Reflections on a Harlem Professor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children of Stuggle Learning Guide

Library of Congress LIVE & The Smithsonian Associates Discovery Theater present: Children of Struggle LEARNING GUIDE: ON EXHIBIT AT THE T Program Goals LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: T Read More About It! Brown v. Board of Education, opening May T Teachers Resources 13, 2004, on view through November T Ernest Green, Ruby Bridges, 2004. Contact Susan Mordan, (202) Claudette Colvin 707-9203, for Teacher Institutes and T Upcoming Programs school tours. Program Goals About The Co-Sponsors: Students will learn about the Civil Rights The Library of Congress is the largest Movement through the experiences of three library in the world, with more than 120 young people, Ruby Bridges, Claudette million items on approximately 530 miles of Colvin, and Ernest Green. They will be bookshelves. The collections include more encouraged to find ways in their own lives to than 18 million books, 2.5 million recordings, stand up to inequality. 12 million photographs, 4.5 million maps, and 54 million manuscripts. Founded in 1800, and Education Standards: the oldest federal cultural institution in the LANGUAGE ARTS (National Council of nation, it is the research arm of the United Teachers of English) States Congress and is recognized as the Standard 8 - Students use a variety of national library of the United States. technological and information resources to gather and synthesize information and to Library of Congress LIVE! offers a variety create and communicate knowledge. of program throughout the school year at no charge to educational audiences. Combining THEATER (Consortium of National Arts the vast historical treasures from the Library's Education Associations) collections with music, dance and dialogue. -

Coretta Scott King Book Awards Author Winner Is Given to Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin for “March Book: Three.”

Coretta Scott King Book Award Complete List of Recipients—by Year The 2010s 2017 Author Award Winner The 2017 Coretta Scott King Book Awards Author Winner is given to Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin for “March Book: Three.” 2017 Illustrator Award Winner The 2017 Coretta Scott King Book Awards Illustrator Winner is given to Javaka Steptoe, illustrator and author of “Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat,” published by Little, Brown and Company.” 2017 Author Honour Books: As Brave As You, by Jason Reynolds, a Caitlyn Dlouhy Book, published by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division. Freedom Over Me: Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life by Ashley Bryan, written and illustrated by Ashley Bryan, a Caitlyn Dlouhy Book, published by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division. 2017 Illustrator Honour Books: “Freedom in Congo Square,” illustrated by R. Gregory Christie, written by Carole Boston Weatherford, and published by Little Bee Books, an imprint of Bonnier Publishing Group. “Freedom Over Me: Eleven slaves, their lives and dreams brought to life by Ashley Bryan,” written and illustrated by Ashley Bryan, published by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, “In Plain Sight,” illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, written by Richard Jackson, a Neal Porter book, published by Roaring Brook Press. 2016 Author Award Winner The 2016 Coretta Scott King Book Awards Author Winner is given to Rita Williams-Garcia, author of “Gone Crazy in Alabama.” 2016 Illustrator Award Winner The 2016 Coretta Scott King Book Awards Illustrator Winner is given to Bryan Collier, illustrator of “Trombone Shorty.” 2016 Author Honor Books: All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely, and published by Atheneum Books for Young Readers an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division. -

