Visions of Vienna Visions of Vienna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinephilia Or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Elsaesser Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment. In: Marijke de Valck, Malte Hagener (Hg.): Cinephilia. Movies, Love and Memory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2005, S. 27– 43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell 3.0 Lizenz zur Verfügung Attribution - Non Commercial 3.0 License. For more information gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment Thomas Elsaesser The Meaning and Memory of a Word It is hard to ignore that the word “cinephile” is a French coinage. Used as a noun in English, it designates someone who as easily emanates cachet as pre- tension, of the sort often associated with style items or fashion habits imported from France. As an adjective, however, “cinéphile” describes a state of mind and an emotion that, one the whole, has been seductive to a happy few while proving beneficial to film culture in general. The term “cinephilia,” finally, re- verberates with nostalgia and dedication, with longings and discrimination, and it evokes, at least to my generation, more than a passion for going to the movies, and only a little less than an entire attitude toward life. -

Realist Cinema As World Cinema Non-Cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema Lúcia Nagib Realist Cinema As World Cinema

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema lúcia nagib Realist Cinema as World Cinema Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema Lúcia Nagib Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Photo by Mateo Contreras Gallego, for the film Birds of Passages (Pájaros de Verano, Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018), courtesy of the authors. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 751 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 921 5 doi 10.5117/9789462987517 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) L. Nagib / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2020 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents List of Illustrations 7 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 15 Part I Non-cinema 1 The Death of (a) Cinema 41 The State of Things 2 Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy 63 This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, Taxi Tehran, Three Faces 3 Film as Death 87 The Act of Killing 4 The Blind Spot of History 107 Colonialism in Tabu Part II -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

„O.K.“ Programm Von 08.10

Monatsübersicht Oktober/November Programm von 01.10. - 07.10.2020 Länge/FSK Do., 01.10. Fr., 02.10. Sa., 03.10. So., 04.10. Mo., 05.10. Di., 06.10. Mi., 07.10. Kino 1 Pelikanblut 127/16 20:15 20:15 20:15 20:15 20:15 20:15 Special: n.b. 17:00 Landstr. 35 Oktober/ Leinwand-Lyrik mit Ralph Turn- 20:00 69502 Hemsbach heim & Sherlock Holmes Tel.: 06201/43185 – November www.brennessel-kino.de Eine Nacht im Louvre 96/0 11:30 2020 17:45 17:45 17:45 17:45 17:45 17:45 Lichtspielhaus seit 1927 Meine wunderbar seltsame Woche 84/0 15:15 mit Tess Bis an die Grenze n.b. 11:00 Liebe Gäste der „Brennessel“, es geht endlich wieder los! Nach pandemiebe- Verleihung der BRONZENEN BRENNESSEL dingter Pause und Notprogramm starten wir Kino 2 David Copperfield - 120/6 20:30 20:30 20:30 20:30 20:30 20:30 nun – trotz einiger Einschränkungen, die Ihrer an Regisseur MICHAEL VERHOEVEN für „O.K“ Einmal Reichtum und zurück Sicherheit dienen - unser gewohntes Programm- schema. Als Dank für Ihre Unterstützung & Ge- duld während der Brennessel-Schließung präsen- Er hat das Nachkriegskino geprägt Der göttliche andere 92/6 18:00 18:00 18:00 18:00 18:00 18:00 18:00 tieren wir gleich drei Highlights: Am 3. Oktober wie kaum ein anderer deutscher wird der Leinwandlyriker Ralph Turnheim (www. leinwand-lyrik.de) Sherlock Holmes wieder aufer- Regisseur: Michael Verhoeven. Länge/FSK stehen lassen. Gäste, die Corona-Gutscheine für „O.K.“ Programm von 08.10. -

