Cannibalizing Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

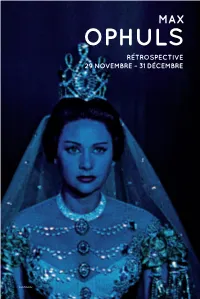

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

David Hare's the Blue Room and Stanley

Schnitzler as a Space of Central European Cultural Identity: David Hare’s The Blue Room and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut SUSAN INGRAM e status of Arthur Schnitzler’s works as representative of fin de siècle Vien- nese culture was already firmly established in the author’s own lifetime, as the tributes written in on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday demonstrate. Addressing Schnitzler directly, Hermann Bahr wrote: “As no other among us, your graceful touch captured the last fascination of the waning of Vi- enna, you were the doctor at its deathbed, you loved it more than anyone else among us because you already knew there was no more hope” (); Egon Friedell opined that Schnitzler had “created a kind of topography of the constitution of the Viennese soul around , on which one will later be able to more reliably, more precisely and more richly orient oneself than on the most obese cultural historian” (); and Stefan Zweig noted that: [T]he unforgettable characters, whom he created and whom one still could see daily on the streets, in the theaters, and in the salons of Vienna on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, even yesterday… have suddenly disappeared, have changed. … Everything that once was this turn-of-the-century Vienna, this Austria before its collapse, will at one point… only be properly seen through Arthur Schnitzler, will only be called by their proper name by drawing on his works. () With the passing of time, the scope of Schnitzler’s representativeness has broadened. In his introduction to the new English translation of Schnitzler’s Dream Story (), Frederic Raphael sees Schnitzler not only as a Viennese writer; rather “Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa” (xii). -

Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected]

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2012 Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Berry, Jeffrey Erik, "Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man" (2012). Honors Theses. 10. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/10 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Departments of History and of German & Russian Studies Bates College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Jeffrey Berry Lewiston, Maine 23 March 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisors, Professor Craig Decker from the Department of German and Russian Studies and Professor Jason Thompson of the History Department, for their patience, guidance and expertise during this extensive and rewarding process. I also would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to the people who will be participating in my defense, Professor John Cole of the Bates College History Department, Profesor Raluca Cernahoschi of the Bates College German Department, and Dr. Richard Blanke from the University of Maine at Orno History Department, for their involvement during the culminating moment of my thesis experience. Finally, I would like to thank all the other people who were indirectly involved during my research process for their support. -

Cannibalizing Cultures

1 DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Cannibalizing Cultures: Schnitzler in London, Stoppard in Vienna. The Influence of Socio-cultural, Literary, and Power-related Norms on Drama Translation” Verfasserin/ Verfasser Julia-Stefanie Maier, Bakk. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 347 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium UF Englisch UF Französisch Betreuerin/ Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ewald Mengel 2 3 To those who have showed me what intercultural awareness means. 4 5 Acknowledgements I am grateful to my advisor, Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ewald Mengel, for his constant guidance and support. His expertise in the field of translation studies and literary theory has been of invaluable help and has led to many interesting discussions. His encouragement and his belief in my project have given me the chance to do something new in my field of predilection, translation studies, within the realms of the research program Weltbühne Wien . It is an honor for me to have been invited to contribute to this project. Many thanks also go to Elisabeth, Heather, and Zandra for proofreading the paper. Last but not least, I would like to thank my parents and Vincent for their inexhaustible love and support. 6 7 Declaration of Authenticity I confirm to have conceived and written this paper in English all by myself. Quotations from other authors are all clearly marked and acknowledged in the bibliographical references within the text. Any ideas borrowed and/or passages paraphrased from the works of other authors are equally truthfully acknowledged and identified. Hinweis Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin oder der betreffende Kandidat befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. -

1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quinze, 34-35 | 2001 Le Voyage Immobile 2

1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 34-35 | 2001 Max Ophuls Le voyage immobile Philippe Roger Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/172 DOI : 10.4000/1895.172 ISBN : 978-2-8218-1032-7 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2001 Pagination : 85-98 ISBN : 2-913758-05-3 ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Philippe Roger, « Le voyage immobile », 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze [En ligne], 34-35 | 2001, mis en ligne le 23 janvier 2007, consulté le 28 septembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ 1895/172 ; DOI : 10.4000/1895.172 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 28 septembre 2019. © AFRHC Le voyage immobile 1 Le voyage immobile Philippe Roger 1 « La vie, pour moi, c’est le mouvement », confie Lola à Liszt. De ce mot entendu dans le dernier film d’Ophuls, nombre de commentateurs semblent avoir inféré que ce cinéma serait celui du mouvement. De fait, la caméra du grand Max est réputée pour son agilité ; sous son regard, personnages et objets bougent avec une constance indéniable. La cause paraît entendue, qui pourtant mérite enquête. L’apparence n’est-elle pas sujette à caution ? Le premier volet du Plaisir ne s’appelle pas « Le masque » sans raison ; de cette pièce saisissante, on cite toujours l’introduction enfiévrée, rutilante, oubliant ce qui suit et lui donne sens, la mansarde obscure où veille à pas comptés l’épouse du viveur. -

Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: a Struggle of German-Jewish Identities

University of Cambridge Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages Department of German and Dutch Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: A Struggle of German-Jewish Identities This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Max Matthias Walter Haberich Clare Hall Supervisor: Dr. David Midgley St. John’s College Easter Term 2013 Declaration of Originality I declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work. This thesis includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. Signed: June 2013 Statement of Length With a total count of 77.996 words, this dissertation does not exceed the word limit as set by the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages, University of Cambridge. Signed: June 2013 Summary of Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: A Struggle of German- Jewish Identities by Max Matthias Walter Haberich The purpose of this dissertation is to contrast the differing responses to early political anti- Semitism by Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann. By drawing on Schnitzler’s primary material, it becomes clear that he identified with certain characters in Der Weg ins Freie and Professor Bernhardi. Having established this, it is possible to trace the development of Schnitzler’s stance on the so-called ‘Jewish Question’: a concept one may term enlightened apolitical individualism. Enlightened for Schnitzler’s rejection of Jewish orthodoxy, apolitical because he always remained strongly averse to politics in general, and individualism because Schnitzler felt there was no general solution to the Jewish problem, only one for every individual. For him, this was mainly an ethical, not a political issue; and he defends his individualist position in Professor Bernhardi. -

The Museum of Modern Art Celebrates Vienna's Rich

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART CELEBRATES VIENNA’S RICH CINEMATIC HISTORY WITH MAJOR COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema Is Held in Conjunction with Carnegie Hall’s Citywide Festival Vienna: City of Dreams, and Features Guest Appearances by VALIE EXPORT and Jem Cohen Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema February 27–April 20, 2014 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 29, 2014—In honor of the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, The Museum of Modern Art presents a major collaborative exhibition exploring Vienna as a city both real and mythic throughout the history of cinema. With additional contributions from the Filmarchiv Austria, the exhibition focuses on Austrian and German Jewish émigrés—including Max Ophuls, Erich von Stroheim, and Billy Wilder—as they look back on the city they left behind, as well as an international array of contemporary filmmakers and artists, such as Jem Cohen, VALIE EXPORT, Michael Haneke, Kurt Kren, Stanley Kubrick, Richard Linklater, Nicholas Roeg, and Ulrich Seidl, whose visions of Vienna reveal the powerful hold the city continues to exert over our collective unconscious. Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema is organized by Alexander Horwath, Director, Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, and Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film, MoMA, with special thanks to the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. The exhibition is also held in conjunction with Vienna: City of Dreams, a citywide festival organized by Carnegie Hall. Spanning the late 19th to the early 21st centuries, from historical and romanticized images of the Austro-Hungarian empire to noir-tinged Cold War narratives, and from a breeding ground of anti- Semitism and European Fascism to a present-day center of artistic experimentation and socioeconomic stability, the exhibition features some 70 films. -

New Releases New Releases

January February We Own the Night La Vie de Bohème -S M T W T F S S M T W T F S New Releases New Releases 1:00pm 1:00pm 1:00pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 4:00pm 1:30pm Capernaum For more New Release Opens Jan 11 Jurassic Park Catch Me If You Can The Terminal Minority Report E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial The Iron Giant: Love Story STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG titles, visit tiff.net Signature Edition SPECIAL SCREENINGS 1999 Cold War 3:45pm 3:50pm 3:55pm 3:35pm 3:15pm 4:15pm Opens Jan 25 The Lost World: Super 8 The Color Purple Catch Me If You Can Schindler’s List 7:00pm Crime and Punishment The Image Book Jurassic Park STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG Shadows in Paradise AKI KAURISMÄKI STEVEN SPIELBERG AKI KAURISMÄKI Opens Jan 25 6:15pm 7:00pm 6:15pm 7:00pm 6:30pm 6:40pm Jaws Close Encounters The Yards In Conversation With... 9:00pm The Straight Story Raiders of the Lost Ark STEVEN SPIELBERG of the Third Kind with James Gray James Gray The 36th Chamber 1999 STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG JAMES GRAY JAMES GRAY For more New Release 9:15pm of Shaolin 9:00pm SHAW BROTHERS titles, visit tiff.net 9:20pm Minority Report 9:45pm 9:30pm 10:00pm Badlands Twister STEVEN SPIELBERG War of the Worlds James Gray Carte Blanche: Duel SPECIAL SCREENINGS STEVEN SPIELBERG STEVEN SPIELBERG Other Men’s Women STEVEN SPIELBERG JAMES GRAY 1 2 10:30am 6:30pm 6:45pm 6:25pm 1:00pm 1:00pm Secret Movie Club Hamlet Goes Business The Match Factory Girl I Hired a Contract Killer Love Story McCabe & Mrs. -

