Wisdom from on High 1 Kings 2:10-12, 3:3-14 Solomon Was Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship Between Spirituality and Wisdom

DISSERTATION PROTECTIVE FACTORS AGAINST ALCOHOL ABUSE IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: SPIRITUALITY, WISDOM, AND SELF-TRANSCENDENCE Submitted by Sydney E. Felker Department of Psychology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2011 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Kathryn M. Rickard Co-Advisor: Richard M. Suinn Lisa Miller Thao Le Copyright by Sydney E. Felker 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT PROTECTIVE FACTORS AGAINST ALCOHOL ABUSE IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: SPIRITUALITY, WISDOM, AND SELF-TRANSCENDENCE Past research consistently suggests that spirituality is a protective factor against substance abuse in adolescents and adults. Many other personality and environmental factors have been shown to predict alcohol abuse and alcohol-related problems, yet much of the variance in alcohol abuse remains unexplained. Alcohol misuse continues to plague college campuses in the United States and recent attempts to reduce problematic drinking have fallen short. In an effort to further understand the factors contributing to students’ alcohol abuse, this study examines how spirituality, wisdom, and self- transcendence impact the drinking behaviors of college students. Two groups of students were studied: 1. students who were mandated for psychoeducational and clinical intervention as a result of violating the university alcohol policy; 2. a comparison group of students from the general undergraduate population who had never been sanctioned for alcohol misuse on campus. Alcohol use behaviors were assessed through calculating students’ reported typical blood alcohol level and alcohol-related problems. Results showed that wisdom is significantly and negatively related to blood alcohol level and alcohol-related problems for the mandated group but not the comparison group. -

Solomon Reflects on the Meaning of Life

SESSION 11 Solomon Reflects on the Meaning of Life SESSION SUMMARY In this session, we are going to align ourselves with Solomon and ask some of the same questions he asked. As we pose these questions together, we should look for their resolution in the person and work of Jesus Christ. Knowing that God exists, we can experience a life of meaning, justice, and purpose. We also call others to seek answers to their questions by looking to Christ. SCRIPTURE Ecclesiastes 1:1-11; 3:16–4:3; 12:9-14 106 Leader Guide / Session 11 THE POINT Because God exists, life has meaning and purpose. INTRO/STARTER 5-10 MINUTES Option 1 What do you think of when you hear the word vanity? The term vanity can refer to breath, emptiness, something temporary, or meaninglessness. Throughout the Book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon used a from of this word at least 24 times. Solomon used this phrasing to demonstrate the meaninglessness of living life apart from God. The term vanity of vanities is a superlative, emphasizing the emptiness of a Godless life. Without God, life is empty, holds no real meaning, and provides no lasting significance. He showed that only God can add real meaning to life. • Does life seem meaningless to you? Why or why not? Believers do not have to go through life wondering if they have purpose or meaning. God brings purpose and meaning to life. Sometimes that feeling of hopelessness still seeps in. But a vibrant relationship with the Lord enables people to view their lives in a more positive way. -

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS IN THE SOLOMON NARRATIVE OF 1 KINGS 1–11 John A. Davies Summary The narrative in 1 Kings 1–11 makes use of the literary device of sevenfold lists of items and sevenfold recurrences of Hebrew words and phrases. These heptadic patterns may contribute to the cohesion and sense of completeness of both the constituent pericopes and the narrative as a whole, enhancing the readerly experience. They may also serve to reinforce the creational symbolism of the Solomon narrative and in particular that of the description of the temple and its dedication. 1. Introduction One of the features of Hebrew narrative that deserves closer attention is the use (consciously or subconsciously) of numeric patterning at various levels. In narratives, there is, for example, frequently a threefold sequence, the so-called ‘Rule of Three’1 (Samuel’s three divine calls: 1 Samuel 3:8; three pourings of water into Elijah’s altar trench: 1 Kings 18:34; three successive companies of troops sent to Elijah: 2 Kings 1:13), or tens (ten divine speech acts in Genesis 1; ten generations from Adam to Noah, and from Noah to Abram; ten toledot [‘family accounts’] in Genesis). One of the numbers long recognised as holding a particular fascination for the biblical writers (and in this they were not alone in the ancient world) is the number seven. Seven 1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (rev. edn; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968; tr. from Russian, 1928): 74; Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots of Literature: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004): 229-35; Richard D. -

