Dr. Karen Jaffe: Hi Everyone, and Thanks for Joining Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1:03-Cv-03578 Document #: 199 Filed: 09/08/06 Page 1 of 136 Pageid

Case: 1:03-cv-03578 Document #: 199 Filed: 09/08/06 Page 1 of 136 PageID #:<pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) Case No. 03 C 3578 ) v. ) Magistrate Judge Morton Denlow ) QT, INC., Q-RAY COMPANY, ) BIO-METAL, INC., QUE TE PARK, ) a.k.a. ANDREW Q. PARK, and ) JUNG JOO PARK, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER “The pain just went away.” “Within seconds the pain was gone.” “You don’t have to live with pain.” The Q-Ray® Ionized Bracelet® (“Q-Ray bracelet”) achieved tremendous commercial success through a series of 30-minute infomercials. The Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) brings this action claiming Defendants marketed the Q-Ray bracelet in a deceptive and misleading manner by representing that the bracelet provides immediate, significant or complete pain relief and scientific tests prove their pain-relief claims. Defendants deny their advertising was false or misleading. They contend adequate substantiation exists for the advertising claims made in connection with the promotion and sale of the Q-Ray bracelet. Case: 1:03-cv-03578 Document #: 199 Filed: 09/08/06 Page 2 of 136 PageID #:<pageID> The Court conducted a seven-day bench trial between June 6 and July 11, 2006. The Court has carefully considered the testimony of the witnesses who testified in person and by deposition, the Joint Stipulations of Fact for Trial, the exhibits introduced into evidence, the written submissions of the parties, and the oral arguments of counsel. The counsel on both sides presented the case in a highly professional manner. -

October 1983

VOL. 7, NO. 10 Cover Photo by Rick Malkin FEATURES ALEX VAN HALEN Rock musicians are often accused of being more concerned with the rock 'n' roll lifestyle than with the music. That lifestyle is very much a part of Alex Van Halen's image, but underneath that image is a serious musician who has a lot to say about drums and drumming, and he says it here in this MD exclusive. by Robyn Flans 8 PHILLIP WILSON For a drummer to have played with such diverse groups as The Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band indicates that his musicianship is not limited in any way, and that is certainly true of Phillip Wilson, who has a knack for weaving seemingly contrasting influences together into one unique style. by Chip Stern 16 DRUMS AROUND THE WORLD Japan's Stomu Yamash'ta; England's Ronnie Verrell; Brazil's Ivan Conti; Canada's Steve Negus; Israel's Aron Kaminski; Den- mark's Alex Riel. 20 FRANK BEARD In this revealing interview, Frank Beard, the unpretentious, self-taught drummer for ZZ Top, discusses his career from his early emulations of '60s British rock bands, to his later involvement with a psychedelic group, and his present position as a member of the highly successful, Texas-based rock trio. by Susan Alexander 26 ROCK CHARTS COLUMNS "Lowdown In the Street" PROFILES 74 by James Morton ON THE MOVE Nelson Montana 30 ROCK PERSPECTIVES A Left-Handed Perspective REVIEWS EDUCATION by Robert Doyle 92 ON TRACK 94 CLUB SCENE STRICTLY TECHNIQUE PRINTED PAGE 96 Handling the Ups and Downs Triplets With Buzz Rolls 46 by Joe Morello by Rick Van Horn 100 NEWS COMPLETE PERCUSSIONIST UPDATE Junkanoo EQUIPMENT by Robyn Flans 110 by Neil M. -

A Conversation with Suzy Bogguss by Frank Goodman (12/2007, Puremusic.Com) What a Singer. When, Only Now and Then, a Singer's Ba

A Conversation with Suzy Bogguss by Frank Goodman (12/2007, puremusic.com) What a singer. When, only now and then, a singer's basic sound is completely arresting, it's like a wake up call. You can have attitude, you can be dramatic, elastic or gymnastic-- but when you have that sound, you can just sing, and it's all there. You can dial in degrees of whatever else you want, but that's just icing on the cake. And it's the cake they call angel's or devil's food, right? A dozen or so albums into a charmed career, Suzy says she's just realizing she's actually the thread that ties it all together, not whether she's singing Country, or Swing, or Jazzy Pop. And the last of those is the place where Sweet Danger goes with assured poise. Though most of her fantastic work has been in the Country vein, her fans followed her when she cut the landmark Swing record with her old friend Ray Benson and past and present members of Asleep At The Wheel. It's a cinch that they will be along for the ride here to witness Suzy absolutely killing the great Beth Nielsen Chapman and Annie Roboff song "Right Back Into The Feeling," or the mindblowing cover of the Peter Cetera classic "If You Leave Me Now." Sometimes you don't really get how great a singer is until they come out of the bag that made them famous. We said jazzy pop, but at times it feels also like a really great soft rock album. -