Cinematic Vitalism Film Theory and the Question of Life

INGA POLLMANN INGA FILM THEORY FILM THEORY IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY CINEMATIC VITALISM FILM THEORY AND THE QUESTION OF LIFE INGA POLLMANN CINEMATIC VITALISM Cinematic Vitalism: Film Theory and the INGA POLLMANN is Assistant Professor Question of Life argues that there are in Film Studies in the Department of Ger- constitutive links between early twen- manic and Slavic Languages and Litera- tieth-century German and French film tures at the University of North Carolina theory and practice, on the one hand, at Chapel Hill. and vitalist conceptions of life in biology and philosophy, on the other. By consi- dering classical film-theoretical texts and their filmic objects in the light of vitalist ideas percolating in scientific and philosophical texts of the time, Cine- matic Vitalism reveals the formation of a modernist, experimental and cinema- tic strand of vitalism in and around the movie theater. The book focuses on the key concepts rhythm, environment, mood, and development to show how the cinematic vitalism articulated by film theorists and filmmakers maps out connections among human beings, mi- lieus, and technologies that continue to structure our understanding of film. ISBN 978-94-629-8365-6 AUP.nl 9 789462 983656 AUP_FtMh_POLLMANN_(cinematicvitalism)_rug17.7mm_v02.indd 1 21-02-18 13:05 Cinematic Vitalism Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. Adopting a historical perspective, but with a firm eye to the further development of the field, the series provides a platform for ground-breaking new research into film theory and media history and features high-profile editorial projects that offer resources for teaching and scholarship. -

1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quinze, 34-35 | 2001 « Il Faut Écrire Comme on Se Souvient » : La Poétique De Max Ophuls 2

1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 34-35 | 2001 Max Ophuls « Il faut écrire comme on se souvient » : la poétique de Max Ophuls Barthélemy Amengual Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/165 DOI : 10.4000/1895.165 ISBN : 978-2-8218-1032-7 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2001 Pagination : 13-26 ISBN : 2-913758-05-3 ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Barthélemy Amengual, « « Il faut écrire comme on se souvient » : la poétique de Max Ophuls », 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze [En ligne], 34-35 | 2001, mis en ligne le 23 janvier 2007, consulté le 24 septembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/165 ; DOI : 10.4000/1895.165 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2019. © AFRHC « Il faut écrire comme on se souvient » : la poétique de Max Ophuls 1 « Il faut écrire comme on se souvient » : la poétique de Max Ophuls Barthélemy Amengual La grandeur de l’artiste tient à son pouvoir d’imaginer la vérité du réel. Goethe 1 Joseph Joubert note dans ses Carnets : « Il faut écrire non comme on sent mais comme on se souvient. » Joubert poserait-il une incompatibilité entre le sentiment, voire la sensation, et le souvenir ? Ce n’est pas ce que j’entends dans son aphorisme. J’y vois plutôt un double paradoxe : l’exigence d’une distance, d’un recul qui devrait conserver au souvenir sa vérité et, tout ensemble, le consentement à cet inévitable qui veut que toute mémoire soit trompeuse/trompée – subjective, comme on dit. -

Experiment in the Film

sh. eitedbyM&l MANVOX EXPERIMENT IN THE FILM edited by Roger Manveil In all walks of life experiment precedes and paves the way for practical and widespread development. The Film is no exception, yet although it must be considered one of the most popular forms of entertainment, very little is known by the general public about its experimental side. This book is a collec- tion of essays by the leading experts of all countries on the subject, and it is designed to give a picture of the growth and development of experiment in the Film. Dr. Roger Manvell, author of the Penguin book Film, has edited the collection and contributed a general appreciation. Jacket design by William Henry 15s. Od. net K 37417 NilesBlvd S532n 510-494-1411 Fremont CA 94536 www.nilesfilminiiseuin.org Scanned from the collections of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum Coordinated by the Media History Digital Library www.mediahistoryproject.org Funded by a donation from Jeff Joseph EDITED BY ROGER MANVELL THE GREY WALLS PRESS LTD First published in 1949 by the Grey Walls Press Limited 7 Crown Passage, Pall Mall, London S.W.I Printed in Great Britain by Balding & Mansell Limited London All rights reserved AUSTRALIA The Invincible Press Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide NEW ZEALAND The Invincible Press, Wellington SOUTH AFRICA M. Darling (Pty.) Ltd., Capetown EDITOR'S FOREWORD The aim of this book is quite simply to gather together the views of a number of people, prominent either in the field of film-making or film-criticism or in both, on the contribution of their country to the experimental development of the film.