19891722.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories?

Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? Putting the spotlight on cultural and linguistic diversity in television news and current affairs The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? report was prepared on the basis of research and support from the following people: Professor James Arvanitakis (Western Sydney University) Carolyn Cage (Deakin University) Associate Professor Dimitria Groutsis (University of Sydney) Dr Annika Kaabel (University of Sydney) Christine Han (University of Sydney) Dr Ann Hine (Macquarie University) Nic Hopkins (Google News Lab) Antoinette Lattouf (Media Diversity Australia) Irene Jay Liu (Google News Lab) Isabel Lo (Media Diversity Australia) Professor Catharine Lumby (Macquarie University) Dr Usha Rodrigues (Deakin University) Professor Tim Soutphommasane (University of Sydney) Subodhanie Umesha Weerakkody (Deakin University) This report was researched, written and designed on Aboriginal land. Sovereignty over this land was never ceded. We wish to pay our respect to elders past, present and future, and acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’ ongoing struggles for justice and self-determination. Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories? Executive summary The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? report is the first comprehensive picture of who tells, frames and produces stories in Australian television news and current affairs. It details the experience and the extent of inclusion and representation of culturally diverse news and current affairs presenters, commentators and reporters. It is also the first -

Conference Program

CONFERENCE PROGRAM 2 October 2017 // Perth, Western Australia Resources, Environment and Security in the Maritime Realm WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S PREMIER FORUM ON QUESTIONS OF REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE Running order Time Session Type and Speaker 08:30 – 09:00 REGISTRATION WITH TEA AND COFFEE 09:00 – 09:05 Conference welcome Professor L. Gordon Flake CEO of the Perth USAsia Centre 09:05 – 09:15 WA in the region The Hon. Mark McGowan Premier of Western Australia 09:15 – 09:25 Welcome to Country Dr Richard Walley Australian Indigenous Performer, Writer and Musician 09:25 – 09:30 UWA In The Zone Professor Dawn Freshwater Vice Chancellor at The University of Western Australia 09:30 – 09:50 Keynote Address The Hon. Julie Bishop Australia’s Minister for Foreign Affairs 09:50 – 10:05 Keynote Address Chris Salisbury Rio Tinto Chief Executive, Iron Ore 10:05 – 10:30 In conversation: Understanding the maritime realm – a new way of thinking Professor John Blaxland Mr Auskar Surbakti Director of the Southeast Asia Ins. & Head of Presenter and Correspondent at the Strategic & Defence Studies Centre at ANU Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Professor Erika Techera Director of the UWA Oceans Institute at The University of Western Australia 10:30 – 11:00 MORNING TEA 11:00 – 11:20 Keynote Address Senator Penny Wong Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs 11:20 - 12:05 Group discussion: Defence and security in the Indo-Pacific maritime realm Dr Dino Patti Djalal Vice Admiral Anup Singh Former Indonesian Ambassador to the US and Former Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief, -

Sydney Dog Lovers Show 2019

SYDNEY DOG LOVERS S H O W 2 0 1 9 PUBLICITY CAMPAIGN APRIL TO AUGUST 2019 COVERAGE RESULTS. 99 53 55 21 ONLINE + EDM PIECES PRINT PIECES SOCIAL PIECES BROADCAST PIECES Online coverage was achieved across national Print coverage included Sydney’s leading metro Social media coverage was achieved across Broadcast coverage was dominated by News Corp and Fairfax digital sites such as: newspapers The Daily Telegraph and Sydney Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and WeChat pieces from each major TV network News.com.au, Realestate.com.au, Daily Morning Herald, as well as News Local community platforms of major news, television, family including Nine News Sydney and Weekend Telegraph, Herald Sun, Sydney Morning Herald titles and regional newspapers. media and What’s On platforms. TODAY, Seven News and The Morning Show, and The Age. 10 News First and Studio 10 and ABC News HHME secured front covers in three regional titles: These included realestate.com.au, 9 News Sydney (syndicated nationally). Coverage was also secured across leading digital Rouse Hill Times, Fairfield City Champion and the Sydney, City of Sydney, Broadsheet, Time lifestyle and event sites such as Broadsheet, Time Newcastle Star. Out, Ella’s List and Vision China Times. Radio coverage consisted of an interview Out and Concrete Playground, with syndication Magazine coverage included Jetstar Magazine, with 2GB – Breakfast and a major giveaways across their EDMs and social media channels. Family Travel Magazine, Life Begins At and dog- with Australia’s No.1 Breakfast program, Kyle & Jackie O, and Nova 96.9 – Smallzy’s Key NSW and local council listings were also specific title, Barker’s Bazaar. -

Rethinking Australian Journalism in the 1960S: the 1966-67 Work Value Case and the Sydney Newspaper Strike

Rethinking Australian journalism in the 1960s: The 1966-67 work value case and the Sydney newspaper strike John Myrtle* Contents Part 1: The 1966-67 work value case for journalists ............................................................................. 1 Application for a full-bench hearing ...................................................................................... 5 The judgment ....................................................................................................................... 6 Downgrading as an issue for journalists ................................................................................ 8 Part 2: The 1967 Sydney newspaper strike ......................................................................................... 10 The strike widens ................................................................................................................ 13 Production of the proprietors’ newspapers during the strike ................................................ 16 The Sunday News ..................................................................................................................... 16 The role of John Fairfax and Sons ............................................................................................ 17 Production at John Fairfax and Sungravure ............................................................................ 18 Production at Australian Consolidated Press .......................................................................... 18 News Limited ........................................................................................................................... -

Chapter Nine: the Main Event – Round Three – 1981-1990

Chapter Nine: The Main Event – Round Three – 1981-1990: Introduction: This chapter concludes the examination of the inextricable melding of Television Audience Survey Ratings, Financial Returns and Local ‘Live’ Production. While there was still intense rivalry between TVW7 and STW9, other forces were coming into operation in the succeeding period from 1981-1990. In this decade both TVW7 and STW9 were subsumed by much larger corporate entities. At the level of programming this led to a notable decline in local ‘live’ production, as a result of national networking and a corresponding diminution of community responsibility. During this period there were to be big changes in the structure of what can be termed the era of the two ‘family television’ companies in Western Australia. The chapter examines the events that led to TVW7 becoming part of the Robert Holmes a’ Court Bell Group, the retirement of Sir James Cruthers (considered by many to be ‘the Father’ of Perth television) and the sale of STW9 to the Bond Corporation. Another development, the introduction of the Aussat Satellite System was to have a huge impact on program transmission and in conjunction with Networking, perhaps deliver the mortal blow to the local ‘live’ television industry. The chapter concludes with the first two years of a three-station System in Western Australia’s capital city, when NEW10 went on air in 1988. Examination of the correlation between audience ratings surveys and Company profitability continues and so are their combined deleterious effects upon the former showcases of the two original stations, their respective Production Departments and the wealth of output from their in-house studios. -

5249 Remarkable Mag V6.Indd

WOMENREMARKABLE an audience with Jessica Rowe – 2018 PROGRAM – MESSAGE FROM THE PRINCIPAL MRS FRAN REDDAN elcome to the 2018 Today, we continue to live and breathe At each biennial event, we induct a small Remarkable Women Series that ethos through our new Mission for number of ‘Remarkable Women’ into WGala Dinner. This year we 2018 to ‘empower our students to aspire our ‘Hall of Fame’; alumnae who have are honoured to welcome Australian to excellence, to make a difference and, been nominated by our community journalist, author, television presenter as enterprising global citizens, rise boldly in recognition of their exceptional and women’s rights and mental health to the opportunities of their times’. We contribution to their field of endeavour advocate, Jessica Rowe. believe it has never been a better time for in Australia and beyond. women to thrive and take their place as Since the first day of class in 1899 when role models and leaders in our society. Tonight, we are honoured to induct just five Mentone Girls took their place And in doing so, we should celebrate three very special, unique women. in history, to today’s thriving community their achievements along the way. of over 7,000 students and ‘Old Girls’, I thank you for your engagement and we have held fast to the philosophy of the We have a long history of pioneering support of our School and we hope you founding Simpson sisters, “to be bold, to women, and our Remarkable Women enjoy this wonderful evening. do one’s best and to never give in” and Series is designed to bring their stories Mrs Fran Reddan this year we are calling on our students to to life, to inspire our students and our Principal “believe, achieve and succeed”. -

