Manfred Honeck, Conductor Narek Hakhnazaryan, Cello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neujahrskonzert 2012 Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum

Neujahrskonzert 2012 Musikalische Schätze aus Russland und Wien Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg Dirigent: Hansjörg Angerer Freitag, 6. Jänner 2012 11.00 Uhr Großes Festspielhaus, Salzburg Musikalische Schätze aus Russland und Wien Das Neujahrskonzert 2012 der Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg unter der Leitung ihres Chefdirigenten Hansjörg Angerer stellt mit klangvollen Walzern, Ouvertüren, Tänzen und Märschen die Verbindung der Wiener Musik zu Russland in den Mittelpunkt. Johann Strauss Sohn, unbestrittener König der Wiener Tanzmusik des ausgehenden 19. Jahr- hunderts, verbrachte mit seinem Orchester in den Jahren 1856 bis 1865 eine ganze Reihe von Sommern in Russland, wo er auch eine ansehnliche Zahl seiner Werke komponierte und erstmals zur Aufführung brachte. Wenn das wienerische Kolorit in seinem Oeuvre auch stets präsent ist, so versteht Strauss es doch genauso meisterhaft, Anklänge anderer Kulturen – wie eben an ein oftmaliges russisches Gastland – oder auch Stimmungen von Natur, Wald und Jagd in seine Musik einfließen zu lassen. Russland verfügt über ein ungemein großes und reichhaltiges musikalisches Erbe. Russische Musik wird gerne mit den Attributen ‚schwermütig’, ‚traurig’ und ‚melancholisch’ verbunden, was zweifellos eine nicht haltbare Einengung des emotionalen Spektrums bedeutet. Die russischen Meister jedoch konnten wie kaum andere gerade diese Emotionen in großer Innigkeit spürbar machen. Über den Wiener Walzer wurde geschrieben, dass er niemals wirklich lustig sei, da auch stets melancholische Zwischentöne in ihm zu finden seien. Johann Strauss‘ Liebe zu Russland mit seinen langjährigen sommerlichen Engagements in St. Petersburg legten es somit nahe, diese musikalischen Welten in einem Konzert miteinander zu verschmelzen. Bekannte und neu zu entdeckende Meisterwerke von Komponisten wie Glinka, Mussorgski, Tschaikowski, Chatschaturjan und Schostakowitsch treffen im Neujahrskonzert der Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg auf Kostbarkeiten der leichten Muse von Johann Strauss und populären Zeitgenossen. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Salonorchester.Pdf

Das Programm des seit 2002 zur Boosey & Hawkes-Gruppe gehörenden Musikverlags Anton J. Benjamin bietet, neben zahlreichen Werken des ‘ernsten’ Repertoires, eine große Fülle von Schätzen für Salonorchester. Dabei handelt es sich gleichermaßen um Originalkompositionen wie um Bear- beitungen beliebter klassischer Werke. Stöbern Sie hier in dieser nahezu unerschöpflichen Fundgrube! (Für die Suche nach weiteren Werken im Programm von Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock benutzen Sie bitte unseren Online-Katalog unter www.boosey.de/Katalog.) Hinweise zur Benutzung des PDF-Katalogs: Diese Ausgabe des Benjamin-Salonorchester-Kataloges nennt neben dem Komponisten, Titel und Bearbeiter auch die Spieldauer (soweit bekannt), die im Verlagsarchiv vorhandene Besetzung und den Preis der Standard-Ausgabe. Die Standard-Ausgabe (Spalte „Stand“) ist in der Regel die Salonorchester-Besetzung mit Piano- Direktion, Harmonium (Akkordeon), Violine-Direktion (doppelt), Violine obligat, Cello, Kontrabaß, Flöte, Oboe, Klarinette, Trompete, Posaune III und Schlagzeug (abgekürzt: SO). In vielen Fällen allerdings ist keine Oboe vorgesehen bzw. nur als Ergänzerstimme erhältlich (Abkürzung: SOo). Wenn darüber hinaus die jeweilige Ausgabe weniger Stimmen als oben aufgeführt enthält (z.B. kein Schlagzeug, kein Blech oder überhaupt keine Bläser) bzw. - in einigen wenigen Fällen - vermutlich unvollständig ist, so ist die Abkürzung für die Besetzungsangabe in Klammern gesetzt. Von der normalen Salonorchester- Besetzung gänzlich abweichende Spezial-Arrangements sind mit „§“ bezeichnet. Ergänzerstimmen (Spalte „Erg“) gibt es in vielen Fällen für „kleines“ und für „großes“ Orchester (Abkürzung: K bzw. G). Normalerweise besteht das „kleine Orchester“ aus Piano-Direktion, Violine-Dir. (doppelt), Violine II, Viola, Cello, Kontrabaß, Flöte, Oboe, Klarinette I und II, Fagott, Horn I und II, Trompete I und II, Posaune und Schlagzeug. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