Practical Wisdom

© Michael Lacewing Practical wisdom The syllabus defines practical wisdom as ‘the capacity to make informed, rational judgements without recourse to a formal decision procedure’. Many deontological theories argue that there is no formal decision procedure, and in fact even Kant, who has a formal decision procedure, argues that applying the Categorical Imperative correctly involves ‘judgment’, which cannot be formalized. However, the idea of practical wisdom is today most strongly associated with Aristotle, so we shall focus our discussion on his view of how to make moral decisions. Practical wisdom (Greek phronesis; sometimes translated ‘prudence’), says Aristotle, is ‘a true and reasoned state of capacity to act with regard to the things that are good or bad for man’ Nicomachean Ethics VI.5). So while practical wisdom involves knowledge of what is good or bad, it is not merely theoretical knowledge, but a capacity to act on such knowledge as well. This capacity requires 1. a general conception of what is good or bad, which Aristotle relates to the conditions for human flourishing; 2. the ability to perceive, in light of that general conception, what is required in terms of feeling, choice, and action in a particular situation; 3. the ability to deliberate well; and 4. the ability to act on that deliberation. Aristotle’s theory makes practical wisdom very demanding. The type of insight into the good that is needed and the relation between practical wisdom and virtues of character are both complex. Practical wisdom cannot be taught, but requires experience of life and virtue. Only the person who is good knows what is good, according to Aristotle. -

Bible Chronology of the Old Testament the Following Chronological List Is Adapted from the Chronological Bible

Old Testament Overview The Christian Bible is divided into two parts: the Old Testament and the New Testament. The word “testament” can also be translated as “covenant” or “relationship.” The Old Testament describes God’s covenant of law with the people of Israel. The New Testament describes God’s covenant of grace through Jesus Christ. When we accept Jesus as our Savior and Lord, we enter into a new relationship with God. Christians believe that ALL Scripture is “God-breathed.” God’s Word speaks to our lives, revealing God’s nature. The Lord desires to be in relationship with His people. By studying the Bible, we discover how to enter into right relationship with God. We also learn how Christians are called to live in God’s kingdom. The Old Testament is also called the Hebrew Bible. Jewish theologians use the Hebrew word “Tanakh.” The term describes the three divisions of the Old Testament: the Law (Torah), the Prophets (Nevi’im), and the Writings (Ketuvim). “Tanakh” is composed of the first letters of each section. The Law in Hebrew is “Torah” which literally means “teaching.” In the Greek language, it is known as the Pentateuch. It comprises the first five books of the Old Testament: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. This section contains the stories of Creation, the patriarchs and matriarchs, the exodus from Egypt, and the giving of God’s Law, including the Ten Commandments. The Prophets cover Israel’s history from the time the Jews entered the Promised Land of Israel until the Babylonian captivity of Judah. -

WISDOM (Tlwma) and Pffllosophy (FALSAFA)

WISDOM (tLWMA) AND PfflLOSOPHY (FALSAFA) IN ISLAMIC THOUGHT (as a framework for inquiry) By: Mehmet ONAL This thcsis is submitted ror the Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Wales - Lampeter 1998 b"9tr In this study the following two hypothesisare researched: 1. "WisdotW' is the fundamental aspect of Islamic thought on which Islamic civilisation was established through Islamic law (,Sharfa), theology (Ldi-M), philosophy (falsafq) and mysticism (Surism). 2. "Due to the first hypothesis Islamic philosophy is not only a commentary on the Greek philosophy or a new form of Ncoplatonism but a native Islamic wisdom understandingon the form of theoretical study". The present thesis consists of ten chaptersdealing with the concept of practical wisdom (Pikmq) and theoretical wisdom (philosophy or falsafa). At the end there arc a gcncral conclusion,glossary and bibliography. In the introduction (Chapter One) the definition of wisdom and philosophy is establishedas a conceptualground for the above two hypothesis. In the following chapter (Chapter Two) I focused on the historical background of these two concepts by giving a brief history of ancient wisdom and Greek philosophy as sourcesof Islamic thought. In the following two chapters (Chapter Three and Four) I tried to bring out a possibledefinition of Islamic wisdom in the Qur'5n and Sunna on which Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), theology (A-alim), philosophy (falsafq) and mysticism (Sufism) consistedof. As a result of the above conceptual approaching,I tried to reach a new definition for wisdom (PiLma) as a method that helps in the establishmentof a new Islamic way of life and civilisation for our life. -

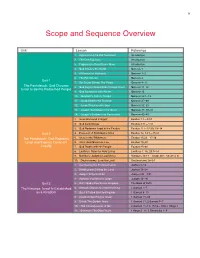

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Othb6313 Hebrew Exegesis: 1 & 2 Kings

OTHB6313 HEBREW EXEGESIS: 1 & 2 KINGS Dr. R. Dennis Cole Fall 2015 Campus Box 62 3 Hours (504)282-4455 x 3248 Email: [email protected] Seminary Mission Statement: The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill The Great Commission and The Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. Course Description: This course combines an overview of 1 & 2 Kings and its place in the Former Prophets with an in-depth analysis of selected portions of the Hebrew text. Primary attention will be given to the grammatical, literary, historical, and theological features of the text. The study will include a discussion of the process leading to hermeneutical goals of teaching and preaching. Student Learning Outcomes: Upon the successful completion of this course the student will have demonstrated a proper knowledge of and an ability to use effectively in study, teaching and preaching: 1. The overall literary structure and content of 1 & 2 Kings. 2. The major theological themes and critical issues in the books. 3. The Hebrew text of 1 & 2 Kings. 4. Hebrew syntax and literary stylistics. NOBTS Core Values Addressed: Doctrinal Integrity: Knowledge and Practice of the Word of God Characteristic Excellence: Pursuit of God’s Revelation with Diligence Spiritual Vitality: Transforming Power of God’s Word Mission Focus: We are here to change the world by fulfilling the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. This is the 2015-16 core value focus. Textbooks: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 1 Kings, Simon DeVries (Word Biblical Commentary) 2 Kings, T.R. -

