Before Hollywood: Max Ophüls, Curtis Bernhardt, and Robert Siodmak in Exile in Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special

Princeton Garden Theatre Previews93G SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2015 Benedict Cumberbatch in rehearsal for HAMLET INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS P RINCETONG ARDENT HEATRE.ORG 609 279 1999 Welcome to the nonprofit Princeton Garden Theatre The Garden Theatre is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Our management team. ADMISSION Nonprofit Renew Theaters joined the Princeton community as the new operator of the Garden Theatre in July of 2014. We General ............................................................$11.00 also run three golden-age movie theaters in Pennsylvania – the Members ...........................................................$6.00 County Theater in Doylestown, the Ambler Theater in Ambler, and Seniors (62+) & University Staff .........................$9.00 the Hiway Theater in Jenkintown. We are committed to excellent Students . ..........................................................$8.00 programming and to meaningful community outreach. Matinees Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 How can you support Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$8.00 the Garden Theatre? PRINCETON GARDEN THEATRE Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$7.00 Be a member. MEMBER Affiliated Theater Members* .............................$6.00 Become a member of the non- MEMBER You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. profit Garden Theatre and show The above ticket prices are subject to change. your support for good films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a membership form or join online. Your financial support is tax-deductible. *Affiliated Theater Members Be a sponsor. All members of our theater are entitled to members tickets at all Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange “Renew Theaters” (Ambler, County, Garden, and Hiway), as well for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety as at participating “Art House Theaters” nationwide. -

A Foreign Affair (1948)

Chapter 3 IN THE RUINS OF BERLIN: A FOREIGN AFFAIR (1948) “We wondered where we should go now that the war was over. None of us—I mean the émigrés—really knew where we stood. Should we go home? Where was home?” —Billy Wilder1 Sightseeing in Berlin Early into A Foreign Affair, the delegates of the US Congress in Berlin on a fact-fi nding mission are treated to a tour of the city by Colonel Plummer (Millard Mitchell). In an open sedan, the Colonel takes them by landmarks such as the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, Pariser Platz, Unter den Lin- den, and the Tiergarten. While documentary footage of heavily damaged buildings rolls by in rear-projection, the Colonel explains to the visitors— and the viewers—what they are seeing, combining brief factual accounts with his own ironic commentary about the ruins. Thus, a pile of rubble is identifi ed as the Adlon Hotel, “just after the 8th Air Force checked in for the weekend, “ while the Reich’s Chancellery is labeled Hitler’s “duplex.” “As it turned out,” Plummer explains, “one part got to be a great big pad- ded cell, and the other a mortuary. Underneath it is a concrete basement. That’s where he married Eva Braun and that’s where they killed them- selves. A lot of people say it was the perfect honeymoon. And there’s the balcony where he promised that his Reich would last a thousand years— that’s the one that broke the bookies’ hearts.” On a narrative level, the sequence is marked by factual snippets infused with the snide remarks of victorious Army personnel, making the fi lm waver between an educational program, an overwrought history lesson, and a comedy of very dark humor. -

Katie Wackett Honours Final Draft to Publish (FILM).Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Female Subjectivity, Film Form, and Weimar Aesthetics: The Noir Films of Robert Siodmak by Kathleen Natasha Wackett A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BA HONOURS IN FILM STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA, AND FILM CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Kathleen Natasha Wackett 2017 Abstract This thesis concerns the way complex female perspectives are realized through the 1940s noir films of director Robert Siodmak, a factor that has been largely overseen in existing literature on his work. My thesis analyzes the presentation of female characters in Phantom Lady, The Spiral Staircase, and The Killers, reading them as a re-articulation of the Weimar New Woman through the vernacular of Hollywood cinema. These films provide a representation of female subjectivity that is intrinsically connected to film as a medium, as they deploy specific cinematic techniques and artistic influences to communicate a female viewpoint. I argue Siodmak’s iterations of German Expressionist aesthetics gives way to a feminized reading of this style, communicating the inner, subjective experience of a female character in a visual manner. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without my supervisor Dr. Lee Carruthers, whose boundless guidance and enthusiasm is not only the reason I love film noir but why I am in film studies in the first place. I’d like to extend this grateful appreciation to Dr. Charles Tepperman, for his generous co-supervision and assistance in finishing this thesis, and committee member Dr. Murray Leeder for taking the time to engage with my project. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

