Information 126

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideal Homes? Social Change and Domestic Life

IDEAL HOMES? Until now, the ‘home’ as a space within which domestic lives are lived out has been largely ignored by sociologists. Yet the ‘home’ as idea, place and object consumes a large proportion of individuals’ incomes, and occupies their dreams and their leisure time while the absence of a physical home presents a major threat to both society and the homeless themselves. This edited collection provides for the first time an analysis of the space of the ‘home’ and the experiences of home life by writers from a wide range of disciplines, including sociology, criminology, psychology, social policy and anthropology. It covers a range of subjects, including gender roles, different generations’ relationships to home, the changing nature of the family, transition, risk and alternative visions of home. Ideal Homes? provides a fascinating analysis which reveals how both popular images and experiences of home life can produce vital clues as to how society’s members produce and respond to social change. Tony Chapman is Head of Sociology at the University of Teesside. Jenny Hockey is Senior Lecturer in the School of Comparative and Applied Social Sciences, University of Hull. IDEAL HOMES? Social change and domestic life Edited by Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. © 1999 Selection and editorial matter Tony Chapman and Jenny Hockey; individual chapters, the contributors All rights reserved. -

Heritage Tourism and the Built Environment

H E RI T A G E T O URISM A ND T H E BUI L T E N V IR O N M E N T By SUR A I Y A T I R A H M A N A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences (Centre for Urban and Regional Studies) University of Birmingham MARCH 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. A BST R A C T The aims of this research are to examine and explore perceptions of the built environmental impacts of heritage tourism in urban settlements; to explore the practice of heritage tourism management; and to examine the consequences of both for the sustainability of the heritage environment. The literature review explores the concepts of heritage management, the heritage production model, the tourist-historic city, and sustainability and the impact of tourism on the built environment. A theoretical framework is developed, through an examination of literature on environmental impacts, carrying capacity, sustainability, and heritage management; and a research framework is devised for investigating the built environmental impacts of heritage tourism in urban settlements, based around five objectives, or questions. -

Norfolk & Suffolk Brecks

NORFOLK & SUFFOLK BRECKS Landscape Character Assessment Page 51 Conifer plantations sliced with rides. An abrupt, changing landscape of dense blocks and sky. Page 34 The Brecks Arable Heathland Mosaic is at the core of the Brecks distinctive landscape. Page 108 Secret river valleys thread through the mosaic of heaths, plantations and farmland. BRECKS LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 04 Introduction Page 128 Local landscapes Context Introduction to the case studies Objectives Status Foulden Structure of the report Brettenham Brandon Page 07 Contrasting acidic and calcareous soils are Page 07 Evolution of the Mildenhall juxtaposed on the underlying Lackford landscape chalk Physical influences Human influences Page 146 The Brecks in literature Biodiversity Article reproduced by kind permission of Page 30 Landscape character the Breckland Society Landscape character overview Page 30 The Brecks Arable Structure of the landscape Heathland Mosaic is at the Annexes character assessment core of the Brecks identity Landscape type mapping at 1:25,000 Brecks Arable Heathland Mosaic Note this is provided as a separate Brecks Plantations document Low Chalk Farmland Rolling Clay Farmland Plateau Estate Farmland Settled Fen River Valleys Page 139 Brettenham’s Chalk River Valleys landscape today, explained through illustrations depicting its history 03 BREAKING NEW GROUND INTRODUCTION Introduction Context Sets the scene Purpose and timing of the study How the study should be used Status and strategic fit with other documents Structure of the report BRECKS LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT INTRODUCTION Introduction Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Context Study Area (NCA 85) Study Area Buffer This landscape character assessment (LCA) County Boundary Castle Acre focuses on the Brecks, a unique landscape of District Boundary heaths, conifer plantations and farmland on part Main Road of the chalk plateau in south-west Norfolk and Railway north-west Suffolk. -

