 8.91% over October 2019. 2020 YoY MoM YoY MoM YoY MoM YoY MoM The food/non-food values of CPI September 12.4 3.0 15.8 3.8 5.0 0.2 7.2 0.3 disaggregated at urban and rural areas is October 13.9 2.8 17.7 4.3 3.6 0.3 5.8 0.5 presented in Table 1. -

15 the Regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan

ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1 THE REGIONS OF SIND . 15 THE REGIONS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN, MULTAN AND KASHMIR: THE HISTORICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC SETTING* N. A. Baloch and A. Q. Rafiqi Contents THE RULERS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN AND MULTAN (750–1500) ....... 298 The cAbbasid period and the Fatimid interlude (mid-eighth to the end of the tenth century) ...................................... 298 The Period of the Ghaznavid and Ghurid Sultanates (eleventh and twelfth centuries) . 301 The era of the local independent states ......................... 304 KASHMIR UNDER THE SULTANS OF THE SHAH¯ MIR¯ DYNASTY ....... 310 * See Map 4, 5 and 7, pp. 430–1, 432–3, 437. 297 ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1 The cAbbasid period Part One THE RULERS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN AND MULTAN (750–1500) (N. A. Baloch) From 750 to 1500, three phases are discernible in the political history of these regions. During the first phase, from the mid-eighth until the end of the tenth century, Sind, Baluchis- tan and Multan – with the exception of the interlude of pro-Fatimid ascendency in Mul- tan during the last quarter of the tenth century – all remained politically linked with the cAbbasid caliphate of Baghdad. (Kashmir was ruled, from the eighth century onwards, by the local, independent, originally non-Muslim dynasties, which had increasing political contacts with the Muslim rulers of Sind and Khurasan.) During the second phase – the eleventh and twelfth centuries – all these regions came within the sphere of influence of the powers based in Ghazna and Ghur. During the third phase –from the thirteenth to the early sixteenth century – they partly became dominions of the Sultanate of Delhi, which was in itself an extension into the subcontinent of the Central Asian power base. -

Report of Marketing Channel Survey (Mangoes) in Rahim Yar Khan and Multan

Policy and Institutional Reforms to Improve Horticultural Markets in Pakistan (ADP/2014/043) DRAFT REPORT 03/18 Preliminary Report of Marketing Channel Survey (Mangoes) in Rahim Yar Khan and Multan. Information Collected from Growers and Contractors. Nauman Ejaz Assistant Professor International Islamic University Islamabad [email protected] Abstract This reports preliminary results and observations on the supply chain and marketing issues including relationships between the various stakeholders (farmers, contractors, retailers, etc.), their respective profit margins and the stages through which mango flows from the farm to the consumer (marketing channels). It is based on information collected from interviews and discussions with a sample of selected mango growers and (pre-harvest) contractors in Rahim Yar Khan and Multan districts, two of the largest and most famous mango producing regions in Pakistan, during the peak mango season in July 2018. The preliminary findings suggest that the dominant system of mango marketing is the one where growers enter into pre-harvest contracts with contractors, who then sell their produce through commission agents. Often but not always entering into pre-harvest contracts and advance payment arrangements with them - and sometimes with exporters, is a stable system because it is attractive to all parties as it provides efficient methods for risk sharing and risk management. The relationships between contracting parties are informal but typically long term. But the system does not seem to provide incentives to growers to enhance quality or productivity, or acquire better skills and expertise, though there is some limited evidence of a quality premium being received by the contractors. As many growers as well as contractors consider mango as a part time occupation and a source of supplemental income, they are also unwilling to exert much effort on direct sales to wholesalers or exporters. -

33422717.Pdf

1 Contents 1. PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. OVERVIEW OF THE CULTURAL ASSETS OF THE COMMUNITIES OF DISTRICTS MULTAN AND BAHAWALPUR ................................................................... 9 3. THE CAPITAL CITY OF BAHAWALPUR AND ITS ARCHITECTURE ............................ 45 4. THE DECORATIVE BUILDING ARTS ....................................................................................... 95 5. THE ODES OF CHOLISTAN DESERT ....................................................................................... 145 6. THE VIBRANT HERITAGE OF THE TRADITIONAL TEXTILE CRAFTS ..................... 165 7. NARRATIVES ................................................................................................................................... 193 8. AnnEX .............................................................................................................................................. 206 9. GlossARY OF TERMS ................................................................................................................ 226 10. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................. 234 11. REPORTS .......................................................................................................................................... 237 12 CONTRibutoRS ............................................................................................................................ -

