View 1999 Catalog As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18Th Annual Eastern Conference of the Timber Framers Guild

Timber Framers Guild 18th Annual Eastern Conference November 14–17, 2002, Burlington, Vermont The Timber Framer’s Panel Company www.foardpanel.com P.O. Box 185, West Chesterfield, NH 03466 ● 603-256-8800 ● [email protected] Contents FRANK BAKER Healthy Businesses. 3 BRUCE BEEKEN Furniture from the Forest . 4 BEN BRUNGRABER AND GRIGG MULLEN Engineering Day to Day ENGINEERING TRACK . 6 BEN BRUNGRABER AND DICK SCHMIDT Codes: the Practical and the Possible ENGINEERING TRACK . 8 RUDY CHRISTIAN Understanding and Using Square Rule Layout WORKSHOP . 13 RICHARD CORMIER Chip Carving PRE-CONFERENCE WORKSHOP . 14 DAVID FISCHETTI AND ED LEVIN Historical Forms ENGINEERING TRACK . 15 ANDERS FROSTRUP Is Big Best or Beautiful? . 19 ANDERS FROSTRUP Stave Churches . 21 SIMON GNEHM The Swiss Carpenter Apprenticeship . 22 JOE HOWARD Radio Frequency Vacuum Drying of Large Timber: an Overview . 24 JOSH JACKSON Plumb Line and Bubble Scribing DEMONSTRATION . 26 LES JOZSA Wood Morphology Related to Log Quality. 28 MICHELLE KANTOR Construction Law and Contract Management: Know your Risks. 30 WITOLD KARWOWSKI Annihilated Heritage . 31 STEVE LAWRENCE, GORDON MACDONALD, AND JAIME WARD Penguins in Bondage DEMO 33 ED LEVIN AND DICK SCHMIDT Pity the Poor Rafter Pair ENGINEERING TRACK . 35 MATTHYS LEVY Why Buildings Don’t Fall Down FEATURED SPEAKER . 37 JAN LEWANDOSKI Vernacular Wooden Roof Trusses: Form and Repair . 38 GORDON MACDONALD Building a Ballista for the BBC . 39 CURTIS MILTON ET AL Math Wizards OPEN ASSISTANCE . 40 HARRELSON STANLEY Efficient Tool Sharpening for Professionals DEMONSTRATION . 42 THOMAS VISSER Historic Barns: Preserving a Threatened Heritage FEATURED SPEAKER . 44 Cover illustration of the Norwell Crane by Barbara Cahill. -

Carving Newsletter February 2021 Final Version-2

FEBRUARY 2021 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Hello Carvers, I want to invite you to a special member meeting on April 21st at 7:00 PM (online). Te agenda includes officially changing the name from the Western Woodcarvers Association to the Oregon Carvers Guild, adding language to become a 501c3 charitable nonproft, revising the bylaws and electing officers. To register, click here. We want to honor the 48 year legacy of the Western Woodcarvers Association and continue using the State’s legal framework but change the name. To do this we need to make a one sentence name change to the Articles of Incorporation and fle the amendment. Tis is easy, but we will make other necessary changes while we are at it. Particularly we will add boilerplate language so we can become a 501c3 nonproft, the strongest and best type. Right now we are a generic c7 nonproft which provides no beneft to donors. It will take another six months to get IRS approval after that. Members need to approve these changes. While we are at it, we are going to ask you to approve new bylaws to refect our planned organization and add protection for directors and officers. Te language for these will be voluminous but necessary. Quite boring for most of us to wade through, but quite necessary. Finally, we will vote on officers for the next fscal year, hear about our progress and plans and answer questions. If you have a desire to serve on the board, or volunteer to help in any way, please let me know. -