Political Elites and Community Relations in Elizabethan Devon, 1588-1603

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library Networks, News and Communication: Political Elites and Community Relations in Elizabethan Devon, 1588-1603 by Ian David Cooper A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Performing Arts Faculty of Arts In collaboration with Devon Record Office September 2012 In loving memory of my grandfathers, Eric George Wright and Ronald Henry George Cooper, and my godfather, David Michael Jefferies ii Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. iii Abstract Ian David Cooper ‘Networks, News and Communication: Political Elites and Community Relations in Elizabethan Devon, 1588-1603’ Focusing on the ‘second reign’ of Queen Elizabeth I (1588-1603), this thesis constitutes the first significant socio-political examination of Elizabethan Devon – a geographically peripheral county, yet strategically central in matters pertaining to national defence and security. A complex web of personal associations and informal alliances underpinned politics and governance in Tudor England; but whereas a great deal is now understood about relations between both the political elite and the organs of government at the centre of affairs, many questions still remain unanswered about how networks of political actors functioned at a provincial and neighbourhood level, and how these networks kept in touch with one another, central government and the court. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1578

1578 1578 At HAMPTON COURT, Middlesex. Jan 1, Wed New Year gifts. Among 201 gifts to the Queen: by Sir Gilbert Dethick, Garter King of Arms: ‘A Book of the States in King William Conqueror’s time’; by William Absolon, Master of the Savoy: ‘A Bible covered with cloth of gold garnished with silver and gilt and two plates with the Queen’s Arms’; by Petruccio Ubaldini: ‘Two pictures, the one of Judith and Holofernes, the other of Jula and Sectra’.NYG [Julia and Emperor Severus]. Jan 1: Henry Lyte dedicated to the Queen: ‘A New Herbal or History of Plants, wherein is contained the whole discourse and perfect description of all sorts of Herbs and Plants: their divers and sundry kinds: their strange Figures, Fashions, and Shapes: their Names, Natures, Operations and Virtues: and that not only of those which are here growing in this our Country of England, but of all others also of sovereign Realms, commonly used in Physick. First set forth in the Dutch or Almain tongue by that learned Dr Rembert Dodoens, Physician to the Emperor..Now first translated out of French into English by Henry Lyte Esquire’. ‘To the most High, Noble, and Renowned Princess, our most dread redoubtful Sovereign Lady Elizabeth...Two things have moved me...to offer the same unto your Majesty’s protection. The one was that most clear, amiable and cheerful countenance towards all learning and virtue, which on every side most brightly from your Royal person appearing, hath so inflamed and encouraged, not only me, to the love and admiration thereof, but all such others also, your Grace’s loyal subjects...that we think no travail too great, whereby we are in hope both to profit our Country, and to please so noble and loving a Princess...The other was that earnest and fervent desire that I have, and a long time have had, to show myself (by yielding some fruit of painful diligence) a thankful subject to so virtuous a Sovereign, and a fruitful member of so good a commonwealth’.. -

