Correnti Della Storia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I MIEI 40 ANNI Di Progettazione Alla Fiat I Miei 40 Anni Di Progettazione Alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA

DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat Editing e apparati a cura di: Angelo Tito Anselmi Progettazione grafica e impaginazione: Fregi e Majuscole, Torino Due precedenti edizioni di questo volume, I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat e Progetti alla Fiat prima del computer, sono state pubblicate da Automobilia rispettivamente nel 1979 e nel 1988. Per volere della signora Mariella Zanon di Valgiurata, figlia di Dante Giacosa, questa pubblicazione ricalca fedelmente la prima edizione del 1979, anche per quanto riguarda le biografie dei protagonisti di questa storia (in cui l’unico aggiornamento è quello fornito tra parentesi quadre con la data della scomparsa laddove avve- nuta dopo il 1979). © Mariella Giacosa Zanon di Valgiurata, 1979 Ristampato nell’anno 2014 a cura di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. Logo di prima copertina: courtesy di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. … ”Noi siamo ciò di cui ci inebriamo” dice Jerry Rubin in Do it! “In ogni caso nulla ci fa più felici che parlare di noi stessi, in bene o in male. La nostra esperienza, la nostra memoria è divenuta fonte di estasi. Ed eccomi qua, io pure” Saul Bellow, Gerusalemme andata e ritorno Desidero esprimere la mia gratitudine alle persone che mi hanno incoraggiato a scrivere questo libro della mia vita di lavoro e a quelle che con il loro aiuto ne hanno reso possibile la pubblicazione. Per la sua previdente iniziativa di prender nota di incontri e fatti significativi e conservare documenti, Wanda Vigliano Mundula che mi fu vicina come segretaria dal 1946 al 1975. -

Designed for Speed : Three Automobiles by Ferrari

Designed for speed : three automobiles by Ferrari Date 1993 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/411 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art * - . i . ' ' y ' . Designed for Speed: Three Automobiles by Ferrari k \ ' . r- ; / THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK The nearer the automobile approaches its utilitarian ends, the more beautiful it becomes. That is, when the vertical lines (which contrary to its purpose) dominated at its debut, it was ugly, and people kept buying horses. Cars were known as "horseless carriages." The necessity of speed lowered and elongated the car so that the horizontal lines, balanced by the curves, dominated: it became a perfect whole, logically organized for its purpose, and it was beautiful. —Fernand Leger "Aesthetics of the Machine: The Manufactured Object, The Artisan, and the Artist," 1924 M Migh-performance sports and racing cars represent some of the ultimate achievements of one of the world's largest industries. Few objects inspire such longing and acute fascination. As the French critic and theorist Roland Barthes observed, "I think that cars today are almost the exact equiv alent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object." Unlike most machines, which often seem to have an antagonistic relationship with people, these are intentionally designed for improved handling, and the refinement of the association between man and machine. -

Gpnuvolari-Trofeolotus-1-10-39895

La scomparsa di Tazio Nuvolari, avvenuta l'11 agosto 1953, destò grande sensazione in tutto il mondo, in particolare, commosse gli uomini della Mille Miglia, Renzo Castagneto, Aymo Maggi e Giovanni Canestrini, i tre che con Franco Mazzotti, scomparso durante la II Guerra Mondiale, avevano ideato e realizzato la "corsa più bella del mondo". Castagneto, il deus ex machina della Mille Miglia, ed i suoi amici erano autenticamente legati al pilota mantovano, non solo per l'affetto e la stima per l'uomo e l'ammirazione che provavano per il grande campione, ma anche per i sentimenti di riconoscenza che gli attribuivano, per essere stato tra coloro che, con le proprie gesta, avevano maggiormente contribuito all'inarrestabile crescita della loro creatura. Per onorarne la memoria, gli organizzatori della Mille Miglia modificarono il percorso tradizionale così da transitare per Mantova. Da allora, venne istituito il GRAN PREMIO NUVOLARI, da destinare al pilota più veloce e quindi da disputarsi sui lunghi rettilinei che percorrono la pianura Padana, partendo da Cremona e transitando per Mantova, fino al traguardo di Brescia. Oltre alle quattro edizioni storiche svoltesi dal 1954 al 1957 e volute dagli organizzatori della 1000 Miglia, ad oggi si sono disputate 30 rievocazioni del GRAN PREMIO NUVOLARI, la formula, regolarità internazionale riservata ad auto storiche. Dal 1991, i soci fondatori di Mantova Corse, Luca Bergamaschi, Marco Marani, Fabio Novelli e Claudio Rossi, continuano nella medesima opera tramandata dai leggendari fondatori della 1000 Miglia. Il fine, lo stesso: consentire ai piloti delle nuove generazioni di cimentarsi sulle vetture che scrissero la storia di quei giorni, rendendo omaggio al più grande, al più ardimentoso al più audace dei loro predecessori: il leggendario Tazio Nuvolari. -

