Culture and Geography: South Australia's Mound Springs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park and Regional Reserve

<iframe src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/ns.html?id=GTM-5L9VKK" height="0" width="0" style="display:none;visibility:hidden"></iframe> Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park and Regional Reserve About Check the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 30092021.pdf) before visiting this park. Located within the driest region of the Australian continent, the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park is in the centre of the Simpson Desert, one of the world's best examples of parallel dunal desert. The Simpson Desert's sand dunes stretch over hundreds of kilometres and lie across the corners of three states - South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory. The Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Regional Reserve, just outside the Conservation Park, features a wide variety of desert wildlife preserved in a landscape of varied dune systems, extensive playa lakes, spinifex grasslands and acacia woodlands. The reserve links the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park to Witjira National Park. Simpson Desert parks in South Australia and Queensland are closed in summer from 1 December to 15 March. Vehicles are required to have high visibility safety flags (#safety) attached to the front of the vehicle. Opening hours Open daily. Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park and Regional Reserve are closed from 1 December to 15 March each year. Access may be restricted due to local road conditions. Please refer to the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin-30092021.pdf) for current access and road condition information. Closures and safety This park is closed on days of Catastrophic Fire Danger and may also be closed on days of Extreme Fire Danger. -

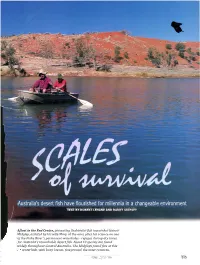

Australia's Desert Fish Have Flourished for Millennia in a Changeable Environment TEXT by ROBERT LEHANE and BARRY SKIPSEY

Australia's desert fish have flourished for millennia in a changeable environment TEXT BY ROBERT LEHANE AND BARRY SKIPSEY Afloat in the Red Centre, pioneering freshwater fish researcher Hamar Midgley, assisted by his wife Mary at the oars, plies his science on one of the Finke River's permanent waterholes - refuges during dry times I for Australia's remarkable desert fish. About 10 species are found widely throughout Central Australia. The Midgleys found five at this NT waterhole, with bony bream, foreground, the most common. APRIL - JUNE 1996 105 • CHORUS OF BIRDS had shat- are literally the gene pools of Aus- tered the icy calm of the tralia's desert fish. Like the outback's A. winter sunriseI tanhrd woken other ephemeral watercourses, the peered Finke has only a few permanent holes, flap of my swag as a warming yellow but it's in them that fish survive dry gjow rose over the Finke River water- times, dodging predators and endur- hole. With each passing minute, the ing scorching summer days and bit- red dunes bordering the opposite bank terly cold winter nights. Then, like ripened to a richer hue. desert flowers, these remnant popula- Alerted by splashing, I shifted my tions explode into life when rains gaze back to the waterhole, where I come, multiplying and dispersing with saw — to my astonishment — a pair of long-awaited floodwaters to repopu- pelicans. I'd never seen these grand late the rivers and ephemeral lakes. birds so deep in Central Australia — To learn about these tenacious ani- I was only 110 kilometres south of mals, Fa joined an expedition led by Alice Springs. -

Malacologia, 1989, 31(1): 1-140 an Endemic Radiation Of

MALACOLOGIA, 1989, 31(1): 1-140 AN ENDEMIC RADIATION OF HYDROBIID SNAILS FROM ARTESIAN SPRINGS IN NORTHERN SOUTH AUSTRALIA: THEIR TAXONOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION AND ANATOMY By W.F. Ponder, R. Hershler*, and B. Jenkins, The Australian Museum, Sydney South, NSW, 2000, Australia CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Absence of fauna The mound springs—a brief description Conservation Geomorphology and water chemistry ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Spring groups and complexes REFERENCES Climate APPENDIX 1 MATERIALS AND METHODS List of stations Taxonomy List of springs not sampled Taxonomic rationale Stations at which no hydrobiids were Materials collected Methods Locality maps Characters APPENDIX 2 Anatomy Tables of measurements Physiology Materials Methods ABSTRACT RESULTS Taxonomy Artesian springs between Marree and Fonscochlea Oodnadatta contain an endemic fauna of Fonscochlea (Wolfgangia) hydrobiid snails that have undergone an Trochidrobia adaptive radiation in which habitat parti- Anatomy tioning and size displacement are clearly Anatomical description of evident. Ten new species in two new en- Fonscochlea accepta demic genera, Fonscochlea and Trochidro- Anatomical description of bia, are described. Three of the species of Trochidrobia punicea Fonscochlea are divided into a total of six Physiology geographic forms, which are not formally named. Two geographic forms are restricted DISCUSSION to single springs, the remainder being found Evolution and relationships of fauna in several springs, spring groups, or com- Geological history plexes of springs. Fonscochlea is divided in Relationships of mound-spring inver- to two subgenera, Fonscochlea s.s. contain- tebrates ing five species and Wolfgangia with a single Evolution of species within mound species. springs Both genera are represented in most Dispersal springs, with up to five taxa present in single springs in the Freeling Springs Group and in Environmentally-induced variation some of the other springs in the northern part Ecology and behaviour of the spring system. -