Repertoire MGK 19 20 © Dacapo Austria

1 R e p e r t o i r e Matthias Georg Kendlinger Komponist und Dirigent Sinfonisches Repertoire Beethoven, Ludwig van: Sinfonien Nr. 2 op. 36 · 3 op. 55 · 5 op. 67 · 7 op. 92 · 9 op. 125 · Klavierkonzert Nr. 2 op. 19 · Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus op. 43 (Ouvertüre) · Violinromanze Nr. 2 op. 50 · Coriolan op. 62 (Ouvertüre) · Egmont op. 84 (Ouvertüre) · Zur Namensfeier op. 115 (Ouvertüre) Brahms, Johannes: Sinfonie Nr. 2 op. 73 Bruckner, Anton: Sinfonie Nr. 4 WAB 104 · Sinfonie Nr. 7 WAB 107 Dvorák, Antonín: Sinfonie Nr. 9 op. 95 „Aus der Neuen Welt“ · Humoreske op. 101 Nr. 7 Enescu, George: Rumänische Rhapsodie op. 11 Nr. 2 Grieg, Edvard: Peer Gynt-Suite Nr. 2 op. 55: Der Brautraub Kendlinger, Matthias Georg: Sinfonische Dichtung op. 2 „Der verlorene Sohn“ · Sinfonie Nr. 1 op. 4 „Manipulation“ · Meditative Dichtung op. 6 „Heilung“ · Klavierkonzert Nr. 1 op. 7 „Larissa“ · Cellokonzert Nr. 1 op. 8 „Unser Vater“ · Sinfonie Nr. 2 op. 9 „Die Österreich-Ukrainische“ · Sinfonie Nr. 3 op. 10 „Menschenrechte“ · Violinkonzert Nr. 1 op. 11 „Galaxy“ Mahler, Gustav: Sinfonie Nr. 2 „Auferstehungssinfonie“ · Sinfonie Nr. 5 Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus: Sinfonie Nr. 1 KV 16 · Sinfonie Nr. 34 KV 338 · Sinfonie Nr. 35 KV 385 „Haffner“ · Sinfonie Nr. 40 KV 550 Ravel, Maurice: Boléro Schubert, Franz: Sinfonie Nr. 4 D 417 „Tragische“ · Sinfonie Nr. 5 D 485 · Sinfonie Nr. 7 D 759 „Unvollendete“ Schumann, Robert: Kinderszenen op. 15: Träumerei Strauss, Richard: Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche op. 28 · Also sprach Zarathustra op. 30 (Prelude) Tschaikowsky, Pjotr Iljitsch: Nocturne op. 19/4 · Klavierkonzert Nr. -

