The Evolution of the Heldentenor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

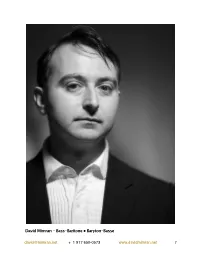

Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 1 100 Words Bio

David Mimran - Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 www.davidmimran.net 1 100 words bio Bass-Baritone David Mimran set aside a career as a lawyer in Paris to sing opera in New York. Great vocal flexibility in a wide tessitura, natural acting skills and a knowledge of nine languages including Italian, French, German, English, Spanish and Finnish allow for a large variety of repertoire. Roles on stage include Alcindoro/Benoît in Bohème, Conte Ceprano in Rigoletto, Niejus & Cascada in Merry Widow, Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte, Figaro & Antonio in Le nozze di Figaro, Morales & Zuniga in Carmen, Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Frank in Fledermaus, Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi, Achille in Giulio Cesare and Melisso in Alcina. Languages French: Mother tongue English: Bilingual German, Italian, Spanish: Proficient Finnish, Portuguese, Hebrew: Working knowledge Russian, Hungarian: Basic phonetic reading knowledge I would consider studying a new language to sing a role. Stage Experience Full roles performed • Benoît/Alcindoro in Bohème - Opera Company of Brooklyn • Sciarrone/Jailer in Tosca - Regina Opera • Yakuside in Madama Butterfly - Bleecker Street Opera • Niejus and Cascada in The Merry Widow - Amore Opera • Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte - NY Lyric Opera Theater • Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia - Bleecker Street Opera • Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Spinelloccio/Nicolao in Gianni Schicchi - Regina Opera • Achilla in Giulio Cesare - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Docteur -

Cantabile Hendrik Waelput

Cantabile for 4 Violas Hendrik Waelput (1845–1885) AVS Publications 018 Preface The Flemish composer and conductor Hendrik Waelput studied music at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels and was awarded the Prix de Rome for his cantata Het woud in 1867. Waelput was active as a conductor in several European cities before returning to his home town of Ghent in 1875. There, he conducted various orchestras and taught harmony and counterpoint at the Conservatory in Antwerp. Waelput’s compositions include larger forms (operas, symphonies, and choral music) and chamber music, including a string quintet (viola quintet), a Canzonetta for string quartet, and this Cantabile for four violas. While the impetus behind this particular work is unknown, his use of four identical instruments in a composition is not unique: he also wrote an Andante Cantabile for four trombones and featured four solo cellos in the Andante Cantabile movement of his Flute Concerto. This edition is based on an undated manuscript score and set of parts housed in the Library Conservatorium Ghent, BG. David M. Bynog, editor Cantabile for 4 violas Hendrik Waelput Edited by David M. Bynog Andante Cantabile Viola 1 # œ œ. œ œ > œ œ œ 3 œ. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ & 4 œ. œ œ œ 3 cresc. p œ Viola 2 œ œ œ œ œ #œ #œ œ > œ B # 3 ˙ œ ˙ œ œ œ# ˙ 4 cresc. p Viola 3 # œ bœ B 43 œ ˙ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ #œ #œ œ œ nœ œ œ > cresc. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Performance Practice Bibliography (1995-1996)

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 11 Number 2 Fall Performance Practice Bibliography (1995-1996) Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons (1996) "Performance Practice Bibliography (1995-1996)," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 2, Article 11. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.199609.02.11 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss2/11 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERFORMANCE PRACTICE BIBLIOGRAPHY (1995-1996)* Contents Surveys 212 The Ninth to Thirteenth Century 215 The Sixteenth Century 215 The Seventeenth Century 219 The Early Eighteenth Century 225 The Late Eighteenth Century 229 The Nineteenth Century 232 The Twentieth Century 235 Reflections on Performance Practice 238 SURVEYS Voices 1. Giles, Peter. The History and Technique of the Coun- ter-Tenor: a Study of the Male High Voice Family. Hants (England): Scolar Press, 1994, xxiv-459p. (ISBN 85967 931 4). Considers all high male voice types: falsetto, castrato, countertenor, male alto, male soprano. For Giles the true countertenor is a falsetto male alto who has developed a bright, clear tone. The countertenor head-voice uses the full length of folds and has developed "pharyngeal" singing between the basic and falsetto mechanisms. That "upper falsetto" (to which Caccini and others were averse) is the true falsetto is a misconception. As Rene Jacobs has indicated head- Containing as well a number of earlier citations.