METHODIST HISTORY April 2020 Volume LVIII Number 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About Absalom Jones Priest 1818

The Reverend Absalom Jones November 7, 1746 – February 13, 1818 The life and legacy of The Reverend Absalom Jones, first African American priest of The Episcopal Church is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, his faith, and his commitment to the causes of freedom, justice and self-determination. Jones was born into slavery in Sussex County, Delaware on November 6, 1746. During the 72 years of his life, he grew to become one of the foremost leaders among persons of African descent during the post-revolutionary period. In his younger years in Delaware, Absalom sought help to learn to read. When he was 16, his owner Benjamin Wynkoop brought him to Philadelphia where he served as a clerk and handyman in a retail store. He was able to work for himself in the evenings and keep his earnings. He also briefly attended a school run by the Quakers where he learned mathematics and handwriting. In 1770, he married Mary Thomas and purchased her freedom. It was until 1784 that he obtained his own freedom through manumission. He also owned several properties. During this period, he met Richard Allen, who became a life-long friend. In 1787, they organized the Free African Society as a social, political and humanitarian organization helping widows and orphans and assisting in sick relief and burial expenses. Jones and Allen were also lay preachers at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, Philadelphia, PA where their evangelistic efforts met with great success and their congregation multiplied ten-fold. As a result, racial tensions flared and ultimately they led an historic walk out from St. -

Freeborn Garrettson and African Methodism

Methodist History, 37: 1 (October 1998) BLACK AND WHITE AND GRAY ALL OVER: FREEBORN GARRETTSON AND AFRICAN METHODISM IAN B. STRAKER Historians, in describing the separation of Africans from the Methodist Episcopal Church at the tum of the 19th century, have defined that separation by the possible reasons for its occurrence rather than the context within which it occurred.' Although all historians acknowledge, to some degree, that racial discrimination led to separate houses of worship for congregants of African descent, few have probed the ambivalence of that separation as a source of perspective on both its cause and degree; few have both blamed and credited the stolid ambiguity of Methodist racial interaction for that separation. Instead, some historians have emphasized African nationalism as a rea son for the departure of Africans from the Methodist Episcopal Church, cit ing the human dignity and self-respect Africans saw in the autonomy of sep arate denominations. Indeed, faced with segregated seating policies and with the denial of both conference voting rights and full ordination, Africans struck out on their own to prove that they were as capable as whites of fully con ducting their own religious lives. Other historians have placed the cause for the separation within the more benign realm of misunderstandings by the Africans about denominational polity, especially concerning the rights of local congregations to own and control church property. The accuracy of each point of view notwithstanding, black hnd white racial interaction in early Methodism is the defining context with which those points of view must be reconciled. Surely, a strident nationalism on the part of Africans would have required a renunciation, or even denunciation, of white Methodists and "their" church, which is simply not evident in the sources. -

NOTES and DOCUMENTS the African Methodists of Philadelphia

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS The African Methodists of Philadelphia, 1794-1802 The story of the exodus of the black Methodists from St. George's Church in Philadelphia in the late eighteenth century and the subse- quent founding of Bethel African Methodist Church was first told by Richard Allen in a memoir written late in his life.1 Allen's story, fa- mous as a symbol of black independence in the Revolutionary era, il- lustrates the extent to which interracial dynamics characterized social life and popular religion in post-Revolutionary Philadelphia. The birth of Allen's congregation in the city was not an accident: Philadelphia's free black population had grown rapidly with the migration of ex-slaves attracted by Pennsylvania's anti-slavery laws and jobs afforded by the city's expanding commercial economy. The founding of the church also highlights the malleable character of American religion at this time; the ways religious groups became rallying points for the disenfranchised, the poor, and the upwardly mobile; and the speed and confidence with which Americans created and re-created ecclesiastical structures and enterprises. Despite the significance of this early black church, historians have not known the identities of the many black Philadelphians who became Methodists in the late eighteenth century, either those joining Allen's *I want to thank Richard Dunn, Gary Nash, and Jean Soderlund for their thoughtful comments, and Brian McCloskey, St. George's United Methodist Church, Philadelphia 1 Richard Allen, The Life Experience and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev Rtchard Allen (Reprint edition, Nashville, TN, 1960) My description of the black community in late eighteenth-century Philadelphia is based on Gary B Nash, "Forging Freedom The Eman- cipation Experience in the Northern Seaport Cities, 1775-1820" in Ira Berlin and Ronald Hoffman, eds., Slavery and Freedom tn the Age of the American Revolution, Perspectives on the American Revolution (Charlottesville, VA, 1983), 3-48. -

