Contemporary Perspectives on the Countertenor: Interviews with Kai Wessel, Corinna Herr, Arnold Jacobshagen, and Matthias Echternach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Falsetto Head Voice Tips to Develop Head Voice

Volume 1 Issue 27 September 04, 2012 Mike Blackwood, Bill Wiard, Editors CALENDAR Current Songs (Not necessarily “new”) Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight Spiritual Medley Home on the Range You Raise Me Up Just in Time Question: What’s the difference between head voice and falsetto? (Contunued) Answer: Falsetto Notice the word "falsetto" contains the word "false!" That's exactly what it is - a false impression of the female voice. This occurs when a man who is naturally a baritone or bass attempts to imitate a female's voice. The sound is usually higher pitched than the singer's normal singing voice. The falsetto tone produced has a head voice type quality, but is not head voice. Falsetto is the lightest form of vocal production that the human voice can make. It has limited strength, tones, and dynamics. Oftentimes when singing falsetto, your voice may break, jump, or have an airy sound because the vocal cords are not completely closed. Head Voice Head voice is singing in which the upper range of the voice is used. It's a natural high pitch that flows evenly and completely. It's called head voice or "head register" because the singer actually feels the vibrations of the sung notes in their head. When singing in head voice, the vocal cords are closed and the voice tone is pure. The singer is able to choose any dynamic level he wants while singing. Unlike falsetto, head voice gives a connected sound and creates a smoother harmony. Tips to Develop Head Voice If you want to have a smooth tone and develop a head voice singing talent, you can practice closing the gap with breathing techniques on every note. -

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

Perception of Singing

Dept. for Speech, Music and Hearing Quarterly Progress and Status Report Perception of singing Sundberg, J. journal: STL-QPSR volume: 20 number: 1 year: 1979 pages: 001-048 http://www.speech.kth.se/qpsr STL-QPSR 6/1979 r, I , -1 . I. MUSICAL ACOUSTICS .- . .'' , A. PERCEPTION UF*SINGING . ' %L J. Sundberg <j. , - ,. ... .T ., ., .. , - ' .: , .$:.. , ,i... .-, "' ,, . ....,.<.,:,, '.. .... .................: :. :..... , . , . ' .' '\ Abstract 9s .This article reviews investigations of the singing voice which ,. possess an interest from a perceptional point of view. Acoustic hnction, formant frequencies, phonation, pitch, and phrasing in , singing are discussed. It is found that singing differs from speech in a highly adequate manner, k. g. for the pufpose of increasing the loudness of the voice at a minimum cost as regards vocal ef- fort. The terminology used for different type's of voice timbre . seems to depend on the properties and use of. the voice organ rather than on specific acoustic signal characteris tics. - Pr- STL-QPSR f/i979 ? c 4. partials decrease monotonically with rising frequency. As a rule of thumb a given partial is 12 dB stronger than a partial located one oc- tave higher. However, for high degrees of vocal effort this source spectrum slopes less than 12 d~/octave. With soft phonation it is I steeper than 12 d~/octave. On the other hand, the voice source ;n+rr,. spectrum slope is generally not,,dependeet on which voiced sound is produced. :: br:,iec,:.ceii~9 !: -<; c,*>iriF cat i~::5~:- I VIXJ ko 31i30e .JTT The spectral differences between various voiced sounds arise when the sound from the voice source is transferred through the vocal tract, i. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Research 5-8-2021 The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera Samuel Sherman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/honors Recommended Citation Sherman, Samuel, "The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 47. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/honors/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Northern Colorado Greeley, Colorado The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for Graduation with Honors Distinction and the Degree of Bachelor of Music Samuel W. Sherman School of Music May 2021 Signature Page The Voice of Androgyny: A Gender Analysis of the Countertenor Within Opera PREPARED BY: Samuel Sherman APPROVED BY THESIS ADVISOR: _ Brian Luedloff HONORS DEPT LIAISON:_ Dr. Michael Oravitz HONORS DIRECTIOR: Loree Crow RECEIVED BY THE UNIVERSTIY THESIS/CAPSONTE PROJECT COMMITTEE ON: May 8th, 2021 1 Abstract Opera, as an art form and historical vocal practice, continues to be a field where self-expression and the representation of the human experience can be portrayed. However, in contrast to the current societal expansion of diversity and inclusion movements, vocal range classifications within vocal music and its use in opera are arguably exclusive in nature. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

