ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL ______Volume 11 2000 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pouteria Sapota, Sapotaceae) from Southeastern Mexico: Its Putative Domestication Center

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 7-6-2019 Structure and genetic diversity in wild and cultivated populations of Zapote mamey (Pouteria sapota, Sapotaceae) from southeastern Mexico: its putative domestication center Jaime Martínez-Castillo Centro de Investigación Científica de ucatánY (CICY), [email protected] Nassib H. Blancarte-Jasso Centro de Investigación Científica de ucatánY (CICY) Gabriel Chepe-Cruz Centro de Investigación Científica de ucatánY (CICY) Noemí G. Nah-Chan Centro de Investigación Científica de ucatánY (CICY) Matilde M. Ortiz-García Centro de Investigación Científica de ucatánY (CICY) See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Martínez-Castillo, Jaime; Blancarte-Jasso, Nassib H.; Chepe-Cruz, Gabriel; Nah-Chan, Noemí G.; Ortiz- García, Matilde M.; and Arias, Renee S., "Structure and genetic diversity in wild and cultivated populations of Zapote mamey (Pouteria sapota, Sapotaceae) from southeastern Mexico: its putative domestication center" (2019). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 2200. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/2200 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Jaime Martínez-Castillo, Nassib H. -

ZAPOTE the Popular Name Represents Many Diverse Edible Fruits of Guatemala

Sacred Animals and Exotic Tropical Plants monzón sofía photo: by Dr. Nicholas M. Hellmuth and Daniela Da’Costa Franco, FLAAR Reports ZAPOTE The popular name represents many diverse edible fruits of Guatemala ne of the tree fruits raised by the Most zapotes have a soft fruit inside and Maya long ago that is still enjoyed a “zapote brown” covering outside (except today is the zapote. Although for a few that have other external colors). It Othere are several fruits of the same name, the is typical for Spanish nomenclature of fruits popular nomenclature is pure chaos. Some of and flowers to be totally confusing. Zapote is the “zapote” fruits belong to the sapotaceae a vestige of the Nahuatl (Aztec) word tzapotl. family and all are native to Mesoamerica. The first plant on our list, Manilkara But other botanically unrelated fruits are also zapote, is commonly named chicozapote. called zapote/sapote; some are barely edible This is one of the most appreciated edible (such as the zapotón). There are probably species because of its commercial value. It even other zapote-named fruits that are not is distributed from the southeast of Mexico, all native to Mesoamerica. especially the Yucatán Peninsula into Belize 60 Dining ❬ ANTIGUA and the Petén area, where it is occasionally now collecting pertinent information related an abundant tree in the forest. The principal to the eating habits of Maya people, and all products of these trees are the fruit; the the plants they used and how they used them latex, which is used as the basis of natural for food. -

Bird Responses to Shade Coffee Production

Animal Conservation (2004) 7, 169–179 C 2004 The Zoological Society of London. Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S1367943004001258 Bird responses to shade coffee production Cesar´ Tejeda-Cruz and William J. Sutherland Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Conservation, School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK (Received 2 June 2003; accepted 16 October 2003) Abstract It has been documented that certain types of shade coffee plantations have both biodiversity levels similar to natural forest and high concentrations of wintering migratory bird species. These findings have triggered a campaign to promote shade coffee as a means of protecting Neotropical migratory birds. Bird censuses conducted in the El Triunfo Biosphere reserve in southern Mexico have confirmed that shade coffee plantations may have bird diversity levels similar to, or higher than, natural forest. However, coffee and forest differed in species composition. Species with a high sensitivity to disturbance were significantly more diverse and abundant in primary ecosystems. Neotropical migratory birds, granivorous and omnivorous species were more abundant in disturbed habitats. Insectivorous bird species were less abundant only in shaded monoculture. Foraging generalists and species that prefer the upper foraging stratum were more abundant in disturbed habitats, while a decline in low and middle strata foragers was found there. Findings suggests that shade coffee may be beneficial for generalist species (including several migratory species), but poor for forest specialists. Although shade coffee plantations may play an important role in maintaining local biodiversity, and as buffer areas for forest patches, promotion of shade coffee may lead to the transformation of forest into shade coffee, with the consequent loss of forest species. -

