Singers Success Path

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

Perception of Singing

Dept. for Speech, Music and Hearing Quarterly Progress and Status Report Perception of singing Sundberg, J. journal: STL-QPSR volume: 20 number: 1 year: 1979 pages: 001-048 http://www.speech.kth.se/qpsr STL-QPSR 6/1979 r, I , -1 . I. MUSICAL ACOUSTICS .- . .'' , A. PERCEPTION UF*SINGING . ' %L J. Sundberg <j. , - ,. ... .T ., ., .. , - ' .: , .$:.. , ,i... .-, "' ,, . ....,.<.,:,, '.. .... .................: :. :..... , . , . ' .' '\ Abstract 9s .This article reviews investigations of the singing voice which ,. possess an interest from a perceptional point of view. Acoustic hnction, formant frequencies, phonation, pitch, and phrasing in , singing are discussed. It is found that singing differs from speech in a highly adequate manner, k. g. for the pufpose of increasing the loudness of the voice at a minimum cost as regards vocal ef- fort. The terminology used for different type's of voice timbre . seems to depend on the properties and use of. the voice organ rather than on specific acoustic signal characteris tics. - Pr- STL-QPSR f/i979 ? c 4. partials decrease monotonically with rising frequency. As a rule of thumb a given partial is 12 dB stronger than a partial located one oc- tave higher. However, for high degrees of vocal effort this source spectrum slopes less than 12 d~/octave. With soft phonation it is I steeper than 12 d~/octave. On the other hand, the voice source ;n+rr,. spectrum slope is generally not,,dependeet on which voiced sound is produced. :: br:,iec,:.ceii~9 !: -<; c,*>iriF cat i~::5~:- I VIXJ ko 31i30e .JTT The spectral differences between various voiced sounds arise when the sound from the voice source is transferred through the vocal tract, i. -

Leading Congregational Singing Song/Hymn Leading Is an Important

Leading Congregational Singing LEADING AS A VOCALIST - Joyce Poley DEVELOPING A STYLE Song/hymn leading is an important skill that can make an enormous difference to the way a congregation sings. If the song leader is primarily a vocalist, there are a number of qualities that are important for success: having enthusiasm for singing; being able to establish a good rapport with the congregation; being comfortable with your own voice; having accurate pitch and a pleasing vocal quality; being excited about introducing new ideas and repertoire. These attributes will help ensure a good singing experience for both the leader and the congregation. Song/hymn leaders use a variety of approaches when leading the congregation, and no single approach or style is “right”. What is important is to develop a style that is unique to your own personality and comfort level. The following are some things to consider: • Energy & enthusiasm Probably nothing affects your success as a song leader as much as your own energy and enthusiasm. People respond to those who love what they do; enthusiasm truly is contagious. Those who already enjoy singing will simply become even more enthusiastic; those who are more reluctant, or feel they can’t sing, will want to be a part of all this positive energy. The more encouragement they get from the leader, the better they will sing. The better they sing, the more confident they become, and the more willing to try new things. Enjoy yourself and be at ease, and they will journey almost any distance with you into the music. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

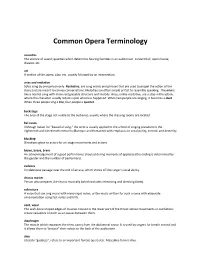

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Singing Transcription from Polyphonic Music Using Melody Contour Filtering

applied sciences Article Singing Transcription from Polyphonic Music Using Melody Contour Filtering Zhuang He and Yin Feng * Department of Artificial Intelligence, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361000, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Automatic singing transcription and analysis from polyphonic music records are essential in a number of indexing techniques for computational auditory scenes. To obtain a note-level sequence in this work, we divide the singing transcription task into two subtasks: melody extraction and note transcription. We construct a salience function in terms of harmonic and rhythmic similarity and a measurement of spectral balance. Central to our proposed method is the measurement of melody contours, which are calculated using edge searching based on their continuity properties. We calculate the mean contour salience by separating melody analysis from the adjacent breakpoint connective strength matrix, and we select the final melody contour to determine MIDI notes. This unique method, combining audio signals with image edge analysis, provides a more interpretable analysis platform for continuous singing signals. Experimental analysis using Music Information Retrieval Evaluation Exchange (MIREX) datasets shows that our technique achieves promising results both for audio melody extraction and polyphonic singing transcription. Keywords: singing transcription; audio signal analysis; melody contour; audio melody extraction; music information retrieval Citation: He, Z.; Feng, Y. Singing Transcription from Polyphonic Music 1. Introduction Using Melody Contour Filtering. The task of singing transcription from polyphonic music has always been worthy Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5913. https:// of research, and it represents one of the most difficult challenges when analyzing audio doi.org/10.3390/app11135913 information and retrieving music content. -

Using Bel Canto Pedagogical Principles to Inform Vocal Exercises Repertoire Choices for Beginning University Singers by Steven M