Library-By-Media.Pdf

Card# Title Author Media Group 168 SHAKER BAND SAW PROJECTS DUGINAKE/MORRIS BOOK band saw 156 BANDSAW HANDBOOK VOL #2 (dup 131) DUGINSKE BOOK band saw 369 BANDSAW WORKSHOP BENCH REF. DUGINSKE, MARK BOOK band saw 314 SHOP TIPS bandsaw RODALE BOOKS BOOK band saw 138 BUILDING BEAUTIFUL BOXES/BANDSAW VENTURA, LOIS KEENER BOOK band saw 52 THE ART OF THE BAND SAW DUGINSKE, MARK BOOK bandsaw 133 MILTI USE COLLAPSIBLE BASKETS LONGABAUGH RICK & KAREN BOOK baskets 155 COLLAPSIBLE BASKET PATTERNS LONGABOUGH R& K BOOK baskets 227 THE BIRD FEEDER BOOK BOSWELL, THOM BOOK birds 389 EASY TO MAKE BIRD FEEDERS CAMPBELL, SCOTT D BOOK birds 416 MAKING BACKYARD BIRD HOUSES CORTWRIGHT AND POKRIOTS BOOK birds 147 MAKING FANCY BIRDHOUSES & FEEDERS D BOOK birds 620 BIRD HOUSES AND FEEDERS MEISEL, PAUL BOOK birds 229 BEASTLY ABODES-BIRDS, BATS, BUTTERFLY NEEDHAM,BOBBE BOOK birds 621 MAKING FANCY BIRD HOUSES AND FEEDERS SELF, CHARLES BOOK birds 346 BOATBUILDING CHAPELLE, HOWARD BOOK boat 471 BUILDING A STRIP CANOE GILPATRICK,GIL BOOK boat 428 STRIPPERS GUIDE/CANOE BLDNG HAZEN,DAVID BOOK boat 197 CLINKERBOAT BUILDING LEATHER,JOHN BOOK boat 478 STRIP-BUILT BOATS MILLER,LEW BOOK boat 427 CANOE CRAFT MOORES, TED-MOHR,MERILYN BOOK boat 722 BOAT MODELING PAYSON, DYNAMITE BOOK boat 472 BUILDING LAPSTRAKE CANOES SIMMONS, WALTER BOOK boat 474 LAPSTRAKE BOATBUILDING SIMMONS, WALTER BOOK boat 391 BUILDING THE CANOE STELMAK,JERRY BOOK boat 470 WOOD AND CANVAS CANOE STELMOK, JERRY BOOK boat 476 BUILDING THE HERRESHOFF DINGHY THOMAS, BARRY BOOK boat 475 LOFTING VAITSES,ALLAN H BOOK boat 450 BUILD A BOAT WOOD BOAT MAGAZINE BOOK boat 477 BOAT BUILDING WOODS WOODENBOAT MAGAZINE BOOK boat 429 BLDNG BOB'S SPECIAL CANOE BOOK boat 422 HOW TO DESIGN CANOES BOOK boat 43 MAKING WOOD BOXES W/ BAND SAW CRABB BOOK boxes 325 FINE DEC. -