Rev. John Dickins by Charles Hargens, Based on an Eighteenth Century Engraving

A 1961 Painting of Rev. John Dickins by Charles Hargens, based on an eighteenth century engraving. Rev. John Dickins Outstanding Early Methodist Leader Rev. Dr. Frederick E. Maser (1989) Editor’s Note: Frederick E. Maser (1908-2002) was a member of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference for nearly 70 years. A well-known authority on early Methodism, he authored a number of books, including The Dramatic Story of Early American Methodism (1965) and The Story of John Wesley’s Sisters, or Seven Sisters in Search of Love (1988). The following paper was given as a speech on March 28, 1989 for the 200th anniversary meeting of the United Methodist Publishing House, held at St. George’s. The paper has not been published previously, though Dr. Maser’s findings on John Dickins’ son, Asbury, were outlined in his “Discovery” column, in the April 1989 issue of Methodist History. Dr. Maser’s work has been adapted for publication; additional materials have been added by the editor. One of the best educated and finest preachers in early American Methodism, John Dickins has never received his just dues from historians or other church luminaries. Despite his tremendous impor- tance in early Methodism, no life of Dickins has ever been written, and only passing references are made to him in Methodist histories. The most complete portrayal of the man is found in James Pilkington’s 1968 History of the Methodist Publishing House.1 I would like to share a few words about this outstanding early Methodist leader. John Dickins was born in London in 1747. The exact date is unknown, and he, himself wrote in the family Bible, now in possession of the Publishing House: John Dickins was born, (as he supposed) August 24th, 1747. -

Beginnings of a Black Theology and Its Social Impact Black Theology Was the Stream of African Theology That First Developed in America As a Layman Philosophy

Beginnings of a Black Theology and its Social Impact Black Theology was the stream of African Theology that first developed in America as a layman philosophy. For African Americans, the Bible at that time was the main source of information on Africa. The Psalm 68:31 served as the basis for the construction of an entire ideology of “Ethiopia” with which they meant, Africa. Out of it, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen composed: "May he who hath arisen to plead our cause, and engaged you as volunteers in the service, add to your numbers until the princes shall come from Egypt and Ethiopia stretch out her hand unto God.”1 This entire complex of beliefs and attitudes towards Africa, missions and the Back-to Africa impetus was very much incarnated in the person and work of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1834- 1915). In 1851, he joined the Methodist Church where he was later assigned deacon and elder and even, bishop. When Turner heard a speech of Crummell, this marked a turning point in his young life. But he first started a military and political career in the States until appointed chaplain by President Abraham Lincoln and later elected twice into the House of Representatives in Georgia. Here, he and other Blacks were prohibited from taking their seats.2 The ideas of African American missionary work in Africa and the return to this continent as the only way for Blacks to find justice; became Turner’s motivating force. He called for reparations for the years of slavery in order to finance the repatriation. -

Corson Letter

Behind the Scenes: A Document Concerning the 1968 Union Editor’s Introduction by Milton Loyer, 2004 What you are about to read is such an amazing piece of United Methodist memorabilia that it merits a special introduction. In this issue of The Chronicle devoted to material to relating to the various denominational separations and unions that have resulted in the United Methodist Church, this article stands alone in its significance beyond the Central Pennsylvania Conference – not only because of its content and its authorship, but also because of its apparent rarity and the possible “disappearance” of the document to which it refers. The Central Pennsylvania Conference archives, as most other United Methodist depositories, possesses 3 versions of the Plan of Union for the proposed 1968 union between the Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren denominations. They may be described as follows. (1) A small booklet with 3 parts (historical statement, enabling legislation, constitution) prepared for the April 1964 Methodist and October 1966 EUB General Conferences. (2) A large book with 4 parts (constitution, doctrinal statements and general rules, social principals, organization and administration) prepared for the November 1966 General Conferences in Chicago. (3) A slightly modified version of #2 prepared for the 1968 Uniting Session in Dallas. Apparently there was an earlier Plan of Union version that raised a few eyebrows because among other things it proposed (as a Methodist-EUB compromise) that the episcopal appointment of district superintendents be subject to approval by the annual conference [article IX under Episcopal Supervision]. The article that follows is a November 1963 reaction paper to that Plan by Bishop Fred Pierce Corson. -