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

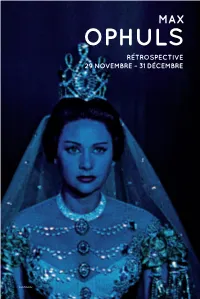

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

Research Opportunities in Munich Yvonne Shafer

FALL 1991 235 Research Opportunities in Munich Yvonne Shafer Munich is both a theatrical city and a city with a great deal of theatre. Throughout the city are interesting theatre buildings, important theatre collections, museums with theatrical material, and statues relating to theatre. The theatres, their archives, and theatre collections are accessible and public transportation in Munich is excellent. Theatre ranges from puppet shows to the classics-indeed, one can see Faust performed as a puppet show as Goethe first intended it. In the handsome theatre lobbies, there is an air of excitement and sophistication as the theatre-goers drink champagne and discuss the performances. The audiences are very responsive: they laugh a great deal in plays received very earnestly in America, applaud thunderously when a play is good, and boo long and loud when they do not care for a production. In order to give a picture of theatre research opportunities various types of productions will be described, followed by a discussion of the theatre museums and several of the famous theatres in the city. In May 1991 there were several dozen plays, ballets, operas and other theatrical performances from which to choose. There are major subsidized theatres and opera houses, small commercial theatres, theatres for children, and experimental groups. A range of plays available on a given night included Entertaining Mr. Sloane, The Threepenny Opera, Cooney and Chapman's Not Now, Darling, Durrenmatt's The Accident, and Jesus Christ Superstar. There were performances of a British science-fiction comedy presented by the Action Theatre London (in English) called Black Magic-Blue Love, a Psychothriller Murder Voices, and an evening of song and acting in the OFF-OFF-Theater Club. -

Novidades Adultos 2014

Los puentes de Madison = The bridges of Madison county / screenplay by Richard LaGravanese ; produced by Clint Eastwood and Kathleen Kennedy ; directed by Clint Eastwood. Ano de realización: 1995 Duración: 129 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM PUE [AUDV 19] Memorias de África = Out of Africa / directed by Sydney Pollack ; screenplay by Kurt Luedtke ; music by John Barry. Ano de realización: 1985 Duración: 154 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM MEM Lo que queda del día / una película de James Ivory ; screenplay by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala ; guión de Ruth Prawer Jhabvala ; música de Richard Robbins. Ano de realización: 1993 Duración: 129 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM LOQ Maridos y mujeres = Husbands and wives / una comedia escrita y dirigida por Woody Allen. Ano de realización: 1992 Duración: 103 min. Localización: CINE 791-C MAR Groundhog day = [Atrapado en el tiempo] / directed by Harold Ramis ; screenplay by Danny Rubin and Harol Rams ; produced by Trevor Albert and Harold Rams. Ano de realización: 1993 Duración: 97 min. Localización: CINE 791-C ATR La vida de Adèle / Abdellatif Kechiche. Ano de realización: 2013 Duración: 180 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM VID Los amantes del Círculo Polar / una película de Julio Medem. Ano de realización: 1998 Duración: 112 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM AMA Call me by your name / directed by Luca Guadagnino ; screenplay by James Ivory. Ano de realización: 2017 Duración: 127 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM CAL Midnight in Paris / escrita y dirigida por Woody Allen ; productores Letty Aronson, Stephen Tenenbaum, Jaume Roures. Ano de realización: 2011 Duración: 94 min. Localización: CINE 791-C MID El diario de Noa / dirigida por Nick Cassavetes ; guión de Jeremy Leven ; producida por Mark Johnson, Lynn Harris. -

The Swedish Film and Post-War American Films 1938

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 14 WEST 49TH STREET, NEW YORK TEUEPHONE: CIRCLE 7-7470 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Legends to the contrary notwithstanding, the negative of Erich von Stroheim's much-discussed film, Greed, has been preserved in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's vaults and it has therefore been possible to include this celebrated "masterpiece of realism" in the Museum of Modern Art Film Libraryfs current Series IV, The Swedish Film and Post-War American Films, Greed will be shown to Museum members on Wednesday, February 23rd, at 8:45 P.M. in the auditorium of the American Museum of Natural History, 77th Street and Central Park West. Thereafter it will be available to students of the film in i colleges and museums throughout the country. Greed, a faithful transcription into pictorial terms of Frank Norris1 novel, "McTeague," was created under unusual circumstances and met with a curious fate. It was not made in a studio, but on location in San Francisco. Whole blocks and houses were purchased as settings , walls knocked out to make the photography of real in teriors practicable. Every detail of the novel was reproduced at considerable expense of time and money, with a passionate and un compromising care for veracity. Eventually von Stroheim offered his producers his finished work, a final cut print twenty reels long which he proposed they should issue in two parts, and which bore no perceptible trace of those elements usually reckoned as "box office. The film was taken from him, cut down to the present ten reel ver sion and so released. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated