Peptide-Based Strategies for Targeted Tumor Treatment and Imaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Unique Structure at the Carboxyl Terminus of the Largest Subunit of Eukaryotic RNA Polymerase II (Transcription/Gene Expression/Protein Phosphorylation) JEFFRY L

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 82, pp. 7934-7938, December 1985 Biochemistry A unique structure at the carboxyl terminus of the largest subunit of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II (transcription/gene expression/protein phosphorylation) JEFFRY L. CORDEN*, DEBORAH L. CADENAt, JOSEPH M. AHEARN, JR.*, AND MICHAEL E. DAHMUSt *Howard Hughes Medical Institute Laboratory, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205; and tDepartment of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of California, Davis, CA 95616 Communicated by Daniel Nathans, August 2, 1985 ABSTRACT Purified eukaryotic nuclear RNA polymerase alous mobility in NaDodSO4 gels due to postsynthetic mod- II consists of three subspecies that differ in the apparent ification cannot be ruled out. The three forms of the largest molecular masses of their largest subunit, designated Ho, Ha, subunit Ho (240 kDa), Iha (210-220 kDa), and lIb (170-180 and HIb for polymerase species HO, HA, and BIB, respectively. kDa) also differ in their ability to be phosphorylated both in Subunits Ho, Ha, and IHb are the products of a single gene. We vitro and in vivo (14). Subunit lIc (140 kDa) is structurally present here the amino acid composition of calf thymus different from IHo, Iha, and IIb (2, 33) and is present in all subunits Ha and lIb and the C-terminal amino acid sequence three forms of RNA polymerase II in equimolar stoichiom- of subunit Ha (Ho) inferred from the nucleotide sequence of etry with the largest subunit. part of the mouse gene encoding this RNA polymerase subunit. A monoclonal antibody prepared against calfthymus RNA The calculated amino acid composition ofthe peptide unique to polymerase II has been shown to recognize a determinant on subunit Ha indicates that subunit Ha contains a domain rich in subunit Iha (IIo) but not on IIb (15). -

Binding and Uptake of H-Ferritin Are Mediated by Human Transferrin Receptor-1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Caltech Authors Binding and uptake of H-ferritin are mediated by human transferrin receptor-1 Li Lia, Celia J. Fanga,b, James C. Ryana,b, Eréne C. Niemib, José A. Lebrónc,1, Pamela J. Björkmanc,d,2, Hisashi Arasee, Frank M. Tortif, Suzy V. Tortig, Mary C. Nakamuraa,b, and William E. Seamana,b,h,2 aDepartment of Medicine, Veterans Administration Medical Center, San Francisco, CA 94121; bDepartment of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143; cDivision of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125; dHoward Hughes Medical Institute, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125; eDepartment of Immunochemistry, World Premier International Immunology Frontier Research Center and Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan; fDepartment of Cancer Biology, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157; gDepartment of Biochemistry, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157; and hDepartment of Microbiology and Immunology, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143 Contributed by Pamela J. Björkman, November 18, 2009 (sent for review October 5, 2009) − Ferritin is a spherical molecule composed of 24 subunits of two constant of ∼6.5 × 10 7 L/mol and ∼10,000 receptors sites per cell; types, ferritin H chain (FHC) and ferritin L chain (FLC). Ferritin stores subsequently, they endocytose HFt (13). Activated fresh lympho- iron within cells, but it also circulates and binds specifically and cytes also bind HFt (16), as do erythroid precursors, in which the saturably to a variety of cell types. -