QT and R-Ray Memorandum Opinion and Order

Case 1:03-cv-03578 Document 199 Filed 09/08/2006 Page 1 of 136� IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) Case No. 03 C 3578 ) v. ) Magistrate Judge Morton Denlow ) QT, INC., Q-RAY COMPANY, ) BIO-METAL, INC., QUE TE PARK, ) a.k.a. ANDREW Q. PARK, and ) JUNG JOO PARK, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER “The pain just went away.” “Within seconds the pain was gone.” “You don’t have to live with pain.” The Q-Ray® Ionized Bracelet® (“Q-Ray bracelet”) achieved tremendous commercial success through a series of 30-minute infomercials. The Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) brings this action claiming Defendants marketed the Q-Ray bracelet in a deceptive and misleading manner by representing that the bracelet provides immediate, significant or complete pain relief and scientific tests prove their pain-relief claims. Defendants deny their advertising was false or misleading. They contend adequate substantiation exists for the advertising claims made in connection with the promotion and sale of the Q-Ray bracelet. Case 1:03-cv-03578 Document 199 Filed 09/08/2006 Page 2 of 136� The Court conducted a seven-day bench trial between June 6 and July 11, 2006. The Court has carefully considered the testimony of the witnesses who testified in person and by deposition, the Joint Stipulations of Fact for Trial, the exhibits introduced into evidence, the written submissions of the parties, and the oral arguments of counsel. The counsel on both sides presented the case in a highly professional manner. -

COPING with FTD by Cindy Odell

COPING WITH FTD by Cindy Odell I have the interesting experience of addressing FTD from two different directions. I have been the caregiver for three family members, my grandmother, my mother and my aunt. My grandmother’s third child, my uncle, also died from dementia but I was never his caregiver. All four of these family members were diagnosed with “dementia” and it was assumed that it was Alzheimer’s, but no biopsy or autopsy was performed on any of them. Not much was known about FTD at that time and, unfortunately, it still is unknown to the majority of people. Knowing what I do now, I firmly believe they each had FTD, not Alzheimer’s. My symptoms are mirroring theirs perfectly. After the death of my mother, and early into my aunt’s battle with dementia, when I was in my early 50’s, I was also diagnosed with FTD. Since I was in the earlier stages, it helped immensely that I was helping to care for my aunt at the same time because I understood the disease much better since I was dealing with it myself and was able to be much more patient with her. I am quite fortunate that I can still read and write. Several people have suggested that I consider writing a book. My husband has had a book published, so I know how much stress is involved in the process. I also would rather provide my insights and opinions free of charge. I do not claim to have all the answers, especially since no two cases of FTD are identical. -

Shenandoah, Iowa 45 Cents

( SHENANDOAH, IOWA 45 CENTS VOL. 49 MARCH, 1985 NUMBER3 PAGE2 KITCHEN-KLATTER MAGAZINE, MARCH, 1985 Kitchen-Klatter (USPS 296-300) (Reg. U.S. Pat. Off.) MAGAZINE "More Than Just Paper And Ink" Leanna Field Driftmier, Founder Lucile Driftmier Vemess, Publisher Subscription Price $5.00 per year (12 issues) in the U.S.A. Foreign Countries, $6.00 Advertising rates made known on application. Entered as second class matter May 21, 1937, at the post office at Shenandoah, Iowa, under theActofMarch3, 1879. Published monthly at The Driftmier Company Shenandoah, Iowa 51601 Copyright 1985 by The Driftmier Company. LEnER FROM JULIANA Dear Friends, This morning's paper gave me the first real clue that spring is on the way. Katharine Lowey, daughter of Juliana and Jed Lowey, enjoys playing her guitar. Several pages were devoted to full-page We hope many of you heard her play it on the Kitchen-Klatter Homemaker Radio advertisements for baseball and softball Program the day before Christmas. equipment. I do feel sorry for the adver the February Kitchen-Klatter Magazine. relief from the bustle of Athens. After a tisers because anyone interested in this The next time I see Martin we'll have to leisurely dinner at our hotel we browsed equipment would take one look out the compare notes on this interesting site. through the many little shops selling window and forget the whole thing. It is One thing that struck me was that the souveniers. I'll mention in passing that snowing. The wind is blowing and I know huge columns in the Temple of Apollo many shops in Greece and almost all the that it is cold without even venturing out. -

