Importance of Integrating Nanotechnology with Pharmacology and Physiology for Innovative Drug Delivery and Therapy – an Illustration with Firsthand Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Propranolol-Mediated Attenuation of MMP-9 Excretion in Infants with Hemangiomas

Supplementary Online Content Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol-mediated attenuation of MMP-9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4773 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics Protein Name Prop 12 mo/4 Pred 12 mo/4 Δ Prop to Pred mo mo Myeloperoxidase OS=Homo sapiens GN=MPO 26.00 143.00 ‐117.00 Lactotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=LTF 114.00 205.50 ‐91.50 Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MMP9 5.00 36.00 ‐31.00 Neutrophil elastase OS=Homo sapiens GN=ELANE 24.00 48.00 ‐24.00 Bleomycin hydrolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=BLMH 3.00 25.00 ‐22.00 CAP7_HUMAN Azurocidin OS=Homo sapiens GN=AZU1 PE=1 SV=3 4.00 26.00 ‐22.00 S10A8_HUMAN Protein S100‐A8 OS=Homo sapiens GN=S100A8 PE=1 14.67 30.50 ‐15.83 SV=1 IL1F9_HUMAN Interleukin‐1 family member 9 OS=Homo sapiens 1.00 15.00 ‐14.00 GN=IL1F9 PE=1 SV=1 MUC5B_HUMAN Mucin‐5B OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC5B PE=1 SV=3 2.00 14.00 ‐12.00 MUC4_HUMAN Mucin‐4 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC4 PE=1 SV=3 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 HRG_HUMAN Histidine‐rich glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=HRG 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 PE=1 SV=1 TKT_HUMAN Transketolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TKT PE=1 SV=3 17.00 28.00 ‐11.00 CATG_HUMAN Cathepsin G OS=Homo -

Broad and Thematic Remodeling of the Surface Glycoproteome on Isogenic

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/808139; this version posted October 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Broad and thematic remodeling of the surface glycoproteome on isogenic cells transformed with driving proliferative oncogenes Kevin K. Leung1,5, Gary M. Wilson2,5, Lisa L. Kirkemo1, Nicholas M. Riley2,4, Joshua J. Coon2,3, James A. Wells1* 1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA Departments of Chemistry2 and Biomolecular Chemistry3, University of Wisconsin- Madison, Madison, WI, 53706, USA 4Present address Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 94305, USA 5These authors contributed equally *To whom correspondence should be addressed bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/808139; this version posted October 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract: The cell surface proteome, the surfaceome, is the interface for engaging the extracellular space in normal and cancer cells. Here We apply quantitative proteomics of N-linked glycoproteins to reveal how a collection of some 700 surface proteins is dramatically remodeled in an isogenic breast epithelial cell line stably expressing any of six of the most prominent proliferative oncogenes, including the receptor tyrosine kinases, EGFR and HER2, and downstream signaling partners such as KRAS, BRAF, MEK and AKT. -

Chapter 3: Phenotypic Characterisation of Melanotransferin Knockout Mouse and Down-Regulation of Melanotransferrin in Melanoma Cells

CHAPTER 3: PHENOTYPIC CHARACTERISATION OF MELANOTRANSFERIN KNOCKOUT MOUSE AND DOWN-REGULATION OF MELANOTRANSFERRIN IN MELANOMA CELLS “An ignorant person is one who doesn't know what you have just found out.” Will Rogers, 1879 - 1935 This Chapter is published in: 1. Sekyere, E.O., Dunn, L.L., Suryo Rahmanto, Y., and Richardson, D.R. (2006) Role of melanotransferrin in iron metabolism: studies using targeted gene disruption in vivo. Blood. 107(7):2599-601. IF 2006: 10.4 *Selected by the Editors of Blood as a Plenary Paper which this journal describes as “papers of exceptional scientific importance”. 2. Dunn, L.L., Sekyere, E.O., Suryo Rahmanto, Y., and Richardson, D.R. (2006) The function of melanotransferrin: a role in melanoma cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 27(11):2157-69. IF 2006: 5.3 54 3.1. Introduction Melanotransferrin or melanoma tumour antigen p97 is an iron (Fe)-binding transferrin (Tf) homologue originally identified at high levels in melanomas and other tumours, cell lines and foetal tissues [Brown et al. 1981a; Brown et al. 1982; Woodbury et al. 1980]. Initial studies found MTf to be absent or only slightly expressed in normal adult tissues [Brown et al. 1981a], while later investigations demonstrated MTf in a range of normal tissues [Alemany et al. 1993; Rothenberger et al. 1996; Sciot et al. 1989]. Recent studies showed MTf to be expressed at higher levels in the brain and epithelial surfaces of the salivary gland, pancreas, testis, kidney and sweat gland ducts compared with other normal tissues [Richardson 2000; Sekyere et al. 2005; Sekyere et al. -