Hydrogeological Overview of Springs in the Great Artesian Basin

Hydrogeological Overview of Springs in the Great Artesian Basin M. A. (Rien) Habermehl1 Abstract The Great Artesian Basin (GAB) is a regional groundwater system consisting of aquifers and confining beds within the sedimentary Eromanga, Surat and Carpentaria Basins. They under- lie arid to semi-arid regions across 1.7 million km2, or one-fifth of the Australian continent. Artesian springs of the GAB are naturally occurring outlets of groundwater from the confined aquifers. Springs predominantly occur near the eastern recharge margins and the south-western and western discharge margins of the GAB. These zones of natural groundwater discharge represent areas of permanent water, with widely recognised cultural, spiritual and subsistence importance to Indigenous people for tens of thousands of years. The unique hydrogeological environments – discharge, hydrochemistry and substrate – support a range of endemic flora and fauna protected under the EPBC Act (1999). Springs have formed in many areas across the GAB; however, the largest concentrations occur near the south-western margins of the basin. Supporting these flowing artesian springs is a multi-layered aquifer system, comprising Jurassic- to Cretaceous-age sandstones and siltstone, and confining beds of mudstones. Hydrogeological, hydrochemical and isotope hydrology studies show that most artesian springs and flowing water bores in the GAB derive their water from the main Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous Cadna-owie Formation – Hooray Sandstone aquifer and its equivalents. Focusing on springs in South Australia, this paper provides a summary of the hydrogeology of the GAB, including zones of recharge and regional groundwater flow directions, with a major focus on summarising under- standing of the occurrence and formation of springs. -

Fishes of Australia's Great Artesian Basin Springs – an Overview

Fishes of Australia’s Great Artesian Basin Springs – An Overview Adam Kerezsy1 Abstract Patterns of fish distribution within Great Artesian Basin springs fall into two distinct categories: the opportunistic colonisation of springs by widespread riverine species following flooding, and long- term habitation – and speciation – within isolated spring complexes by fishes endemic to certain spring complexes. The endemic fishes of Australia’s Great Artesian Basin springs persist in what some would consider the most unlikely fish habitats imaginable. Within predominantly hot and dry landscapes, they inhabit the only reliable wet areas, which are frequently the same temperature as the surrounding plains and as shallow as the body depth of some of the species. There are seven narrow- range fish species endemic to Great Artesian Basin springs: the Dalhousie catfishNeosiluris ( gloveri), Dalhousie hardyhead (Craterocephalus dalhousiensis), red-finned blue-eye Scaturiginichthys( vermeilipinnis), three localised species of gobies (Chlamydogobius gloveri, C. micropterus and C. squami genus) and the Dalhousie mogurnda (Mogurnda thermophila). These species occur at only three locations: Dalhousie in South Australia; and the Pelican Creek and Elizabeth springs complexes, which are both in Queensland. An eighth species, the desert goby (Chlamydogobius eremius) has a wider range across multiple spring complexes in South Australia. All GAB endemic spring species should be considered endangered due to their small ranges and small populations; however, their formal status varies widely between state, national and international legislation and/or lists. Additionally, all fish endemic to GAB springs are threatened by a broad suite of factors that endanger inland aquatic ecosystems, such as water extraction, pollution, and the possibility that alien or unwanted species may become established. -

Elizabeth Springs Is One of a Suite of Nationally Important Artesian Springs in the Great Artesian Basin, Which Is the World’S Largest Artesian Basin

