CSCHS News Spring/Summer 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming Chief Justice: the Nomination and Confirmation Of

Becoming Chief Justice: A Personal Memoir of the Confirmation and Transition Processes in the Nomination of Rose Elizabeth Bird BY ROBERT VANDERET n February 12, 1977, Governor Jerry Brown Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office. It was an announced his intention to nominate Rose exciting opportunity: I would get to assist in the trials of OElizabeth Bird, his 40-year-old Agriculture & criminal defendants as a bar-certified law student work- Services Agency secretary, to be the next Chief Justice ing under the supervision of a public defender, write of California, replacing the retiring Donald Wright. The motions to suppress evidence and dismiss complaints, news did not come as a surprise to me. A few days earlier, and interview clients in jail. A few weeks after my job I had received a telephone call from Secretary Bird asking began, I was assigned to work exclusively with Deputy if I would consider taking a leave of absence from my posi- Public Defender Rose Bird, widely considered to be the tion as an associate at the Los Angeles law firm, O’Mel- most talented advocate in the office. She was a welcom- veny & Myers, to help manage her confirmation process. ing and supportive supervisor. That confirmation was far from a sure thing. Although Each morning that summer, we would meet at her it was anticipated that she would receive a positive vote house in Palo Alto and drive the short distance to the from Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, who would San Jose Civic Center in Rose’s car, joined by my co-clerk chair the three-member for the summer, Dick Neuhoff. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Law News UC Hastings Archives and History 11-1-1984 Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln Recommended Citation UC Hastings College of the Law, "Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2" (1984). Hastings Law News. Book 132. http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln/132 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the UC Hastings Archives and History at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law News by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hastings College of the Law Nov. Dec. 1984 SUPREME COURT'S SEVEN DEADLY SINS "To construe and build the law - especially constitutional law - is 4. Inviting the tyranny of small decisions: When the Court looks at a prior decision to choose the kind of people we will be," Laurence H. Tribe told a and decides it is only going a little step further a!ld therefore doing no harm, it is look- ing at its feet to see how far it has gone. These small steps sometimes reduce people to standing-room-only audience at Hastings on October 18, 1984. Pro- things. fessor Tribe, Tyler Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard, gave 5. Ol'erlooking the constitutil'e dimension 0/ gOl'ernmental actions and what they the 1984 Mathew O. Tobriner Memorial Lecture on the topic of "The sa)' about lIS as a people and a nation: Constitutional decisions alter the scale of what Court as Calculator: the Budgeting of Rights." we constitute, and the Court should not ignore this element. -

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O'connor College of Law Arizona

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona 85287-7906 (480) 965-2125 http://www.law.asu.edu/HomePages/Ellman/ EDUCATION: J.D. Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California, Berkeley (June, 1973). Head Article Editor, California Law Review. Order of the Coif. M.A. Psychology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois (October, 1969). National Institute of Mental Health Fellowship. B.A. Psychology, Reed College, Portland, Oregon (May, 1967). Nominated, Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS: Associate Justice William O. Douglas United States Supreme Court, 1973-74. Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, California Supreme Court, 1/31/72 through 6/5/72. PERMANENT AND VISITING AFFILIATIONS: 5/81 to Present: Professor of Law and (since 2001) Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar, Arizona State University. 9/2003 to Present Affiliate Faculty Member, Center for Child and Youth Policy, University of California at Berkeley. 9/2010 to 12/2010 Visiting Fellow Commoner, Trinity College, University of Cambridge 6/2007 to 12/2007 Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Law and Society, U.C. Berkeley 8/2006 to 12/2006 Visiting Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School 10/95 to 5/2001 Chief Reporter, American Law Institute, for Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution. Justice R. Ammi Cutter Reporter, from June, 1998. (Reporter, 10/92-10/95; Associate Reporter, 2/91 to 10/92). 8/2005 to 12/2005 Visiting Scholar, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley 8/2004 to 12/2004 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2003 to 12/2003 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2000 to 5/2002 Visiting Professor, Hastings College of The Law, University of California. -

