And Innovative Research of Emerging Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differential Geometry

Differential Geometry J.B. Cooper 1995 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 CURVES AND SURFACES—INFORMAL DISCUSSION 2 1.1 Surfaces ................................ 13 2 CURVES IN THE PLANE 16 3 CURVES IN SPACE 29 4 CONSTRUCTION OF CURVES 35 5 SURFACES IN SPACE 41 6 DIFFERENTIABLEMANIFOLDS 59 6.1 Riemannmanifolds .......................... 69 1 1 CURVES AND SURFACES—INFORMAL DISCUSSION We begin with an informal discussion of curves and surfaces, concentrating on methods of describing them. We shall illustrate these with examples of classical curves and surfaces which, we hope, will give more content to the material of the following chapters. In these, we will bring a more rigorous approach. Curves in R2 are usually specified in one of two ways, the direct or parametric representation and the implicit representation. For example, straight lines have a direct representation as tx + (1 t)y : t R { − ∈ } i.e. as the range of the function φ : t tx + (1 t)y → − (here x and y are distinct points on the line) and an implicit representation: (ξ ,ξ ): aξ + bξ + c =0 { 1 2 1 2 } (where a2 + b2 = 0) as the zero set of the function f(ξ ,ξ )= aξ + bξ c. 1 2 1 2 − Similarly, the unit circle has a direct representation (cos t, sin t): t [0, 2π[ { ∈ } as the range of the function t (cos t, sin t) and an implicit representation x : 2 2 → 2 2 { ξ1 + ξ2 =1 as the set of zeros of the function f(x)= ξ1 + ξ2 1. We see from} these examples that the direct representation− displays the curve as the image of a suitable function from R (or a subset thereof, usually an in- terval) into two dimensional space, R2. -

An Approach on Simulation of Involute Tooth Profile Used on Cylindrical Gears

BULETINUL INSTITUTULUI POLITEHNIC DIN IAŞI Publicat de Universitatea Tehnică „Gheorghe Asachi” din Iaşi Volumul 66 (70), Numărul 2, 2020 Secţia CONSTRUCŢII DE MAŞINI AN APPROACH ON SIMULATION OF INVOLUTE TOOTH PROFILE USED ON CYLINDRICAL GEARS BY MIHĂIȚĂ HORODINCĂ “Gheorghe Asachi” Technical University of Iaşi, Faculty of Machine Manufacturing and Industrial Management Received: April 6, 2020 Accepted for publication: June 10, 2020 Abstract. Some results on theoretical approach related by simulation of 2D involute tooth profiles on spur gears, based on rolling of a mobile generating rack around a fixed pitch circle are presented in this paper. A first main approach proves that the geometrical depiction of each generating rack position during rolling can be determined by means of a mathematical model which allows the calculus of Cartesian coordinates for some significant points placed on the rack. The 2D involute tooth profile appears to be the internal envelope bordered by plenty of different equidistant positions of the generating rack during a complete rolling. A second main approach allows the detection of Cartesian coordinates of this internal envelope as the best approximation of 2D involute tooth profile. This paper intends to provide a way for a better understanding of involute tooth profile generation procedure. Keywords: tooth profile; involute; generating rack; simulation. 1. Introduction Gear manufacturing is a major topic in industry due to a large scale utilization of gears for motion transmissions and speed reducers. Commonly the flank gear surface on cylindrical toothed wheels (gears) is described by two Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] 22 Mihăiţă Horodincă orthogonally curves: an involute as flank line (in a transverse plane) and a profile line. -

On the Topology of Hypocycloid Curves

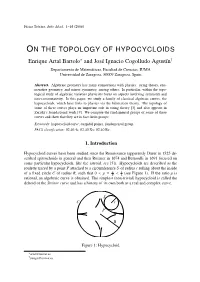

Física Teórica, Julio Abad, 1–16 (2008) ON THE TOPOLOGY OF HYPOCYCLOIDS Enrique Artal Bartolo∗ and José Ignacio Cogolludo Agustíny Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, IUMA Universidad de Zaragoza, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain Abstract. Algebraic geometry has many connections with physics: string theory, enu- merative geometry, and mirror symmetry, among others. In particular, within the topo- logical study of algebraic varieties physicists focus on aspects involving symmetry and non-commutativity. In this paper, we study a family of classical algebraic curves, the hypocycloids, which have links to physics via the bifurcation theory. The topology of some of these curves plays an important role in string theory [3] and also appears in Zariski’s foundational work [9]. We compute the fundamental groups of some of these curves and show that they are in fact Artin groups. Keywords: hypocycloid curve, cuspidal points, fundamental group. PACS classification: 02.40.-k; 02.40.Xx; 02.40.Re . 1. Introduction Hypocycloid curves have been studied since the Renaissance (apparently Dürer in 1525 de- scribed epitrochoids in general and then Roemer in 1674 and Bernoulli in 1691 focused on some particular hypocycloids, like the astroid, see [5]). Hypocycloids are described as the roulette traced by a point P attached to a circumference S of radius r rolling about the inside r 1 of a fixed circle C of radius R, such that 0 < ρ = R < 2 (see Figure 1). If the ratio ρ is rational, an algebraic curve is obtained. The simplest (non-trivial) hypocycloid is called the deltoid or the Steiner curve and has a history of its own both as a real and complex curve. -