Using Bel Canto Pedagogical Principles to Inform Vocal Exercises Repertoire Choices for Beginning University Singers by Steven M. Groth B.M. University of Wisconsin, 2013 M.M. University of Missouri, 2017 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts College of Music 2020 1 2 3 Abstract The purpose of this document is to identify and explain the key ideals of bel canto singing and provide reasoned suggestions of exercises, vocalises, and repertoire choices that are readily available both to teachers and students. I provide a critical evaluation of the fundamental tenets of classic bel canto pedagogues, Manuel Garcia, Mathilde Marchesi, and Julius Stockhausen. I then offer suggested exercises to develop breath, tone, and legato, all based classic bel canto principles and more recent insights of voice science and physiology. Finally, I will explore and perform a brief survey into the vast expanse of Italian repertoire that fits more congruently with the concepts found in bel canto singing technique in order to equip teachers with the best materials for more rapid student achievement and success in legato singing. For each of these pieces, I will provide the text and a brief analysis of the characteristics that make each piece well-suited for beginning university students. 4 Acknowledgements Ever since my first vocal pedagogy class in my undergraduate degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I have been interested in how vocal pedagogy can best be applied to repertoire choices in order to maximize students’ achievement in the studio environment. -

THE MESSA DI VOCE and ITS EFFECTIVENESS AS a TRAINING EXERCISE for the YOUNG SINGER D. M. A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfi

THE MESSA DI VOCE AND ITS EFFECTIVENESS AS A TRAINING EXERCISE FOR THE YOUNG SINGER D. M. A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diane M. Pulte, B.M., M.M. *** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Karen Peeler Approved by Dr. C. Patrick Woliver ______________ Adviser Dr. Michael Trudeau School of Music ABSTRACT The Messa di voce and Its Effectiveness as a Training Device for the Young Singer This document is a study of the traditional Messa di voce exercise (“placing of the voice”) and it’s effectiveness as a teaching tool for the young singer. Since the advent of Baroque music the Messa di voce has not only been used as a dynamic embellishment in performance practice, but also as a central vocal teaching exercise. It gained special prominence during the 19th and early 20th century as part of the so-called Bel Canto technique of singing. The exercise demonstrates a delicate balance between changing sub-glottic aerodynamic pressures and fundamental frequency, while consistently producing a voice of optimal singing quality. The Messa di voce consists of the controlled increase and subsequent decrease in intensity of tone sustained on a single pitch during one breath. An early definition of the Messa di voce can be found in Instruction Of Mr. Tenducci To His Scholars by Guisto Tenducci (1785): To sing a messa di voce: swelling the voice, begin pianissimo and increase gradually to forte, in the first part of the time: and so diminish gradually to the end of each note, if possible. -

Le Haute-Contre En Question : Significations Socioculturelles D’Une Crise Vocale En France Autour De 1830 Olivier Bara

Le haute-contre en question : significations socioculturelles d’une crise vocale en France autour de 1830 Olivier Bara To cite this version: Olivier Bara. Le haute-contre en question : significations socioculturelles d’une crise vocale en France autour de 1830. Der Countertenor. Die männlische Falsettstimme vom Mittelalter zur Gegenwart, Schott, pp.137-154, 2012. hal-00910187 HAL Id: hal-00910187 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00910187 Submitted on 27 Nov 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Le haute-contre en question : significations socioculturelles d’une crise vocale en France autour de 1830 Olivier Bara Université Lyon 2 - Unité Mixte de Recherche LIRE (CNRS-Lyon 2) Sans doute y a-t-il quelque esprit de paradoxe dans le choix d’évoquer, dans un colloque consacré au contre-ténor, la voix de ténor. Il ne s’agit pas, toutefois, de prendre le contre-pied de cette recherche collective : plutôt de jouer en contrepoint et de convoquer le cas particulier du haute-contre français au moment de sa remise en question. Sera examiné, plus précisément, le passage de l’aigu émis en falsetto ou en falsettone, en voix de tête ou en voix mixte, à l’aigu chanté en voix de poitrine. -

Note by Martin Pearlman the Castrato Voice One of The

Note by Martin Pearlman © Martin Pearlman, 2020 The castrato voice One of the great gaps in our knowledge of "original instruments" is in our lack of experience with the castrato voice, a voice type that was at one time enormously popular in opera and religious music but that completely disappeared over a century ago. The first European accounts of the castrato voice, the high male soprano or contralto, come from the mid-sixteenth century, when it was heard in the Sistine Chapel and other church choirs where, due to the biblical injunction, "let women remain silent in church" (I Corinthians), only men were allowed to sing. But castrati quickly moved beyond the church. Already by the beginning of the seventeenth century, they were frequently assigned male and female roles in the earliest operas, most famously perhaps in Monteverdi's L'Orfeo and L'incoronazione di Poppea. By the end of that century, castrati had become popular stars of opera, taking the kinds of leading heroic roles that were later assigned to the modern tenor voice. Impresarios like Handel were able to keep their companies afloat with the star power of names like Farinelli, Senesino and Guadagni, despite their extremely high fees, and composers such as Mozart and Gluck (in the original version of Orfeo) wrote for them. The most successful castrati were highly esteemed throughout most of Europe, even though the practice of castrating young boys was officially forbidden. The eighteenth-century historian Charles Burney described being sent from one Italian city to another to find places where the operations were performed, but everyone claimed that it was done somewhere else: "The operation most certainly is against law in all these places, as well as against nature; and all the Italians are so much ashamed of it, that in every province they transfer it to some other." By the end of the eighteenth century, the popularity of the castrato voice was on the decline throughout Europe because of moral and humanitarian objections, as well as changes in musical tastes.