This Isn't About Hats Joseph Paul Carney Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 This isn't about hats Joseph Paul Carney Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Joseph Paul, "This isn't about hats" (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16232. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16232 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 This isn't about hats Joseph Paul Carney Major Professor: Joe Geha Iowa State University "This isn't about hats" consists of four short stories, all written from a first person narrative perspective. Each story involves its narrator in some moment requiring the making of a choice: to take sides between loved ones, to commit to love, to make or ignore social connections. Issues these stories explore include budding and failing romances, a cross-cultural encounter, and being raised under and growing away from a crumbling marriage. This isn't about hats by Joseph Paul Carney A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment ofthe requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English -

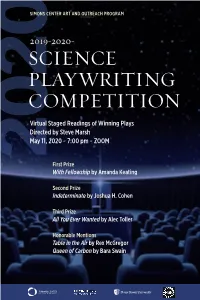

Science Playwriting Competition Calls for Ten-Minute Plays with a Substantial Science Component

SIMONS CENTER ART ANDSIMO OUTREACH PROGRAM 2019-2020- SCIENCE PLAYWRITING COMPETITION Virtual Staged Readings of Winning Plays Directed by Steve Marsh May 11, 2020 ~ 7:00 pm ~ ZOOM 2020 First Prize With Fellowship by Amanda Keating Second Prize Indeterminate by Joshua H. Cohen Third Prize All You Ever Wanted by Alec Toller Honorable Mentions Table in the Air by Rex McGregor Queen of Carbon by Bara Swain TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 Introduction 6 Awards 7 Playwright Bios 8 With Fellowship* by Amanda Keating 26 Indeterminate by Joshua H. Cohen 33 All You Ever Wanted by Alec Toller 41 Table In The Air by Rex McGregor 47 Queen Of Carbon by Bara Swain * Play contains some strong language CONTENTS This competition was made possible by the generous support of the Simons Center for Geometry and Physics, The C.N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics, and the National Science Foundation. INTRODUCTION Bringing science and theatre together provides the inspiration for plays of exceptional artistic merit that lead to exciting new ways of learning about science. Indeed, we believe the best science plays can be great works of art because of their ability to aesthetically express scientific concepts that may result in further explorations in both domains. They also have potential as educational tools rooted in their artistic expression. Thus, science and theatre may learn from each other, through their common goals of investigating and gaining knowledge by means of experimentation. The SCGP Science Playwriting Competition calls for ten-minute plays with a substantial science component. The contest is open to students, faculty, and interested writers worldwide. -

Cannabis Helps with Their PTSD

Public Comments Received about PTSD on the ADHS Website for the July 2013 Petitions I recently attended the International Drug Policy Reform Conference in Denver Colorado. There, I attended multiple panels concerning drug and veterans issues, particularly related to PTSD and the potential treatment that medical marijuana has to offer those suffering from it. Much of the relevant information on how this can be achieved may be found here: http://veteransformedicalmarijuana.org/content/general-use-cannabis-ptsd- symptoms As a young person and a college student, I am fully aware of how many of my peers have served and are currently serving in theaters of war. Me and everyone else in the country will need to be responsible enough to care for veterans for the rest of our lives. This can play a part in that. I implore the AZDHS to do the right thing. Please do not deny relief to the men and women who deserve and have earned it. Respectfully, Scott B. Cecil Students for Sensible Drug Policy Board of Directors HAD MY DAD HAD THIS OPTION FOR THE PTSD HE SUFFERED AFTER SURVIVING DEC 7TH BOMBING OF PEARL HARBOR, HIS LIFE AS AN ALCOHOLIC COULD HAVE BEEN SPENT CALMER, MORE PRODUCTIVE. THE VETS COMING HOME FROM IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN NEED THIS AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO DRUGS AND ALCOHOL/ the debilitating effects of PTSD can be treated with heavy Narcotics.that render the patient dependent on the stuff and that makes the side effects turn you into a Zombe ...with the use of Medical Marijuana I am able to live a reasonably productive life without the side effects ....while I use different strains for different uses .....would hate to have to go back to Narcotics I can take one strain that gets me uplifted in the beginning of the day and another that helps with the sleeping and minimizes the Night sweats and Nightmares Why?Because a no would be a big [profanity] you to all our soldiers that have been screwed over and sent on multiple tours to fight for this country and now need good medicine to have some quality of life. -