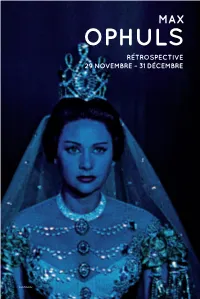

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951

The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951 by J. Greco ISBN: 1-58112-081-8 DISSERTATION.COM 1999 Copyright © 1999 Joseph Greco All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-58112-081-8 Dissertation.com USA • 1999 www.dissertation.com/library/1120818a.htm TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PRONOUNCED SEE-ODD-MACK ______________________ 4 CHAPTER ONE GETTING YOUR OWN WAY IN HOLLYWOOD __________ 7 CHAPTER TWO I NEVER PROMISE THEM A GOOD PICTURE ...ONLY A BETTER ONE THAN THEY EXPECTED ______ 25 CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY _____________________________ 25 THE SUSPECT _____________________________________ 49 THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY ___________ 59 THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE ___________________________ 74 THE KILLERS _____________________________________ 86 CRY OF THE CITY_________________________________ 100 CRISS CROSS _____________________________________ 116 THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON ___________________ 132 CHAPTER THREE HOLLYWOOD? A SORT OF ANARCHY _______________ 162 AFTERWORD THE FILE ON ROBERT SIODMAK___________________ 179 THE COMPLETE ROBERT SIODMAK FILMOGRAPHY_ 185 BIBLIOGRAPHY __________________________________ 214 iii INTRODUCTION PRONOUNCED SEE-ODD-MACK Making a film is a matter of cooperation. If you look at the final credits, which nobody reads except for insiders, then you are surprised to see how many colleagues you had who took care of all the details. Everyone says, ‘I made the film’ and doesn’t realize that in the case of a success all branches of film making contributed to it. The director, of course, has everything under control. —Robert Siodmak, November 1971 A book on Robert Siodmak needs an introduction. Although he worked ten years in Hollywood, 1941 to 1951, and made 23 movies, many of them widely popular thrillers and crime melo- dramas, which critics today regard as classics of film noir, his name never became etched into the collective consciousness. -

David Hare's the Blue Room and Stanley

Schnitzler as a Space of Central European Cultural Identity: David Hare’s The Blue Room and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut SUSAN INGRAM e status of Arthur Schnitzler’s works as representative of fin de siècle Vien- nese culture was already firmly established in the author’s own lifetime, as the tributes written in on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday demonstrate. Addressing Schnitzler directly, Hermann Bahr wrote: “As no other among us, your graceful touch captured the last fascination of the waning of Vi- enna, you were the doctor at its deathbed, you loved it more than anyone else among us because you already knew there was no more hope” (); Egon Friedell opined that Schnitzler had “created a kind of topography of the constitution of the Viennese soul around , on which one will later be able to more reliably, more precisely and more richly orient oneself than on the most obese cultural historian” (); and Stefan Zweig noted that: [T]he unforgettable characters, whom he created and whom one still could see daily on the streets, in the theaters, and in the salons of Vienna on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, even yesterday… have suddenly disappeared, have changed. … Everything that once was this turn-of-the-century Vienna, this Austria before its collapse, will at one point… only be properly seen through Arthur Schnitzler, will only be called by their proper name by drawing on his works. () With the passing of time, the scope of Schnitzler’s representativeness has broadened. In his introduction to the new English translation of Schnitzler’s Dream Story (), Frederic Raphael sees Schnitzler not only as a Viennese writer; rather “Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa” (xii). -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Die Kunst Zu Hören