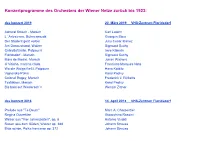

Programme.Pdf

Konzertprogramme des Orchesters der Wiener Netze zurück bis 1923: das konzert 2019 20. März 2019 VHS-Zentrum Floridsdorf Admiral Stosch - Marsch Carl Latann L´ Arlesienne, Bühnenmusik Georges Bizet Der Student geht vorbei Juliu Cesar Ibanez Am Donaustrand, Walzer Sigmund Suchy Csárdásfürstin, Potpourri Imre Kálmán Floridsdorf - Marsch Sigmund Suchy Mars de Medici, Marsch Johan Wichers O Vitinho, marcha chula Francisco Marques Neto Wo die Wolga fließt, Potpourri Hans Kolditz Vajnorska Polka Karol Padivy Colonel Bogey, Marsch Frederick J. Ricketts Textilakov, Marsch Karol Padivy Bis bald auf Wiederseh´n Wenzel Zittner das konzert 2018 14. April 2018 VHS-Zentrum Floridsdorf Prelude aus "Te Deum" Marc A. Charpentier Regina Ouvertüre Gioacchino Rossini Winter aus "Vier Jahreszeiten", op. 8 Antonio Vivaldi Rosen aus dem Süden, Walzer op. 388 Johann Strauss Bitte schön, Polka francaise op. 372 Johann Strauss Der Vogelhändler, Potpourri Carl Zeller Triglav Marsch op. 72 Julius Fucik Harry Potter, Filmmusik John Williams Westside Story, Potpourri Leonard Bernstein Mixed Pickles Max Leemann Maxglaner Zigeunermarsch Tobias Reiser Für Österreichs Ehr´ Marsch Josef Lassletzberger Böhmische Musikanten, Polka Rudolf Lamp Dort tanzt Lulu, Walzer Will Meisel Faszination Blasmusik 22. Oktober 2017 Konzerthaus Triglav, Marsch op. 72 Julius Fucik Verträumte Melodien, Potpourri Hans Kolditz Tanzen möcht´ ich, Walzer Imre Kálmán das konzert 2017 22. April 2017 VHS-Zentrum Floridsdorf Abendgebet aus "Nachtlager in Granada" Conradin Kreutzer Eine Nacht in Venedig, Ouvertüre Johann Strauss Stephanie Gavotte, op. 312 Alphons Czibulka Erinnerung an Franz Schubert, Potpourri Johann Kliment Das liegt bei uns im Blut, Polka mazur op. 374 Carl M. Ziehrer Loreley-Rhein - Klänge, Walzer op. 154 Johann Strauss, Vater Per aspera ad astra, Marsch Ernst Urbach Khevenhüller Marsch Anton Fridrich The lion sleeps tonight Weiss / Creatore / Kampstra Fernando / Thank you for the music Benny Anderson / Björn Ulvaeus Persischer Marsch, op. -

Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: Historical Background and Conductor's Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2019 Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: Historical Background and Conductor's Guide Jennifer Bruton University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Bruton, Jennifer, "Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: Historical Background and Conductor's Guide" (2019). Dissertations. 1727. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1727 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHANN STRAUSS II’S DIE FLEDERMAUS: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE by Jennifer Jill Bruton A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Jay Dean, Committee Chair Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe Dr. Gregory Fuller Dr. Christopher Goertzen Dr. Michael A. Miles ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Jay Dean Dr. Jay Dean Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School December 2019 COPYRIGHT BY Jennifer Jill Bruton 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Students pursuing graduate degrees in conducting often have aspirations of being high school or college choir or band directors. Others want to lead orchestra programs in educational or professional settings. Sadly, many colleges and universities do not have systems in place that provide avenues for those choosing this career path. -

Die Fledermaus History

Johann Strauss’ Die Fledermaus HISTORY Premiere April 5, 1874 at the Theater an der Wien, Vienna, with the following cast: Alfred, Hr. Rüdinger; Adele, Esther Charles-Hirsch; Rosalinde, Marie Geistinger; Gabriel von Eisenstein, Jani Szika; Dr. Falke, Ferdinand Lebrecht; Frank, Karl Adolf Friese; Prince Orlofsky, Irma Nittinger. North American Premiere November 21, 1874, in New York at the Stadt Theater Last Performed by Washington National Opera September, 2003 in DAR Constitution Hall, featuring Heinz Fricke conducting and Lotfi Mansouri directing with the following cast: Alfred, Jesús Garcia; Adele, Maki Mori; Rosalinde, June Anderson; Gabriel von Eisenstein, Wolfgang Brendel; Dr. Blind, Robert Baker; Dr. Falke, Peter Edelmann; Frank, John Del Carlo; Prince Orlofsky, Elena Obraztsova; Ida, Tammy Roberts; Frosch, Jason Graae; Solo Dancers, Lisa Gillespie and Harlan Bengel. Johann Strauss’ Operas and Operettas Die Lustigen Weiber von Wien (never produced) Indigo und die Vier Ruber, February 10, 1871; Theater-an-der-Wien Der Karneval in Rom, March 1, 1873; Theater-an-der-Wien Die Fledermaus, April 5, 1874; Theater-an-der-Wien Cagliostro in Wien, February 27, 1875; Theater-an-der-Wien Prinz Methusalem, January 3, 1877; Carl Theater Blinde Kuh, December 18, 1878; Theater-an-der-Wien Das Spitzentuch der Königin, October 1, 1880; Theater-an-der-Wien Der Lustige Krieg, November 25, 1881; Theater-an-der-Wien Eine Nacht in Venedig , October 3, 1883; Freidrich-Wilhalmstrasse Theater, Berlin Der Zigeunerbaron, October 24, 1885; Theater-an-der-Wien Simplizius, December 17, 1887, Theater-an-der-Wien Ritter Pasman, January 10, 1893; Hofoperntheater, Wein Fürstin Ninetta, January 10, 1893; Theater-an-der-Wien Waldmeister, December 4, 1895; Theater-an-der-Wien Washington National Opera www.dc-opera.org 202.295.2400 · 800.US.OPERA . -