Around and Around ______

Andrew Glassner’s Notebook http://www.glassner.com Around and around ________________________________ Andrew verybody loves making pictures with a Spirograph. The result is a pretty, swirly design, like the pictures Glassner EThis wonderful toy was introduced in 1966 by Kenner in Figure 1. Products and is now manufactured and sold by Hasbro. I got to thinking about this toy recently, and wondered The basic idea is simplicity itself. The box contains what might happen if we used other shapes for the a collection of plastic gears of different sizes. Every pieces, rather than circles. I wrote a program that pro- gear has several holes drilled into it, each big enough duces Spirograph-like patterns using shapes built out of to accommodate a pen tip. The box also contains some Bezier curves. I’ll describe that later on, but let’s start by rings that have gear teeth on both their inner and looking at traditional Spirograph patterns. outer edges. To make a picture, you select a gear and set it snugly against one of the rings (either inside or Roulettes outside) so that the teeth are engaged. Put a pen into Spirograph produces planar curves that are known as one of the holes, and start going around and around. roulettes. A roulette is defined by Lawrence this way: “If a curve C1 rolls, without slipping, along another fixed curve C2, any fixed point P attached to C1 describes a roulette” (see the “Further Reading” sidebar for this and other references). The word trochoid is a synonym for roulette. From here on, I’ll refer to C1 as the wheel and C2 as 1 Several the frame, even when the shapes Spirograph- aren’t circular. -

Some Curves and the Lengths of Their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs. 2021. hal-03236909 HAL Id: hal-03236909 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03236909 Preprint submitted on 26 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Department of Applied Science and Technology Politecnico di Torino Here we consider some problems from the Finkel's solution book, concerning the length of curves. The curves are Cissoid of Diocles, Conchoid of Nicomedes, Lemniscate of Bernoulli, Versiera of Agnesi, Limaçon, Quadratrix, Spiral of Archimedes, Reciprocal or Hyperbolic spiral, the Lituus, Logarithmic spiral, Curve of Pursuit, a curve on the cone and the Loxodrome. The Versiera will be discussed in detail and the link of its name to the Versine function. Torino, 2 May 2021, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4732881 Here we consider some of the problems propose in the Finkel's solution book, having the full title: A mathematical solution book containing systematic solutions of many of the most difficult problems, Taken from the Leading Authors on Arithmetic and Algebra, Many Problems and Solutions from Geometry, Trigonometry and Calculus, Many Problems and Solutions from the Leading Mathematical Journals of the United States, and Many Original Problems and Solutions. -

The Materiality & Ontology of Digital Subjectivity

THE MATERIALITY & ONTOLOGY OF DIGITAL SUBJECTIVITY: GRIGORI “GRISHA” PERELMAN AS A CASE STUDY IN DIGITAL SUBJECTIVITY A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada Copyright Gary Larsen 2015 Theory, Culture, and Politics M.A. Graduate Program September 2015 Abstract THE MATERIALITY & ONTOLOGY OF DIGITAL SUBJECTIVITY: GRIGORI “GRISHA” PERELMAN AS A CASE STUDY IN DIGITAL SUBJECTIVITY Gary Larsen New conditions of materiality are emerging from fundamental changes in our ontological order. Digital subjectivity represents an emergent mode of subjectivity that is the effect of a more profound ontological drift that has taken place, and this bears significant repercussions for the practice and understanding of the political. This thesis pivots around mathematician Grigori ‘Grisha’ Perelman, most famous for his refusal to accept numerous prestigious prizes resulting from his proof of the Poincaré conjecture. The thesis shows the Perelman affair to be a fascinating instance of the rise of digital subjectivity as it strives to actualize a new hegemonic order. By tracing first the production of aesthetic works that represent Grigori Perelman in legacy media, the thesis demonstrates that there is a cultural imperative to represent Perelman as an abject figure. Additionally, his peculiar abjection is seen to arise from a challenge to the order of materiality defended by those with a vested interest in maintaining the stability of a hegemony identified with the normative regulatory power of the heteronormative matrix sustaining social relations in late capitalism. -

