Honoring a World Citizen Who Never Walked

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCOBPS 2016 Program

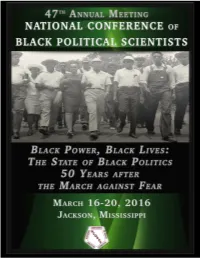

1 2 Dear Conference Attendees and Supporters: On behalf of the leadership of the National Conference of Black Political Scientists (NCOBPS), I welcome you to the 47th Annual Meeting of this beloved association. For nearly 50 years, NCOBPS has been an intellectual home and a vibrant forum for Black political scientists and other scholars who have seen it as our mission to use various forms of political and policy analysis so to enlighten, empower, and to serve Global Black communities. True to the vision of our founders and elders, our mission remains that of a ‘growing organization in the struggle for the liberation of African peoples.’ This mission is no less relevant today than it was nearly 50 years ago given that Global Black communities still confront an unnerving number of barriers to racial, political, and economic justice as intersected by other forms of oppression. The theme of this 47th Annual Meeting is “Black Power, Black Lives: 50 Years After the March Against Fear.” It pays tribute to a heroic activism, rooted in Mississippi soil, which countered white supremacy and demanded the full recognition of African Americans’ humanity and citizenship rights. This local struggle also continues. While you are here in Jackson, Mississippi, one of the activist headquarters and continuing battlefields for human rights equality, enjoy yourself (eat some catfish, listen to some blues music, and see the sights) but of course take full advantage of all of what our brilliant conference organizers and local arrangements committee have provided. We extend our great thanks for their extreme dedication and hard work! We also extend a warm greeting to all of our guests and a heart-felt thanks to all of our co-sponsors and local partners. -

Caribbeanization of Black Politics Sharon D

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 Yvette Clarke U.S. Representative (D.-MA) CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Associate Managing Editor Julia Jordan-Zachery Providence College Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Augusta University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, St. Louis Niambi Carter—Howard University Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Marion Brown—Brown University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Nyron Crawford—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Heath Fogg-Davis—Temple University H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Christina Rivers—DePaul University Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Neil Roberts—Williams College Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Fatemeh Shafiei—Spelman College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

American Political Science Review

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.139, on 01 Oct 2021 at 19:27:59, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000216 MAY 2021 | VOLUME 115| NUMBER 2 2021 | VOLUME MAY Review Science Political American LEAD EDITORS David Broockman Alan Jacobs Mark Pickup Clarissa Hayward UC Berkeley, USA University of British Columbia, Canada Simon Fraser University, Canada Washington University in St. Louis, Nadia E. Brown Amaney Jamal Melanye Price USA Purdue University, USA Princeton University, USA Prairie View A&M University, USA Kelly M. Kadera Renee Buhr Juliet Johnson Karthick Ramakrishnan University of Iowa, USA University of St. Thomas, USA McGill University, Canada UC Riverside, USA Pradeep Chhibber Michael Jones-Correa Gina Yannitell Reinhardt EDITORS UC Berkeley, USA University of Pennsylvania, USA University of Essex, UK Sharon Wright Austin Cathy Cohen Kimuli Kasara Andrew Reynolds University of Florida, USA University of Chicago, USA Columbia University, USA University of North Carolina, USA Michelle L. Dion Katherine Cramer Helen M. Kinsella Emily Hencken Ritter McMaster University, Canada University of Wisconsin–Madison, University of Minnesota, USA Vanderbilt University, USA Celeste Montoya USA Brett Ashley Leeds Molly Roberts University of Colorado, Boulder, USA Paisley Currah Rice University, USA UC San Diego, USA Julie Novkov CUNY, USA Ines Levin Melvin Rogers University at Albany, SUNY, USA Christian Davenport UC Irvine, USA Brown University, USA Valeria Sinclair-Chapman University of Michigan, USA Jacob T. Levy Nita Rudra Purdue University, USA Alexandre Debs McGill University, Canada Georgetown University, USA Dara Strolovitch Yale University, USA Pei-te Lien Burcu Savun Princeton University, USA Jacqueline H. -