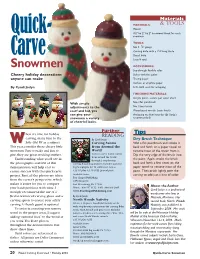

Quick Carve Snowmen

2038_Snowmen_RD.QXD 10/12/04 3:04 PM Page 20 Materials MATERIALS: & TOOLS Wood: 1 Quick- 4 ⁄2" by 2" by 2" basswood block for each snowman TOOLS: 7 No. 3 ⁄8" gouge 1 Carving knife with a 1 ⁄4"-long blade Carve Detail knife 1mm V tool Snowmen ACCESSORIES: See-through flexible ruler Cheery holiday decorations Stylus with fine point anyone can make Tracing paper Carbon or graphite paper By Cyndi Joslyn Soft cloth used for antiquing FINISHING MATERIALS: Acrylic paint - colors per color chart With simple No.6 flat paintbrush adjustments to the No.1 liner brush scarf and hat, you Waterbased varnish (satin finish) can give your Antiquing medium/retarder (Jo Sonja’s snowmen a variety recommended) of cheerful looks. Further Tips hen it’s time for holiday READING carving, many turn to the By Cyndi Josyln Dry Brush Technique WWJolly Old Elf as a subject. Carving Santas Wet a flat paintbrush and stroke it This year, consider these cheery little from Around the back and forth on a paper towel to snowmen. Fun to make and fun to World remove most of the water from it. give, they are great stocking stuffers. Learn to carve festive Santas Dip the very edge of the brush into from around the world Understanding what you’ll see in through 3 step-by-step the paint. Again stroke the brush the photographs and text of this carving & painting projects. Includes patterns back and forth a few times on the demonstration will help a lot to & photographs for 12 additional Santas. -

September 2018

THE WILDFOWLER SEPTEMBER 2018 A PUBLICATION OF THE ATLANTIC WILDFOWL HERITAGE MUSEUM AND THE BACK BAY WILDFOWL GUILD Back Bay Wildfowl Guild Memories Thomas C. Green March 1, 1935 – August 26, 1994 Tom, better known as “Shane”, a nickname he was tagged with as a young child, loved working in his home studio on Loren Crescent in the Cavalier Manor neighborhood of Portsmouth, Virginia. A home he shared with his wife Sylvia where they raised two boys. He enjoyed carving decoys, painting flat art landscapes and scenes of wild ducks and birds. He also enjoyed etching. The variety of the mediums allowed him to express himself without his art becoming boring and mundane. Shane called his passion for art a sickness and therapy all rolled up together. Shane was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. Shortly after his birth his family moved to Portsmouth, VA where he attended Mount Hermon Elementary School and graduated from I. C. Norcom High School. He then attended Virginia State College where he obtained degrees in Chemistry and Accounting. In 1958 Shane joined the United States Army as a Second Lieutenant resigning his commission as a Captain in 1963. In April of 1990 he retired as an Auditor for the United States Navy after a stellar 25 year career where he earned the Navy’s Meritorious Civilian Service Award. Throughout his career as an auditor his was required to travel. He traveled up and down the East and West coasts of the United States, to Japan, Cuba, Europe, and Hawaii. All the while maintaining an avid interest in a variety of art forms. -

2019 Design in Wood Accepted List by Last Name

2019 Design In Wood Accepted List By Last Name WEN Last Name First Name Division Class and Class Description Title Accepted 13DBD3 Ababaf Daryoush 1101 Design In Wood 014 - Veneering/Marquetry - Art Wildflowers Accepted 5D9482 Ababaf Daryoush 1101 Design In Wood 014 - Veneering/Marquetry - Art Turtle Accepted 99E52E Ababaf Daryoush 1101 Design In Wood 014 - Veneering/Marquetry - Art Goldfish Accepted 53E0EA Albertson David 1101 Design In Wood 010 - Model Building - Not to Scale 1930 Ford Accepted 9567F6 Amick James 1101 Design In Wood 018 - Wood Turning - Embellished/Mixed Media Myrtle Pearl Accepted D3084C Amick James 1101 Design In Wood 018 - Wood Turning - Embellished/Mixed Media Walnut Burl Pearl Accepted D9E0F0 Anderson Karen J 1101 Design In Wood 026 - Scroll Saw - Fretwork - Pierced & Unpierced Fancy Fish Accepted DF401F Appelquist Paul 1101 Design In Wood 006 - Chairs - Furniture Made for Seating Sleigh seat Accepted E4AC30 Atangan Patrick 1101 Design In Wood 006 - Chairs - Furniture Made for Seating Eliptical Sofa Accepted 1658DD Ault Sally 1101 Design In Wood 018 - Wood Turning - Embellished/Mixed Media Spire Accepted 203F9D Ault Sally 1101 Design In Wood 016 - Wood Turning - Face Work: Perpendicular to the ways of the lathe Natural Edge Bowl Accepted 58AED5 Ault Sally 1101 Design In Wood 016 - Wood Turning - Face Work: Perpendicular to the ways of the lathe Blowin' in the Wind Accepted B515AB Avery Joe 1101 Design In Wood 005 - Art Furniture Surfboard Table Accepted F17968 Barrientos Ivan 1101 Design In Wood 026 - Scroll Saw -