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

Pierugo Gobbato

Testimonianze su Ugo Gobbato Pierugo Gobbato “ apà (Ugo) e mamma (Dianella Marsiaj) Lingotto, dove sarebbero state trasferite negli Psi erano sposati a Milano nel 1916 e lì anni successivi tutte le lavorazioni della fab- era nata, nel febbraio 1917 la prima figlia, briche iniziali Fiat in corso Dante. Annafranca (Bebè). Papà era in guerra (sottotenente del genio La Fiat era in fase di espansione e cercava minatori) ed era stato sul Carso, Oslavia e tecnici per guidare la nuova dimensione. Podgora, in trincea. Cossalter, ancora militare presso la Fiat, se- Con lo svilupparsi dell’aeronautica, era stato gnalò al Cav. Agnelli, maggiore azionista poi assegnato, come ufficiale tecnico, in vari della società, il nominativo di papà, esal- campi dell’aviazione, dove aveva stretto tandone le doti di grande tecnico ed ottimo amicizia con i piloti della squadriglia Baracca organizzatore. Per questo fu assunto, e così (Meo Costantini, che poi venne a lavorare con tutta la famiglia ci trasferimmo a Torino, all’Alfa Romeo, Ranza, Masporone ecc.). verso la fine del 1918 e prendemmo alloggio Nelle varie peregrinazioni che il suo ruolo in corso Dante (al numero civico 40, divenuto richiedeva, si era trovato anche a passare poi con l’espandersi della città 118). Oggi la all’aeroporto di Taliedo (Milano) dove casa è assolutamente identica ad allora e noi aveva conosciuto l’Ing. Caproni, costruttore occupavamo tutto l’ultimo piano, dai balconi di aerei militari. della quale si vedevano tutte le officine Fiat Nel giugno del 1918, papà era stato trasferito di corso Dante. in turno di riposo, all’aeroporto di Firenze, Ricordo che da quel balcone assistetti al lancio per assistenza ad un gruppo di lavoro che di manifestini da un aeroplano (pilotato da un assemblava aerei da caccia. -

Story of the Alfa Romeo Factory and Plants : Part 1 the Early Portello

Story of the Alfa Romeo factory and plants: Part 1 The early Portello Factory Patrick Italiano Special thanks go to Karl Schnelle, Indianapolis, USA, for his patient proofreading and editing of the English version of this text Over the last few years, we have had to deal with large changes in Alfa Romeo-related places and buildings, as we witnessed the destruction of the old Portello factory, step by step in the late 80s, and also the de-commissioning of the much more modern Arese plant. Sad tales and silly pictures of places and people once full of pride in manufacturing the most spirited cars in the world. As reported by historians, it has long been – and still is for few – a source of pride to belong to this “workers aristocracy” at A.L.F.A.. Places recently destroyed to make place for concrete buildings now containing commercial centres or anonymous offices, places where our beloved cars were once designed, developed and built. It’s often a mix of curiosity and thrill to have the chance to look behind the scenes and see into the sanctuary. Back in 1987, when the first part of Portello was being torn down, Ben Hendricks took us on a visit to the Portello plant in Het Klaverblaadje #40. That was, as Jos Hugense coined the title 15 years later, the “beginning of the end”. Today, one can see Alfas running on the Fiat assembly lines along with Fiat Stilos and at best Lancia Thesis. These Fiat plants are no longer the places where distinguished and passionate brains try to anticipate technical trends five years into the future, thus ensuring that the new generation of Alfas keep such high company standards, as Ing. -

50 YEARS AGO at SEBRING, CALIFORNIA PRIVATEERS USED 550-0070 to TAKE on BARON HUSCHKE VON Hansteinrs FAC- TORY PORSCHES-AND NEAR

50 YEARS AGO AT SEBRING, CALIFORNIA PRIVATEERS USED 550-0070 TO TAKE ON BARON HUSCHKE VON HANSTEINrS FAC- TORY PORSCHES-AND NEARLY BEATTHEM SrORYBYWALEDGAR PHOTOSBYJlAllSrrZANDCOURTESYOF THE EDOARrn~BRCHM L )hn Edgar had an idea. His and film John von Newnann race me. It Edwsi&a was niow a r&ng program. egendary MG "88" Special was an impressive performance. Only Chassis number 552-00M arrived in ~OftetlCaniedhotshoeJaick Pete Lovely3 hornsbuilt "PorscheWagen" $mfor Jack McAfee to debut the Edgar- dcAfee to American road- came closs to it in class. Edgar wibessxl entered Spyder at Sanfa Barbara's 1955 racing victorias and, by 1955, the 550's speed winon MmialDay at Labor Day sportscar races. Unfamiliar Edgar saw no reason why Santa Barbara and at Torrey Pins tn July. 4th the SwakMBWlfty, Mfee managed JN1CAtest wldnY get Weagain in the la?- He studied his footage again and agaln. rw better than fourth. But the car felt right, & and gm-dest Under 15KI-c~mmhins. Won over by ttre 550's superior handling, e~enin the Elfip d a man as camparaWty That car w&s Porsche's new 550 Spyder. he hesitated no further and ordered one large as McAfee, so the driver-engineer In April of 1%5, Edgar had gone. to thrwgh John rn Neurmnn's Cornpew began ta ready #0070 for a Torrey Pines Mintw Fdd outsi& Bakersfield to watch Mason Vm Street in Hd . John sk-hr endurn in October. On September 30, movie idol James Dean was killed in his own 550, bringing national notice to Porsche's new-to- America 550 Spyder. -