Officers and Staff 2019-2020

91st Annual Conference Officers and Staff 2019-2020 President . Jeff Gill, American University President Elect . Cherie Maestas, Purdue University Vice President . Marc Hetherington, University of North Carolina Vice President Elect . Susan Haire, University of Georgia Executive Director . Robert Howard, Georgia State University Secretary . Angela Lewis, University of Alab ama at Birmingham Treasurer . Kerstin Hamann, University of Central Florida Past President . David E. Lewis, Vanderbilt University Past Vice President . Christopher Wlezien, University of Texas, Austin Executive Council . Richard Forgette, University of Mississippi R. Keith Gaddie, University of Oklahoma Dan Gillion, University of Pennsylvania Martha Kropf, University of North Carolina, Charlotte Santiago Olivella, University of North Carolina L. Marvin Overby, University of Missouri Richard Pacelle, University of Tennessee, Knoxville Elizabeth Maggie Penn, University of Chicago Alixandra Yanus, High Point University Journal of Politics Editors . Jeffery A. Jenkins, University of Southern California, Editor-in Chief Ernesto Calvo, University of Maryland Tom S. Clark, Emory University Courtenay R. Conrad, University of California at Merced Jacob T. Levy, McGill University Neil Malhotra, Stanford University Margit Tavits, Washington University in St. Louis SPSA Staff . Patricia A. Brown, Operations Manager Richard N. Engstrom, Director of Professional Development/Conference Manager Garry C. Brown, Conference Operations Associate Graphic Design . Mallory McLendon, Graphic & Exhibit Design 4 Southern Political Science Association • 91st Annual Conference • January 9–11, 2020 • San Juan, Puerto Rico 91st Annual Conference Dear SPSA conference participants, Welcome to the 2020 meeting of the Southern Political Science Association (SPSA) here in San Juan Puerto Rico. Tis is the 91st annual meeting of the SPSA, which is one of the most diverse and welcoming meetings in political science. -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana

Case 3:20-cv-00308-SDD-RLB Document 22 06/04/20 Page 1 of 6 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA TELISA CLARK, et al., Plaintiffs, Case No.: 3:20-cv-00308-SDD-RLB v. JOHN BEL EDWARDS, et al., Defendants. PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Plaintiffs Telisa Clark, Lakeshia Barnett, Martha Christian Green, Crescent City Media Group (“CCMG”), and League of Women Voters Louisiana (“LWVLA”) (collectively, “Plaintiffs”) respectfully move for a preliminary injunction restraining Defendants for all upcoming 2020 elections from enforcing (1) the requirement to qualify for an excuse to vote by absentee ballot (the “Excuse Requirement”), see La. Rev. Stat. § 18:1303; (2) the requirement to have another person witness the absentee voter’s signature and then sign the absentee ballot envelope (the “Witness Requirement”), see La. Rev. Stat. § 18:1306(E.)(2)(a)–(b); and (3) the failure to provide absentee voters with notice of defects with their mail-in absentee ballot and an opportunity to cure such defects so that their votes may be counted (the “Cure Prohibition”), see La. Rev. Stat. § 18:1313. The United States and Louisiana are facing an unprecedented global pandemic that epidemiologists predict will continue into the fall, when the general election in November is expected to draw high voter turnout. As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, Louisiana election officials, including Defendants Governor Edwards and Secretary of State Ardoin have already Case 3:20-cv-00308-SDD-RLB Document 22 06/04/20 Page 2 of 6 concluded that the state’s voting rules must change to protect voters and ensure safe, free, fair, and equal elections during the pandemic. -

Sekou Franklin NCOBPS Vice-President: Tiffany Willoughby-Herard Executive Director

NCOBPS President: Sekou Franklin NCOBPS Vice-President: Tiffany Willoughby-Herard Executive Director: Kathie Stromile Golden Co-Chairs of the Annual Conference: Gladys Mitchell-Walthour, Donn Worgs, Ollie Johnson Black Politics and Black People as the Conscience of Nations Conference Co-Chairs: Gladys Mitchell-Walthour, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Ollie Johnson, Wayne State University Donn Worgs, Towson University The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) will be celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2021. The CBC has been deemed the “Conscience of Congress” in recognition of its broader commitment to racial and economic justice for African Americans, Africa, and the Diaspora. In light of the CBC’s 50th anniversary, the National Conference of Black Political Science (NCOBPS) seeks papers, panels, and roundtables that examine how Black people in the United States and the African Diaspora are often viewed as the “Conscience” of their nation-states and the moral authority in social movements and institutional politics. This includes Black voters and candidates, as well as Black women who are often the moral compass that shapes the direction of Black politics and the nation-states. The Black Lives Matter-inspired protests in the Summer 2020 further exemplify the transformative impact of Black political agency. Even in Latin America Black women are leading constituents in elections and social movements, such as in Brazil, where they have been critical in shaping presidential and state elections. The conference theme—“Black Politics and Black People as the Conscience of Nations”—examines the multi-layered ways in which Black Politics, both domestic and abroad, continue to serve as moral anchors for advancing liberation, justice, and ameliorative policies. -