Hollywood: the Shock of Freedom in Films -- Printout -- TIME

Back to Article Click to Print Friday, Dec. 08, 1967 Hollywood: The Shock of Freedom in Films (See Cover) Two girls embrace, then enjoy a long, lingering kiss that ends only ' when a male intruder appears. A vulpine criminal in a sumptuous penthouse pulls aside a window curtain to look down at the street. When he releases the curtain, he is abruptly in another apartment. He crosses the thickly carpeted living room to peer into a bedroom; when he turns back, the living room is empty and bare- floored. In the midst of an uproariously funny bank robbery, a country-boy hoodlum fires his pistol; the tone of the scene shifts in a split second from humor to horror as the bloodied victim dies. At first viewing, these scenes would appear to be photomontages from an underground-film festival. But The Fox, based on a D. H. Lawrence story with a lesbian theme, is soon to be released nationally, starring Sandy Dennis. Point Blank, with Lee Marvin, is in its plot an old-fashioned shoot-em-down but in its technique a catalogue of the latest razzle-dazzle cinematography. Bonnie and Clyde is not only the sleeper of the decade but also, to a growing consensus of audiences and critics, the best movie of the year. Differing widely in subject and style, the films have several things in common. They are not what U.S. movies used to be like. They enjoy a heady new freedom from formula, convention and censorship. And they are all from Hollywood. Poetry & Rhythm. Hollywood was once described as the only asylum run by its inmates. -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS Exclusive Auction Event of the Legendary Film Producer and Paramount Studio Executive of Hollywood’s Landmark Films, Chinatown, The Godfather, The Godfather II, Love Story, Rosemary’s Baby, Serpico, True Grit and More Robert Evans’ Fine Art Collection including Works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Helmut Newton, 1995 Jaguar XJS 2+2 Convertible, Furniture from his Beverly Hills Mansion, Film Scripts, Golden Globe Award, Rolodex, and More Offered for the First Time at Auction SATURDAY, OCTOBER 24TH, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (September 8th, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS, a celebration of the dazzling life and singular career of the legendary American film producer and studio executive, Robert Evans, who produced some of American cinema’s finest achievements and championed a new generation of commercial and artistic filmmaking from the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet, Roman Polanski, John Schlesinger and more in Hollywood. This exclusive auction event will take place Saturday, October 24th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. PAGE 1 Julien’s Auctions | 8630 Hayden Place, Culver City, California 90232 | Phone: 310-836-1818 | Fax: 310-836-1818 © 2003-2020 Julien’s Auctions JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ROBERT EVANS PRESS RELEASE Evans’ Jaguar convertible On offer is a spectacular collection of the Hollywood titan’s fine/decorative art, classic car, household items, film scripts, memorabilia and awards from Evans’ most iconic film productions, Chinatown, The Godfather, The Godfather II, Love Story, Rosemary’s Baby, Serpico, True Grit, and more. -

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

National Delta Kappa Alpha

,...., National Delta Kappa Alpha Honorary Cinema Fraternity. 31sT ANNIVERSARY HONORARY AWARDS BANQUET honoring GREER GARSON ROSS HUNTER STEVE MCQUEEN February 9, 1969 TOWN and GOWN University of Southern California PROGRAM I. Opening Dr. Norman Topping, President of USC II. Representing Cinema Dr. Bernard R. Kantor, Chairman, Cinema III. Representing DKA Susan Lang Presentation of Associate Awards IV. Special Introductions Mrs. Norman Taurog V. Master of Ceremonies Jerry Lewis VI. Tribute to Honorary l\llembers of DKA VII. Presentation of Honorary Awards to: Greer Garson, Ross Hunter, Steve McQueen VIII. In closing Dr. Norman Topping Banquet Committee of USC Friends and Alumni Mrs. Tichi Wilkerson Miles, chairman Mr. Stanley Musgrove Mr. Earl Bellamy Mrs. Lewis Rachmil Mrs. Harry Brand Mrs. William Schaefer Mr. George Cukor Mrs. Sheldon Schrager Mrs. Albert Dorskin Mr. Walter Scott Mrs. Beatrice Greenough Mrs. Norman Taurog Mrs. Bernard Kantor Mr. King Vidor Mr. Arthur Knight Mr. Jack L. Warner Mr. Jerry Lewis Mr. Robert Wise Mr. Norman Jewison is unable to be present this evening. He will re ceive his award next year. We are grateful to the assistance of 20th Century Fox, Universal studios, United Artists and Warner Seven Arts. DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA In 1929, the University of Southern California in cooperation with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offered a course described in the Liberal Arts Catalogue as : Introduction to Photoplay: A general introduction to a study of the motion picture art and industry; its mechanical founda tion and history; the silent photoplay and the photoplay with sound and voice; the scenario; the actor's art; pictorial effects; commercial requirements; principles of criticism; ethical and educational features; lectures; class discussions, assigned read ings and reports. -