•NGT May 06.Indd

banners by the gate and using people he had met in the last the Peacebus.com PA spoke couple of days. Grist news Cyanide Watch – On the road to the workers as they arrived While there another media An enormous patch Graeme Dunstan At the front gate we were on site. call came in, ABC Radio, and eager for news especially after We told them that our I handed the cell phone over of plastic trash swirls he Rain Corroboree an ambulance came by. When argument was not with them to Kevin and sat by playing in the Pacific Ocean at Easter was the the ambulance came back, but rather with Barrick Gold with a baby and listened as most graceful and thankfully empty, we pestered and the corporately corrupt he described the camp to the hen it was a kid, potentT Earth defence I have the driver for the story. NSW Labor government interviewer as something Wthe Pacific Ocean been part of in many a long He told us of the lock- (the “Carr-Macquarie Bank- wondrous. Handing back the always wanted a Garbage year. The camp was set on the on and how the police Iemma” Government) who phone Kevin grumbled: “You Patch of its very own. dry plain and up against the commander, Inspector Kevin had approved it. We gave are making me a media star.” Now it’s got one: a patch back door of the Barrick Gold Hutley in person had spent them warning that the But that is what Barrick is of trash, at least twice the mine and it bedecked with two hours carefully and mine would certainly be propagating as I write this? size of Texas (!), floating flags (the Rainbow Chai tent patiently cutting Paul free. -

Australian Commercial Television, Identity and the Imagined Community

Australian Commercial Television, Identity and the Imagined Community Greg Levine Bachelor of Media (Honours), Macquarie University, 2000 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Media, Division o f Society, Culture, Media and Philosophy Macquarie University, Sydney February 2007 1 MAC O.UAICI I HIGHER DEGREE THESIS AUTH O R’S CONSENT DOCTORAL This is to certify that I, Cx.............. ¥f/.C>L^r.............................. being a candidate for the degree of Doctor of ... V ................................................... am aware of the policy of the University relating to the retention and use of higher degree theses as contained in the University’s Doctoral Degree Rules generally, and in particular rule 7(10). In the light of this policy and the policy of the above Rules, I agree to allow a copy of my thesis to be deposited in the University Library for consultation, loan and photocopying forthwith. ...... Signature of Candidate Signature of Witness Date this................... 9*3.......................................day o f ...... ..................................................................2qO _S£ MACQUARIE A tl* UNIVERSITY W /// The Academic Senate on 17 February 2009 resolved that Gregory Thomas Levine had satisfied the requirements for admission to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. This thesis represents a major part of the prescribed program of study. L_ Contents Synopsis 3 Declaration 4 Acknowledgements 5 Introduction 6 1. Methodology 17 2. New Media or Self-Reflexive Identities 22 3. The Imagined Community: a Theoretical Study 37 4. Meta-Aussie: Theories of Narrative and Australian National Identity 66 5. The Space of Place: Theories of “Local” Community and Sydney 100 6. Whenever it Snows: Australia and the Asian Region 114 7. -

John Lyons Joins Abc News

Media Release JOHN LYONS JOINS ABC NEWS JOHN Lyons, one of Australia's leading journalists, is to join ABC News as Head Investigative and In-depth Journalism. He will lead Australia's premier current affairs teams and programs across broadcast and digital, including 7.30, Australian Story, Four Corners, Q&A, Insiders, Offsiders, Lateline, Foreign Correspondent, Behind the News, AM, PM, The World Today and Correspondents Report, as well as finding the best ways to deliver the ABC's finest investigative and long- form content to new audiences. A three-time Walkley Award winner, Lyons' previous roles include being the Editor of The Sydney Morning Herald, Executive Producer of the Nine Network's Sunday program, a foreign correspondent in Washington, New York and Jerusalem and, currently, Associate Editor (Digital Content) at News Corp's The Australian. ABC Director, News Gaven Morris said Lyons was an outstanding editorial leader. "As platforms and channels change, information outlets multiply and fake news proliferates, the demand for trusted sources of information, well-told stories and quality, news-breaking journalism is greater than ever," he said. "The centrepiece at ABC News is always the journalism, and John will play a key role in delivering our best in-depth and investigative reporting to all Australian audiences when, where and how they want to consume it." Lyons said: "After ten great years at The Australian, I'm delighted to be joining the ABC in this important role at a time when independent public interest journalism is more vital than ever. "With people increasingly getting their news and information through different means, it is crucial we are able to present strong investigative journalism on digital platforms. -

