Jerks, Zombie Robots, and Other Philosophical Misadventures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

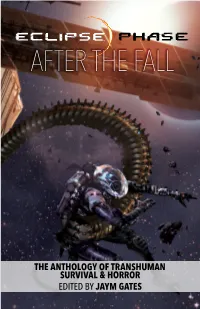

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

SESSION: Archaeology of the Future (Time Keeps on Slipping…)

SESSION: Archaeology of the future (time keeps on slipping…) North American Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG) New York University May 22-24, 2015 Organizer: Karen Holmberg (NYU, Environmental Studies) Recent interest in deep time from historical perspectives is intellectually welcome (e.g., Guldi and Armitage, 2014), though the deep past has long been the remit of archaeology so is not novel in archaeological vantages. Rather, a major shift of interest in time scale for archaeology came from historical archaeology and its relatively recent focus and adamant refusal to be the handmaiden of history. Foci on the archaeology of ‘now’ (e.g., Harrison, 2010) further refreshed and expanded the temporal playing field for archaeological thought, challenging and extending the preeminence of the deep past as the sole focus of archaeological practice. If there is a novel or intellectually challenging time frame to consider in the early 21st century, it is that of the deep future (Schellenberg, 2014). Marilyn Strathern’s (1992: 190) statement in After Nature is accurate, certainly: ‘An epoch is experienced as a now that gathers perceptions of the past into itself. An epoch will thus always will be what I have called post-eventual, that is, on the brink of collapse.’ What change of tone comes from envisioning archaeology’s role and place in a very deep future? This session invites papers that imaginatively consider the movement of time, the movement of archaeological ideas, the movement of objects, the movement of data, or any other form of movement the author would like to consider in relation to a future that only a few years ago might have been seen as a realm of science and cyborgs (per Haraway, 1991) but is increasingly fraught with dystopic environmental anxiety regarding the advent of the Anthropocene (e.g., Scranton, 2013). -

Artificial Intelligence for Interstellar Travel

Artificial Intelligence for Interstellar Travel Andreas M. Hein1 and Stephen Baxter2 1Initiative for Interstellar Studies, Bone Mill, New Street, Charfield, GL12 8ES, United Kingdom 2c/o Christopher Schelling, Selectric Artists, 9 Union Square 123, Southbury, CT 06488, USA. November 20, 2018 Abstract The large distances involved in interstellar travel require a high degree of spacecraft autonomy, realized by artificial intelligence. The breadth of tasks artificial intelligence could perform on such spacecraft involves maintenance, data collection, designing and constructing an infrastructure using in-situ resources. Despite its importance, exist- ing publications on artificial intelligence and interstellar travel are limited to cursory descriptions where little detail is given about the nature of the artificial intelligence. This article explores the role of artificial intelligence for interstellar travel by compiling use cases, exploring capabilities, and proposing typologies, system and mission archi- tectures. Estimations for the required intelligence level for specific types of interstellar probes are given, along with potential system and mission architectures, covering those proposed in the literature but also presenting novel ones. Finally, a generic design for interstellar probes with an AI payload is proposed. Given current levels of increase in computational power, a spacecraft with a similar computational power as the human brain would have a mass from dozens to hundreds of tons in a 2050 { 2060 timeframe. Given that the advent of the first interstellar missions and artificial general intelligence are estimated to be by the mid-21st century, a more in-depth exploration of the re- lationship between the two should be attempted, focusing on neglected areas such as protecting the artificial intelligence payload from radiation in interstellar space and the role of artificial intelligence in self-replication. -

Jerks, Zombie Robots, and Other Philosophical Misadventures

Jerks, Zombie Robots, and Other Philosophical Misadventures Eric Schwitzgebel Schwitzgebel July 24, 2018 Splintered Mind, 1 Dear Reader, What follows are a few dozen blog posts and popular articles, on philosophy, psychology, culture, and technology, updated and revised, selected from eleven hundred I published between 2006 and 2018. Skip the ones you hate. Eric Schwitzgebel July 24, 2018 Splintered Mind, 2 Part One: Moral Psychology 1. A Theory of Jerks 2. Forgetting as an Unwitting Confession of Your Values 3. The Happy Coincidence Defense and The-Most-I-Can-Do Sweet Spot 4. Cheeseburger Ethics (or How Often Do Ethicists Call Their Mothers?) 5. On Not Seeking Pleasure Much 6. How Much Should You Care about How You Feel in Your Dreams? 7. Imagining Yourself in Another’s Shoes vs. Extending Your Love 8. Aiming for Moral Mediocrity 9. A Theory of Hypocrisy 10. On Not Distinguishing Too Finely Among Your Motivations 11. The Mush of Normativity 12. A Moral Dunning-Kruger Effect? 13. The Moral Compass and the Liberal Ideal in Moral Education Part Two: Technology 14. Should Your Driverless Car Kill You So Others May Live? 15. Cute AI and the ASIMO Problem 16. My Daughter’s Rented Eyes 17. Someday, Your Employer Will Technologically Control Your Moods 18. Cheerfully Suicidal AI Slaves 19. We Have Greater Moral Obligations to Robots Than to (Otherwise Similar) Humans 20. Our Moral Duties to Monsters 21. Our Possible Imminent Divinity 22. Skepticism, Godzilla, and the Artificial Computerized Many-Branching You 23. How to Accidentally Become a Zombie Robot Part Three: Culture 24. -