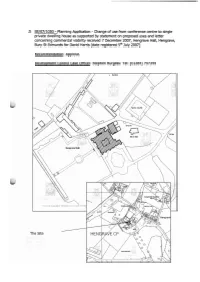

Planning Application

15 SE/07/1050 - Planning Application - Change of use from conference centre to single private dwelling house as supported by statement on proposed uses and letter concerning commercial viability received 7 December 2007, Hengrave Hall, Hengrave, Bury St Edmunds for David Harris (date registered 5th July 2007) Recommendation: Approve. Development Control Case Officer: Stephen Burgess: Tel: (01284) 757345 THE SITE: This application relates to Hengrave Hall, a grade Ilisted building which dates from the mid 16~~century, originally occupied by Sir Thomas Kitson, a merchant. A north-east wing was added in the lgth century, and this was further extended in the 1950's. It is within the Hengrave conservation area but outside of the Housing Settlement Boundary. The Hall is the principal building within a larger estate which comprises several other ancillary buildings, some occupied as dwellings, and an expanse of parkland. Vehicular access to the estate is gained via two accesses from the AllOl, the principal gated access and a secondary access. The estate was occupied as a private residence until 1952 when it became a boarding school and convent. In 1974 planning consent was obtained to change the use to Conference Centre which continued as its use until 2006 when purchased by the current owner. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: N/73/2459 Planning application - Change of use to a conference centre and minor \ alterations to provide additional toilet facilities permission granted February 1974 Pi E/74/1866/P - Planning application - conversion of classroom -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary sources: non-textual material culture consulted Ashmolean Museum, British Archaeology Collections, University of Oxford AN1949.343, Thomas Toft dish (c.1670) Bellevue House, Kingston, Ontario Day & Martin’s blacking bottle, http://www.flickr.com/photos/wiless/5802262137/in/set-72157627086895348 (accessed November 2011) Bodleian Library, John Johnson Collection, University of Oxford Advertising, Boots and Shoes 1 (27c), ‘One cheer more!’ (1817-1837 Advertising, Boots and Shoes 1 (26), ‘Substance versus shadow’ (1817-1837) Advertising, Boots and Shoes 1 (27c), ‘One Cheer More!’ (1817-1837) Advertising, Oil and Candles 1 (31), ‘Untitled advert’ (c.1838-1842 Advertising, Oil and Candles 1 (26a), ’30 Strand’ (.c1830-1835) Advertising, Oil and Candles 1 (27a), ‘The Persian standard; or, the rising sun’ (c.1830s) Advertising, Oil and Candles 1 (28a), ‘A hint!’ (23 December 1831 Advertising, Oil and Candles 1 (28b), ’30 Strand’ (11 November 1831). Advertising posters, Window Bills and Advertisements Folder 4 (2a), ‘Clark’s royal Lemingtonian blacking’ (c.1865-1890) Advertising posters, Window Bills and Advertisements Folder 4 (2b), ‘Kent & Cos. Original & superior royal caoutchouc oil paste blacking’ (c.1860-1890) Advertising posters, Windows Bills and Advertisements Folder 4 (3a), ‘Day and Martin’s real Japan blacking’ (c.1820-1860) Advertising posters, Windows Bills and Advertisements folder 4 (3c), ‘Day and Martin’s real Japan blacking’ (c.1820-1860). Advertising posters, Window Bills and Advertisements Folder 4 (5), ‘Statha[m] and Co. window bill’ (c.1860-1890). Advertising, Window Bills and Advertisements Folder 4 (6), ‘Turner’s Real Japan Blacking’(c.1817 onwards) Labels 1 (3a), ‘B.F. Brown and Co London and Boston’ (November 1893) Labels 1 (3b), ‘B.F. -

Suffolk Record Office New Accessions 1 January 2010-31 December 2010

SUFFOLK RECORD OFFICE NEW ACCESSIONS 1 JANUARY 2010-31 DECEMBER 2010 Bury St Edmunds branch GUILDHALL FEOFFMENT CP SCHOOL, BURY ST EDMUNDS: school records and certificates of Leonard Palfrey 1929-1935 ADB550 RIVERSIDE MIDDLE SCHOOL: admission registers; punishment book; log books 1939-1988; inventory book; volume PTA accounts; scrapbooks and photo albums; loose photos and prospectuses; 3 CD-Roms 1939-1997 ADB738 BRETTENHAM PARISH COUNCIL: planning items; internal/external audit papers; minutes; account ledgers 1946-2000 EG551 SUDBURY TOWN COUNCIL: minutes; film reels and photographs c 1957-2006 EG574 STOKE BY NAYLAND PARISH COUNCIL: minutes; receipts and payments 1952-1999 EG584 BURES ST MARY PARISH COUNCIL: minutes 1935-2008; title deeds and abstract of title relating to recreation ground 1920-2008 EG707 FELSHAM PARISH COUNCIL: minutes 1894-1934; receipts and payments (inc overseers) 1848-1958; parish council elections papers; order for contribution and general cash receipt books 1895-1958; accounts 1930s; treasurer's book 1895-1940; correspondence re water and pumps and Felsham charity c1848-c1958: EG718 MINUTE BOOK OF LAYHAM PLAYGROUP: minutes 1975-2000 EG722 BILDESTON PARISH: Wattisham and Bildeston Parish Chest, documents 20th cent FB79 WHITING STREET UNITED REFORMED CHURCH, BURY ST EDMUNDS: minutes of church, elders' and electors' meetings; visitor's book; photo of members and adherents (with names); photos of ministers; newscutting re welcoming of the church's first woman minister (Jean McCallum); Free Church Council programme -