TOUR REPORT Southwestern Amazonia 2017 Final

For the first time on a Birdquest tour, the Holy Grail from the Brazilian Amazon, Rondonia Bushbird – male (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S SOUTHWESTERN AMAZONIA 7 / 11 - 24 JUNE 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL What an impressive and rewarding tour it was this inaugural Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia. Sixteen days of fine Amazonian birding, exploring some of the most fascinating forests and campina habitats in three different Brazilian states: Rondonia, Amazonas and Acre. We recorded over five hundred species (536) with the exquisite taste of specialties from the Rondonia and Inambari endemism centres, respectively east bank and west bank of Rio Madeira. At least eight Birdquest lifer birds were acquired on this tour: the rare Rondonia Bushbird; Brazilian endemics White-breasted Antbird, Manicore Warbling Antbird, Aripuana Antwren and Chico’s Tyrannulet; also Buff-cheeked Tody-Flycatcher, Acre Tody-Tyrant and the amazing Rufous Twistwing. Our itinerary definitely put together one of the finest selections of Amazonian avifauna, though for a next trip there are probably few adjustments to be done. The pre-tour extension campsite brings you to very basic camping conditions, with company of some mosquitoes and relentless heat, but certainly a remarkable site for birding, the Igarapé São João really provided an amazing experience. All other sites 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com visited on main tour provided considerably easy and very good birding. From the rich east part of Rondonia, the fascinating savannas and endless forests around Humaitá in Amazonas, and finally the impressive bamboo forest at Rio Branco in Acre, this tour focused the endemics from both sides of the medium Rio Madeira. -

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

First Nesting Record of the Nest of a Slaty&Hyphen;Backed

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS J. RaptorRes. 34(2):148-150 ¸ 2000 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. FIRST NESTING RECORD OF THE NEST OF A SLATY-BACKED FOREST-FALCON (MJCRASTURMIRANDOLI•I) IN YASUNi NATtONAL PAm•, ECU•DOmAN AMAZON TJITTE DE VRIES AND CRISTIANMELO Departamentode Biologia, Pontifida Universidad Cat61ica del Ecuador, Apartado 17-01-2184, Quito, Ecuador KEY WORDS: Slaty-backedForest-Falcon; Micrastur miran- first falconwas smaller and probablythe male of the pair. dollei; first nestingrecord; stick nest;, Ecuad• After the male flew into the forest, the female walked to the nest and stood on the edge for 2-3 min before it The genus Micrasturconsists of six species,all having disappearedinto the forest at 1642 H. At 1732 H, the a furtive life in humid and wet forests in Central and female returned and perched in a tree 10 m from the South America (Hilty and Brown 1986, del Hoyo et al. nest and preened and cleaned its clawsas if it had just 1994). The Barred Forest-Falcon(M. ruficollis)and the eaten prey. At 1745 H, the female flew into the forest Collared Forest-Falcon(M. semitorquatus)are known to and did not return before we left at 1830 H. We con~ nest in tree cavities (Mader 1979, Thorstrom and Morales cluded that the birds we observedwere not Grey-bellied 1993, Thorstrom et al. 1990, Thorstrom et al. 1991, Thor- Hawks (Accipiterpoliogaster) because the female had a strom et al. 1992) but there is no information on the pure white belly and the facial area was notably yellow breeding of the PlumbeousForest-Falcon (M. -

Our Recent Bird Surveys

Breeding Birds Survey at Germantown MetroPark Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Accipiter cooperii hawk, Cooper's Corvus brachyrhynchos crow, American Accipiter striatus hawk, sharp shinned Cyanocitta cristata jay, blue Aegolius acadicus owl, saw-whet Dendroica cerulea warbler, cerulean Agelaius phoeniceus blackbird, red-winged Dendroica coronata warbler, yellow-rumped Aix sponsa duck, wood Dendroica discolor warbler, prairie Ammodramus henslowii sparrow, Henslow's Dendroica dominica warbler, yellow-throated Ammodramus savannarum sparrow, grasshopper Dendroica petechia warbler, yellow Anas acuta pintail, northern Dendroica pinus warbler, pine Anas crecca teal, green-winged Dendroica virens warbler, black-throated Anas platyrhynchos duck, mallard green Archilochus colubris hummingbird, ruby-throated Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Ardea herodias heron, great blue Dryocopus pileatus woodpecker, pileated Asio flammeus owl, short-eared Dumetella carolinensis catbird, grey Asio otus owl, long-eared Empidonax minimus flycatcher, least Aythya collaris duck, ring-necked Empidonax traillii flycatcher, willow Baeolphus bicolor titmouse, tufted Empidonax virescens flycatcher, Acadian Bombycilla garrulus waxwing, cedar Eremophia alpestris lark, horned Branta canadensis goose, Canada Falco sparverius kestrel, American Bubo virginianus owl, great horned Geothlypis trichas yellowthroat, common Buteo jamaicensis hawk, red-tailed Grus canadensis crane, sandhill Buteo lineatus hawk, red-shouldered Helmitheros vermivorus warbler, worm-eating -

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

Spondias Mombin Anacardiaceae L

Spondias mombin L. Anacardiaceae LOCAL NAMES Creole (gwo momben,gran monben,monben,monben fran); Dutch (hoeboe); English (mombin plum,yellow mombin,hog plum,yellow spanish plum); French (grand mombin,gros mombin,mombin jaune,prunier mombin,mombin franc); Fula (chali,chaleh,tali); Indonesian (kedongdong cina,kedongdong cucuk,kedongdong sabrang); Mandinka (ninkongo,ninkon,ningo,nemkoo); Portuguese (cajá,cajarana,caja- mirim,pau da tapera,taperreba,acaiba); Spanish (jojobán,circuela,ciruela,ciruelo,ciurela amarilla,balá,hobo,jobito,jobo blanco,jobo colorado,jobo corronchoso,jobo de puerco,jobo vano,ubo,jobo Spondias mombin slash (Joris de Wolf, gusanero); Wolof (nimkom,nimkoum,ninkon,ninkong) Patrick Van Damme, Diego Van Meersschaut) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Spondias mombin is a tree to 30 m high; bark greyish-brown, thick, rough, often deeply grooved, with blunt, spinelike projections; trunk with branches 2-10 m above ground level to form a spreading crown up to 15 m in diameter and forming an open or densely closed canopy, depending on the vigour of the individual; seedlings with deep taproot, probably persisting in mature tree, which also possesses a shallower root system near the surface. Leaves alternate, once pinnate with an odd terminal leaflet; stipules absent; rachis 30-70 cm long; leaflets 5-10 pairs, elliptic, 5-11 x 2-5 cm; Spondias mombin foliage (Joris de Wolf, Patrick Van Damme, Diego Van apex long acuminate, asymmetric, truncate or cuneate; margins entire, Meersschaut) glabrous or thinly puberulous. Inflorescence a branched, terminal panicle with male, female and hermaphrodite flowers; sepals 5, shortly deltoid, 0.5-1 cm long; petals 5, white or yellow, oblong, 3 mm long, valvate in bud, becoming reflexed; stamens 10, inserted beneath a fleshy disc; ovary superior, 1-2 mm long; styles 4, short, erect. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version Available for Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Beatriz de Aquino Ribeiro - Bióloga - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) Designation date Site Reference Number 99136-0940. Antonio Lisboa - Geógrafo - MSc. Biogeografia - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) 99137-1192. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade - ICMBio Rua Alfredo Cruz, 283, Centro, Boa Vista -RR. CEP: 69.301-140 2. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Endangered and Threatened Species

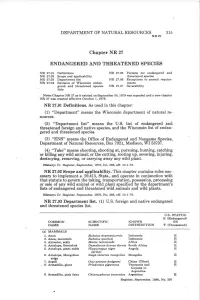

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list.