Happy Birthday to All the Horses! See Inside

The only way to fi nd out what’s going on! Serving the Hunter for over 20 years with a readership of over 4,000 weekly! Thursday 10th August, 2017 Missed an issue? www.huntervalleyprinting.com.au/Pages/Entertainer.php Happy birthday to all the horses! See inside Driving the Hunter for 60 years! TV Guide Happy Horses Birthday Celebrate the Horses' Birthday in the Horse Capital of Australia at the Scone Country Markets To book a stall please call 6540 1300 or email A big blue horse sculpture and pony rides will be at Scone Country Markets [email protected] for a stall holder form. on August 12 as part of celebrations for horses birthday month. www.upperhuntercountry.com Birthday cake, games and a sausage sizzle will also be part of the celebrations at the Scone Visitor Information and Horse Centre (VIC) for an equine-themed market day from 12pm to 4pm. For more information or to apply for a stall contact the Scone VIC on 6540 1300 or email [email protected] Image: Big Blue by Nick Adams. SESSION TIMES: THURSDAY 10 AUGUST - WEDNESDAY 16 AUGUST Cinema is CLOSED Mondays outside of school and public holidays ANNABELLE: VALERIAN AND THE CITY CREATION OF A THOUSAND PLANETS ATOMIC BLONDE (MA15+) 109mins (M) 137mins (MA15+) 115mins Thu, Fri & Tues Thu, Fri & Tues Thu, Fri & Tues 11.35am, 3.50pm & 8.45pm 3D: 9.00am, 1.50pm & 6.30pm 11.40am, 1.40pm & 9.15pm Sat, Sun & Wed Sat, Sun & Wed Sat, Sun & Wed 12.40pm, 4.30pm & 7.00pm 2D: 9.00am & 1.50pm 3D: 6.40pm 11.40am, 2.45pm & 9.10pm WAR FOR THE PLANET DUNKIRK MICKEY AND COMING SOON OF THE APES (M) 106mins Logan Lucky : The Dark Tower (M) 140mins THE ROADSTAR American Made : It Thu, Fri & Tues RACES The Hitmans Body Guard Thu, Fri & Tues (G) 50mins 9.00am & 6.30pm 4.30pm The Emoji Movie : Captain Underpants 12-15 Sydney Street Kingsman : Golden Circle Sat, Sun & Wed Sat, Sun & Wed Sat & Sun Muswellbrook 9.00am & 9.20pm 5.00pm 11.35am Phone: (02) 4044 0600 Live in Muswellbrook? Don’t forget the Courtesy Bus is available to get you to the cinema. -

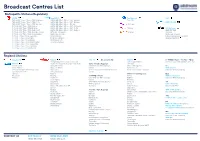

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

2014 Annual Report and Shareholder Review May Australia

20 AnnualAPN NEWS & MEDIA LIMITED Report ABN 95 008 637 643 14 In 2014, APN continued to evolve its business through integration, diversification and investment in growth categories. Our goal for 2015 is to outperform in each of the markets that our businesses operate in. We have identified the regions, the audiences and the businesses where we want to invest. CONTENTS Highlights 2 Senior Management Team 24 Financial Statements 55 About APN 4 Board of Directors 26 Directors’ Declaration 107 Chairman’s Report 6 Corporate Governance Statement 29 Independent Auditor’s Report 108 CEO’s Report 8 Directors’ Report 36 Shareholder Information 110 Operating and Financial Review 10 Remuneration Report 40 Five Year Financial History 112 Corporate Social Responsibility 22 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 54 Corporate Directory IBC APN NEWS & MEDIA LIMITED AND CONTROLLED ENTITIES 1 ANNUAL REPORT 20 14 AGM Notice is hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of members of APN News & Media Limited will be held at the Four Seasons Hotel Sydney, 199 George Street, Sydney NSW 2000 on Wednesday, 6 May 2015 at 11am. APN NEWS & MEDIA LIMITED ABN 95 008 637 643 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Highlights APN News & Media is a growth oriented media, entertainment and technology company with assets in Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong. Australian Radio Network LARGEST AUDIENCE Hong Kong Outdoor OF ANY METROPOLITAN Buspak and Cody RADIO NETWORK IN AUSTRALIA FM SYDNEY #1 STATION iHeartRadio 1,700 ADELAIDE HONG KONG #1 STATION IsLAND BUSES 632,052 BRIsbANE REGISTERED USERS #1 STATION 60 IN AUSTRALIA in 7/8 surveys Signature buses AND NEW ZEALAND with integrated media offerings 1,200 864,473 buzplay multimedia MOBILE DOWNLOAds installations OVER 160 BILLBOARDS SIX prime locations APN NEWS & MEDIA LIMITED AND CONTROLLED ENTITIES 3 New Zealand Media and Entertainment NZME.