MEMO Randal Upward Flow in the Surcharged Vessel

TM r aY14, tWS] ~~~~~~~MEMORANDA.L B[UTaE J°=MA 1-33I33 chloride of mercury solution (i in 2,000). The highest points through the aperture in the vaginal septum with the finger at the same of the iliac crests being determined, an imaginary transverse time in the rectum, the point of the sound can be felt free in the upper line was drawn between these points; the left index finger portion of the vaginal canal. was placed upon the point where this imaginary line crowed There was no history or sign of any inflammatory trouble the spine, this point coinciding with the tip of the spinous that might produce cicatricial atresia, and the condition gave process of one of the lumbar vertebrae. A hollow needle, rise to no specific symptoms, its discovery being quite acci- 31 in. long, held in the right hand, was made to pierce the dental. stin 1 in. to the right of the point held by the operator's left Matlock. GEORGE C. R. HARBINSON, M.B., B.Ch. index finger, and was then pushed onwards, being directed slightly upwards and towards the middle line, so as to pass THE ETIOLOGY OF VARICOCELE. beneath the lower edge of the vertebral lamina, and so enter I HAVE a case of ordinary varicocele (left) said to have been the subarachnoid space. caused by a strain. The lad (aged I7) was lifting a heavy Such is the history of these two cases, and the successful trough with his hands behind him, and he says he felt a issue of the second case, which seemed quite hopeless, gives sudden pain in the left groin and found his scrotum swollen. -

Memorials of Old Suffolk

I \AEMORIALS OF OLD SUFFOLK ISI yiu^ ^ /'^r^ /^ , Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldsuOOreds MEMORIALS OF OLD SUFFOLK EDITED BY VINCENT B. REDSTONE. F.R.HiST.S. (Alexander Medallitt o( the Royal Hul. inK^ 1901.) At'THOB or " Sacia/ L(/* I'm Englmnd during th* Wmrt »f tk* R»ut,- " Th* Gildt »nd CkMHtrUs 0/ Suffolk,' " CiUendar 0/ Bury Wills, iJS5-'535." " Suffolk Shi^Monty, 1639-^," ttc. With many Illustrations ^ i^0-^S is. LONDON BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.G. AND DERBY 1908 {All Kifkts Rtterifed] DEDICATED TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE Sir William Brampton Gurdon K.C.M.G., M.P., L.L. PREFACE SUFFOLK has not yet found an historian. Gage published the only complete history of a Sufifolk Hundred; Suckling's useful volumes lack completeness. There are several manuscript collections towards a History of Suffolk—the labours of Davy, Jermyn, and others. Local historians find these compilations extremely useful ; and, therefore, owing to the mass of material which they contain, all other sources of information are neglected. The Records of Suffolk, by Dr. W. A. Copinger shews what remains to be done. The papers of this volume of the Memorial Series have been selected with the special purpose of bringing to public notice the many deeply interesting memorials of the past which exist throughout the county; and, further, they are published with the view of placing before the notice of local writers the results of original research. For over six hundred years Suffolk stood second only to Middlesex in importance ; it was populous, it abounded in industries and manufactures, and was the home of great statesmen. -