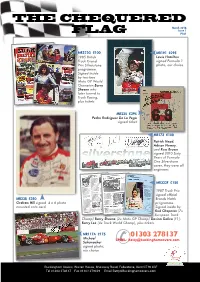

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic. -

20 7584 7403 E-Mail [email protected] 1958 Brm Type 25

14 QUEENS GATE PLACE MEWS, LONDON, SW7 5BQ PHONE +44 (0)20 7584 3503 FAX +44 (0)20 7584 7403 E-MAIL [email protected] 1958 BRM TYPE 25 Chassis Number: 258 Described by Sir Stirling Moss as the ‘best-handling and most competitive front-engined Grand Prix car that I ever had the privilege of driving’, the BRM P25 nally gave the British Formula One cognoscenti a rst glimpse of British single seater victory with this very car. The fact that 258 remains at all as the sole surviving example of a P25 is something to be celebrated indeed. Like the ten other factory team cars that were to be dismantled to free up components for the new rear-engined Project 48s in the winter of 1959, 258 was only saved thanks to a directive from BRM head oce in Staordshire on the express wishes of long term patron and Chairman, Sir Alfred Owen who ordered, ‘ensure that you save the Dutch Grand Prix winner’. Founded in 1945, as an all-British industrial cooperative aimed at achieving global recognition through success in grand prix racing, BRM (British Racing Motors) unleashed its rst Project 15 cars in 1949. Although the company struggled with production and development issues, the BRMs showed huge potential and power, embarrassing the competition on occasion. The project was sold in 1952, when the technical regulations for the World Championship changed. Requiring a new 2.5 litre unsupercharged power unit, BRM - now owned by the Owen Organisation -developed a very simple, light, ingenious and potent 4-cylinder engine known as Project 25. -

Episodio 1 AR

Contact: Miguel Ceballos FCA México: ‘Historias de Alfa Romeo’ Episodio Uno: conducción a bordo del 24 HP La historia comenzó el 24 de junio de 1910, con la fundación de la A.L.F.A. (Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili) Los 24 HP tenían un motor monobloque de 4 cilindros, 4 litros de desplazamiento y 42 caballos de fuerza El 40/60 HP nace en 1913 y fue capaz de alcanzar 139 km/h Enzo Ferrari tuvo una fuerte vinculación con Alfa Romeo en el deporte motor April 20, 2020, Ciudad de México - Historias y personajes de principios del siglo XX, centrados en el primer coche de la firma italiana: un elegante ‘cohete’ capaz de alcanzar 100 km/h. El francés de Nápoles Oficialmente nuestra historia comenzó el 24 de junio de 1910, con la fundación de la A.L.F.A. (Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili). Pero vamos a empezar unos años antes, con un personaje colorido: un francés con un bigote de manillar y un instinto sobresaliente para los negocios. Pierre Alexandre Darracq comenzó su carrera dirigiendo una fábrica de bicicletas en Burdeos, antes de enamorarse de los automóviles. Así, comenzó a producir automóviles en Francia y hacer un éxito de la misma. Luego decidió exportar la apertura de sucursales en Londres y luego Italia. En Italia comenzó sus operaciones, en abril de 1906. Pero Nápoles estaba muy lejos de Francia y el viaje era complejo y costoso. Así, en diciembre había transferido la producción a Milán, en el número 95 en el distrito de Portello. Pero junto con las dificultades logísticas se dio cuenta de que también había problemas de mercado. -

Latest Paintings

ULI EHRET WATERCOLOUR PAINTINGS Latest Paintings& BEST OF 1998 - 2015 #4 Auto Union Bergrennwagen - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #200 Bernd Rosemeyer „Auto Union 16 Cylinder“ - On canvas: 120 x 160 cm, 100 x 140 cm, 70 x 100 cm, 50 x 70 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #468 Rudolf Carraciola / Mercedes W154 - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #52 Hermann Lang „Mercedes Silberpfeil“ #83 Bernd Rosemeyer „Weltrekordfahrt 1936“ - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 30 x 90 cm - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 40 x 80 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #291 Richard Seaman „Donington GP 1937“ - On canvas: 180 x 100 cm, 70 x 150 cm, 50 x 100 cm, 40 x 80 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #88 Stirling Moss „Monza Grand Prix 1955“ - On canvas: 120 x 160 cm, 180 x 100 cm, 80 x 150 cm, 60 x 100 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #277 Jean Pierre Wimille „Talbot Lago T26“ - On canvas: 160 x 120 cm, 150 x 100 cm, 120 x 70 cm, 60 x 40 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm #469 Tazio Nuvolari / Auto Union D-Type / Coppa Acerbo 1938 - On canvas: 180 x 120 cm, 160 x 90 cm, 140 x 70 cm, 90 x 50 cm, 50 x 30 cm - Framed prints: 50 x 60 cm, 40 x 50 cm, 25 x 30 cm - Original: framed 50 x 70 cm, 1.290 Euros original