Dubai Gets Ready to Go Kosher After Israel Peace Deal

12 Established 1961 Lifestyle Features Wednesday, October 21, 2020 Julien’s Auctions announces property from the estate of Robert Evans A color photograph of Robert Evans (right) and Jack Nicholson is dis- Robert Evans’s Hollywood Walk of Fame Star which he received in May Robert Evans’s 1974 Golden Globe Award from the movie “Chinatown” played during an auction preview of “Property from the Estate of Robert 2003 (est. $3,000-$5,000) is displayed during an auction preview of (est. $3,000-$5,000). Evans” at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills, California. —AFP photos “Property from the Estate of Robert Evans” . spectacular auction of nearly 600 items from ness contacts including Wes Anderson, Army Archerd, the dazzling life and singular career of the leg- Warren Beatty, Candice Bergen, Jacqueline Bissett, Aendary American film producer and studio Peter Bogdanovich, Faye Dunaway Mia Farrow, Jack executive, Robert Evans, who produced some of Nicholson, Mario Puzo, Rob Reiner, Arnold American cinema’s finest achievements and champi- Schwarzenegger, Liz Smith, Aaron Spelling and oned a new generation of commercial and artistic Elizabeth Taylor to name just a few; Evans’ signature filmmaking from the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, wardrobe of cashmere sweaters, silk ties, vests, bolo Sidney Lumet, Roman Polanski, John Schlesinger and ties and Oliver Peoples tinted eyeglasses; his fine art more in Hollywood. The Hollywood titan’s fine/deco- collection including works by Bernard Buffet, Helmut rative art, classic car, household items, film scripts, Newton and Pierre-Paul Prud’hon; as well as his 1995 memorabilia and awards from Evans’ most iconic film Jaguar XJS 2+2 convertible, furniture and d?àcor productions, Chinatown, The Godfather, The from his Beverly Hills Mansion and more. -

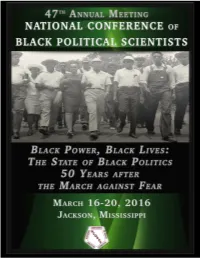

NCOBPS 2016 Program

1 2 Dear Conference Attendees and Supporters: On behalf of the leadership of the National Conference of Black Political Scientists (NCOBPS), I welcome you to the 47th Annual Meeting of this beloved association. For nearly 50 years, NCOBPS has been an intellectual home and a vibrant forum for Black political scientists and other scholars who have seen it as our mission to use various forms of political and policy analysis so to enlighten, empower, and to serve Global Black communities. True to the vision of our founders and elders, our mission remains that of a ‘growing organization in the struggle for the liberation of African peoples.’ This mission is no less relevant today than it was nearly 50 years ago given that Global Black communities still confront an unnerving number of barriers to racial, political, and economic justice as intersected by other forms of oppression. The theme of this 47th Annual Meeting is “Black Power, Black Lives: 50 Years After the March Against Fear.” It pays tribute to a heroic activism, rooted in Mississippi soil, which countered white supremacy and demanded the full recognition of African Americans’ humanity and citizenship rights. This local struggle also continues. While you are here in Jackson, Mississippi, one of the activist headquarters and continuing battlefields for human rights equality, enjoy yourself (eat some catfish, listen to some blues music, and see the sights) but of course take full advantage of all of what our brilliant conference organizers and local arrangements committee have provided. We extend our great thanks for their extreme dedication and hard work! We also extend a warm greeting to all of our guests and a heart-felt thanks to all of our co-sponsors and local partners. -

Honoring a World Citizen Who Never Walked

WALK THE HIGH ROAD: CAMOUFLAGING RACISM AND THE FLORIDA EXPERIENCE ALONG DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. BOUVELARD By STEVEN FENTON SPINA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Steven Fenton Spina 2 In recognition of the street naming pioneers featured in this dissertation: James and Joanna Tokley and their compatriots in Tampa Charles Smith for his efforts in Palmetto Irene Dobson and her neighbors in Zephyrhills LeRoy Boyd and Movement for Change in Pensacola. Without their courage and conviction, change would not have been realized. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my dissertation committee comprised of Dr. Sharon Austin, Dr. Larry Dodd, Dr. Stephanie Evans, Dr. David Hedge and Dr. Lynn Leverty for their guidance, patience and scholarly insights to this work. To my wife, Judy, who has believed in this project and supported me through the years of completing this dream of mine, and I recognize Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose long shadow is cast upon these pages and who inspired this project. His words below contribute to the title and ideals put forth within this dissertation. We can choose either to walk the high road of human brotherhood or to tread the low road of man‟s inhumanity to man. History has thrust upon our generation an indescribably important destiny – to complete a process of democratization which our nation has too long developed too slowly. The future of America is bound up in the present crisis. -

