Qualcomm Inc. V. Broadcom Corp.: 9,259,985 Reasons to Comply with Discovery Requests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insight Notes Linked to the J.P. Morgan Quest 5G Thematic Basket (Jan 2021) Due February 18, 2022 Fully and Unconditionally Guaranteed by Jpmorgan Chase & Co

The information in this preliminary pricing supplement is not complete and may be changed. This preliminary pricing supplement is not an offer to sell nor does it seek an offer to buy these securities in any jurisdiction where the offer or sale is not permitted. Subject to completion dated December 15, 2020 January , 2021 Registration Statement Nos. 333-236659 and 333-236659-01; Rule 424(b)(2) JPMorgan Chase Financial Company LLC Structured Investments Insight Notes Linked to the J.P. Morgan Quest 5G Thematic Basket (Jan 2021) due February 18, 2022 Fully and Unconditionally Guaranteed by JPMorgan Chase & Co. The notes are designed for investors who seek exposure to the performance of the J.P. Morgan Quest 5G Thematic Basket (Jan 2021) of 32 unequally weighted Reference Stocks, which we refer to as the Basket, as reduced by the Basket Deduction of 1.50%. The Reference Stocks in the Basket represent the common stocks / common shares / American depositary shares / ordinary shares of 32 U.S.-listed companies associated with the ongoing roll-out of fifth-generation wireless technologies (“5G”). Investors should be willing to forgo interest and dividend payments and, if the Basket is flat, declines or does not increase by at least 1.50%, be willing to lose some or all of their principal amount at maturity. The notes are unsecured and unsubordinated obligations of JPMorgan Chase Financial Company LLC, which we refer to as JPMorgan Financial, the payment on which is fully and unconditionally guaranteed by JPMorgan Chase & Co. Any payment on the notes is subject to the credit risk of JPMorgan Financial, as issuer of the notes, and the credit risk of JPMorgan Chase & Co., as guarantor of the notes. -

Certain Semiconductor Devices and Consumer Audiovisual Products Containing the Same That Infringe U.S

UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. In the Matter of CERTAIN SEMICONDUCTOR Investigation No. 337-TA-1047 DEVICES AND CONSUMER AUDIOVISUAL PRODUCTS CONTAINING THE SAME NOTICE OF COMMISSION DETERMINATION NOT TO REVIEW AN INITIAL DETERMINATION TERMINATING THE INVESTIGATION AS TO ONE RESPONDENT GROUP AGENCY: U.S. International Trade Commission. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: Notice is hereby given that the U.S. International Trade Commission has determined not to review an initial determination (“ID”) (Order No. 35) issued by the presiding administrative law judge (“ALJ”). FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Robert Needham, Office of the General Counsel, U.S. International Trade Commission, 500 E Street, SW., Washington, D.C. 20436, telephone (202) 708-5468. Copies of non-confidential documents filed in connection with this investigation are or will be available for inspection during official business hours (8:45 a.m. to 5:15 p.m.) in the Office of the Secretary, U.S. International Trade Commission, 500 E Street, SW., Washington, D.C. 20436, telephone (202) 205- 2000. General information concerning the Commission may also be obtained by accessing its Internet server (https://www.usitc.gov). The public record for this investigation may be viewed on the Commission's electronic docket (EDIS) at https://edis.usitc.gov. Hearing-impaired persons are advised that information on this matter can be obtained by contacting the Commission’s TDD terminal on (202) 205- 1810. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The Commission instituted this investigation on April 12, 2017, based on a complaint filed by Broadcom Corporation (“Broadcom”) of Irvine, California. 82 FR 17688. The complaint alleges violations of section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, 19 U.S.C. -

