Corruption in Serbia: BRIBERY AS EXPERIENCED by the POPULATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AFTERMATH of YUGOSLAV WARS: the BIRTH of ORGANIZED CRIME Bachelor’S Thesis Programme of International Relations

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY School of Business and Governance Department of Law Tatu Rajala THE AFTERMATH OF YUGOSLAV WARS: THE BIRTH OF ORGANIZED CRIME Bachelor’s thesis Programme of International Relations Supervisor: Holger Mölder, PhD Tallinn 2019 I hereby declare that I have compiled the paper independently and all works, important standpoints and data by other authors has been properly referenced and the same paper has not been previously presented for grading. The document length is 7663 words from the introduction to the end of conclusion. Tatu Rajala …………………………… (signature, date) Student code: 156098TASB Student e-mail address: [email protected] Supervisor: Holder Mölder, PhD: The paper conforms to requirements in force …………………………………………… (signature, date) Chairman of the Defence Committee: Permitted to the defence ………………………………… (name, signature, date) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 5 1. THE EVOLUTION OF ORGANIZED CRIME IN WESTERN BALKANS ............................ 7 1.1. Forms of organized crime in the Western Balkans................................................................. 10 1.1.1. Corruption ........................................................................................................................ 10 1.1.2. Illegal smuggling and -

Medical Management of Biologic Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Fourth Edition February 2001 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES ¨ FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND 1 Sources of information: National Response Center 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Help line: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center - for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Center: 1-770-488-7100 John's Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense: 1-410-223-1667 (Civilian Biodefense Studies) An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version and a Palm OS Electronic version of this Handbook can both be downloaded from the Internet at: http://www.usamriid.army.mil/education/bluebook.html 2 USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Fourth Edition February 2001 Editors: LTC Mark Kortepeter LTC George Christopher COL Ted Cieslak CDR Randall Culpepper CDR Robert Darling MAJ Julie Pavlin LTC John Rowe COL Kelly McKee, Jr. COL Edward Eitzen, Jr. Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 3 PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. Since the first edition in 1993, the awareness of biological weapons in the United States has increased dramatically. -

Development Ofmonitoring Instruments Forjudicial and Law

Background Research on Systems and Context on Systems Research Background Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement institutions in the Western Balkans Background Research on Systems and Context Justice and Home Affairs Statistics in the Western Balkans 2009 - 2011 CARDS Regional Action Programme With funding by the European Commission April 2010 Disclaimers This Report has not been formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations and neither do they imply any endorsement. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Comments on this report are welcome and can be sent to: Statistics and Survey Section United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime PO Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria Tel: (+43) 1 26060 5475 Fax: (+43) 1 26060 7 5475 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org 1 Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement Institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Background Research on Systems and Context 2 Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement Institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Background Research on Systems and Context Justice and Home Affairs Statistics in the Western Balkans April 2010 3 Acknowledgements Funding for this report was provided by the European Commission under the CARDS 2006 Regional Action Programme. This report was produced under the responsibility of Statistics and Surveys Section (SASS) and Regional Programme Office for South Eastern Europe (RPOSEE) of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) based on research conducted by the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). -

BBC Public Complaints Responses 2016.Pdf

Archived BBC public responses to complaints 2016 BBC News, Coverage of the death of David Bowie, 12 January 2016 Complaint We received complaints from viewers and listeners who felt there was too much coverage of David Bowie’s death during BBC News programmes and bulletins. Response from BBC News David Bowie was by common consent one of our greatest pop stars who attracted a global following. He appealed across the ages and was one of the most influential musicians of his time. His death was both sudden and unexpected, his illness not revealed to anyone but a tight circle of friends. Our coverage tried to reflect his stature as a musician whose capacity for invention changed the shape of the industry, and the shock at his death around the world. Question Time, BBC One, 14 January 2016 Complaint We received complaints from viewers who felt the panel had a right wing bias. Response from Question Time Over the course of a series Question Time aims to achieve balance and hear from a range of voices. Each programme usually consists of one senior politician from both the Labour and Conservative party, as well as representatives from other political parties. The rest of the panel is made of political commentators, journalists, and other public figures that add a different perspective and represent a range of viewpoints across the series. We also aim to ensure that each episode has a divergent and broad range of views from the panel on the likely topics that our audience wish to raise. David Dimbleby moderates the debate to ensure panellists are given the opportunity to make their views known in a fair way. -