Living with Wood to the Participants and the General Public

REDISCOVERING WOOD: THE KEY TO A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE ART AND JOY OF WOOD BANGALORE, INDIA 19 OCTOBER – 22 OCTOBER 2011 PROCEEDINGS PART 1- CONFERENCE OVERVIEW The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107598-2 (print) E-ISBN 978-92-5-107599-9 (PDF) © FAO 2013 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence- request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Home Craft Course : Pennsylvania German Wood Carving Ebook, Epub

HOME CRAFT COURSE : PENNSYLVANIA GERMAN WOOD CARVING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK W J McAllister | 48 pages | 30 Mar 2007 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781432557898 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Home Craft Course : Pennsylvania German Wood Carving PDF Book What a beautiful color! After seeing the ten foot version of Eric's double eagle tree chainsaw carving, the client asked if he could create a somewhat smaller version. The mass was scheduled in the early morning hours of Christmas Day, following the last shift on Christmas Eve. There are no gimmicks, just European craft tradition solidly rooted in a lifetime of training and experience, taught by a true master woodcarver if you know me you know I do not use that word lightly, and I believe that is what sets this school apart from many of the other schools out there. If you want to rent tools we offer that as well. His work can be found in nearly every state, including Alaska and Hawaii, and on at least 6 continents. He captures the essence of a single moment in the daily life of his subject. I have produced abstract forms as well as anatomical figures. Read about eating disorder treatment here. Shop Now. Reply 6 years ago on Introduction. Unless you were a doctor for trees or something of that sort. How long wood carving tool holds the sharp edge of a blade. Contact: Artist: Garry King, wood sculptor "Garry King has worked and loved wood all his life. For those flying in we are located 50 minutes north of Logan Airport in Boston. -

Effective Recycling and Use of Wood Carving Waste in Wood Industry

IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN: 2278-1684,p-ISSN: 2320-334X PP 20-30 www.iosrjournals.org Effective Recycling and Use of Wood Carving Waste in Wood Industry Jijin I1, Rinitha P1 1(Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering Thalassery/ CUSAT, INDIA) Abstract: Composites based on natural fibre reinforcement have generated wide research and engineering interest in the last few decades due to their small density, high specific strength, low cost, light weight, recyclability and biodegradability and has earned a special category of green composite. This article reviews the reports based on wooden waste using different fibre as fillers and reinforcements. Various processing methods and conditions like compression moulding, heat treatments are used in the composites productions. Manufacturing industry produces large amount of waste throughout the year. Most of the time these waste ends up in landfills disturbing environmental, economical and social life cycle. Sustainable development is a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs; and can be considered as one of the solution to solve manufacturing waste problem. Sustainable design, proper use and reuse of the resources will make wood and other industries more economical and green. Process of recycling waste includes storage, sorting, collection, transportation, recycling and disposing. For recycling wood waste, the water vapour explosion (WVE) process was developed. In this process wood materials were exploded from within by the force of water vapour generated by compression by high pressure and temperature and evaporation of the internal moisture and thus they are separated into small wood elements. -