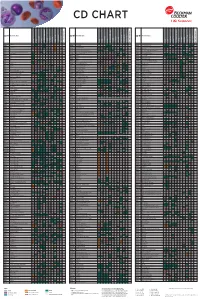

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Investigation of the Underlying Hub Genes and Molexular Pathogensis in Gastric Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatic Analyses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Investigation of the underlying hub genes and molexular pathogensis in gastric cancer by integrated bioinformatic analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The high mortality rate of gastric cancer (GC) is in part due to the absence of initial disclosure of its biomarkers. The recognition of important genes associated in GC is therefore recommended to advance clinical prognosis, diagnosis and and treatment outcomes. The current investigation used the microarray dataset GSE113255 RNA seq data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database to diagnose differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pathway and gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed, and a proteinprotein interaction network, modules, target genes - miRNA regulatory network and target genes - TF regulatory network were constructed and analyzed. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed. The 1008 DEGs identified consisted of 505 up regulated genes and 503 down regulated genes. -

Identification of Key Genes of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma by Integrated

Identication of key genes of papillary thyroid carcinoma by integrated bioinformatics analysis Gang Xue Hebei North University Xu Lin Hebei North University Jingfang Wu ( [email protected] ) Da Pei Hebei North University Dong-Mei Wang Hebei North University Jing Zhang Hebei North University Wen-Jing Zhang Hebei North University Research article Keywords: RNA-Seq, papillary thyroid carcinoma, key gene, bioinformatics Posted Date: January 7th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.20264/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/22 Abstract Background:Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is one of the fastest-growing malignant tumor types of thyroid cancer. Therefore, identifying the interaction of genes in PTC is crucial for elucidating its pathogenesis and nding more specic molecular biomarkers. Methods:In this study, 4 pairs of PTC tissues and adjacent tissues were sequenced using RNA-Seq, and 3745 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened. The results of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis indicate that the vast majority of DEGs may play a positive role in the development of cancer. Then, the signicant modules were analysed using Cytoscape software in the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network. Survival analysis, TNM analysis, and immune inltration analysis of key genes are all analyzed. And the expression of ADORA1, APOE and LPAR5 genes was veried by qPCR in papillary thyroid carcinoma compared to their matching adjacent tissues. Results: A total of 25 genes were identied as hub genes with nodes greater than 10. The expression of 25 key genes in PTC were veried by the GEPIA database, and the overall survival and disease free survival analyses of these key genes were conducted with Kaplan–Meier plots. -

Potent Cytotoxicity of an Auristatin-Containing Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting Melanoma Cells Expressing Melanotransferrin/P97

1474 Potent cytotoxicity of an auristatin-containing antibody-drug conjugate targeting melanoma cells expressing melanotransferrin/p97 Leia M. Smith, Albina Nesterova, Stephen C. Alley, with normal tissue, in conjunction with the greater Michael Y. Torgov, and Paul J. Carter sensitivity of tumor cells to L49-vcMMAF, supports further evaluation of antibody-drug conjugates for target- Seattle Genetics, Inc., Bothell, Washington ing p97-overexpressing tumors. [Mol Cancer Ther 2006;5(6):1474–82] Abstract Identifying factors that determine the sensitivity or Introduction f resistance of cancer cells to cytotoxicity by antibody-drug Malignant melanoma is responsible for 79% of deaths f conjugates is essential in the development of such from skin cancer ( 7,900 deaths estimated in the United conjugates for therapy. Here the monoclonal antibody States in 2006; ref. 1). Surgery is often curative for early L49 is used to target melanotransferrin, a glycosylphos- stage melanoma but is not a treatment option for disease phatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein first identified that has metastasized to distant organs such as lung or as p97, a cell-surface marker in melanomas. L49 was brain. Available treatments are limited to use of immuno- a conjugated via a proteolytically cleavable valine-citrulline therapy ( -IFN or interleukin-2) with or without combina- linker to the antimitotic drug, monomethylauristatin F tion chemotherapy drugs to delay recurrence of disease. (vcMMAF). Effective drug release from L49-vcMMAF Chemotherapy and radiation therapy for stage IV melano- likely requires cellular proteases most commonly located ma patients are not curative but mostly used to relieve in endosomes and lysosomes. Melanoma cell lines with symptoms or extend the life of patients. -

MALE Protein Name Accession Number Molecular Weight CP1 CP2 H1 H2 PDAC1 PDAC2 CP Mean H Mean PDAC Mean T-Test PDAC Vs. H T-Test