Konzertchronik Haydnorchester Eisenstadt

Konzertchronik Haydnorchester Eisenstadt 1965 - 2014 Bearbeitung: Roland Graschitz, Katrin Gstöttenbauer, Stefanie Rechnitzer und Christian Weisz Stand: Jänner 2014 Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Abt. 7 der burgenländischen Landesregierung Inhaltsverzeichnis Jahr Seite Jahr Seite 1965 1 1990 36 1966 1 1991 38 1967 2 1992 40 1968 3 1993 42 1969 3 1994 44 1970 4 1995 47 1971 4 1996 49 1972 5 1997 52 1973 5 1998 54 1974 6 1999 56 1975 6 2000 58 1976 7 2001 62 1977 9 2002 64 1978 10 2003 69 1979 11 2004 72 1980 12 2005 75 1981 13 2006 78 1982 15 2007 81 1983 18 2008 84 1984 21 2009 86 1985 25 2010 91 1986 28 2011 92 1987 31 2012 94 1988 33 2013 96 1989 34 2014 99 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite i Konzertchronik, Haydnorchester Eisenstadt KONZERTE 1965 30. Mai Haydn-Gedächtniskonzert, Festsaal des Bundesrealgymnasiums Eisenstadt Solistin: Dorothea Gradwohl, Violine Leitung: Eduard Ehrenreich 19. Dez. Adventkonzert, Festsaal des Bundesrealgymnasiums Eisenstadt Ausführende: Haydnchor des Volksbildungswerks Eisenstadt Kammerorchester Joseph Haydn Eisenstadt Leitung: Otto Strobl 1966 19. Mai Musikalische Vesper, Redemptoristenkirche Oberpullendorf Leitung: Stefan Kocsics 2. Juni Haydn-Gedächtniskonzert, Haydnsaal Schloss Esterházy Leitung: Eduard Ehrenreich 2. Juli Kammerkonzert, Bad Sauerbrunn Leitung: Eduard Ehrenreich 28. Aug. Konzert anlässlich der Feierlichkeiten „40 Jahre Stadt Neusiedl am See“ Leitung: Eduard Ehrenreich 29. Okt. Konzert, Güssing Leitung: Eduard Ehrenreich 1965/1966 Seite 1 von 102 Konzertchronik, Haydnorchester Eisenstadt 1967 26. Feber Konzert, Neusiedl am See Leitung: Eduard Ehrenreich 12. März Konzert, Oberpullendorf J. Haydn: „Die sieben Worte des Erlösers am Kreuze“ Ausführende: Mittelburgenländischer Lehrerchor Kammerorchester Joseph Haydn Eisenstadt Leitung: Stefan Kocsics 25. -

Strauss Johann

STRAUSS JOHANN Johann Strauss (figlio) (Neubau, 25 ottobre 1825 – Vienna, 3 giugno 1899) è stato un compositore e direttore d'orchestra austriaco. 1 Riconosciuto come uno dei più importanti musicisti di ogni epoca, Strauss è principalmente noto per la sua attività di compositore di musica da ballo e di operette. Figlio primogenito del compositore Johann Strauss padre, Johann Strauss è stato il più celebre membro di una famiglia di musicisti che, per quasi un secolo, dominò le scene musicali viennesi. La sua fama è legata soprattutto ai suoi valzer, alcuni dei quali ancora oggi celeberrimi, come Wiener Bonbons, Künstlerleben, Geschichten aus dem Wienerwald, Wein, Weib und Gesang, Wiener Blut, Rosen aus dem Süden, Frühlingsstimmen, Kaiser-Walzer e, quello che viene considerato il valzer più famoso di tutti i tempi, An der schönen blauen Donau (Sul bel Danubio blu); per questo motivo a Strauss è stato universalmente riconosciuto l'appellativo di "Re del Valzer". Fra le altre danze della sua lunga produzione (la lista delle sue opere comprende circa 500 composizioni fra valzer, polke, marce e quadriglie) vale la pena di menzionare Annen-Polka, Leichtes Blut, Éljen a Magyar!, Pizzicato Polka (scritta a quattro mani col fratello Josef), Auf der Jagd! e la Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka. Strauss seppe distinguersi anche nel campo dell'operetta arrivando a comporne sedici nell'arco di poco meno di trent'anni. Il suo più grande successo l'ottenne con Die Fledermaus (Il Pipistrello) che, ancora oggi, è considerata il culmine di quel periodo musicale che venne rinominato Goldene Operettenära (Era d'oro dell'operetta viennese). Suoi fratelli furono i compositori Josef ed Eduard Strauss. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 129, 2009-2010