Market Monitor Report

Food Commodities Photo WFP/Aman ur Rehman khan Market Monitor Report WFP VAM | Food Security Analysis Pakistan | July 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • The prices of staple cereals and non-cereal food commodities in June 2021 experienced negligible to significant fluctuations when compared to the previous month’s prices. • In June 2021, the average retail prices negligibly increased for wheat (0.8%) and wheat flour (0.6%) from May 2021. Moreover, the price of rice Irri-6 negligibly decreased by 0.2% while the price of rice Basmati slightly increased by 1.5% from the previous month. • In June, compared to the previous month, slight increases were noted in the average retail prices of eggs, pulse Masoor and cooking oil along with negligible increases for Sugar, vegetable ghee and pulse Mash. Moreover, a significant decrease was noted in the price of live chicken and a slight decrease in the price of pulse Moong, while the price of pulse Gram remained unchanged when compared to the previous month. • Headline inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) decreased in June 2021 by 0.24% over May 2021 and increased by 9.7% over June 2020. • In June 2021, the average ToT negligibly decreased by 0.1% from the previous month. • In July 2021, the total global wheat production for 2021/22 is projected at 792.40 million MT, indicating a production decrease of 2.04 million MT compared to the projection made in June 2021. Market Monitor | Pakistan | July 2021 Page 2 Headline inflation Headline inflation based on the Table 1 CPI (%) Consumer Price Index (CPI) decreased Food Non-Food in June 2021 by 0.24% over May 2021 Period Urban Rural Urban Rural and increased by 9.7% over June 2020. -

Panel Hospitals

LAHORE HOSPITALS SERIAL NAME OF HOSPITAL ADDRESS TELEPHONE # NO. 1 Akram Eye Hospital Main Boulevard Defence Road Lahore. 042-36652395-96 2 CMH Hospital CMH Lahore Cantt., Lahore 042-6699111-5 3 Cavalry Hospital 44-45, Cavalry Ground Lahore Cantt. 042-36652116-8 4 Family Hospital 4-Mozang Road Lahore 042-37233915-8 5 Farooq Hospital 2 Asif Block, Main Boulevard Iqbal Town, Lahore 042-37813471-5 6 Fauji Foundation Bedian Road Lahore Cantt. 042-99220293 7 Gulab Devi Hospital Ferozepur Road Lahore 042-99230247-50 8 Ittefaq Hospital Near H. Block Model Town, Lahore 042-35881981-8 9 Masood Hospital 99, Garden Block, Garden Town, Lahore 042-35881961-3 10 Prime Care Hospital Main Boulevard Defence Lahore 042-36675123-4 11 Punjab Institute of Cardiology Jail Road Lahore. 042-99203051-8 12 Punjab Medical Centre 5, Main boulevard, Jail Road, Lahore 042-35753108-9 13 Laser Vision Eye Hospital 95-K, Model Town, Lahore 042-35868844-35869944 14 Sarwat Anwar Hospital 2, Tariq block Garden Town, Lahore 042-35869265-6 15 Shalimar Hospital Shalimar Link Road, Mughalpura Lahore 042-36817857-60, 111205205 16 Rasheed Hospital Branch 1, Main Boulevard Defence Lahore 042-336673192-33588898 Branch 2, Garden Town Lahore. 17 Orthopedic Medical Complex & Hospital Opposite Kinnarid College Jail Road, Lahore 042-37551335-7579987 18 National Hospital & Medical Centre 132/3, L-Block, LCCHS Lahore Cantt. 042-35728759-60 F: 042-35728761 19 Army Cardiac Centre Lahore Cantt. 20 Dental Aesthetics Clinic 187-Y, Block D.H.A., Lahore – Pakistan 042-35749000 21 Sana Dental Aesthetics 153-DD, CCA Phase-IV, DHA Lahore 042-37185861-2 CONSULTANTS 1 Cavalry Dental Clinic 26, Commercial Area, Cavalry Ground Lahore 042-36610321 2 Dr. -

Micronutrients Status of Mango (Mangifera Indica) Orchards in Multan Region, Punjab, Pakistan, and Relationship with Soil Properties