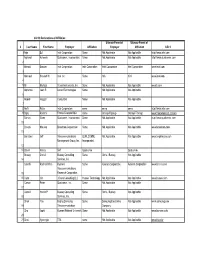

0 Last Name First Name Employer Affiliation Ultimate Parent Of

802.20 Declarations of Affiliation Ultimate Parent of Ultimate Parent of 0 Last Name First Name Employer Affiliation Employer Affiliation URL1 1 Agis Ed Intel Corporation Same Not Applicable Not Applicable http://www.intel.com Agrawal Avneesh Qualcomm, Incorporated Same Not Applicable Not Applicable http://www.qualcomm. com 2 Ahmadi Sassan Intel Corporation Intel Corporation Intel Corporation Intel Corporation www.intel.com 3 Alamouti Siavash M. Intel Inc. Same N/A N?A www.intel.com 4 5 Ali Murtaza Texas Instruments, Inc. Same Not Applicable Not Applicable www.ti.com Alphonse Jean R. Lucent Technologies Same Not Applicable Not Applicable 6 Alsaleh Haggar Consultant Same Not Applicable Not Applicable 7 8 Arefi Reza Intel Corporation same same same http://www.intel.com 9 Bajaj Rashmi France Telecom R&D same Orange Ftgroup OrangeFTGroup www.francetelecom.com/en Barriac Gwen Qualcomm, Incorporated Same Not Applicable Not Applicable http://www.qualcomm. com 10 Bavafa Moussa Broadcom Corporation Same Not Applicable Not Applicable www.broadcom.com 11 Bernstein Jeff Telecommunications QUALCOMM, Not Applicable Not Applicable www.tmgtelecom.com Management Group, Inc. Incorporated 12 13 Bravin Nancy Self Qualcomm Qualcomm Bussey Chris J. Bussey Consulting Same Chris J Bussey Not Applicable 14 Services, Inc. Canchi Radhakrishna Kyocera Same Kyocera Corporation. Kyocera Corporation www.ktrc-na.com Telecommunications 15 Research Corporation. 16 Carlo Jim J.Carlo Consulting LLC Huawei Technology Not Applicable Not Applicable www.huawei.com Carson Peter -

BROADCOM CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on January 29, 2015 Registration No. 333- UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM S-8 REGISTRATION STATEMENT Under The Securities Act of 1933 BROADCOM CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) California 33-0480482 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 5300 California Avenue, Irvine, California 92617 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Broadcom Corporation 1998 Employee Stock Purchase Plan, as amended and restated Broadcom Corporation 2007 International Employee Stock Purchase Plan, as amended and restated (Full title of the Plans) Arthur Chong, Esq. Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary Broadcom Corporation 5300 California Avenue, Irvine, California 92617 (Name and address of agent for service) (949) 926-5000 (Telephone number, including area code, of agent for service) Copies to: Joseph M. Yaffe Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP 525 University Avenue, Suite 1100 Palo Alto, California 94301 (650) 470-4500 Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, or a smaller reporting company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” and “smaller reporting company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. (Check one): Large accelerated filer x Accelerated filer ¨ Non-accelerated filer ¨ (Do not check if a smaller reporting company) Smaller -

Broadcom Corporation (Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION PROXY STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 14(a) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Filed by the Registrant þ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ¨ Check the appropriate box: ¨ Preliminary Proxy Statement þ Definitive Proxy Statement ¨ Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ¨ Definitive Additional Materials ¨ Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-12 Broadcom Corporation (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): þ Fee not required. ¨ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(4) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ¨ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ¨ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. (1) Amount Previously Paid: (2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: (3) Filing Party: (4) Date Filed: Table of Contents BROADCOM CORPORATION 5300 California Avenue Irvine, California 92617-3038 March 29, 2013 Dear Fellow Shareholder: You are cordially invited to attend our 2013 Annual Meeting of Shareholders, which will be held at Broadcom’s corporate headquarters, 5300 California Avenue, Irvine, California, at 10:00 a.m. -