How to Read Choral Music.Pages

! How to Read Choral Music ! Compiled by Tim Korthuis Sheet music is a road map to help you create beautiful music. Please note that is only there as a guide. Follow the director for cues on dynamics (volume) and phrasing (cues and cuts). !DO NOT RELY ENTIRELY ON YOUR MUSIC!!! Only glance at it for words and notes. This ‘manual’ is a very condensed version, and is here as a reference. It does not include everything to do with reading music, only the basics to help you on your way. There may be !many markings that you wonder about. If you have questions, don’t be afraid to ask. 1. Where is YOUR part? • You need to determine whether you are Soprano or Alto (high or low ladies), or Tenor (hi men/low ladies) or Bass (low men) • Soprano is the highest note, followed by Alto, Tenor, (Baritone) & Bass Soprano NOTE: ! Alto If there is another staff ! Tenor ! ! Bass above the choir bracket, it is Bracket usually for a solo or ! ! ‘descant’ (high soprano). ! Brace !Piano ! ! ! • ! The Treble Clef usually indicates Soprano and Alto parts o If there are three notes in the Treble Clef, ask the director which section will be ‘split’ (eg. 1st and 2nd Soprano). o Music written solely for women will usually have two Treble Clefs. • ! The Bass Clef indicates Tenor, Baritone and Bass parts o If there are three parts in the Bass Clef, the usual configuration is: Top - Tenor, Middle - Baritone, Bottom – Bass, though this too may be ‘split’ (eg. 1st and 2nd Tenor) o Music written solely for men will often have two Bass Clefs, though Treble Clef is used for men as well (written 1 octave higher). -

Common Opera Terminology

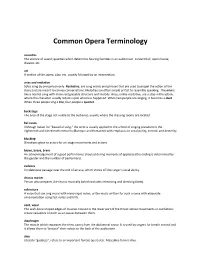

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

Classification of Voice Modality Using Electroglottogram Waveforms

Classification of Voice Modality using Electroglottogram Waveforms Michal Borsky1, Daryush D. Mehta2, Julius P. Gudjohnsen1, Jon Gudnason1 1 Center for Analysis and Design of Intelligent Agents, Reykjavik University 2 Center for Laryngeal Surgery & Voice Rehabilitation, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Subjective voice quality assessment has a long and success- ful history of usage in the clinical practice of voice disorder It has been proven that the improper function of the vocal analysis. Historically, several standards have been proposed folds can result in perceptually distorted speech that is typically and worked with in order to grade the dysphonic speech. One identified with various speech pathologies or even some neuro- popular auditory-perceptual grading protocol is termed GR- logical diseases. As a consequence, researchers have focused BAS [3], which comprises five qualities - grade (G), breath- on finding quantitative voice characteristics to objectively as- iness (B), roughness (R), asthenicity (A), and strain (S). An- sess and automatically detect non-modal voice types. The bulk other popular grading protocol is the CAPE-V [4] which com- of the research has focused on classifying the speech modality prises of auditory-perceptual dimensions of voice quality that by using the features extracted from the speech signal. This include overall dysphonia (O), breathiness (B), roughness (R), paper proposes a different approach that focuses on analyz- and strain (S). These qualitative characteristics are typically ing the signal characteristics of the electroglottogram (EGG) rated subjectively by trained personnel who then relate their au- waveform. -

Kenneth E. Querns Langley Doctor of Philosophy

Reconstructing the Tenor ‘Pharyngeal Voice’: a Historical and Practical Investigation Kenneth E. Querns Langley Submitted in partial fulfilment of Doctor of Philosophy in Music 31 October 2019 Page | ii Abstract One of the defining moments of operatic history occurred in April 1837 when upon returning to Paris from study in Italy, Gilbert Duprez (1806–1896) performed the first ‘do di petto’, or high c′′ ‘from the chest’, in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. However, according to the great pedagogue Manuel Garcia (jr.) (1805–1906) tenors like Giovanni Battista Rubini (1794–1854) and Garcia’s own father, tenor Manuel Garcia (sr.) (1775–1832), had been singing the ‘do di petto’ for some time. A great deal of research has already been done to quantify this great ‘moment’, but I wanted to see if it is possible to define the vocal qualities of the tenor voices other than Duprez’, and to see if perhaps there is a general misunderstanding of their vocal qualities. That investigation led me to the ‘pharyngeal voice’ concept, what the Italians call falsettone. I then wondered if I could not only discover the techniques which allowed them to have such wide ranges, fioritura, pianissimi, superb legato, and what seemed like a ‘do di petto’, but also to reconstruct what amounts to a ‘lost technique’. To accomplish this, I bring my lifelong training as a bel canto tenor and eighteen years of experience as a classical singing teacher to bear in a partially autoethnographic study in which I analyse the most important vocal treatises from Pier Francesco Tosi’s (c.