Open Agriculture 2020; 5: 271–279 Research Article Niaz Ahmed*, Ayta Umer, Muhammad Arif Ali, Javed Iqbal, Muhammad Mubashir, Abdul Ghaffar Grewal, Beenish Butt, Muhammad Khalid Rasheed, Usman Khalid Chaudhry Micronutrients status of mango (Mangifera indica) orchards in Multan region, Punjab, Pakistan, and relationship with soil properties https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2020-0033 Thus, there is a serious need to improve the chemical received August 3, 2019; accepted May 19, 2020 properties of the soil, and the proper dose of micronu- ffi Abstract: Mango orchards in Pakistan are deficient in soil trients should be applied every season for su cient micronutrients. Multan is one of the prime regions for supply throughout the growing cycle of mango in and mango production in Pakistan; therefore, this study was around the Multan region. conducted to evaluate the micronutrient status of mango Keywords: chemical properties, mango, micronutrients, orchards in the Multan region. Soil samples from four Multan region, orchards different depths (0–30, 30–60, 60–90, and 90–120 cm) and leaf samples were collected from thirteen different locations of Multan. Depth-wise variations in the micro- nutrient status and the levels of pH, EC, CEC, SOM, and 1 Introduction CaCO3 were determined. All data collected from the field and laboratory work of mango orchards under study were Pakistan is one of the best mango growing countries, - analyzed statistically by applying the RCBD design. It was which exports high quality mango fruits globally. Pakistan ( observed that pH and EC of soil under study were is ranked at fourth position in the mango production The e ) significantly higher in upper depths when compared with Daily Records 2017 . -

Village List of Multan Division , Pakistan

Cel'.Us 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-19 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST PUNJAB Multan Division OFFICE Of THE PROVINCIAL · .. ·l),ITENDENT CENSUS, J~ 1952 ,~ :{< 'AND BAHAWALPUR, P,IC1!iR.. 10 , , FOREWOf~D This Village Ust has been prepared from the material collected in con nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be available and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showinz its area to the nearest square mile, and its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsll th~ Revenue Kanungo ho/qas are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo halqa and the remaining villages comprising the halqas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column a. Rakhs (tree plantations) and other similar area,. even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast nurY'lbcrs have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries, to be inhabited. -

Famous Governors of Multan Under the Sikh Regime in Punjab

Review Article Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud Volume 2 Issue 2 - November 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ahmad Ali DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2018.02.555584 Famous Governors of Multan Under the Sikh Regime in Punjab Ahmad Ali1*, Shahid Hasan Rizvi2, Khizar Hayat3 and Muhammad Akbar4 1Lecturer at Govt. Degree College Mailsi, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan 2Chairman Department of History, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan 3P.S.T. at G.P.S. Kotla Dilbar, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan 4S.S.S. at G.H.S.S 53 M, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Submission: July 21, 2018; Published: November 05, 2018 *Corresponding author: Ahmad Ali, Lecturer at Govt. Degree College Mailsi and PhD Scholar, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Abstract Maharaja Ranjit Singh had numerous Hindu Officials and Courtiers at Lahore Durbar because he needed to utilize their services in civilian setup to grow and build his Kingdom. Undoubtedly, he required to inject the soul of rivalry, chastisement and proficiency in his various officials specifyingand courtiers that so some that ofhe these could were merge unfortunate his place and and would disappointed have the with capacity their topast enlarge services, his Realmso they without could get much any trouble.status, either By utilizing a General them, or ahe clerk, also onproved the ground the secular of legitimacy. scenario of Among his Empire. them, He,following according pioneers to his werenecessities, appointed fully the utilized Governors the competence in Multan ofwhom these played Hindu a Courtiers. vital role Itin will politics, be worth civil as well as military administration, economics, agriculture, irrigation and land revenue etc. -

“The Problem of Human Trafficking Cannot Be Ad- Dressed by a Single

Issue 10 January - March 2017 This issue “The problem of human 13,000 Pakistanis deported from European countries over the past 4 years P.2 trafficking cannot be ad- dressed by a single stake- Arrests of Human Traffickers and holder, whether public, Migrant Smugglers P.3 private or non-govern- Policy Level Interventions Undertaken mental. In order to be ef- by FIA P.4 fective and to provide a Launch of UNODC Country sustainable solution to the Programme II (2016-19) P.5 issue, engagement must be multi-stakeholder in Quarterly Data Analysis P.6 approach and focused on partnerships”. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Note: Statistics for this newsletter have been provided by the FIA Human Trafficking Migrant smuggling& Newsletter 13,000 Pakistanis deported from European countries over the past 4 years Over 13,000 Pakistanis were deported from (IATF) members. More than 1,800 raids were various European countries over the past four conducted during November and December years. The number of deportees is gradually 2016 during which 1,500 suspects from Pun- decreasing due to effective measures being jab, and 890 from Islamabad Capital Territory, taken by the FIA to control human trafficking. were arrested. Some of these arrests made The majority of passengers were deported for by the FIA during the quarter are mentioned reasons of overstay, loss of passport, entry below. refusal, illegal entry, voluntary return, revo- cation of residence permit, rejection of asy- lum case, non-payment of taxes, and/or fake/ forged documents. Starting from 2013, a total of 5,279 immi- grants were deported that year from Europe- an countries.