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

High Efficiency Blood-Brain Barrier Transport Using a VNAR Targeting the Transferrin Receptor 1 (Tfr1)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/816900; this version posted October 30, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title: High efficiency blood-brain barrier transport using a VNAR targeting the Transferrin Receptor 1 (TfR1) Authors: Pawel Stocki§, Jaroslaw M Szary§, Charlotte LM Jacobsen¶, Mykhaylo Demydchuk§, Leandra Northall§, Torben Moos¶, Frank S Walsh§ and J Lynn Rutkowski§* §Ossianix, Inc, Stevenage Bioscience Catalyst, Gunnels Wood Rd, Stevenage, Herts, SG1 2FX, UK and 3675 Market St, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA ¶Laboratory of Neurobiology, Department of Health Science and Technology, Aalborg University, Fredrik Bajers Vej 3, 9220 Aalborg, Denmark Address correspondence to: *J. Lynn Rutkowski, PhD Ossianix, Inc, 3675 Market St., Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: +1(610)291-1724 A one-sentence summary: Development of highly efficient, TfR1 specific, cross-species reactive blood-brain barrier (BBB) shuttle based on shark single domain VNAR antibody. Definitions of all symbols, abbreviations, and acronyms: Transferrin Receptor 1 (TfR1), blood-brain barrier (BBB), Transferrin (Tf), central nervous system (CNS), Variable domain of New Antigen Receptors (VNAR), complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3), room temperature (RT), size exclusion chromatography (SEC), human serum albumin (HSA), Neurotensin (NT), Immunohistochemistry (IHC), next generation sequencing (NGS), Pharmacokinetic (PK), blood-CSF barrier (BCSFB), Percentage injected dose (%ID), Area under the curve (AUC), attenuated effector function (AEF), sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS- PAGE), Western blot (WB), intravenous (IV) 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/816900; this version posted October 30, 2019. -

Mitochondrial Iron Metabolism and Its Role in Neurodegeneration

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 20 (2010) S551–S568 S551 DOI 10.3233/JAD-2010-100354 IOS Press Review Mitochondrial Iron Metabolism and Its Role in Neurodegeneration Maxx P. Horowitza,b,c and J. Timothy Greenamyreb,c,d,∗ aMedical Scientist Training Program, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA bCenter for Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA cDepartment of Neurology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA dPittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Accepted 16 April 2010 Abstract. In addition to their well-established role in providing the cell with ATP, mitochondria are the source of iron-sulfur clusters (ISCs) and heme – prosthetic groups that are utilized by proteins throughout the cell in various critical processes. The post-transcriptional system that mammalian cells use to regulate intracellular iron homeostasis depends, in part, upon the synthesis of ISCs in mitochondria. Thus, proper mitochondrial function is crucial to cellular iron homeostasis. Many neurodegenerative diseases are marked by mitochondrial impairment, brain iron accumulation, and oxidative stress – pathologies that are inter- related. This review discusses the physiological role that mitochondria play in cellular iron homeostasis and, in so doing, attempts to clarify how mitochondrial dysfunction may initiate and/or contribute to iron dysregulation in the context of neurodegenerative disease. We review what is currently known about the entry of iron into mitochondria, the ways in which iron is utilized therein, and how mitochondria are integrated into the system of iron homeostasis in mammalian cells. Lastly, we turn to recent advances in our understanding of iron dysregulation in two neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease), and discuss the use of iron chelation as a potential therapeutic approach to neurodegenerative disease. -

Propranolol-Mediated Attenuation of MMP-9 Excretion in Infants with Hemangiomas

Supplementary Online Content Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol-mediated attenuation of MMP-9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4773 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics Protein Name Prop 12 mo/4 Pred 12 mo/4 Δ Prop to Pred mo mo Myeloperoxidase OS=Homo sapiens GN=MPO 26.00 143.00 ‐117.00 Lactotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=LTF 114.00 205.50 ‐91.50 Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MMP9 5.00 36.00 ‐31.00 Neutrophil elastase OS=Homo sapiens GN=ELANE 24.00 48.00 ‐24.00 Bleomycin hydrolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=BLMH 3.00 25.00 ‐22.00 CAP7_HUMAN Azurocidin OS=Homo sapiens GN=AZU1 PE=1 SV=3 4.00 26.00 ‐22.00 S10A8_HUMAN Protein S100‐A8 OS=Homo sapiens GN=S100A8 PE=1 14.67 30.50 ‐15.83 SV=1 IL1F9_HUMAN Interleukin‐1 family member 9 OS=Homo sapiens 1.00 15.00 ‐14.00 GN=IL1F9 PE=1 SV=1 MUC5B_HUMAN Mucin‐5B OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC5B PE=1 SV=3 2.00 14.00 ‐12.00 MUC4_HUMAN Mucin‐4 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC4 PE=1 SV=3 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 HRG_HUMAN Histidine‐rich glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=HRG 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 PE=1 SV=1 TKT_HUMAN Transketolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TKT PE=1 SV=3 17.00 28.00 ‐11.00 CATG_HUMAN Cathepsin G OS=Homo -