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Natural Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Great Artesian Basin Springs: Elizabeth Other Names: Place ID: 105821 File No: 4/08/222/0015 Nomination Date: 09/07/2007 Principal Group: Wetlands and Rivers Status Legal Status: 09/07/2007 - Nominated place Admin Status: 30/10/2008 - Assessment by AHC completed Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Warra Distance from town 24 (km): Direction from town: S Area (ha): 145 Address: Springvale Rd, Warra, QLD LGA: Diamantina Shire QLD Location/Boundaries: About101ha, Springvale Road, 24km south of Warra, comprising Lot 1 on SP120220. Assessor's Summary of Significance: Elizabeth Springs is one of a suite of nationally important artesian springs in the Great Artesian Basin, which is the world’s largest artesian basin. The artesian springs have been the primary natural source of permanent water in most of the Australian arid zone over the last 1.8 Million years (the Pleistocene and Holocene periods). These artesian springs, also known as mound springs, provide vital habitat for more widespread terrestrial vertebrates and invertebrates with aquatic larval young, and are a unique feature of the arid Australian landscape. As these artesian springs are some distance from each other in the Australian inland, and individually each one covers a relatively tiny area, their isolation has allowed the freshwater animal lineages to evolve into distinct species, which include fish, aquatic invertebrates (crustacean and freshwater snail species) and wetland plants. This results in a high level of endemism, or species that are found nowhere else in the world. -

9 Pillars of Cobb & Co

Take time to experience Winton – Dinosaur Capital of Australia, home of Waltzing Matilda and Queensland’s Boulder Opal; a rich combination of outback life, landscapes and legend. Stay a couple of days and enjoy our country hospitality. 9 Pillars of Experience the history and mystery when visiting Boulia; land of the mysterious Min Min Light, ancient fossils, outback racing events such as horses, camels and drag cars. Cobb & Co Endless skies, wildlife and much more in the capital of the Channel Country. Things to see and do on the “9 Pillars of Cobb & Co” Winton to Boulia your notes your The drive between Winton and Boulia is one of ancient beauty and is often referred to as one of the best scenic drives in 2 – 3 day loop drive outback Queensland. Mesa rock formations or ‘Jump-ups’ are visible on either side of the road with Cawnpore Lookout offering spectacular panoramic views of the surrounding Lilleyvale Hills. Steeped in history the 9 Pillars of Cobb & Co drive offers a glimpse into our pioneering past and takes you off the beaten track. Stop for lunch at the Middleton Hotel (Pillar 4) the last remaining operating Cobb & Co staging post of the 9 Pillars. See the light at the Min Min Encounter, marvel at Elizabeth Springs, camp overnight at Diamantina National Park and wet a line in the mighty Diamantina River at Old Cork station. General Information The 9 Pillars of Cobb & Co is a loop drive approximately 833km and we suggest that you allow two to three days – more if you want to visit the many attractions in Winton and Boulia, explore national parks, swim or picnic. -

Central West Queensland National Parks Journey Guide

Queensland National Parks Central West Queensland National Parks Contents Welcome to Central West Queensland national parks Parks at a glance (facilities and activities) ..................................2 Welcome .....................................................................................3 Be adventurous! Map of Central West Queensland ................................................4 Journey Choose your escape ....................................................................5 off the beaten track over dusty Savour roads or desert dunes into Experience the Outback ..............................................................6 sunlit plains extended, wildflowers Queensland’s dry, but far from lifeless, heart. Discover a land of boom and bust ...............................................8 blossoming after rain and the freedom of sleeping out under a blanket of A Idalia National Park ...................................................................10 never-ending stars. Welford National Park ...............................................................12 Follow Lochern National Park ...............................................................14 the footsteps of superbly adapted arid-zone creatures and long-departed Forest Den National Park ...........................................................15 dinosaurs. Traverse ancient Aboriginal Bladensburg National Park ........................................................16 trading routes and the tracks of hardy explorers and resilient stockmen. Combo Waterhole Conservation -