Americans and Russians Are Mostly Disinterested and Disengaged with Each Other

Americans and Russians Are Mostly Disinterested and Disengaged with Each Other Brendan Helm, Research Assistant, Public Opinion, Chicago Council on Global Affairs Arik Burakovsky, Assistant Director, Russia and Eurasia Program, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University Lily Wojtowicz, Research Associate, Public Opinion, Chicago Council on Global Affairs August 2019 The last few years have seen a substantial deterioration in relations between the United States and Russia. The international crisis over Ukraine, Russia’s interference in the 2016 US presidential election, and US sanctions against Russia have all contributed to the growing acrimony. Recent surveys conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the Levada Analytical Center reveal that large majorities of both Russians and Americans now view their countries as rivals. But in the midst of heightened tensions between Moscow and Washington, how do regular citizens of each country view one another? A joint project conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, the Levada Analytical Center, and The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University shows that despite the perception of rivalry between their countries, Russians’ and Americans’ views on the people of the other country are more favorable. However, the survey results also show that Russians and Americans are not particularly curious about each other, they rarely follow news about one another, and the majority of each group has never met someone from the other. Nonetheless, self-reported interests from each side in arts and sciences suggest that there are non-political paths toward warmer relations. Key Findings • 68 percent of Americans view Russians either very or fairly positively, while 48 percent of Russians have those views of Americans. -

John Lewis' 'Good Trouble' Handbook

“THE RIGHT TO VOTE IS THE MOST POWERFUL NONVIOLENT TOOL WE HAVE IN A DEMOCRACY. I RISKED MY LIFE DEFENDING THAT RIGHT.” – Congressman John Lewis, John Lewis: Good Trouble Go to Map GOOD TROUBLE Congressman John Lewis’ life’s work has changed the very fabric of this country. Born in During the protest, John Lewis was hit on the head by a state trooper and suffered a the heart of the Jim Crow South, in the shadow of slavery, he saw the profound injustice fractured skull. On Bloody Sunday, Lewis risked his life for the right to vote and has since all around him and knew, from a young age, that he wanted to do something about it. By devoted his life to ensuring that every American has access to the ballot box. his late teens, he had joined the first Freedom Riders and later became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the groups responsible Unfortunately, Congressman Lewis’ work did not end with the Civil Rights era. In 2013, for organizing the 1963 March on Washington. On August 28, 1963, on the steps of the Voting Rights Act, for which he shed his blood, was effectively gutted by a Supreme the Lincoln Memorial, John Lewis gave his own rousing speech alongside some of the Court decision, Shelby County v. Holder. In the years since, voter suppression targeting greatest leaders of the civil rights movement, including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. communities of color has significantly increased. But it was March 7, 1965, that etched Congressman Lewis into the American psyche. -

Circle of Scholars

Circle of Scholars 2021 Spring Online Circle Courses of Scholars Salve Regina University’s Circle of Scholars is a lifelong learning program for adults of all inclinations Online Seminar Catalog and avocations. We enlighten, challenge, and entertain. The student-instructor relationship is one of mutual respect and offers vibrant discussion on even the most controversial of global and national issues. We learn from each other with thoughtful, receptive minds. 360 degrees. Welcome to Salve Regina and enjoy the 2020 selection of fall seminars. Online registration begins on Wednesday, February 3, 2021 at noon www.salve.edu/circleofscholars Seminars are filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Please register online using your six-digit Circle of Scholars identification number (COSID). As in the past, you will receive confirmation of your credit card payment when you complete the registration process. For each seminar you register for, you will receive a Zoom email invitation to join the seminar 1-3 days before the start date. If you need assistance or have questions, please contact our office at (401) 341-2120 or email [email protected]. Important Program Adjustments for Spring 2021 • Most online seminars will offer 1.5 hour sessions. • Online class fees begin at $15 for one session and range to $85 for 8 sessions. • The 2019-2020 annual membership was extended from July 2019 - December 2020 due to COVID- 19. Membership renewal is for • Zoom is our online platform. If you do not have a Zoom account already, please visit the Zoom website to establish a free account at https://zoom.us. -

BTI 2018 Country Report — Serbia

BTI 2018 Country Report Serbia This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Serbia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Serbia 3 Key Indicators Population M 7.1 HDI 0.776 GDP p.c., PPP $ 14512 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.5 HDI rank of 188 66 Gini Index 29.1 Life expectancy years 75.5 UN Education Index 0.779 Poverty3 % 1.4 Urban population % 55.7 Gender inequality2 0.185 Aid per capita $ 44.0 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Serbia’s current political system is characterized by the dominant rule of one political party at the national and provincial level, as well as most of the local government units. -