Caribbeanization of Black Politics Sharon D

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 Yvette Clarke U.S. Representative (D.-MA) CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Associate Managing Editor Julia Jordan-Zachery Providence College Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Augusta University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, St. Louis Niambi Carter—Howard University Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Marion Brown—Brown University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Nyron Crawford—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Heath Fogg-Davis—Temple University H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Christina Rivers—DePaul University Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Neil Roberts—Williams College Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Fatemeh Shafiei—Spelman College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

American Political Science Review

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.139, on 01 Oct 2021 at 19:27:59, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000216 MAY 2021 | VOLUME 115| NUMBER 2 2021 | VOLUME MAY Review Science Political American LEAD EDITORS David Broockman Alan Jacobs Mark Pickup Clarissa Hayward UC Berkeley, USA University of British Columbia, Canada Simon Fraser University, Canada Washington University in St. Louis, Nadia E. Brown Amaney Jamal Melanye Price USA Purdue University, USA Princeton University, USA Prairie View A&M University, USA Kelly M. Kadera Renee Buhr Juliet Johnson Karthick Ramakrishnan University of Iowa, USA University of St. Thomas, USA McGill University, Canada UC Riverside, USA Pradeep Chhibber Michael Jones-Correa Gina Yannitell Reinhardt EDITORS UC Berkeley, USA University of Pennsylvania, USA University of Essex, UK Sharon Wright Austin Cathy Cohen Kimuli Kasara Andrew Reynolds University of Florida, USA University of Chicago, USA Columbia University, USA University of North Carolina, USA Michelle L. Dion Katherine Cramer Helen M. Kinsella Emily Hencken Ritter McMaster University, Canada University of Wisconsin–Madison, University of Minnesota, USA Vanderbilt University, USA Celeste Montoya USA Brett Ashley Leeds Molly Roberts University of Colorado, Boulder, USA Paisley Currah Rice University, USA UC San Diego, USA Julie Novkov CUNY, USA Ines Levin Melvin Rogers University at Albany, SUNY, USA Christian Davenport UC Irvine, USA Brown University, USA Valeria Sinclair-Chapman University of Michigan, USA Jacob T. Levy Nita Rudra Purdue University, USA Alexandre Debs McGill University, Canada Georgetown University, USA Dara Strolovitch Yale University, USA Pei-te Lien Burcu Savun Princeton University, USA Jacqueline H. -

Officers and Staff 2019-2020

91st Annual Conference Officers and Staff 2019-2020 President . Jeff Gill, American University President Elect . Cherie Maestas, Purdue University Vice President . Marc Hetherington, University of North Carolina Vice President Elect . Susan Haire, University of Georgia Executive Director . Robert Howard, Georgia State University Secretary . Angela Lewis, University of Alab ama at Birmingham Treasurer . Kerstin Hamann, University of Central Florida Past President . David E. Lewis, Vanderbilt University Past Vice President . Christopher Wlezien, University of Texas, Austin Executive Council . Richard Forgette, University of Mississippi R. Keith Gaddie, University of Oklahoma Dan Gillion, University of Pennsylvania Martha Kropf, University of North Carolina, Charlotte Santiago Olivella, University of North Carolina L. Marvin Overby, University of Missouri Richard Pacelle, University of Tennessee, Knoxville Elizabeth Maggie Penn, University of Chicago Alixandra Yanus, High Point University Journal of Politics Editors . Jeffery A. Jenkins, University of Southern California, Editor-in Chief Ernesto Calvo, University of Maryland Tom S. Clark, Emory University Courtenay R. Conrad, University of California at Merced Jacob T. Levy, McGill University Neil Malhotra, Stanford University Margit Tavits, Washington University in St. Louis SPSA Staff . Patricia A. Brown, Operations Manager Richard N. Engstrom, Director of Professional Development/Conference Manager Garry C. Brown, Conference Operations Associate Graphic Design . Mallory McLendon, Graphic & Exhibit Design 4 Southern Political Science Association • 91st Annual Conference • January 9–11, 2020 • San Juan, Puerto Rico 91st Annual Conference Dear SPSA conference participants, Welcome to the 2020 meeting of the Southern Political Science Association (SPSA) here in San Juan Puerto Rico. Tis is the 91st annual meeting of the SPSA, which is one of the most diverse and welcoming meetings in political science.