Fall 2009 Years Ago, I Assumed Goal Is to Develop a That I Would Be in the Nationally Recognized Inside This Issue: Job a Short Time and Ph.D

Department of Political Science Newsletter Message from the Department Head When I agreed to serve ing, research and ser- as Interim Head two vice. My first major Fall 2009 years ago, I assumed goal is to develop a that I would be in the nationally recognized Inside this issue: job a short time and Ph.D. program. To do that my role was es- this, I will work to en- Personnel News 2 sentially that of care- sure that every mem- taker. Now, as I begin ber of the faculty has Awards 3 a five-year term as an active research Head, I think it is im- agenda and is publish- Faculty Spotlight 4 portant to articulate a ing scholarly books vision for the Depart- and high-quality jour- Research Grants 4 ment and an agenda nal articles. I must also must be team efforts, for my headship. work to see that our and we have a strong Outreach Activities 5 Ph.D. graduates obtain team in place My vision is of a de- faculty positions at now. The role of the Other News 5 partment that is a na- major research univer- department head ... tional leader in teach- sities. Of course, these (continued next page) Faculty Research 6 Graduate Student 13 Editor’s Note Research Alumni News 14 Thanks to many peo- long. It is so gratifying touch with the depart- Opportunities for 16 ple’s help and coopera- to hear from our ment and continue to Giving tion, our expanded de- alumni and to know send us your updated partmental newsletter they are doing so well. -

Newsletter-Partisan-Summer-2009

Department of Political Science University of Florida Summer 2009 BATTLEGROUND VOTERS: The 2008 Presidential Election in Florida by The 2008 election marked several mile- Michael Martinez stones. Hillary Clinton entered the cam- any "swift boat" attacks that might be launched by independent paign as the first female frontrunner for a groups, and to pursue a 50-state strategy in an effort to change the major-party presidential nomination, only to electoral map. lose a long and arduous contest to Barack Despite the historic result, 2008 followed some more-or-less Obama, whose fundraising and organiza- usual patterns. The Obama campaign did shrink the GOP's geo- tional prowess led to his becoming the first graphic base but, in the end, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida re- African-American presidential nominee of a mained (as they were in 2000 and 2004) the key battleground states major political party. John McCain's path to through which McCain would try to mount one last comeback. the Republican nomination was more con- Also, in deciding how to cast their ballots, Florida voters relied on ventional, after early favorite Rudy Giuliani two of the simplest and most time-tested cues available. showed why skipping the early primary and The first cue was partisanship. Among registered voters in a caucus states is likely to remain a dubious statewide October pre-election survey, Democrats enjoyed a 38-34 strategy. McCain chose Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as the first percent advantage over Republicans in party identification, with the female Republican vice-presidential nominee, and she and Senator balance (28%) identifying as Independents or expressing no prefer- Joe Biden became the first pair of running mates in memory to hail ence. -

Volume 18 National Political Science Review Challenging the Legacies of Racial Resentment

THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Associate Managing Editor Julia Jordan-Zachery Providence College Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Keisha Blain University of Iowa EDITORIAL BOARD Melina Abdullah - California State University, Keisha Lindsay - University of Wisconsin Los Angeles Clarence Lusane - American University Anthony Affigne - Providence College Maruice Mangum - Texas Southern University Nikol Alexander-Floyd - Rutgers University Lorenzo Morris - Howard University Russell Benjamin - Northeastern Illinois University Richard T. Middleton IV - University of Nadia Brown - Purdue University Missouri-St. Louis Niambi Carter - Howard University Byron D’Andra Orey - Jackson State University Cathy Cohen - University of Chicago Marion Orr - Brown University Dewey Clayton - University of Louisville Dianne Pinderhughes - University of Notre Dame Nyron Crawford - Temple University Matt Platt - Morehouse College Heath Fogg-Davis - Temple University H.L.T. Quan - Arizona State University Pearl Ford Dowe - University of Arkansas Boris Ricks - California State University, Northridge Kamille Gentles Peart - Roger Williams University Christina Rivers - DePaul University Daniel Gillion - University of Pennsylvania Neil Roberts - Williams College Ricky Green - California State University, Sacramento Fatemeh Shafiei - Spelman College Jean-German Gros -