On Absalom and Freedom February 17, 2019: the Sixth Sunday After the Epiphany the Rev. Emily Williams Guffey, Christ Church Detroit Luke 6:17-26

On Absalom and Freedom February 17, 2019: The Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany The Rev. Emily Williams Guffey, Christ Church Detroit Luke 6:17-26 Yesterday I was at the Cathedral along with several of you for the Feast of Blessed Absalom Jones, who was the first black person to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Absalom Jones had been born into slavery; he was separated from his family at a very young age, when his master sold his mother and all of his siblings, and took only Absalom along with him to a new city--to Philadelphia--where Absalom worked in the master’s store as a slave. The master did allow Absalom to go to a night school there in Philadelphia for enslaved people, and there Absalom learned to read; he learned math; he learned how to save what he could along the way. He married a woman named Mary and, saving his resources, was able to purchase her freedom. He soon saved enough to purchase his own freedom as well, although his master did not permit it. It would be years until his master finally allowed Absalom to purchase his own freedom. And when he did, Absalom continued to work in the master’s store, receiving daily wages. It was also during this time that Absalom came to attend St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Since Methodism had grown as a form of Anglicanism back in England, this was a time before the Methodist Church had come into its own denomination distinct from the Episcopal Church. -

History of the M.E. Church, Vol. Ii

WESLEYAN HERITAGE Library M. E. Church History HISTORY OF THE M.E. CHURCH, VOL. II By Abel Stevens, LL.D. “Follow peace with all men, and holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord” Heb 12:14 Spreading Scriptural Holiness to the World Wesleyan Heritage Publications © 1998 HISTORY of the METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH in the United States of America By Abel Stevens, LL.D., Author of "The History of the Religious Movement of the Eighteenth Century called Methodism," etc. VOLUME II The Planting and Training of American Methodism New York: Published By Carlton & Porter, 200 Mulberry-Street 1868 Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1861, by Carlton & Porter, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New-York HISTORY of the METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH By Abel Stevens VOLUME II The Planting and Training of American Methodism CONTENTS VOLUME II -- BOOK II -- CHAPTER VI CONFERENCES AND PROGRESS FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR TO THE ORGANIZATION OF THE METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH Annual Conferences before the Organization of the Church -- Their Character and Powers -- Philadelphia Session of 1775 -- Important Success -- John Cooper -- Robert Lindsay -- William Glendenning -- William Duke -- John Wade -- Daniel Ruff at Abbott's Family Altar -- Edward Dromgoole -- First Baltimore Session, 1776 -- Its Character -- Freeborn Garrettson joins it -- Great Prosperity -- Methodism tends Southward -- Nicholas Watters -- James Foster -- Isham Tatum -- Francis Poythress -- Richard -

All Rights Reserved by HDM for This Digital Publication Copyright 2000 Holiness Data Ministry

All Rights Reserved By HDM For This Digital Publication Copyright 2000 Holiness Data Ministry Duplication of this CD by any means is forbidden, and copies of individual files must be made in accordance with the restrictions stated in the B4Ucopy.txt file on this CD. * * * * * * * THE FIRST M. E. CHURCH ELDERS Compiled & Edited By Duane V. Maxey * * * * * * * Digital Edition 02/03/2000 By Holiness Data Ministry * * * * * * * INTRODUCTION This compilation presents biographical sketches of the First Ordained Elders of the Methodist Episcopal Church -- elected to this office at the Christmas Conference of 1784 when the Church was organized. Some of these first Elders were ordained at that conference; some were ordained following it. While their history does not eclipse the 19 to 24 years of American Methodist history prior to their ordination, it does tell us much about the M. E. Church at the birth of its organization. As with some leaders in other organizations, not all of this group turned out for the best:-- one especially fell to horrible depths, and another created a major split from the M. E. Church, but most accounts will tell a better story and can be a source of real inspiration to the reader. These compilations were created from the writings of various different Early Methodist historians and biographers, the four most used sources being the writings of Nathan Bangs, John Lednum, Abel Stevens, and Ezra Squier Tipple. All of the material for them was gathered from digital publications found in our HDM Digital Library. I do not claim to be the author, but simply the compiler and editor. -

