Crimes — Forgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Senior Management Mens Rea: Another Stab at a Workable Integration of Organizational Culpability Into Corporate Criminal Liability

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Article 11 2011 The Senior Management Mens Rea: Another Stab at a Workable Integration of Organizational Culpability into Corporate Criminal Liability George R. Skupski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation George R. Skupski, The Senior Management Mens Rea: Another Stab at a Workable Integration of Organizational Culpability into Corporate Criminal Liability, 62 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 263 (2011) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol62/iss1/11 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 1/5/2012 3:02:17 PM THE SENIOR MANAGEMENT MENS REA: ANOTHER STAB AT A WORKABLE INTEGRATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULPABILITY INTO CORPORATE CRIMINAL LIABILITY INTRODUCTION “It is a poor legal system indeed which is unable to differentiate between the law breaker and the innocent victim of circumstances so that it must punish both alike.”1 This observation summarizes the pervasive flaw with the present standards of vicarious liability used to impose criminal liability on organizations. As in civil lawsuits, corporate criminal liability at the federal level and in many states is imposed using a strict respondeat superior standard: -

Traditional Academic Calendar Two Semesters, May Term and Summer Session

Traditional Academic Calendar Two Semesters, May Term and Summer Session FALL SEMESTER 2020-21-Revised 2021-22 2022-23 New students arrive August 14 Aug 27 Aug 26 Final fall check-in August 17 Aug 30 Aug 29 Classes begin August 18, 8 a.m.* Aug 31, 8:00 a.m.* Aug 30, 8:00 a.m.* Drop-Add period ends, 5 p.m. August 25, 5:00 Sept 7, 5:00 p.m. Sept 6, 5:00 p.m. p.m. Homecoming Oct. 2-4 Oct 1-3 Oct 7-9 Mid-term break Study days: Sept Oct 18-22 Oct 17-21 30 & Oct 13 Last day to withdraw with a “W” Oct. 16 Nov 5 Nov 4 Academic advising period Oct. 15-30 Nov 4-19 Nov 3-18 Thanksgiving break Nov 25-26 Nov 24-25 Last Day of Classes Nov. 19 Dec 10 Dec 9 Reading Day None Dec 13 Dec 12 Final Exams Nov. 20-24 Dec 14-16 Dec 13-15 Grades Due Dec. 2 Dec 21 Dec 20 SPRING SEMESTER 2020-21 Revised 2021-22 2022-23 New student day, final Mon, Jan. 11 Jan 11 Jan 10 registration Classes begin, 8 a.m. Tues, Jan. 12 ** Jan 12 Jan 11 Drop-Add period ends, 5 p.m. Tues, Jan 19, 5:00 Jan 18, 5:00 p.m. Jan 17, 5:00 p.m. Martin Luther King Jr. Study Day (evening classes in session) Jan. 18 Jan 17 Jan 16 Mid-term break ***Study days: Feb 28-March 4 Feb 27-March 3 Feb 3 & 23, Mar 16, Apr 2 & 19 Last day to withdraw with a “W” March 12 March 18 March 17 Academic Advising period March 11-26 Mar 17-Apr 1 March 16-31 Good Friday Holiday April 2 April 15 April 7 Last Day of Classes April 16 April 21 April 21 Reading Day April 19 April 25 April 24 Final Exams April 20-22 Apr 26-28 April 25-27 Baccalaureate Service, 11 a.m. -

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

COVID-19 Update for the August 10, 2021 Board of Supervisors Meeting

Date: August 5, 2021 To: The Honorable Chair and Members From: C.H. Huckelberry Pima County Board of Supervisors County Administrator Re: COVID-19 Update for the August 10, 2021 Board of Supervisors Meeting Pandemic Update After a nadir at the end of May which experienced 244 cases that week, the number of cases has risen during each week in July, and is now estimated at 1,098 cases the last week of July. During that time COVID-19 test positivity has increased from 3 percent the last week of May, to 9 percent last week. The increase in cases has occurred almost exclusively among the unvaccinated portions of our population, impacting predominantly the 15 to 19 and 20 to 40 age groups. Variants of concern, including the Alpha and Delta variants, have been detected among 68 percent of the specimens forwarded to the State for variant analysis as part of our limited surveillance. Among these Alpha and Delta variants continues to predominate and is identified in 59 percent of positive tests that are sequenced. Notably, the Delta variant in Pima County has increased every week since mid-June. National surveillance has identified Delta as the predominant variant in the U.S., and that is likely to happen here locally in the very near future. We have become aware that the State Health Department will be unveiling a landing page reporting on variant distribution and we will transmit that information to the Board as soon as it its available. COVID-19 infections occurring among fully vaccinated individuals (breakthrough infections) remain a small but concerning fraction of the cases occurring in Pima County. -