kunst hören die zu 1. Programmwoche 30. Dezember 2017 - 5. Januar 2018 Samstag, 30. Dezember 2017 09.04 – 09.35 Uhr FEATURE 60 Prozent Ost / 40 West Musikkontrolle à la DDR Von Gerhard Pötzsch Angefangen hat alles im Jahre 1990. Matthias Winkler, Student der Pflanzenproduktion, organisiert an der Universität in Halle einen Fakultätsball, und weil alles gut klappt, beantragt er eine Gewerbegenehmigung, bricht sein Studium ab und gründet die Agentur: MaWi. Kurz darauf wird Deutschland wiedervereinigt und die bis dahin allmächtige „Konzert- und Gastspieldirektion“ der DDR befindet sich in Auflösung. Es scheint wie ein Wunder, plötzlich sind alle Musiker verfügbar, auf die das DDR-Publikum jahrzehntelang sehnsüchtig gewartet hat. MaWi organisiert ihre Auftritte und holt sie nach Mitteldeutschland, unter ihnen Carlos Santana, die Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Van Morrison, Bob Dylan - insgesamt mehr als 3.000 Konzerte. Der Konzertmacher Matthias Winkler gestattet uns einen Blick hinter die Kulissen seiner Agenturarbeit. Regie: Andreas Meinetsberger Produktion: MDR 2017 - Ursendung - Sonntag, 31. Dezember 2017 – Silvester - 09.04 - 09.30 Uhr GOTT UND DIE WELT Die Perversion der Frohen Botschaft Ivan Illrichs Kritik an der Moderne Von Christoph Fleischmann In den 70er und 80er Jahren befeuerten seine Streitschriften zu Wirtschaft, Medizin und Schule die politische Debatte: Ivan Illich (1929 - 2002), katholischer Ex-Priester aus Österreich, wollte den Selbstverständlichkeiten der Moderne auf den Grund gehen. Die Herrschaft der Experten, befand er, mache den Menschen abhängig von Waren und Dienstleistungen. Am Anfang dieser Entwicklung steht für den Theologen der Versuch, die Liebe Gottes und die Zuwendung unter den Menschen zu institutionalisieren. Eine Perversion des christlichen Evangeliums. -

28Th Leeds International Film Festival Presents Leeds Free Cinema Week Experience Cinema in New Ways for Free at Liff 28 from 7 - 13 November

LIFF28th 28 Leeds International Film Festival CONGRATULATIONS TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire in a fantastic year for filmmaking in the region INCLUDING ‘71 GET SANTA SCREENING AT LIFF28 X + Y CATCH ME DADDY & LIFF28 OPENING NIGHT FILM TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Image: (2014) Testament of Youth James Kent Dir. bfi.org.uk/FilmFund Film Fund Ad LIFF 210x260 2014-10_FINAL 3.indd 1 27/10/2014 11:06 WELCOME From its beginnings at the wonderful, century-old Hyde Park Leeds International Film Festival is a celebration of both Picture House to its status now as a major national film event, film culture and Leeds itself, with this year more than 250 CONGRATULATIONS Leeds International Film Festival has always aimed to bring screenings, events and exhibitions hosted in 16 unique a unique and outstanding selection of global film culture locations across the city. Our venues for LIFF28 include the TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL to the city for everyone to experience. This achievement main hub of Leeds Town Hall, the historic cinemas Hyde is not possible without collaborations and this year we’ve Park Picture House and Cottage Road, other city landmarks FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR assembled our largest ever line-up of partners. From our like City Varieties, The Tetley, Left Bank, and Royal Armouries, long-term major funders the European Union and the British Vue Cinemas at The Light and the Everyman Leeds, in their Film Institute to exciting new additions among our supporting recently-completed Screen 4, and Chapel FM, the new arts The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire organisations, including Game Republic, Infiniti, and Trinity centre for East Leeds.