United States District Court, D. Delaware. INTEL

Untitled Document 3/3/10 12:53 AM United States District Court, D. Delaware. INTEL CORPORATION, Plaintiff. v. BROADCOM CORPORATION, Defendant. No. 00-796-RRM Nov. 6, 2001. In construing claims of patent for computer communications system including a communication medium, a plurality of nodes coupled to the communication medium, and a transfer format selection means for selecting a format for the transfer of data between nodes, the District Court, McKelvie, J., held that: (1) phrase "communication medium" was a collection of connections in a communication system over which information could be transmitted; (2) "plurality of nodes" did not have to be coupled, or electronically connected, to the communication medium; and (3) preamble language was language of intended use and did not serve to limit the meaning of the claim. Claims construed. 4,823,201, 4,975,830, 5,079,630, 5,134,478, 5,894,410. Cited. J. Andrew Huffman, Esquire, Fish & Richardson P.C., Wilmington, DE, John E. Gartman, Esquire and Juanita Brooks, Esquire, Fish & Richardson P.C., San Diego, CA, for Plaintiff. Richard H. Morse, Esquire and John W. Shaw, Esquire, Young Conaway Stargatt & Taylor, LLP, Wilmington, DE, Ron E. Shulman, Esquire, Michael A. Ladra, Esquire, Irwin R. Gross, Esquire, and James C. Yoon, Esquire, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, Palo Alto, CA, Raphael L. Lupo, Esquire and Vera Elson, Esquire, McDermott, Will & Emery, Washington DC, for Defendant. MEMORANDUM OPINION MCKELVIE, District Judge. This is a patent case. Plaintiff Intel Corporation is a Delaware corporation with its principal place of business in Santa Clara, California. Intel owns U.S. -

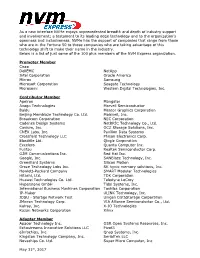

As a New Interface Nvme Enjoys Unprecedented

As a new interface NVMe enjoys unprecedented breadth and depth of industry support and involvement; a testament to its leading edge technology and to the organization’s openness and inclusiveness. NVMe has the support of companies that range from those who are in the Fortune 50 to those companies who are taking advantage of this technology shift to make their name in the industry. Below is a list of just some of the 100 plus members of the NVM Express organization. Promoter Member Cisco DellEMC NetApp Intel Corporation Oracle America Micron Samsung Microsoft Corporation Seagate Technology Microsemi Western Digital Technologies, Inc. Contributor Member Apeiron Mangstor Avago Technologies Marvell Semiconductor Baidu Mentor Graphics Corporation Beijing Memblaze Technology Co. Ltd. Mobiveil, Inc. Broadcom Corporation NEC Corporation Cadence Design Systems NetBRIC Technology Co., Ltd. Cavium, Inc. OCZ Storage Solutions, Inc. CNEX Labs, Inc. Pavilion Data Systems Crossfield Technology LLC Phison Electronics Corp. Elastifile Ltd. Qlogic Corporation Excelero Quanta Computer Inc. Fujitsu Realtek Semiconductor Corp. G2M Communications Inc. Red Hat Inc. Google, Inc. SANBlaze Technology, Inc. Greenliant Systems Silicon Motion Grace Technology Labs Inc. SK hynix memory solutions, Inc. Hewlett-Packard Company SMART Modular Technologies Hitachi, Ltd. TDK Corporation Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. Teledyne LeCroy Hyperstone GmbH Tidal Systems, Inc. International Business Machines Corporation Toshiba Corporation IP-Maker ULINK Technology, Inc. JDSU - Storage Network Test Unigen DataStorage Corporation JMicron Technology Corp. VIA Alliance Semiconductor Co., Ltd. Kalray, Inc. X-IO Technologies Kazan Networks Corporation Xilinx Adopter Member Apacer Technology Inc. OSR Open Systems Resources, Inc. Echostreams Innovative Solutions LLC Pivot3 eInfochips, Inc. Qnap Systems, Inc. -