MALE t-test t-test Accession Molecular H PDAC PDAC vs. PDAC vs. Protein Name Number Weight CP1 CP2 H1 H2 PDAC1 PDAC2 CP Mean Mean Mean H CP PDAC/H PDAC/CP - 22 kDa protein IPI00219910 22 kDa 7 5 4 8 1 0 6 6 1 0.1126 0.0456 0.1 0.1 - Cold agglutinin FS-1 L-chain (Fragment) IPI00827773 12 kDa 32 39 34 26 53 57 36 30 55 0.0309 0.0388 1.8 1.5 - HRV Fab 027-VL (Fragment) IPI00827643 12 kDa 4 6 0 0 0 0 5 0 0 - 0.0574 - 0.0 - REV25-2 (Fragment) IPI00816794 15 kDa 8 12 5 7 8 9 10 6 8 0.2225 0.3844 1.3 0.8 A1BG Alpha-1B-glycoprotein precursor IPI00022895 54 kDa 115 109 106 112 111 100 112 109 105 0.6497 0.4138 1.0 0.9 A2M Alpha-2-macroglobulin precursor IPI00478003 163 kDa 62 63 86 72 14 18 63 79 16 0.0120 0.0019 0.2 0.3 ABCB1 Multidrug resistance protein 1 IPI00027481 141 kDa 41 46 23 26 52 64 43 25 58 0.0355 0.1660 2.4 1.3 ABHD14B Isoform 1 of Abhydrolase domain-containing proteinIPI00063827 14B 22 kDa 19 15 19 17 15 9 17 18 12 0.2502 0.3306 0.7 0.7 ABP1 Isoform 1 of Amiloride-sensitive amine oxidase [copper-containing]IPI00020982 precursor85 kDa 1 5 8 8 0 0 3 8 0 0.0001 0.2445 0.0 0.0 ACAN aggrecan isoform 2 precursor IPI00027377 250 kDa 38 30 17 28 34 24 34 22 29 0.4877 0.5109 1.3 0.8 ACE Isoform Somatic-1 of Angiotensin-converting enzyme, somaticIPI00437751 isoform precursor150 kDa 48 34 67 56 28 38 41 61 33 0.0600 0.4301 0.5 0.8 ACE2 Isoform 1 of Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 precursorIPI00465187 92 kDa 11 16 20 30 4 5 13 25 5 0.0557 0.0847 0.2 0.4 ACO1 Cytoplasmic aconitate hydratase IPI00008485 98 kDa 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 - 0.0081 - 0.0 -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

Dissection of the Process of Brain Metastasis Reveals Targets and Mechanisms for Molecular-Based Intervention ULRICH H

CANCER GENOMICS & PROTEOMICS 13 : 245-258 (2016) Review Dissection of the Process of Brain Metastasis Reveals Targets and Mechanisms for Molecular-based Intervention ULRICH H. WEIDLE 1, FABIAN BIRZELE 2, GWENDLYN KOLLMORGEN 1 and RÜDIGER RÜGER 1 1Roche Innovation Center Munich, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany; 2Roche Innovation Center, Basel, Switzerland Abstract. Brain metastases outnumber the incidence of brain of these patients is in the range of five weeks and can be tumors by a factor of ten. Patients with brain metastases have extended to 3-18 months by multi-modality therapy (4). a dismal prognosis and current treatment modalities achieve Several different types of tumors display a pronounced tropism only a modest clinical benefit. We discuss the process of brain of metastasis to the brain. The incidence varies with the source metastasis with respect to mechanisms and involved targets to of information and ranges between 40-50% for lung cancer, 20- outline options for therapeutic intervention and focus on 30% for breast cancer, 20-25% for melanoma, 10-20% for breast and lung cancer, as well as melanoma. We describe the renal carcinoma and 4-6% for gastrointestinal tumors (5-8). process of penetration of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) by Different compartments and microenvironments of the brain disseminated tumor cells, establishment of a metastatic niche, can be colonized. For example, in patients with malignant colonization and outgrowth in the brain parenchyma. melanoma, 49% of the metastases are of intraparenchymal, Furthermore, the role of angiogenesis in colonization of the 22% of leptomingeal and 29% of dural location (9). In this brain parenchyma, interactions of extravasated tumor cells review, we focus on parenchymal brain metastases originating with microglia and astrocytes, as well as their propensity for from the tumor types as described above. -

Broad and Thematic Remodeling of the Surfaceome and Glycoproteome on Isogenic Cells Transformed with Driving Proliferative Oncogenes

Broad and thematic remodeling of the surfaceome and glycoproteome on isogenic cells transformed with driving proliferative oncogenes Kevin K. Leunga,1 , Gary M. Wilsonb,c,1, Lisa L. Kirkemoa, Nicholas M. Rileyb,c,d , Joshua J. Coonb,c, and James A. Wellsa,2 aDepartment of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143; bDepartment of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706; cDepartment of Biomolecular Chemistry, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706; and dDepartment of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 Edited by Benjamin F. Cravatt, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 24, 2020 (received for review October 14, 2019) The cell surface proteome, the surfaceome, is the interface for tumors. For example, lung cancer patients with oncogenic EGFR engaging the extracellular space in normal and cancer cells. Here mutations seldom harbor oncogenic KRAS or BRAF mutations we apply quantitative proteomics of N-linked glycoproteins to and vice versa (9). Also, recent evidence shows that oncogene reveal how a collection of some 700 surface proteins is dra- coexpression can induce synthetic lethality or oncogene-induced matically remodeled in an isogenic breast epithelial cell line senescence, further reinforcing that activation of one oncogene stably expressing any of six of the most prominent prolifera- without the others is preferable in cancer (10, 11). tive oncogenes, including the receptor tyrosine kinases, EGFR There is also substantial