The Law of Abolition Kevin M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

Reaching for Freedom: Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 Reaching for Freedom: Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts Emily V. Blanck College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blanck, Emily V., "Reaching for Freedom: Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626189. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-yxr6-3471 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACHING FOR FREEDOM Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts b y Emily V. Blanck 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Emily Blanck Approved, April 1998 Leisa Mever (3Lu (Aj/K) Kimb^ley Phillips ^ KlU MaU ________________ Ronald Schechter ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As is the case in every such project, this thesis greatly benefitted from the aid of others. -

CSCHS News Spring/Summer 2015

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2015 Righting a WRong After 125 Years, Hong Yen Chang Becomes a California Lawyer Righting a Historic Wrong The Posthumous Admission of Hong Yen Chang to the California Bar By Jeffrey L. Bleich, Benjamin J. Horwich and Joshua S. Meltzer* n March 16, 2015, the 2–1 decision, the New York Supreme California Supreme Court Court rejected his application on Ounanimously granted Hong the ground that he was not a citi- Yen Chang posthumous admission to zen. Undeterred, Chang continued the State Bar of California. In its rul- to pursue admission to the bar. In ing, the court repudiated its 125-year- 1887, a New York judge issued him old decision denying Chang admission a naturalization certificate, and the based on a combination of state and state legislature enacted a law per- federal laws that made people of Chi- mitting him to reapply to the bar. The nese ancestry ineligible for admission New York Times reported that when to the bar. Chang’s story is a reminder Chang and a successful African- of the discrimination people of Chi- American applicant “were called to nese descent faced throughout much sign for their parchments, the other of this state’s history, and the Supreme students applauded each enthusiasti- Court’s powerful opinion explaining cally.” Chang became the only regu- why it granted Chang admission is Hong Yen Chang larly admitted Chinese lawyer in the an opportunity to reflect both on our United States. state and country’s history of discrimination and on the Later Chang applied for admission to the Califor- progress that has been made. -

Becoming Chief Justice: the Nomination and Confirmation Of

Becoming Chief Justice: A Personal Memoir of the Confirmation and Transition Processes in the Nomination of Rose Elizabeth Bird BY ROBERT VANDERET n February 12, 1977, Governor Jerry Brown Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office. It was an announced his intention to nominate Rose exciting opportunity: I would get to assist in the trials of OElizabeth Bird, his 40-year-old Agriculture & criminal defendants as a bar-certified law student work- Services Agency secretary, to be the next Chief Justice ing under the supervision of a public defender, write of California, replacing the retiring Donald Wright. The motions to suppress evidence and dismiss complaints, news did not come as a surprise to me. A few days earlier, and interview clients in jail. A few weeks after my job I had received a telephone call from Secretary Bird asking began, I was assigned to work exclusively with Deputy if I would consider taking a leave of absence from my posi- Public Defender Rose Bird, widely considered to be the tion as an associate at the Los Angeles law firm, O’Mel- most talented advocate in the office. She was a welcom- veny & Myers, to help manage her confirmation process. ing and supportive supervisor. That confirmation was far from a sure thing. Although Each morning that summer, we would meet at her it was anticipated that she would receive a positive vote house in Palo Alto and drive the short distance to the from Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, who would San Jose Civic Center in Rose’s car, joined by my co-clerk chair the three-member for the summer, Dick Neuhoff. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 6-21-2018 The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected] Mary Sarah Bilder Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Profession Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Laurel Davis and Mary Sarah Bilder. "The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist." (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Library of Robert Morris, Antebellum Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist∗ Laurel Davis** and Mary Sarah Bilder*** Contact information: Boston College Law Library Attn: Laurel Davis 885 Centre St. Newton, MA 02459 Abstract (50 words or less): This article analyzes the Robert Morris library, the only known extant, antebellum African American-owned library. The seventy-five titles, including two unique pamphlet compilations, reveal Morris’s intellectual commitment to full citizenship, equality, and participation for people of color. The library also demonstrates the importance of book and pamphlet publication as means of community building among antebellum civil rights activists. -

Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Law News UC Hastings Archives and History 11-1-1984 Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln Recommended Citation UC Hastings College of the Law, "Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2" (1984). Hastings Law News. Book 132. http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln/132 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the UC Hastings Archives and History at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law News by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hastings College of the Law Nov. Dec. 1984 SUPREME COURT'S SEVEN DEADLY SINS "To construe and build the law - especially constitutional law - is 4. Inviting the tyranny of small decisions: When the Court looks at a prior decision to choose the kind of people we will be," Laurence H. Tribe told a and decides it is only going a little step further a!ld therefore doing no harm, it is look- ing at its feet to see how far it has gone. These small steps sometimes reduce people to standing-room-only audience at Hastings on October 18, 1984. Pro- things. fessor Tribe, Tyler Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard, gave 5. Ol'erlooking the constitutil'e dimension 0/ gOl'ernmental actions and what they the 1984 Mathew O. Tobriner Memorial Lecture on the topic of "The sa)' about lIS as a people and a nation: Constitutional decisions alter the scale of what Court as Calculator: the Budgeting of Rights." we constitute, and the Court should not ignore this element. -

“White”: the Judicial Abolition of Native Slavery in Revolutionary Virginia and Its Racial Legacy

ABLAVSKY REVISED FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/13/2011 1:24 PM COMMENT MAKING INDIANS “WHITE”: THE JUDICIAL ABOLITION OF NATIVE SLAVERY IN REVOLUTIONARY VIRGINIA AND ITS RACIAL LEGACY † GREGORY ABLAVSKY INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1458 I. THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF INDIAN SLAVERY IN VIRGINIA .............. 1463 A. The Origins of Indian Slavery in Early America .................. 1463 B. The Legal History of Indian Slavery in Virginia .................. 1467 C. Indians, Africans, and Colonial Conceptions of Race ........... 1473 II. ROBIN V. HARDAWAY, ITS PROGENY, AND THE LEGAL RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF SLAVERY ........................................... 1476 A. Indian Freedom Suits and Racial Determination ...................................................... 1476 B. Robin v. Hardaway: The Beginning of the End ................. 1480 1. The Statutory Claims ............................................ 1481 2. The Natural Law Claims ....................................... 1484 3. The Outcome and the Puzzle ............................... 1486 C. Robin’s Progeny ............................................................. 1487 † J.D. Candidate, 2011; Ph.D. Candidate, 2014, in American Legal History, Univer- sity of Pennsylvania. I would like to thank Sarah Gordon, Daniel Richter, Catherine Struve, and Michelle Banker for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this Comment; Richard Ross, Michael Zuckerman, and Kathy Brown for discussions on the work’s broad contours; and -

Black Abolitionists Used the Terms “African,” “Colored,” Commanding Officer Benjamin F

$2 SUGGESTED DONATION The initiative of black presented to the provincial legislature by enslaved WHAT’S IN A NAME? Black people transformed a war men across greater Boston. Finally, in the early 1780s, Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman (Image 1) to restore the Union into of Sheffield and Quock Walker of Framingham Throughout American history, people Abolitionists a movement for liberty prevailed in court. Although a handful of people of African descent have demanded and citizenship for all. of color in the Bay State still remained in bondage, the right to define their racial identity (1700s–1800s) slavery was on its way to extinction. Massachusetts through terms that reflect their In May 1861, three enslaved black men sought reported no slaves in the first census in 1790. proud and complex history. African refuge at Union-controlled Fort Monroe, Virginia. Americans across greater Boston Rather than return the fugitives to the enemy, Throughout the early Republic, black abolitionists used the terms “African,” “colored,” Commanding Officer Benjamin F. Butler claimed pushed the limits of white antislavery activists and “negro” to define themselves the men as “contrabands of war” and put them to who advocated the colonization of people of color. before emancipation, while African work as scouts and laborers. Soon hundreds of In 1816, a group of whites organized the American Americans in the early 1900s used black men, women, and children were streaming Colonization Society (ACS) for the purpose of into the Union stronghold. Congress authorized emancipating slaves and resettling freedmen and the terms “black,” “colored,” “negro,” the confiscation of Confederate property, freedwomen in a white-run colony in West Africa. -

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O'connor College of Law Arizona