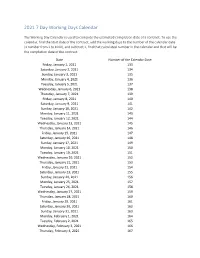

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

Crimes Against Property

9 CRIMES AGAINST PROPERTY Is Alvarez guilty of false pretenses as a Learning Objectives result of his false claim of having received the Congressional Medal of 1. Know the elements of larceny. Honor? 2. Understand embezzlement and the difference between larceny and embezzlement. Xavier Alvarez won a seat on the Three Valley Water Dis- trict Board of Directors in 2007. On July 23, 2007, at 3. State the elements of false pretenses and the a joint meeting with a neighboring water district board, distinction between false pretenses and lar- newly seated Director Alvarez arose and introduced him- ceny by trick. self, stating “I’m a retired marine of 25 years. I retired 4. Explain the purpose of theft statutes. in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Con- gressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by 5. List the elements of receiving stolen property the same guy. I’m still around.” Alvarez has never been and the purpose of making it a crime to receive awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, nor has he stolen property. spent a single day as a marine or in the service of any 6. Define forgery and uttering. other branch of the United States armed forces. The summer before his election to the water district board, 7. Know the elements of robbery and the differ- a woman informed the FBI about Alvarez’s propensity for ence between robbery and larceny. making false claims about his military past. Alvarez told her that he won the Medal of Honor for rescuing the Amer- 8. -

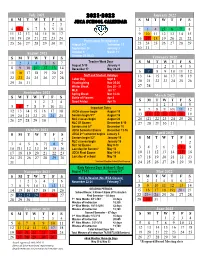

2021-2022 JECA School Calendar

July 2021 2021-2022 January 2022 S M T W T F S JECA School Calendar S M T W T F S 1 2 3 1 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 [5 6 7 8 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Professional Development 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 August 2-4 November 12 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 September 24 January 3 30 31 August 2021 October 8 March 11 October 29 (NLC) February 2022 S M T W T F S Teacher Work Days 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 S M T W T F S August 5-10 January 4 1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 [11 12 13 14 December 17 May 20-24 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Staff and Student Holidays 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Labor Day Sept 6 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 29 30 31 Thanksgiving Nov 25-26 Winter Break Dec 20 - 31 27 28 MLK Jan 17 September 2021 Spring Break Mar 14-18 March 2022 S M T W T F S Battle of Flowers Apr 8 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 Good Friday Apr 15 1 2 3 4 5 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Important Dates 6 7 8 9 10] 11 12 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 JECA classes begin August 10 Seniors begin S1* August 16 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 NLC classes begin August 23 20 [21 22 23 24 25 26 26 27 28 29 30 NLC S1 Exams December 6-10 27 28 29 30 31 Seniors end S1* December 10 October 2021 JECA Semester Exams December 13-16 nd April 2022 S M T W T F S JECA 2 semester begins January 5 Seniors begin S2* January 10 S M T W T F S 1 2 NLC classes begin January 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7] 8 9 NLC S2 Exams May 9-13 10 [11 12 13 14 15 16 Last day for Seniors* May 13 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 JECA Final Exams May 16-19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Last day of school May -

2021-2022 Academic Calendar

PRESCOTT UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT SCHOOL CALENDAR FOR 2021-2022 2021 July August September S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 October November December S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 31 2022 January February March S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 27 28 29 30 31 30 31 April May June S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 Pay Days Work Day/No Students End of Grading Period Employees/Students Off All Offices (12-month employees work) Closed due to four- First/Last Day of School Half -Day PHS Only All Employees/Students Off Half-Day for Students day work week. -

CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY: the STATE of MIND CRIME-INTENT, PROVING INTENT, and ANTI-FEDERAL Intentt