Broad and Thematic Remodeling of the Surface Glycoproteome on Isogenic

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/808139; this version posted October 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Broad and thematic remodeling of the surface glycoproteome on isogenic cells transformed with driving proliferative oncogenes Kevin K. Leung1,5, Gary M. Wilson2,5, Lisa L. Kirkemo1, Nicholas M. Riley2,4, Joshua J. Coon2,3, James A. Wells1* 1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA Departments of Chemistry2 and Biomolecular Chemistry3, University of Wisconsin- Madison, Madison, WI, 53706, USA 4Present address Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 94305, USA 5These authors contributed equally *To whom correspondence should be addressed bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/808139; this version posted October 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract: The cell surface proteome, the surfaceome, is the interface for engaging the extracellular space in normal and cancer cells. Here We apply quantitative proteomics of N-linked glycoproteins to reveal how a collection of some 700 surface proteins is dramatically remodeled in an isogenic breast epithelial cell line stably expressing any of six of the most prominent proliferative oncogenes, including the receptor tyrosine kinases, EGFR and HER2, and downstream signaling partners such as KRAS, BRAF, MEK and AKT. -

Chapter 3: Phenotypic Characterisation of Melanotransferin Knockout Mouse and Down-Regulation of Melanotransferrin in Melanoma Cells

CHAPTER 3: PHENOTYPIC CHARACTERISATION OF MELANOTRANSFERIN KNOCKOUT MOUSE AND DOWN-REGULATION OF MELANOTRANSFERRIN IN MELANOMA CELLS “An ignorant person is one who doesn't know what you have just found out.” Will Rogers, 1879 - 1935 This Chapter is published in: 1. Sekyere, E.O., Dunn, L.L., Suryo Rahmanto, Y., and Richardson, D.R. (2006) Role of melanotransferrin in iron metabolism: studies using targeted gene disruption in vivo. Blood. 107(7):2599-601. IF 2006: 10.4 *Selected by the Editors of Blood as a Plenary Paper which this journal describes as “papers of exceptional scientific importance”. 2. Dunn, L.L., Sekyere, E.O., Suryo Rahmanto, Y., and Richardson, D.R. (2006) The function of melanotransferrin: a role in melanoma cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 27(11):2157-69. IF 2006: 5.3 54 3.1. Introduction Melanotransferrin or melanoma tumour antigen p97 is an iron (Fe)-binding transferrin (Tf) homologue originally identified at high levels in melanomas and other tumours, cell lines and foetal tissues [Brown et al. 1981a; Brown et al. 1982; Woodbury et al. 1980]. Initial studies found MTf to be absent or only slightly expressed in normal adult tissues [Brown et al. 1981a], while later investigations demonstrated MTf in a range of normal tissues [Alemany et al. 1993; Rothenberger et al. 1996; Sciot et al. 1989]. Recent studies showed MTf to be expressed at higher levels in the brain and epithelial surfaces of the salivary gland, pancreas, testis, kidney and sweat gland ducts compared with other normal tissues [Richardson 2000; Sekyere et al. 2005; Sekyere et al. -

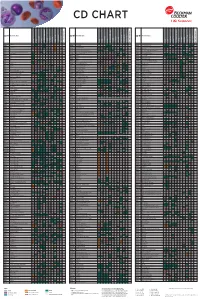

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Lysis of Red Blood Cells and Alveolar Epithelial Toxicity by Therapeutic Pulmonary Surfactants