What Is Philosophy.Pdf

I N T R O D U C T I O N What Is Philosophy? CHAPTER 1 The Task of Philosophy CHAPTER OBJECTIVES Reflection—thinking things over—. [is] the beginning of philosophy.1 In this chapter we will address the following questions: N What Does “Philosophy” Mean? N Why Do We Need Philosophy? N What Are the Traditional Branches of Philosophy? N Is There a Basic Method of Philo- sophical Thinking? N How May Philosophy Be Used? N Is Philosophy of Education Useful? N What Is Happening in Philosophy Today? The Meanings Each of us has a philos- “having” and “doing”—cannot be treated en- ophy, even though we tirely independent of each other, for if we did of Philosophy may not be aware of not have a philosophy in the formal, personal it. We all have some sense, then we could not do a philosophy in the ideas concerning physical objects, our fellow critical, reflective sense. persons, the meaning of life, death, God, right Having a philosophy, however, is not suffi- and wrong, beauty and ugliness, and the like. Of cient for doing philosophy. A genuine philo- course, these ideas are acquired in a variety sophical attitude is searching and critical; it is of ways, and they may be vague and confused. open-minded and tolerant—willing to look at all We are continuously engaged, especially during sides of an issue without prejudice. To philoso- the early years of our lives, in acquiring views phize is not merely to read and know philoso- and attitudes from our family, from friends, and phy; there are skills of argumentation to be mas- from various other individuals and groups. -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

Two Types of Wisdom

Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 2012 Two Types of Wisdom Jason Baehr Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/phil_fac Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Baehr, Jason. “Two Types of Wisdom.” Acta Analytica 27 (2012): 81-97. Print. This Article - pre-print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [This is a penultimate version of the paper. Please cite only the final version, which is forthcoming in Acta Analytica.] TWO TYPES OF WISDOM Jason Baehr Loyola Marymount University In a paper titled “Dare to Be Wise,” Richard Taylor remarks: Students of philosophy learn very early—usually the first day of their first course—that philosophy is the love of wisdom. This is often soon forgotten, however, and there are even men who earn their livelihood at philosophy who have not simply forgotten it, but who seem positively to scorn the idea. A philosopher who … dedicates himself to wisdom is likely to be thought of as one who has missed his calling, who belongs in a pulpit, perhaps, or in some barren retreat for sages, but hardly in the halls of academia. (1968: 615) It is difficult to deny that Taylor is onto something here. Aside from some of the secondary literature in ancient philosophy on phronesis, wisdom receives exceedingly little attention among philosophers today.1 Whatever the explanation of this neglect might be, I think it is largely unwarranted, and indeed that now is an especially appropriate time for epistemologists and ethicists to give more focused attention to wisdom. -

WHY BARZILLAI of GILEAD (1 KINGS 2:7)? NARRATIVE ART and the HERMENEUTICS of SUSPICION in 1 KINGS 1-2 Iain W

Tyndale Bulletin 46.1 (1995) 103-116. WHY BARZILLAI OF GILEAD (1 KINGS 2:7)? NARRATIVE ART AND THE HERMENEUTICS OF SUSPICION IN 1 KINGS 1-2 Iain W. Provan Summary Even if one remains uneasy about the precise direction in which much recent scholarship on biblical narrative has been moving, it is the case that much can be learned from the kind of approaches which have been developed. This paper argues, for example, that the author of 1 Kings 1-2 invites the reader to employ a ‘hermeneutic of suspicion’ in relation to his story by the artful way in which he tells it; and that the employment of such a hermeneutic enables a deeper grasp of what the story is about than would otherwise be possible. I. Introduction These are interesting times for those who are concerned with the interpretation of biblical texts, particularly Hebrew narrative texts. Old certainties are under attack. New revolutionaries clamber over the barricades, pronouncing those only recently considered (and considering themselves) as radicals to be, in fact, boringly conservative and quite passé. It seems just a blink of the eye ago, for example, that the average commentator on Kings thought it an important part of his task to tell his readers quite a bit about the sources from which the book might have been constructed and the editors who might successively have worked upon it. Of the existence of such sources and editors there was really no doubt, even if there was much disagreement about the details. It was simply accepted that there was a greater or lesser degree of incoherence in the text—inconsistencies, repetitions, variations in style and language, and so on—features unexpected, it 104 TYNDALE BULLETIN 46.1 (1995) was said, in the work of a single author.