History of Religions in Freehold Township

HISTORY OF RELIGIONS IN FREEHOLD TOWNSHIP Compiled By Father Edward Jawidzik of St. Robert Bellarmine Catholic Church For Freehold Township Historic Preservation Commission Compiled In 2003 (Updated 2016) BETHEL AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH 3 WATERWORKS RD. PO BOX 541 FREEHOLD, N.J. 07728 PHONE 732-462-0826 FAX 732-462-7015 HISTORY Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in 1867. A new structure was completed in 1988. The church was relocated to its present location. Bethel Church was an Episcopal form of church government where bishops of the African Methodist Episcopal Church appoint pastors. It is a worldwide church denomination with congregations in South America, Europe, Africa, Canada, Bermuda, The Caribbean Islands and the United States. Founded In 1787 By Rev. Richard Allen. This first leader was a former slave. The African Methodist Episcopal Church is divided into 19 Episcopal Districts. It was under the pastoral leadership of Rev. Malcolm S. Steele that Bethel experienced its greatest progress, development and growth. Rev. Steele was appointed to Bethel in 1966 and served until his retirement in 2000. COLTS NECK REFORMED CHURCH 72 ROUTE 537 W. P.O. BOX 57 COLTS NECK, N.J. 07722 PHONE 732-462-4555 FAX 732-866-9545 WEBSITE: http://www.cnrc.info--email: [email protected] HISTORY The First Reformed Protestant Church of Freehold, now known as Old Brick Reformed Church of Marlboro and was founded In 1699. Preaching in the area that is now Colts Neck; however was done in homes, barns and schoolhouses for the next 150 Years. The Colts Neck Reformed Church was organized as a sister congregation of the Freehold Church on Tuesday, April 22, 1856. -

Remembering John Harper, Dr. Joe Hale

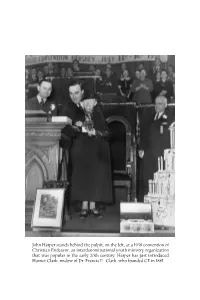

John Harper stands behind the pulpit, on the left, at a 1938 convention of Christian Endeavor, an interdenominational youth ministry organization that was popular in the early 20th century. Harper has just introduced Harriet Clark, widow of Dr. Francis E. Clark, who founded CE in 1881. Remembering John Harper Leading Layman of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference Dr. Joe Hale Editor’s Note: For 25 years, Dr. Joe Hale served as General Secretary of the World Methodist Council. Since his retirement in 2001, he has lived in Waynesville, North Carolina. We are grateful for his willingness to contribute this article. John R. Harper was well known, not only in the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference, but across the United Methodist Church. He was active at every level of his church and denomination. A delegate to Jurisdictional and General Conferences, he also served on the General Council on Finance and Administration. He was a leader in Simpson United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, where for many years he was the church school superintendent. After moving to Langhorne, he, along with Dr. Charles Yrigoyen, Sr., organized evening worship services for the Attleboro retirement community. John was a worker and supporter of Christian Endeavor from his youth, and on one occasion was responsible for Richard Nixon addressing a large Christian Endeavor conference. In 1961, he was a member of the organizing committee for the first Billy Graham Crusade in Philadelphia. John also served as an officer of both the Sunday School Union and the YMCA. He was the first lay leader of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference, having been elected to that role in its predecessor Philadelphia Conference in 1962, and serving until 1971. -

United Methodist Bishops Page 17 Historical Statement Page 25 Methodism in Northern Europe & Eurasia Page 37

THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA BOOK of DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2009 Copyright © 2009 The United Methodist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may reproduce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Northern Europe & Eurasia Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2009. Copyright © 2009 by The United Method- ist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. Used by permission.” Requests for quotations that exceed 1,000 words should be addressed to the Bishop’s Office, Copenhagen. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Name of the original edition: “The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church 2008”. Copyright © 2008 by The United Methodist Publishing House Adapted by the 2009 Northern Europe & Eurasia Central Conference in Strandby, Denmark. An asterisc (*) indicates an adaption in the paragraph or subparagraph made by the central conference. ISBN 82-8100-005-8 2 PREFACE TO THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA EDITION There is an ongoing conversation in our church internationally about the bound- aries for the adaptations of the Book of Discipline, which a central conference can make (See ¶ 543.7), and what principles it has to follow when editing the Ameri- can text (See ¶ 543.16). The Northern Europe and Eurasia Central Conference 2009 adopted the following principles. The examples show how they have been implemented in this edition.