Geometry of Algebraic Curves

Geometry of Algebraic Curves Fall 2011 Course taught by Joe Harris Notes by Atanas Atanasov One Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 E-mail address: [email protected] Contents Lecture 1. September 2, 2011 6 Lecture 2. September 7, 2011 10 2.1. Riemann surfaces associated to a polynomial 10 2.2. The degree of KX and Riemann-Hurwitz 13 2.3. Maps into projective space 15 2.4. An amusing fact 16 Lecture 3. September 9, 2011 17 3.1. Embedding Riemann surfaces in projective space 17 3.2. Geometric Riemann-Roch 17 3.3. Adjunction 18 Lecture 4. September 12, 2011 21 4.1. A change of viewpoint 21 4.2. The Brill-Noether problem 21 Lecture 5. September 16, 2011 25 5.1. Remark on a homework problem 25 5.2. Abel's Theorem 25 5.3. Examples and applications 27 Lecture 6. September 21, 2011 30 6.1. The canonical divisor on a smooth plane curve 30 6.2. More general divisors on smooth plane curves 31 6.3. The canonical divisor on a nodal plane curve 32 6.4. More general divisors on nodal plane curves 33 Lecture 7. September 23, 2011 35 7.1. More on divisors 35 7.2. Riemann-Roch, finally 36 7.3. Fun applications 37 7.4. Sheaf cohomology 37 Lecture 8. September 28, 2011 40 8.1. Examples of low genus 40 8.2. Hyperelliptic curves 40 8.3. Low genus examples 42 Lecture 9. September 30, 2011 44 9.1. Automorphisms of genus 0 an 1 curves 44 9.2. -

Math 632: Algebraic Geometry Ii Cohomology on Algebraic Varieties

MATH 632: ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY II COHOMOLOGY ON ALGEBRAIC VARIETIES LECTURES BY PROF. MIRCEA MUSTA¸TA;˘ NOTES BY ALEKSANDER HORAWA These are notes from Math 632: Algebraic geometry II taught by Professor Mircea Musta¸t˘a in Winter 2018, LATEX'ed by Aleksander Horawa (who is the only person responsible for any mistakes that may be found in them). This version is from May 24, 2018. Check for the latest version of these notes at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~ahorawa/index.html If you find any typos or mistakes, please let me know at [email protected]. The problem sets, homeworks, and official notes can be found on the course website: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mmustata/632-2018.html This course is a continuation of Math 631: Algebraic Geometry I. We will assume the material of that course and use the results without specific references. For notes from the classes (similar to these), see: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~ahorawa/math_631.pdf and for the official lecture notes, see: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mmustata/ag-1213-2017.pdf The focus of the previous part of the course was on algebraic varieties and it will continue this course. Algebraic varieties are closer to geometric intuition than schemes and understanding them well should make learning schemes later easy. The focus will be placed on sheaves, technical tools such as cohomology, and their applications. Date: May 24, 2018. 1 2 MIRCEA MUSTA¸TA˘ Contents 1. Sheaves3 1.1. Quasicoherent and coherent sheaves on algebraic varieties3 1.2. Locally free sheaves8 1.3. -

Curves with Rational Chord-Length Parametrization

Curves with rational chord-length parametrization J. Sanchez-Reyes , L. Fernandez-Jambrina Instituto de Matemdtica Aplicada a la Ciencia e Ingenieria, ETS Ingenieros Industrials, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Campus Universitario, 13071-Ciudad Real, Spain ETSI Navales, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, Arco de la Victoria s/n, 28040-Madrid, Spain Abstract It has been recently proved that rational quadratic circles in standard Bezier form are parameterized by chord-length. If we consider that standard circles coincide with the isoparametric curves in a system of bipolar coordinates, this property comes as a straightforward consequence. General curves with chord-length parametrization are simply the analogue in bipolar coordinates of nonparametric curves. This interpretation furnishes a compact explicit expression for all planar curves with rational chord-length parametrization. In addition to straight lines and circles in standard form, they include remarkable curves, such as the equilateral hyperbola, Lemniscate of Bernoulli and Limacon of Pascal. The extension to 3D rational curves is also tackled. Keywords: Bezier circle; Bipolar coordinates; Chord-length parametrization; Equilateral hyperbola; Lemniscate of Bernoulli 1. Chord-length parametrization Given a parametric curve p(t) over a certain domain t e[a,b], its chord-length at a given point p(7) is defined as (Farm, 2001, 2006): IF|p(0 — A| chord(0 := y A = p(fl), B = p(Z?) (1) |p(0-A| + |p(0-B| where bars denote the modulus of a vector. The curve is said to be chord-length parameterized if chord(f) = t. Chord- length parametrization is clearly invariant with respect to linear transformations of the domain. -