0031-3998/95/3701-0026$03.0010 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 37, No. 1, 1995 Copyright 0 1994 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. Lysis of Red Blood Cells and Alveolar Epithelial Toxicity by Therapeutic Pulmonary Surfactants RICHARD D. FINDLAY, H. WILLIAM TAEUSCH, REMEDIOS DAVID-CU, AND FRANS J. WALTHER Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Martin Luther King, Jr./Drew University Medical Center, UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, Calijornia 90059 The risk of pulmonary hemorrhage is increased in extremely rats were treated with Survanta, Exosurf, the Exosurf compo- low birth weight infants treated with surfactant. The pathogenesis nents tyloxapol and hexadecanol, melittin, or culture medium of this increased risk is far from clear. We tested whether alone. After 24 h of incubation, lactate dehydrogenase release exposure of cell membranes to surfactant may lead to increased into the media was measured as a percent of total lactate dehy- membrane permeability, hypothesizing that this process may drogenase activity to indicate cytotoxicity. Lactate dehydroge- contribute to the occurrence of alveolar hemorrhage after surfac- nase release was <lo% for control experiments but increased tant treatment. Aliquots of washed packed red blood cells (used sharply with Exosurf and its components tyloxapol and hexade- as membrane model) were suspended in 0.9% NaCl with various canol. These results indicate that surfactant may be associated concentrations of Survanta or Exosurf for either 2 or 24 h at with in vitro cytotoxicity and that this property differs for dif- 37°C. Cytolysis was measured by spectrophotometric determi- ferent surfactants and different dosages. (Pediatr Res 37: 26-30, nation of free Hb after centrifugation. -

Investigation of the Underlying Hub Genes and Molexular Pathogensis in Gastric Cancer by Integrated Bioinformatic Analyses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Investigation of the underlying hub genes and molexular pathogensis in gastric cancer by integrated bioinformatic analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.20.423656; this version posted December 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The high mortality rate of gastric cancer (GC) is in part due to the absence of initial disclosure of its biomarkers. The recognition of important genes associated in GC is therefore recommended to advance clinical prognosis, diagnosis and and treatment outcomes. The current investigation used the microarray dataset GSE113255 RNA seq data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database to diagnose differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Pathway and gene ontology enrichment analyses were performed, and a proteinprotein interaction network, modules, target genes - miRNA regulatory network and target genes - TF regulatory network were constructed and analyzed. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed. The 1008 DEGs identified consisted of 505 up regulated genes and 503 down regulated genes. -

The Crosstalk: Exosomes and Lipid Metabolism

Wang et al. Cell Communication and Signaling (2020) 18:119 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-020-00581-2 REVIEW Open Access The crosstalk: exosomes and lipid metabolism Wei Wang1,2†, Neng Zhu3†, Tao Yan1,2†, Ya-Ning Shi1,2, Jing Chen4, Chan-Juan Zhang1,2, Xue-Jiao Xie5, Duan-Fang Liao1,2* and Li Qin1,2* Abstract Exosomes have been considered as novel and potent vehicles of intercellular communication, instead of “cell dust”. Exosomes are consistent with anucleate cells, and organelles with lipid bilayer consisting of the proteins and abundant lipid, enhancing their “rigidity” and “flexibility”. Neighboring cells or distant cells are capable of exchanging genetic or metabolic information via exosomes binding to recipient cell and releasing bioactive molecules, such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Of note, exosomes exert the remarkable effects on lipid metabolism, including the synthesis, transportation and degradation of the lipid. The disorder of lipid metabolism mediated by exosomes leads to the occurrence and progression of diseases, such as atherosclerosis, cancer, non- alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), obesity and Alzheimer’s diseases and so on. More importantly, lipid metabolism can also affect the production and secretion of exosomes, as well as interactions with the recipient cells. Therefore, exosomes may be applied as effective targets for diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Keywords: Exosome, Lipid metabolism, Atherosclerosis, Cancer Background the membrane [8]. Similar to the cell membrane, the lipid Exosomes display cup-like shape of 30 ~ 100 nm in diam- bilayer protects exosome contents from various stimuli in eter, and are secreted by multi-type cells, such as nerve thecirculatingfluid.Therefore,somecontentsinexo- cells [1], natural killer cells [2, 3], cancer cells [4, 5]and somes are usually transported remotely in circulating body adipocytes [6].