^ Silk twill scarves. Boston 320 Boylston Street (617) 482-8707 Hermes.com 1 HERMES PARIS <c VERMES, LIFE AS A Table of Contents | Week 17 15 BSO NEWS 23 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 25 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 28 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 31 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAM 32 FROM THE MUSIC DIRECTOR Notes on the Program 35 Richard Strauss "Don Quixote" 47 Johann, Johann II, and Josef Strauss 57 To Read and Hear More... Solo Artists 61 Lynn Harrell 63 Steven Ansell 65 SPONSORS AND DONORS 72 FUTURE PROGRAMS 74 SYMPHONY HALL EXIT PLAN 75 SYMPHONY HALL INFORMATION program copyright ©2010 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photograph by Charles Gauthier BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617) 266-1492 bso.org EMC? 8 where information lives EMC is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The global icon of artistic virtuosity known as the Boston Symphony Orchestra is also the world's largest orchestral organization. The BSO understands the critical role information plays in its business, and turns to information infrastructure solutions from EMC to help keep its intricate operations a miracle of performance. We're proud to help the BSO bring the power of information to life— information that illuminates what's possible and that can move the world forward. Learn more at www.EMC.com. S\ EMC, EMC, and where information lives are registered trademarks of EMC Corporation. All other trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. © Copyright 2008 EMC Corporation. -

Mira & Stella Disc Catalog (PDF)

Mira & Stella Tune List 7/25/2020 NOTE: Numbering is identical for all sizes of Mira & Stella discs, with some sizes of Stella discs having a prefix to these numbers. No. Title Song Type Composer 1 My Queen Waltz Waltz Coote, Jr. 2 Blue Danube Waltz Joh Strauss, Jr 3 Waves of the Danube Waltz Ivanovici 4 Faust Waltz Gounod 5 Wine Spirits Waltz (Le Petit Bleu) Lecocq 6 After the Ball Waltz Kiefert 7 Estudiantina Waltz Waldteufel 8 Wine, Women and Song Waltz Joh Strauss, Jr 9 I Am a Rover (from Chimes of Normandy or les Cloches de Corneville) Waltz Planquette 10 Nanon, valse d' Anne Genee 11 Invitation to the Dance Waltz Weber 12 Roses from the South Waltz Joh Strauss, Jr 13 The Daughter of Madame Angot Waltz Lecocq 14 The Wave Waltz Metra 15 Do I Love You? Waltz Rosenzweig 16 Jumping-Jack Waltz Foerster 17 Espana Waltz Waldteufel 18 Wiener Blut Waltz Joh Strauss, Jr 19 A Night in Venice Waltz Joh Strauss, Jr 20 Violetta Polka Joh Strauss, Jr 21 Carmen Polka Bizet 22 Polka des Fleurs Ziehrer 23 Always Gay Polka Faust 24 From Heart to Heart Mazurka Andree 25 Excelsior Mazurka Marenco 26 My Sweetheart Mazurka Komzak 27 La Czarina Mazurka L Ganne 28 A Life for the Czar Mazurka Glinka 29 Don Cesar March Dellinger 30 Boccaccio March Suppe 31 Gasparonne March Millocker 32 Under the Double Eagle March Wagner 33 Prayer (from William Tell) Rossini 34 Standchen Serenade (from Boccaccio) Suppe 35 Serenade (from Don Juan) Mozart 36 In unserer Heimat (from ll Troratore) Duet Verdi 37 The Last Rose of Summer (from Martha) Flotow 38 Bridal Chorus (from