2009 Vancouver Meeting

Western Political Science Association CONFERENCE THEME: IDEAS, INTERESTS AND INSTITUTIONS MARCH 19 - 21, 2009 Vancouver, BC CANADA Front Cover Photo: Elizabeth F. Moulds TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TRIBUTE TO ELIZABETH (BETTY) MOULDS.............................................ii WELCOME AND SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................iii WESTERN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION OFFICERS.................. v COMMITTEES OF THE WESTERN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION .....................................................................................vii WPSA ANNUAL AWARDS GUIDELINES ...................................................ix WPSA AWARDS TO BE ANNOUNCED AT THE 2009 MEETING .............xi CALL FOR PAPERS 2010 MEETING ........................................................xii MEETING SCHEDULE AND SPECIAL EVENTS........................................ 1 SCHEDULE OF PANELS ............................................................................ 4 PANEL LISTINGS: THURSDAY, 8:00 AM – 9:45 AM................................................... 32 THURSDAY, 10:00 AM – 11:45 AM................................................... 44 THURSDAY, 1:15 PM – 3:00 PM................................................... 55 THURSDAY, 3:15 PM – 5:00 PM................................................... 68 FRIDAY, 8:00 AM – 9:45 AM .................................................. 80 FRIDAY, 10:00 AM – 11:45 AM .................................................. 91 FRIDAY, 1:15 PM – 3:00 PM ................................................ 102 -

Caribbean Studies and Digital Humanities Submission Title

Descriptive Title: Migration, Mobility, and Sustainability: Caribbean Studies and Digital Humanities Submission Title: Opportunity ID: 20180313-HT Opportunity Title: Institutes for Advanced Topics in the Digital Humanities Agency Name: National Endowment for the Humanities Table of Contents Application For Federal Domestic Assistance - Short Organizational V1.1 .....................................3 Research & Related Project/Performance Site Location(s) V2.0.....................................................6 Supplementary Cover Sheet for NEH Grant Programs V3.0 ...........................................................7 Attachments V1.0.............................................................................................................................8 Budget Narrative Attachment Form V1.0 .......................................................................................83 OMB Number: 4040-0003 Expiration Date: 7/30/2011 APPLICATION FOR FEDERAL DOMESTIC ASSISTANCE – Short Organizational Version 01 1. NAME OF FEDERAL AGENCY: National Endowment for the Humanities 2. CATALOG OF FEDERAL DOMESTIC ASSISTANCE NUMBER: 45.169 CFDA TITLE: Promotion of the Humanities Office of Digital Humanities 3. DATE RECEIVED: SYSTEM USE ONLY 4. FUNDING OPPORTUNITY NUMBER: 20180313-HT TITLE: Institutes for Advanced Topics in the Digital Humanities 5. APPLICANT INFORMATION a. Legal Name: University of Florida b. Address: Street 1: Street 2: 207 Grinter Hall PO Box 115500 City: County/Parish: Gainesville State: Province: FL: Florida Country: Zip/Postal -

American Political Science Review

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.22, on 26 Sep 2021 at 11:59:13, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000216 MAY 2021 | VOLUME 115| NUMBER 2 2021 | VOLUME MAY Review Science Political American LEAD EDITORS David Broockman Alan Jacobs Mark Pickup Clarissa Hayward UC Berkeley, USA University of British Columbia, Canada Simon Fraser University, Canada Washington University in St. Louis, Nadia E. Brown Amaney Jamal Melanye Price USA Purdue University, USA Princeton University, USA Prairie View A&M University, USA Kelly M. Kadera Renee Buhr Juliet Johnson Karthick Ramakrishnan University of Iowa, USA University of St. Thomas, USA McGill University, Canada UC Riverside, USA Pradeep Chhibber Michael Jones-Correa Gina Yannitell Reinhardt EDITORS UC Berkeley, USA University of Pennsylvania, USA University of Essex, UK Sharon Wright Austin Cathy Cohen Kimuli Kasara Andrew Reynolds University of Florida, USA University of Chicago, USA Columbia University, USA University of North Carolina, USA Michelle L. Dion Katherine Cramer Helen M. Kinsella Emily Hencken Ritter McMaster University, Canada University of Wisconsin–Madison, University of Minnesota, USA Vanderbilt University, USA Celeste Montoya USA Brett Ashley Leeds Molly Roberts University of Colorado, Boulder, USA Paisley Currah Rice University, USA UC San Diego, USA Julie Novkov CUNY, USA Ines Levin Melvin Rogers University at Albany, SUNY, USA Christian Davenport UC Irvine, USA Brown University, USA Valeria Sinclair-Chapman University of Michigan, USA Jacob T. Levy Nita Rudra Purdue University, USA Alexandre Debs McGill University, Canada Georgetown University, USA Dara Strolovitch Yale University, USA Pei-te Lien Burcu Savun Princeton University, USA Jacqueline H.