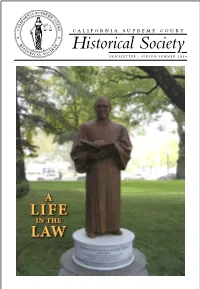

Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk by Jacqueline R

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2014 A Life in The LAw The Longest-Serving Justice Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk By Jacqueline R. Braitman and Gerald F. Uelmen* undreds of mourners came to Los Angeles’ future allies. With rare exceptions, Mosk maintained majestic Wilshire Boulevard Temple in June of cordial relations with political opponents throughout H2001. The massive, Byzantine-style structure his lengthy career. and its hundred-foot-wide dome tower over the bustling On one of his final days in office, Olson called Mosk mid-city corridor leading to the downtown hub of finan- into his office and told him to prepare commissions to cial and corporate skyscrapers. Built in 1929, the historic appoint Harold Jeffries, Harold Landreth, and Dwight synagogue symbolizes the burgeoning pre–Depression Stephenson to the Superior Court, and Eugene Fay and prominence and wealth of the region’s Mosk himself to the Municipal Court. Jewish Reform congregants, includ- Mosk thanked the governor profusely. ing Hollywood moguls and business The commissions were prepared and leaders. Filing into the rows of seats in the governor signed them, but by then the cavernous sanctuary were two gen- it was too late to file them. The secre- erations of movers and shakers of post- tary of state’s office was closed, so Mosk World War II California politics, who locked the commissions in his desk and helped to shape the course of history. went home, intending to file them early Sitting among less recognizable faces the next morning. -

The California Recall History Is a Chronological Listing of Every

Complete List of Recall Attempts This is a chronological listing of every attempted recall of an elected state official in California. For the purposes of this history, a recall attempt is defined as a Notice of Intention to recall an official that is filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. 1913 Senator Marshall Black, 28th Senate District (Santa Clara County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Herbert C. Jones elected successor Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Failed to qualify for the ballot 1914 Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Edwin I. Wolfe elected successor Senator James C. Owens, 9th Senate District (Marin and Contra Costa counties) Qualified for the ballot, officer retained 1916 Assemblyman Frank Finley Merriam Failed to qualify for the ballot 1939 Governor Culbert L. Olson Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Citizens Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1940 Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1960 Governor Edmund G. Brown Filed by Roderick J. Wilson Failed to qualify for the ballot 1 Complete List of Recall Attempts 1965 Assemblyman William F. Stanton, 25th Assembly District (Santa Clara County) Filed by Jerome J. Ducote Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman John Burton, 20th Assembly District (San Francisco County) Filed by John Carney Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman Willie L. -

Contents SCHOOL of LAW

UCLA Contents SCHOOL OF LAW THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCHOOL OF LAW V OL. 25–NO. 1 FALL 2001 2 A MESSAGE FROM DEAN JONATHAN D. VARAT UCLA Magazine 2002 Regents of the University of California 4 THE JUDGES OF UCLA LAW UCLA School of Law 12 JUDGES AS ALTRUISTIC HIERARCHS Box 951476 Sidebars: Los Angles, California 90095-1476 Externships for Students in Judges’ Chambers Faculty who have clerked Jonathan D. Varat, Dean Kerry A. Bresnahan ‘89, Assistant Dean, External Affairs David Greenwald, Editorial Director for Marketing and 16 FACULTY Communications Services, UCLA Recent Publications by the Faculty Regina McConahay, Director of Communications, Kenneth Karst gives keynote address at the Jefferson Memorial Lecture UCLA School of Law William Rubenstein wins the Rutter Award Francisco A. Lopez, Manager of Publications and Graphic Grant Nelson honored with the University Distinguished Teaching Award Design Donna Colin, Director of Major Gifts Gary Blasi receives two awards Charles Cannon, Director of Annual and Special Giving Law Day Shines on Michael Asimow and Paul Bergman Kristine Werlinich, Director of Alumni Relations Teresa Estrada-Mullaney ‘77 and Laura Gomez conduct workshop on The Castle Press, Printer Institutional Racism Design,Tricia Rauen, Treehouse Design and Betty Adair, The Castle Press Photographers,Todd Cheney, Regina McConahay, Scott 25 MAJOR GIFTS Leadership in the Development office: Quintard, Bill Short and Mary Ann Stuehrmann 1 Assistant Dean Kerry Bresnahan ‘89 UCLA School of Law Board of Advisors Director of Major Gifts Donna Colin Michael Masin ’69, Co-Chair Director of Annual and Special Giving Charles Cannon Kenneth Ziffren ’65, Co-Chair William M. -