BROADCOM CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 2, 2012 Registration No. 333-___ UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM S-8 REGISTRATION STATEMENT Under The Securities Act of 1933 BROADCOM CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) California 33-0480482 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 5300 California Avenue, Irvine, California 92617 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) NetLogic Microsystems, Inc. 2000 Stock Plan (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) NetLogic Microsystems, Inc. Amended and Restated 2004 Equity Incentive Plan (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) Optichron, Inc. 2011 Restricted Stock Unit Plan (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) NetLogic Microsystems, Inc. 2008 New Employee Inducement Incentive Plan (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) Shares Issuable Pursuant to Certain Employee Inducement Grants Made Prior to the Effectiveness of the NetLogic Microsystems, Inc. 2008 New Employee Inducement Incentive Plan (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) Aeluros, Inc. 2001 Stock Option Option/Stock Issuance Plan (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) Shares Issuable Pursuant to the Agreement and Plan of Merger Reorganization, dated May 31, 2009, by and among NetLogic Microsystems, Inc., RMI Corporation, Roadster Merger Corporation and WP VIII Representative LLC (as assumed by Broadcom Corporation) (Full title of the Plans) Arthur Chong, Esq. Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary Table of Contents Broadcom Corporation 5300 California Avenue, Irvine, California 92617 (Name and address of agent for service) (949) 926-5000 (Telephone number, including area code, of agent for service) Copies to: Joseph M. Yaffe Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP 525 University Avenue, Suite 1100 Palo Alto, California 94301 (650) 470-4500 Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, or a smaller reporting company. -

Weekly PTAB Statistics December 5, 2016

Weekly PTAB Statistics December 5, 2016 Week of Dec 5 IPR CBM PGR 47 2 0 29 6 0 11 0 0 0 0 0 Dec 2016 3 9 1 0 0 0 0 0 70 36 16 7 YTD 2016 654 60 84 26 1,592 24 821 56 996 63 22 IPR New Petitions (Week of Dec. 5) IPR # Arctic Cat, Inc. v. Polaris Industries Inc. IPR2017-00455 Daimler AG v. Stragent, LLC IPR2017-00458 Daimler AG v. Stragent, LLC IPR2017-00457 EMC Corporation v. ActivIdentity, Inc. IPR2017-00338 Google Inc. v. Koninklijke Philips NV IPR2017-00447 Medtronic Xomed, Inc. v. Neurovision Medical Products, Inc. IPR2017-00456 Sony Corporation v. Broadcom Corporation IPR2017-00461 Arctic Cat, Inc. v. Polaris Industries Inc. IPR2017-00433 Askeladden L.L.C. v. Encoditech LLC IPR2017-00452 DISH Network LLC v. Customedia Technologies, LLC IPR2017-00454 Google Inc. v. Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV IPR2017-00437 Huawei Device Co., Ltd. v. Papst Licensing GmbH & Co., KG IPR2017-00448 Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. v. Papst Licensing GmbH & Co., KG IPR2017-00449 Inogen, Inc. v. Separation Design Group IP Holdings LLC IPR2017-00453 Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v. Boston Scientific Scimed, Inc. IPR2017-00444 Huawei Device Co., Ltd. v. Papst Licensing GmbH & Co., KG IPR2017-00443 Nautilus Hyosung Inc. v. William D Beskitt IPR2017-00426 NVIDIA Corporation v. Jong-Hoon Oh IPR2017-00381 UNIFIED PATENTS INC. v. Jakuta Diodes, LLC IPR2017-00379 Valeo North America, Inc. v. Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG IPR2017-00441 Valeo North America, Inc. v. Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG IPR2017-00442 Broadcom Limited v. -

Secured Wireless Content Transmission Over Cloud with Intelligibility

International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJEAS) ISSN: 2394-3661, Volume-2, Issue-5, May 2015 Secured Wireless Content Transmission over Cloud with Intelligibility Amit Kumar Dewangan, Sadaf Rahman We propose to give accommodation to the client through Abstract- — Information privacy can be successfully protected straight forward, justifiable yet secure correspondence through encryption. The high convenience of PDAs and tablets interfaces. Our objective is to shield date at all checkpoints is held onto by shoppers and also the corporate and open through which it ventures i.e. Sender Device Network segment. Then again, particularly in the non-shopper range the Cloud Recipient Device. element security assumes a conclusive part for the stage determination process. The majority of the present In this universe of cutting edge correspondence, individuals organizations inside of the cell phone area included an extensive variety of security components to the at first customer situated favor components through which information can be spared gadgets or have managed security as a center element from the or recovered rapidly, effectively and safely from any land earliest starting point (RIM, now BlackBerry). One of the key coordinate. To encourage this goal, PDAs and versatile security highlights for ensuring information on the gadget or in distributed computing assume an essential part. They gadget reinforcements are encryption frameworks, which are invigorate the client to utilize strategies for savvy stockpiling accessible in the greater part of current gadgets. For this reason and recovery of information utilizing foundation, stage and for existing, Android's distinctive encryption frameworks are programming as an administration being given by 3rd surveyed and their vulnerability to diverse assaults is examined gathering. -