Elizabeth Springs

Elizabeth Springs Australia is home to the largest artesian system in the world. The Great Artesian Basin, which covers more than 20 per cent of the Australian continent, has around 600 artesian spring complexes in twelve major groups. Artesian springs are the natural outlets of the extensive artesian aquifer from which the groundwater of the basin flows to the surface. Springs can range in size from only a few metres across to large clusters of freshwater pools known as ‘supergroups’. Elizabeth Springs forms part of the Springvale supergroup of springs that, with the exception of Elizabeth Springs, are largely extinct. The Elizabeth Springs complex extends over an area of approximately 400 by 500 metres. ‘Mound’ Springs Elizabeth Springs is situated approximately 300 kilometres south-southeast of Mount Isa in western Queensland. It is a complex of ‘mound’ springs, which means the groundwater flow deposits calcium and other salts from the mineral-rich waters. These deposits, combined with wind-blown sand, mud and accumulated plant debris, settle around the spring outflow forming mounds that resemble small volcanos. Great Artesian Basin groundwater movement rates are slow; between one to five metres per year. As a result some water in the centre of the basin, on the South Australian and Queensland border, is more that one million years old. Dating techniques that measure groundwater flow reveal that Great Artesian Basin springs are predominately recharged by rainfall on the Great Dividing Range on the eastern margin of the basin, where the basin’s aquifer outcrops, allowing water to percolate into the vast groundwater system. -

Profile of Dean Ah Chee

Profile of Dean Ah Chee Dean Ah Chee, Wati, Traditional Man, Senior Cultural Ranger for Irrwanyere Aboriginal Corporation, (IAC), Ranger for the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, of South Australia, I was born in Alice Springs under a tree near some old Railway Cottages, but on my birth certificate it states, 349 Railway Cottage. I now work in Witjira National Park, S A, where I am a Traditional Owner and a Native Title Claimant I am a Yankunytjatjara Pitjantjatjara man, Lower Southern Arrentre man, and Wankanguru man, through my Grandfathers and Grandmothers Traditional Cultural Lore/Law and Customs. I am an Executive Member of Irrwanyere Aboriginal Corporation who is in Co- Management partnership with the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, of South Australia. I was selected be the Senior Elders to be the Aboriginal Cultural Ranger for Irrwanyere Aboriginal Corporation. I was also selected by the one of the National Parks and Wildlife, Regional Conservators to be their Aboriginal Ranger. I am one of the Directors of the Walka Wani Aboriginal Corporation, and I have Traditional connections to the Anangu Yankatjatjara/Pitjantjatjara people in the APY Lands, and the Wankanguru people in ht e Simpson Desert., I am a Traditional Elder- Chilpie, I also have relations living in most parts of Australia. I have been involved with the negotiations and meetings for Witjira National Park since 1975 and have sign off on the Agreements, I am a Warden for DEWNR, an Aboriginal Heritage Inspector, I am also tied up in the middle of two Lores/Laws, I carry out my duty according to my Traditional Lores/Laws and the Co –Management Plan of Witjira National Park. -

Sam Nicol Et Al Article Springs

ECOLOGICA Perennial springs, such as those at Edgbaston Reserve, are fed by the Great Artesian Basin – a vast underground water storage system running for 1.7 million km2 beneath Qld, SA, NSW and the NT. Photo: Wayne Lawler/Ecopix Springing to life AUSTRALIA’S ‘PERMANENT PUDDLES’ ARE VITAL ECOSYSTEMS Deep in the blazing Australian desert, a few centimetres of water sits unobtrusively on a flat clay pan. There’s nothing around for miles but big skies, the merciless sun, cracked clay and weathered red dirt, and certainly nothing to tell you that the unimpressive puddle you’re standing next to is actually one of the great wonders of the natural world – unless Sam Nicol, Renee Rossini and Adam Kerezsy are your guides. ut here, water is life. In this case, even that is an The sheer improbability of fish living in this arid environment understatement. What makes this puddle special is that it’s is astounding. It’s hard to imagine a worse place for fish to live! Ono ordinary puddle. It’s a spring – meaning the water here Temperatures soar above 47 ˚C in summer and plummet to near- is permanent. Drought is the norm in arid and semi-arid Australia. freezing overnight in winter. The spring is just a few centimetres Even while standing in the puddle, you’re in the middle of yet deep, so there is little protection from temperature fluctuations. another drought that’s stretching the resolve of the stalwart local And although you’re technically on a floodplain, there’s no other graziers on surrounding properties.