Oral History Interview with Frank C. Newman

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with FRANK C. NEWMAN Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley, 1946-present Justice, California Supreme Court, 1977--1983 January 24, Februrary 7, March 30, November 28, 1989; April 16, May 7, June 10, June 18, June 24, July 11, 1991 Berkeley, California By Carole Hicke Regional Oral History Office University of California, Berkeley RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATIONS This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 201 N. Sunrise Avenue Roseville, California 95661 or Regional Oral History Office 486 Library University of California Berkeley, California 94720 The request should include information of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Frank C. Newman, Oral History Interview, Conducted 1989 and 1991 by Carole Hicke, Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. California State Archives (916) 773-3000 Office of the Secretary of State 201 No. Sunrise Avenue (FAX) 773-8249 March Fong Eu Sacramento, California 95661 PREFACE On September 25, 1985, Governor George Deukmejian signed into law A.B. 2104 (Chapter 965 of the Statutes of 1985). This legislation established, under the administration of the California State Archives, a State Government Oral History Program "to provide through the use of oral history a continuing documentation of state policy development as reflected in California's legislative and executive history." The following interview is one of a series of oral histories undertaken for inclusion in the state program. -

“The Rise and Fall of Rose Bird” Patrick K. Brown

THE RISE AND FALL OF ROSE BIRD A Career Killed by the Death Penalty by Patrick K. Brown © M.A. Program, California State University, Fullerton Justice Rose Bird, in the sixty-one capital cases heard by the California Supreme Court while she served as its Chief Justice, never voted to uphold a death sentence. Nearly every obituary written after her December 4, 1999 death made reference to this fact, noting that her votes on capital punishment led to her ouster from office in the election of 1986. This was true, both in reports from neutral observers and those written by organizations and individuals that could be characterized as sympathetic to her views. The New York Times, on December 6, 1999, wrote “[a]fter the death penalty was reinstated in California in the late 1970's, Judge Bird never upheld a death sentence, voting to vacate such sentences 61 times. She survived repeated efforts to recall her, but she was ousted after Governor George Deukmejian, a Republican, led an aggressive campaign against her. To this day, Ms. Bird’s name remains a kind of reflexive shorthand in California for ‘soft-on-crime liberal’.”1 In the ACLU News, published by the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, actor Mike Farrell, of M.A.S.H. television series fame, and President of Death Penalty Focus, in a tribute to Justice Bird, wrote: Virtually without exception, obituaries of former California Chief Justice Rose Bird attribute her 1986 electoral defeat to her unwavering opposition to the death penalty. In fact, her purported opposition to the death penalty was not the motivation for conservatives who set out to remove the state’s first female 1 Todd S. -