Generating Negative Pedal Curve Through Inverse Function – an Overview *Ramesha

© 2017 JETIR March 2017, Volume 4, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Generating Negative pedal curve through Inverse function – An Overview *Ramesha. H.G. Asst Professor of Mathematics. Govt First Grade College, Tiptur. Abstract This paper attempts to study the negative pedal of a curve with fixed point O is therefore the envelope of the lines perpendicular at the point M to the lines. In inversive geometry, an inverse curve of a given curve C is the result of applying an inverse operation to C. Specifically, with respect to a fixed circle with center O and radius k the inverse of a point Q is the point P for which P lies on the ray OQ and OP·OQ = k2. The inverse of the curve C is then the locus of P as Q runs over C. The point O in this construction is called the center of inversion, the circle the circle of inversion, and k the radius of inversion. An inversion applied twice is the identity transformation, so the inverse of an inverse curve with respect to the same circle is the original curve. Points on the circle of inversion are fixed by the inversion, so its inverse is itself. is a function that "reverses" another function: if the function f applied to an input x gives a result of y, then applying its inverse function g to y gives the result x, and vice versa, i.e., f(x) = y if and only if g(y) = x. The inverse function of f is also denoted. -

SERRE DUALITY and APPLICATIONS Contents 1

SERRE DUALITY AND APPLICATIONS JUN HOU FUNG Abstract. We carefully develop the theory of Serre duality and dualizing sheaves. We differ from the approach in [12] in that the use of spectral se- quences and the Yoneda pairing are emphasized to put the proofs in a more systematic framework. As applications of the theory, we discuss the Riemann- Roch theorem for curves and Bott's theorem in representation theory (follow- ing [8]) using the algebraic-geometric machinery presented. Contents 1. Prerequisites 1 1.1. A crash course in sheaves and schemes 2 2. Serre duality theory 5 2.1. The cohomology of projective space 6 2.2. Twisted sheaves 9 2.3. The Yoneda pairing 10 2.4. Proof of theorem 2.1 12 2.5. The Grothendieck spectral sequence 13 2.6. Towards Grothendieck duality: dualizing sheaves 16 3. The Riemann-Roch theorem for curves 22 4. Bott's theorem 24 4.1. Statement and proof 24 4.2. Some facts from algebraic geometry 29 4.3. Proof of theorem 4.5 33 Acknowledgments 34 References 35 1. Prerequisites Studying algebraic geometry from the modern perspective now requires a some- what substantial background in commutative and homological algebra, and it would be impractical to go through the many definitions and theorems in a short paper. In any case, I can do no better than the usual treatments of the various subjects, for which references are provided in the bibliography. To a first approximation, this paper can be read in conjunction with chapter III of Hartshorne [12]. Also in the bibliography are a couple of texts on algebraic groups and Lie theory which may be beneficial to understanding the latter parts of this paper. -

Report No. 26/2008

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 26/2008 Classical Algebraic Geometry Organised by David Eisenbud, Berkeley Joe Harris, Harvard Frank-Olaf Schreyer, Saarbr¨ucken Ravi Vakil, Stanford June 8th – June 14th, 2008 Abstract. Algebraic geometry studies properties of specific algebraic vari- eties, on the one hand, and moduli spaces of all varieties of fixed topological type on the other hand. Of special importance is the moduli space of curves, whose properties are subject of ongoing research. The rationality versus general type question of these spaces is of classical and also very modern interest with recent progress presented in the conference. Certain different birational models of the moduli space of curves have an interpretation as moduli spaces of singular curves. The moduli spaces in a more general set- ting are algebraic stacks. In the conference we learned about a surprisingly simple characterization under which circumstances a stack can be regarded as a scheme. For specific varieties a wide range of questions was addressed, such as normal generation and regularity of ideal sheaves, generalized inequalities of Castelnuovo-de Franchis type, tropical mirror symmetry constructions for Calabi-Yau manifolds, Riemann-Roch theorems for Gromov-Witten theory in the virtual setting, cone of effective cycles and the Hodge conjecture, Frobe- nius splitting, ampleness criteria on holomorphic symplectic manifolds, and more. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 14xx. Introduction by the Organisers The Workshop on Classical Algebraic Geometry, organized by David Eisenbud (Berkeley), Joe Harris (Harvard), Frank-Olaf Schreyer (Saarbr¨ucken) and Ravi Vakil (Stanford), was held June 8th to June 14th. It was attended by about 45 participants from USA, Canada, Japan, Norway, Sweden, UK, Italy, France and Germany, among of them a large number of strong young mathematicians.