Research Conferences on Organised Crime at the Bundeskriminalamt In

Corruption and Organised Crime Threats in Southern Eastern Europe Ugljesa Zvekic Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime 1 Organised Crime and Corruption in the Global Developmental Perspective In this article the emphasis was on a nearly inherent link between organised crime and corruption on a local as well as transnational level. Wherever there is ground prone to corruption, there is also a favourable ground for organised crime; and vice versa. Much of the prone ground for organised corruption is established through firstly a low corruption level which then accelerates to a more sophisticated level of corruption, in particular when linked to organised crime. Furthermore, it was professed that today more intricate activities in or- ganised crime can be linked to more intricate activities in corruption, making them mutually instrumental. Historically speaking, two contradictory trends were identified: Firstly a de- cline in violent crimes over the past century and decades, and secondly an in- crease in global organised crime and corruption, which in turn promoted more international legal responses and cooperation. (Pinker, Mack 2014/ 2015) The phenomenon of organised crime is not new to the global crime trends but the scale and scope have shifted vigorously. Change is also pre- sents in new forms and methods of legitimizing illicitly gained profit. The im- pact comes to light in the form of shifts in major illicit markets, an expansion of new criminal markets as well as a blurring of traditional producer, consu- mer and transit state typologies. Therefore, organised crime and corruption both have broader implications than defined within the traditional security and justice framework; hence they are now recognised as cross-cutting threats to a sustainable development which is also pictured by the 16th goal of the Sustainable Development Goals1. -

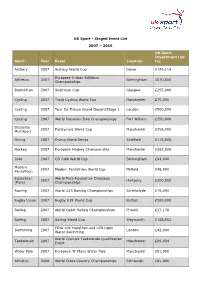

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

2021 Fina Clinics for Coaches & Officials

2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines 1 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines INDEX Introduction How to host/register • Overview 3 • How to host a FINA Clinic 9 • Objective 3 • How to register in a FINA Clinic 9 Clinic description and format Clinic organisation • Description 4 • Clinic details 10 • Course format 4 • Material or artwork produced 10 • Clinic location 5 • Teaching modalities 5 Financial conditions • Clinic content 5 • Regulations for FINA Clinics 11 • Certificates 7 • Economical support 11 • Clinic fees 7 • FINA Online Clinic 13 Bidding procedure • Reimbursement procedure 14 • Invoicing guidelines 14 • Application procedure 8 • Analysis and approval 8 2 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES & OFFICIALS Guidelines 2021 FINA CLINICS FOR COACHES AND OFFICIALS Introduction Overview FINA strongly believes in the importance of having a globally-respected workforce of coaches and swimming officials with an established and consistent curriculum, as a key factor for the athlete development and the correct appliance of the FINA officiating rules. As part of the FINA Development Programme, FINA is currently running clinics to train coaches in each of the six aquatic disciplines: swimming, open water swimming, artistic swimming, water polo, diving and high diving and to train officials in swimming. Both training programmes, respectively conducted by highly experienced coaches and officials appointed by FINA, are designed to educate and train coaches and swimming officials around the world. With this initiative, FINA offers to its 209 affiliated national federations the opportunity to successfully develop the aquatic sports in their countries. Objective The FINA Clinics for Coaches and FINA Swimming Clinics for Officials are intended to provide basic training for participants of all levels through courses led by an expert nominated by FINA. -

Corruption in Serbia: [email protected]

U4 Helpdesk Answer U4 Helpdesk Answer 2020 17 April 2020 AUTHOR Overview of corruption and Nieves Zúñiga (TI) anti-corruption in Serbia: [email protected] Changes in the last 10 years REVIEWED BY Guillaume Nicaise (U4) The evolution of corruption and anti-corruption in Serbia has [email protected] followed the transition from a fragile government led by the Democratic Party to an increasingly centralised and authoritarian Transparency Serbia regime led by the Serbian Progressive Party. Even if there is no [email protected] evidence of a significant change in the level of corruption, corruption in the Balkan country shapes political dynamics, resulting in the capture of political decision making and the political control of independent institutions, the judiciary and the legislature. The progress made in anti-corruption has been more RELATED U4 MATERIAL on paper than in practice, with the implementation of those Western Balkans and Turkey: reforms being the main challenge. Overview of Corruption and Anti- Corruption Corruption and doing business in Serbia Helpdesk Answers are tailor-made research briefings compiled in ten working days. The U4 Helpdesk is a free research service run in collaboration with Transparency International. Query How has corruption evolved in the past 10 years in Serbia? To what extent is corruption connected to political dynamics and social norms? Give an overview of anti-corruption initiatives in Serbia. Contents MAIN POINTS — In the last ten years there has not been a 1. Introduction significant change in the level of corruption 2. Evolution of corruption in the last 10 years in Serbia. a. Extent of corruption b.