The Law of Abolition Kevin M

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 107 Article 1 Issue 4 The Death Penalty's Numbered Days? Fall 2017 The Law of Abolition Kevin M. Barry Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin M. Barry, The Law of Abolition, 107 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 521 (2017). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol107/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. BARRY 10/10/17 5:42 PM 0091-4169/17/10704-0521 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 107, No. 4 Copyright © 2017 by Kevin M. Barry Printed in U.S.A. THE LAW OF ABOLITION KEVIN M. BARRY* Three themes have characterized death penalty abolition throughout the Western world: a sustained period of de facto abolition; an understanding of those in government that the death penalty implicates human rights; and a willingness of those in government to defy popular support for the death penalty. The first two themes are present in the U.S.; what remains is for the U.S. Supreme Court to manifest a willingness to act against the weight of public opinion and to live up to history’s demands. When the Supreme Court abolishes the death penalty, it will be traveling a well-worn road. This Essay gathers, for the first time and all in one place, the opinions of judges who have advocated abolition of the death penalty over the past half-century, and suggests, through this “law of abolition,” what a Supreme Court decision invalidating the death penalty might look like. -

Chapter Five Gay Marriage

The Domino Effect How Strategic Moves for Gay Rights, Singles’ Rights and Family Diversity Have Touched the Lives of Millions Memoirs of an Equal Rights Advocate by Thomas F. Coleman Spectrum Institute Press Copyright © by Thomas F. Coleman All rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States ISBN 13: 978-0-9825158-0-8 www.dominoeffectbook.com Spectrum Institute P.O. Box 11030 Glendale, CA 91226 (818) 230-5156 [email protected] With gratitude to my life mate and spouse, Michael A. Vasquez, for supporting and helping me over the last three decades as I have advocated for many of the cases and causes described in this book And with appreciation to family members, friends, and colleagues, who have stood by me and worked with me since the early 1970s to achieve equal justice under law for all segments of society CONTENTS About the Author ...................................................... I Acknowledgments .............................................................. v Preface .................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Birds of a Feather ................................ 5 Young gay law students shake up the legal system Chapter Two: From Defensive to Offensive ........... 20 Ending judicial bias and police harassment are not easy tasks Chapter Three: Working with Governors .............. 41 Refocusing attention to the executive branch of government pays off Chapter Four: Redefining “Family” ........................ 70 Moving beyond tradition is necessary in a changing society Chapter Five: Gay Marriage ...................................... 97 Matrimony is personally appealing but politically questionable Chapter Six: Singles’ Rights ........................................ 120 Calling attention to the needs of single people yields mixed results Chapter Seven: Not in My Apartment ....................... 140 Successfully fighting the religious intolerance of landlords requires perseverance Chapter Eight: In Sickness and in Death ................ -

CSCHS Review Spring/Summer 2021

California Supreme Court Historical Society Review SPRING/SUMMER 2021 What Did We Learn? California Courts’ Response to the 1918 Influenza Epidemic People waiting in line to get flu masks to avoid the spread of Spanish influenza. Montgomery Street in San Francisco, 1918. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. What Did We Learn from the California Courts’ Response to the Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1919? BY JENNIFER KING he California judiciary’s response to the appellate districts and 58 trial courts confronted dif- COVID-19 pandemic was swift and thought- ferent impacts. As a result, the Judicial Council moved Tful. Mindful of the need to balance community away from statewide orders and relied on flexible adviso- health and safety needs with individual civil and con- ries and orders unique to each court to address the pan- stitutional rights and liberties, the Judicial Council of demic. By December 2020, Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye California, chaired by California Chief Justice Tani G. had signed 353 emergency orders to assist trial courts Cantil-Sakauye, issued emergency measures beginning in their COVID-19 management efforts.3 For example, in March 2020.1 Following the first statewide stay-at- a January 2021 order concerning Los Angeles County home order, the Judicial Council extended several stat- provided flexibility for the locations of holding criminal utory deadlines, suspended jury trials for 60 days and hearings and extended a number of statutory deadlines expanded the use of technology to conduct proceedings in criminal and juvenile dependency cases, whereas Janu- remotely.2 ary 2021 orders in smaller counties such as Lake County As the pandemic evolved, so did the Judicial Coun- and Placer County provided only a 30-day extension for cil’s response.