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona 85287-7906 (480) 965-2125 http://www.law.asu.edu/HomePages/Ellman/ EDUCATION: J.D. Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California, Berkeley (June, 1973). Head Article Editor, California Law Review. Order of the Coif. M.A. Psychology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois (October, 1969). National Institute of Mental Health Fellowship. B.A. Psychology, Reed College, Portland, Oregon (May, 1967). Nominated, Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS: Associate Justice William O. Douglas United States Supreme Court, 1973-74. Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, California Supreme Court, 1/31/72 through 6/5/72. PERMANENT AND VISITING AFFILIATIONS: 5/81 to Present: Professor of Law and (since 2001) Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar, Arizona State University. 9/2003 to Present Affiliate Faculty Member, Center for Child and Youth Policy, University of California at Berkeley. 9/2010 to 12/2010 Visiting Fellow Commoner, Trinity College, University of Cambridge 6/2007 to 12/2007 Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Law and Society, U.C. Berkeley 8/2006 to 12/2006 Visiting Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School 10/95 to 5/2001 Chief Reporter, American Law Institute, for Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution. Justice R. Ammi Cutter Reporter, from June, 1998. (Reporter, 10/92-10/95; Associate Reporter, 2/91 to 10/92). 8/2005 to 12/2005 Visiting Scholar, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley 8/2004 to 12/2004 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2003 to 12/2003 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2000 to 5/2002 Visiting Professor, Hastings College of The Law, University of California. -

Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk by Jacqueline R

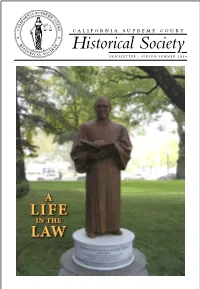

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2014 A Life in The LAw The Longest-Serving Justice Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk By Jacqueline R. Braitman and Gerald F. Uelmen* undreds of mourners came to Los Angeles’ future allies. With rare exceptions, Mosk maintained majestic Wilshire Boulevard Temple in June of cordial relations with political opponents throughout H2001. The massive, Byzantine-style structure his lengthy career. and its hundred-foot-wide dome tower over the bustling On one of his final days in office, Olson called Mosk mid-city corridor leading to the downtown hub of finan- into his office and told him to prepare commissions to cial and corporate skyscrapers. Built in 1929, the historic appoint Harold Jeffries, Harold Landreth, and Dwight synagogue symbolizes the burgeoning pre–Depression Stephenson to the Superior Court, and Eugene Fay and prominence and wealth of the region’s Mosk himself to the Municipal Court. Jewish Reform congregants, includ- Mosk thanked the governor profusely. ing Hollywood moguls and business The commissions were prepared and leaders. Filing into the rows of seats in the governor signed them, but by then the cavernous sanctuary were two gen- it was too late to file them. The secre- erations of movers and shakers of post- tary of state’s office was closed, so Mosk World War II California politics, who locked the commissions in his desk and helped to shape the course of history. went home, intending to file them early Sitting among less recognizable faces the next morning. -

The Lost History of Slaves and Slave Owners in Billerica” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 42, No

Christopher M. Spraker, “The Lost History of Slaves and Slave Owners in Billerica” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 42, No. 1 (Winter 2014). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.wsc.ma.edu/mhj. 108 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2014 The Boston Gazette ran the above advertisement on May 9, 1774, alerting readers that a slave owned by William Tompson, a prominent Billerica landowner, had run away. The text reads: Ran away from William Thompson of Billerica, on the 24th, a NegroMan named Caesar, about 5 Feet 7 Inches high, carried with him two Suits of Cloathes, homespun all Wool, light coloured, with white Lining and plain Brass Buttons, the other homespun Cotton and Linnen Twisted. Whoever takes up said Negro and secures him, or returns him to his Master, shall be handsomely rewarded, and all necessary Charges paid by JONATHAN STICKNEY. N. B. All Masters of Vessels and others, are cautioned from carrying off or concealing said Negro, as they would avoid the Penalty of the Law. 109 The Lost History of Slaves and Slave Owners in Billerica, Massachusetts, 1655-1790 CHRISTOPHER M.