Frame Making: Carving, Gilding and Finishing

2016 BEYOND 25 YEARS OF SKILLS ENHANCEMENT 2014 George Alexander Foundation International Fellowship Frame Making: Carving, Gilding and Finishing Reuben Rich An ISS Institute Fellowship sponsored by The George Alexander Foundation ISS Institute Inc JULY 2016 © ISS Institute T 03 9347 4583 Level 1 E [email protected] 189 Faraday Street www.issinstitute.org.au Carlton Vic W AUSTRALIA 3053 Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne Published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute July 2016 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report or any links therein, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. i. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report details the international experience of the Fellow in his quest to acquire knowledge and insight into the artisanal methodology, procedure, history and artistry of traditional picture-frame making. The Fellow travelled to Istanbul in Turkey, and to Florence, Rome and the enchanting small town of Moie in Italy. He visited galleries, museums, the Vatican and a dozen artisan framing workshops and studios during this Fellowship program. -

Blue Heron Tavern Pyrography .Pdf

Pyrography Worksheet by Lora S Irish ArtDesignsStudio.com Blue Heron Tavern Worksheet Variable temperature tool systems This Blue Heron Tavern Worksheet assumes that reader Variable temperature systems have a dial thermostat that has some proficiency with pyrography as an art form allows you to control how cool or hot your tip is. You and focuses only on the tonal value steps for this can adjust the temperature setting quickly making it easy particular project. to control your tonal values in your project. If you are just beginning your craft of wood burning our This style has two types of pens - the fixed tip pen where blog, LSIrish.com has many free, step-by-step, in-depth the tip is permanently set in the hand grip and the tutorials and projects that will help you master the skills interchangeable pen where different wire tips can be of this favorite art. used with the hand grip. There are many excellent burning systems available to Supplies the hobbyist, which manufacture you chose depends on your budget, your pen style preferences, and what is available to you locally or online. 14” x 11” basswood oval plaque 220- and 320-grit sandpaper printed pattern graphite paper ink pen for tracing transparent tape variable temperature wood burning unit ball tip pen flat shading tip pen spear point detailing pen medium brown acrylic craft paint hot glue and hot glue gun ½ pound twisted sea grass acrylic spray sealer If you are looking to upgrade your current unit you might consider the Optima, the Colwood Detailer, or the Versa-Tool. -

![Wood Carving – 5 Days Jacob Henry � 5/18/2015 7:55 PM Comment [1]: Do You Have All Your Materials for All Your Classes? Handicraft, 2015](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5468/wood-carving-5-days-jacob-henry-5-18-2015-7-55-pm-comment-1-do-you-have-all-your-materials-for-all-your-classes-handicraft-2015-4125468.webp)

Wood Carving – 5 Days Jacob Henry � 5/18/2015 7:55 PM Comment [1]: Do You Have All Your Materials for All Your Classes? Handicraft, 2015

Wood Carving – 5 Days Jacob Henry ! 5/18/2015 7:55 PM Comment [1]: Do you have all your materials for all your classes? Handicraft, 2015 Monday: Requirements 1A, 2B Jacob Henry ! 5/18/2015 7:30 PM Comment [2]: See Art where I talk about 1. Do the following: ‘Monday Stuff’ a. Explain to your counselor the hazards you are most likely to encounter while wood carving, and what you should do to anticipate, help prevent, mitigate, or lessen these hazards. Personal Cautions: Jacob Henry ! 5/18/2015 7:30 PM - Don’t carve when tired- get a good night’s sleep Comment [3]: How is this information being delivered? It’s okay if it’s just a lecture - Distracted- focus while carving, knives aren’t toys but you’ll need to list that. - Carve where you have permission- not on your parent’s kitchen table Knife Cautions: -safe is sharp, dull is dangerous (skid off wood into hand) - keep tools clean and kept in safe places - don’t pass knives over other people -carve on the table, not your lap -carve away from your body and face - Small stokes give you more control over the knife and project - don’t muscle if you find yourself having to cut smaller chunk or get different knife Environment Cautions: - make sure to have good lighting and sturdy sitting location -plenty of room, so not to bump anyone - use clamps for control when cutting smaller pieces 2. Do the following: a. Earn the Totin' Chip recognition. (attached pamphlet) Jacob Henry ! 5/18/2015 6:15 PM b.