1 Archaeology & Architecture Group

ARCHAEOLOGY & ARCHITECTURE GROUP KEYWORTH AND DISTRICT NEWSLETTER 42 JANUARY 2018 PROPOSED U3A A&A Group PROGRAMME 2018 We meet on the third Thursday in the month from 2.00pm in Keyworth Methodist Church, except August, unless out on a pre- arranged visit. There is a £2.00 charge to cover rental, refreshments and resources. Thursday 18th January: 2pm DVD afternoon, KMC: SIX ENGLISH TOWNS (JKB) in Keyworth Methodist Church “Six English Towns” a potted history and architectural study of English towns with character: Chichester (West Sussex); Richmond (Yorkshire); Tewkesbury (Gloucestershire); Stamford (Lincolnshire); Totnes (Devon); Ludlow (Shropshire). If you have any related material – pictures, stories, brochures, experiences – please bring them along. Details of visits: Bridget Bagshaw and Lesley Coote to inform us of arrangements for February and March visits: Thursday 15th February: visit PUGIN’S CATHEDRAL, Derby Road, Nottm (Bridget Bagshaw) Public transport. Many thanks to Bridget Bagshaw for offering to arrange this visit A guided tour of the Catholic Cathedral, Derby Road and Mary Potter Heritage Centre, Regent Street. CONSERVATION AREA ADVISORY GROUP (CAAG) and KEYWORTH & DISTRICT LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY (K&DLHS) You might also be interested in Keyworth Conservation Area Census events: There are 2 each year in the Centenary Lounge; the next will be “Farms, Barns and Rural Buildings” 11am – 4pm on Saturday, 17th February 2018 Keyworth & District Local History Society (KDLHS) Bookstall will offer publications & greetings cards. We invite people to attend with material to be displayed and can scan, save to disc for both you and the archive, and return originals safely. [The November event will be “Commemorating Conflict” on Saturday 17th November, the week after the Centenary of the Armistice]. -

The Family of Dacre. 1

THE FAMILY OF DACRE. NOTE-The R.ererence Mark= signifies married; S,P, signifies sine prole (without Issue) Humphrey Dacre of Holbyche, Lincolnsbyre Anne daughter of Bardolph Richard Dacre = daughter of ............ Beaufort William Dacre daughter of .....•...... Grey of Codnor Thomas De.ere = doughter of. ..... Mowbrey I Humfrey De.ere dougbter of ............ Haryngton Thomas Dacre doughter of ............ Marley Ranulff De.cry doughter of Roos of Kendal --VAUX, Lord of Gylsland daughter and heyr of Huge Morgle William Dacre Dyed 1258 Anne daughter of Derwentwater. Moulton Lord of Gylsland Mawde, daughter and heyr. Randolph Dacre, 1st Lord of Gilisland in the 15 yere of King Henry III. Dyed 1286. Mawde daughter and heyr of Moulton of Gylisland. Thomas 2nd Lord Dacre of Gilisland. Died 1361 Kateren, doughter of Luci Thomas Lord Dacre (presumably, died Elisabeth doughter of Fitzhugh. Randolff was a Prest. Died 1875. Hugh, 3rd Lord Dacre after his =::: doughter of Lord Maxwell. before his father) brother, Died 1383. GRE:YSTOCK Sir Raff, Baron of Greystoke Izabell, doughter of Lord Clyfiord. William, 4th Lord Dacre of Gilislan"1 d. 1403 Joan dougbter therl Douglas. John Lord Greystoke Elsabeth, doughter to Sir Robert Ferrers Owesley. Thomas, 5th Lord Dacre Gilsland, dyd marry daughter of Fytzhugh. * }{aft', Lord Greystoke Elsabeth, doughter to William Lord Fytzhugh. tThomas, 6th Lord Dacre Gilsland somOned by Wryt to be at Phelyppa, daughter of Raff the Parlement then holden A O 33 Henry VI. by the name Nevel!, Earl of Westmore of Thomas Dacre of Gylsland Knight. Di~d 1458. land. Sir Robert Greystock, Knight Elsabeth daughter of therl of Kent: !Sir Humfrey Dacre 3rd son.