Joyninactionmwc2012guide.Pdf

Contents What is joyn? 5 Acision 6 Acme Packet 7 Alcatel-Lucent 8 Broadcom 10 Deutsche Telekom 11 D2 Technologies 12 Ecrio 13 Ericsson 14 France Telecom/Orange 15 GSMA Rich Communications 16 HTC 17 Huawei 18 Interop Technologies 19 IP Gallery 20 IPneo 21 Jibe Mobile 22 LG Electronics 24 Mavenir 25 Metaswitch Networks 26 Neusoft 27 Newpace 28 Nokia 29 Nokia Siemens Networks 30 Samsung 31 SK Telecom 32 Solaiemes 33 Sony 34 Summit Tech 35 Telecom Italia 37 Telefonica 38 Vodafone 40 Information Disclaimer WIT Software 41 Information contained in this publication should be used as a guide only and should not be ZTE 42 relied upon as the sole source of information relating to its content. Additional sources of At a Glance - Summary of joyn exhibitors 43 information may be listed herein. No warranty, either express or implied, is made with respect Market Research Reports 47 to the information contained herein. The GSMA is not responsible for any loss, inconvenience, damage (whether special or consequential) or claims arising out of the use of the information contained in this publication. 3 What is joyn? joyn makes everyday, mobile to mobile communications more engaging. joyn brings you closer to the people in your mobile address book by combining all the ways you want to be in touch - Contacts, Chat, File share and Video share. Liven-up your everyday communication as you: ■■ Share the chat - with one-to-one and group instant messaging ■■ Share the moment - enhance calls and chat by adding in videos, pictures, music and files joyn is device and network aware which means it automatically ‘knows and shows’ the ways you can share with any of your contacts - via chat, video, call or files - at any moment in time. -

BROADCOM CORPORATION 2009 Annual Report Everything ®

BO7523 3/2/10 10:15 AM Page c BROADCOM CORPORATION 2009 Annual Report Connecting everything® BO7523 3/2/10 10:15 AM Page d Broadcom’s innovative products and technologies enable people to connect – locally and globally – for business, for fun, at home, at the office and on the move. OUR THREE MAJOR TARGET MARKETS Home: Broadband Communications Infrastructure: Enterprise Networking Hand: Mobile & Wireless ABOUT BROADCOM Broadcom Corporation is a major technology innovator and global leader in semiconductors for wired and wireless communications. Broadcom products enable the delivery of voice, video, data and multimedia to and throughout the home, the office and the mobile environment. We provide the industry’s broadest portfolio of state-of-the-art system-on-a-chip and software solutions to manufacturers of computing and networking equipment, digital entertainment and broadband access products, and mobile devices. These solutions support our core mission: Connecting everything®. Broadcom, one of the world's largest fabless communications semiconductor companies, with 2009 revenue of $4.49 billion, holds more than 3,800 U.S. and 1,550 foreign patents, and has more than 7,800 additional pending patent applications, and one of the broadest intellectual property portfolios addressing both wired and wireless transmission of voice, video, data and multimedia. A Fortune 500® company, Broadcom is headquartered in Irvine, California, and has offices and research facilities in North America, Asia and Europe. Broadcom Class A shares trade on the Nasdaq Global Select MarketSM under the symbol BRCM. BO7523 3/2/10 10:15 AM Page 1 To Our Shareholders By virtually any measure, 2009 was an extraordinary year.