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Criminal Conspiracy: The tS ate of Mind Crime - Intent, Proving Intent, Anti-Federal Intent Paul Marcus William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Marcus, Paul, "Criminal Conspiracy: The tS ate of Mind Crime - Intent, Proving Intent, Anti-Federal Intent" (1976). Faculty Publications. 557. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/557 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY: THE STATE OF MIND CRIME-INTENT, PROVING INTENT, AND ANTI-FEDERAL INTENTt Paul Marcus* I. INTRODUCTION The crime of conspiracy, unlike other substantive or inchoate crimes, deals almost exclusively with the state of mind of the defendant. Although a person may simply contemplate committing a crime without violating the law, the contemplation becomes unlawful if the same criminal thought is incorporated in an agreement. The state of mind element of conspiracy, however, is not concerned entirely with this agreement. As Dean Harno properly remarked 35 years ago, "The conspiracy consists not merely in the agreement of two or more but in their intention."1 That is, in their agreement the parties not only must understand that they are uniting to commit a crime, but they also must desire to complete that crime as the result of their combination. Criminal conspiracy, therefore, involves two distinct states of mind. The first state of mind prompts the conspirators to reach an agreement; the second relates to the crime that is the object of the agreement. -

Bank Robbery Motion to Dimiss

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND SOUTHERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA * v. * Criminal No. _____________________ * * * * * * * * * * * * DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS COUNT Comes now Mr. _________, by and through his undersigned counsel, James Wyda, Federal Public Defender for the District of Maryland and _______________, Assistant Federal Public Defender, hereby moves this Honorable Court, pursuant to Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 12(b)(3)(B)(v) and (b)(1) to dismiss Count ___ (alleged violation of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)) for failure to state a claim. As will be explained herein, the federal bank robbery offense (Count __) underlying the § 924(c) offense/Count __ categorically fails to qualify as a crime of violence within the meaning of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(3)(A), and the residual clause of § 924(c)(3)(B) is unconstitutionally vague under Johnson v. United States, __ U.S. __, 135 S. Ct. 2551 (2015). Therefore, Count 2 does not state an offense and must be dismissed. INTRODUCTION Count __ of the current superseding indictment currently charges Mr. ____ with ___ a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence in violation of 18 U.S.C. 924(c). Specifically, the Count alleges that the underlying “crime of violence” for the 924(c) is federal bank robbery in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2113(a). However, the Government cannot prove this charge because the offense of federal bank robbery categorically fails to qualify as a “crime of violence.” As explained herein, the Supreme Court’s recent precedent in Johnson renders the Government’s task unachievable. -

Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton Alex Kreit [email protected]

American University Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 3 Article 2 2008 Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton Alex Kreit [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Kreit, Alex. “Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton.” American University Law Review 57, no.3 (February, 2008): 585-639. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vicarious Criminal Liability and the Constitutional Dimensions of Pinkerton Abstract This article considers what limits the constitution places on holding someone criminally liable for another's conduct. While vicarious criminal liability is often criticized, there is no doubt that it is constitutionally permissible as a general matter. Under the long-standing felony murder doctrine, for example, if A and B rob a bank and B shoots and kills a security guard, A can be held criminally liable for the murder. What if, however, A was not involved in the robbery but instead had a completely separate conspiracy with B to distribute cocaine? What relationship, if any, does the constitution require between A's conduct and B's crimes in order to hold A liable for them? It is clear A could not be punished for B's crimes simply because they are friends. -

Conditional Intent and Mens Rea

Legal Theory, 10 (2004), 273–310. Printed in the United States of America Published by Cambridge University Press 0361-6843/04 $12.00+00 CONDITIONAL INTENT AND MENS REA Gideon Yaffe* University of Southern California There are many categories of action to which specific acts belong only if performed with some particular intention. Our commonsense concepts of types of action are sensitive to intent—think of the difference between lying and telling an untruth, for instance—but the law is replete with clear and unambiguous examples. Assault with intent to kill and possession of an illegal drug with intent to distribute are both much more serious crimes than mere assault and mere possession. A person is guilty of a crime of attempt— attempted murder, for instance, or attempted rape—only if that person had the intention to perform a crime. Under the federal carjacking law, an act of hijacking an automobile counts as carjacking only if performed with the intention to kill or inflict serious bodily harm on the driver of the car.1 In all of these cases, the question of whether or not a particular defendant had the precise intention necessary for the crime can make a huge difference, often a difference of years in prison, but sometimes literally a difference of life or death; sometimes whether the crime is one for which the death penalty can be given turns solely on the question of whether or not the actor had the relevant intention. Now, we ordinarily recognize a distinction between a conditional inten- tion to act, which we might express with the words “I intend to A if X,” and an unconditional intention to perform the same action.