A Harmonic Analysis of Saxophonist Ralph Moore Found Through

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 7-2017 A Harmonic Analysis of Saxophonist Ralph Moore Found Through Common Characteristics In Four Solo Transcriptions of Jazz Standards From 1991-1998 Patrick Brown University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Brown, Patrick, "A Harmonic Analysis of Saxophonist Ralph Moore Found Through Common Characteristics In Four Solo Transcriptions of Jazz Standards From 1991-1998" (2017). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 111. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/111 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Harmonic Analysis of Saxophonist Ralph Moore Found Through Common Characteristics In Four Solo Transcriptions of Jazz Standards From 1991-1998 By Patrick Brown A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For The Degree of Doctor of Music Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Paul Haar Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2017 A Harmonic Analysis of Saxophonist Ralph Moore Found Through Common Characteristics In Four Solo Transcriptions of Jazz Standards From 1991-1998 Patrick Brown, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2017 Adviser: Paul Haar Saxophonist Ralph Moore has performed with jazz luminaries such as Horace Silver, Roy Haynes, Freddie Hubbard, and J.J. -

Methadone Maintenance Treatment: Client Handbook

methadone maintenance treatment methadone clclientient maintenance hhandbookandbook treatment REVISED client handbook REVISED A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre acknowledgments Methadone Maintenance Treatment Client Handbook REVISED The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) wishes to ISBN: 978-0-88868-699-2 (PRINT) acknowledge the valuable and enthusiastic participation of ISBN: 978-0-88868-700-5 (PDF) methadone clients from across Ontario in the development of this ISBN: 978-0-88868-701-2 (HTML) handbook. Clients suggested what information we should include, they provided us with straight-up quotations about their experience Printed in Canada and advice, and they reviewed and commented on the draft copy. Copyright © 2001, 2003, 2008 • Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Their involvement helped us to create a book that we believe will interest, inform and empower methadone clients throughout No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form Ontario. Due to the restrictions of confidentiality we cannot list the or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and names of the many clients who participated in the project, so recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation instead we offer this expression of our earnest appreciation and (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. gratitude for their contribution. For more information on addiction -

Net Filtering in Canadian Libraries 46 Richard Beaudry

School Libraries in Canada Volume 27, Number 3 Fall 2009 Contents: Editorial: A reason to remember 3 Derrick Grose Veterans Affairs Canada learning resources for your school library 5 Adélard Comeau Des ressources pédagogiques d’Anciens Combattants Canada pour votre bibliothèque 11 scolaire Adélard Comeau Guardians of Remembrance 13 R.J. (Bob) Butt It informs, plants a seed, makes a connection and entertains. 15 SLiC interviews Sharon E. McKay Invisible Women: World War II Aboriginal Servicewomen in Canada 20 Grace Poulin Reading and Remembrance: arts and reading materials for educators 22 Angie Littlefield and Mary Cook, Project Managers Reading and Remembrance Everyone has stories. Pay attention. 23 Derrick Grose interviews Monique Polak In their own words 27 Elin Beaumont and the Azrieli Foundation Canadian resources to help young people remember 29 Victoria Pennell An interview with the president of CASL 39 SLiC interviews Linda Shantz-Keresztes School Library Profile Project – École Saint-Joachim, La Broquerie, Manitoba 41 Rolande Durand The virtual library as a learning hub 44 Anita Brooks Kirkland Net filtering in Canadian libraries 46 Richard Beaudry Keeping up with the latest citation standards in MLA, APA, and Chicago 49 (advertising supplement from EasyBib) Engage and grow with questions 50 Carol Koechlin and Sandi Zwaan Info to go for school libraries! 55 Linsey Hammond Annual "Munsch at Home" contest 57 ABC CANADA Literacy Foundation CASL Membership Form 59 Support the Canadian Association for School Libraries ______________________________________________________ Copyright ©2009 Canadian Association for School Libraries | Privacy Policy | Contact Us ISSN 1710-8535 School Libraries in Canada Online School Libraries in Canada Volume 27 Number 3 | 1 Contributors to School Libraries in Canada, Volume 27, Number 3.