An Overview of Mind Uploading

IOSR Journal of Engineering (IOSR JEN) www.iosrjen.org ISSN (e): 2250-3021, ISSN (p): 2278-8719 PP 18-25 An Overview of Mind Uploading Mrs. Mausami Sawarkar1, Mr. Dhiraj Rane2 Dept of CSE, Priydarshani J L CoE, Nagpur Dept. of CS, GHRIIT, Nagpur Abstract: Mind uploading is an ongoing area of active research, bringing together ideas from neuroscience, computer science, engineering, and philosophy. Realistically, mind uploading likely lies many decades in the future, but the short-term offers the possibility of advanced neural prostheses that may benefit us. Mind uploading is the conceptual futuristic technology of transferring human minds tocomputer hardware using whole-brain emulation process. In this research work, we have discuss the brief review of the technological prospectsfor mind uploading, a range of philosophical and ethical aspects of the technology. We have also summarizes various issues for mind uploading. There are many technologies are working on these issues will be summarize. These include questions about whether uploads will have consciousness and whether uploading willpreserve personal identity, as well as what impact on society a working uploading technology is likelyto have and whether these impacts are desirable. The issue of whether we ought to move forwardstowards uploading technology remains as unclear as ever. Keywords: Mind Uploading, Whole brain simulation, I. Introduction Mind uploading is an ongoing area of active research, bringing together ideas from neuroscience, computer science, engineering, and philosophy. Realistically, mind uploading likely lies many decades in the future, but the short-term offers the possibility of advanced neural prostheses that may benefit us. Mind uploading is a popular term for a process by which the mind, a collection of memories, personality, and attributes of a specific individual, is transferred from its original biological brain to an artificial computational substrate. -

Fermi Paradox from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Fermi paradox From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the absence of evidence for extraterrestrial intelligence. For the type of estimation problem, see Fermi problem. For the music album, see Fermi Paradox (album). For the short story, see The Fermi Paradox Is Our Business Model. A graphical representation of the Arecibo message – Humanity's first attempt to use radio waves to actively communicate its existence to alien civilizations The Fermi paradox (or Fermi's paradox) is the apparent contradiction between high estimates of the probability of the existence of extraterrestrial civilization and humanity's lack of contact with, or evidence for, such civilizations.[1] The basic points of the argument, made by physicists Enrico Fermi and Michael H. Hart, are: • The Sun is a young star. There are billions of stars in the galaxy that are billions of years older; • Some of these stars likely have Earth-like planets[2] which, if the Earth is typical, may develop intelligent life; • Presumably some of these civilizations will develop interstellar travel, as Earth seems likely to do; • At any practical pace of interstellar travel, the galaxy can be completely colonized in just a few tens of millions of years. According to this line of thinking, the Earth should have already been colonized, or at least visited. But no convincing evidence of this exists. Furthermore, no confirmed signs of intelligence elsewhere have been spotted, either in our galaxy or the more than 80 billion other galaxies of the -

Full Page Photo

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 6 No. 1; January 2017 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Posthuman Reconstruction of the World as a Simulation in Charles Stross’ Accelerando Indrajit Patra (Corresponding author) National Institute of Technology, Durgapur), India E-mail: [email protected] Shri Krishan Rai Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology), India Received: 01-07-2016 Accepted: 07-09-2016 Advance Access Published: November 2016 Published: 02-01-2017 doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.1p.136 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.1p.136 Abstract In this paper my aim is to analyze the theme of simulation in Charles Stross’ hard science fiction novel titled ‘Accelerando’ (2005). The discussion shall start by pointing out the enormous significance of the ideas of simulation both in the world of pure science as well as in the fields of philosophy, arts and literature. We shall show by adopting an informational approach and by using the theoretical framework of Baudrillard’s ‘Simulacra and Simulation’ that science fiction novels like Charles Stross’ ‘Accelerando’ treat simulation not just as an abstract mathematical entity existing independently of human beings; rather they treat simulation as an indispensable step for mankind in their journey of ascension to the Posthuman plane of existence. This paper will also try to prove that Stross’ ‘Accelerando’ not only relies upon the description of the effects of use of many incomprehensibly powerful simulation technologies in various forms to produce the effect of estrangement upon the readers but it also implies that the very fabric of reality which deem to be real is composed of binary oppositions between different strands of contradistinctive signs and symbols which in a posthuman world will crumble together to give way to a Posthuman world replete with endless possibilities. -

Cultural History of the Science and Technology of Human Enhancement

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Engineering humans : cultural history of the science and technology of human enhancement https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40210/ Version: Full Version Citation: Haug, Knut Hallvard Sverre (2016) Engineering humans : cul- tural history of the science and technology of human enhancement. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 Engineering Humans a cultural history of the science and technology of human enhancement Knut Hallvard Sverre Haug Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Humanities School of Arts Birkbeck, University of London 2015 2 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Hallvard Haug 3 Abstract This thesis investigates the technological imaginary of human enhancement: how it has been conceived historically and the scientific understanding that has shaped it. Human enhancement technologies have been prominent in popular culture narratives for a long time, but in the past twenty years they have moved out of science fiction to being an issue for serious discussion, in academic disciplines, political debate and the mass media.. Even so, the bioethical debate on enhancement, whether it is pharmacological means of improving cognition and morality or genetic engineering to create smarter people or other possibilities, is consistently centred on technologies that do not yet exist. The investigation is divided into three main areas: a chapter on eugenics, two chapters on cybernetics and the cyborg, and two chapters on transhumanism. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara a Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz a Diss

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Kathleen Anne Swift Committee in charge: Professor Richard Duran, Chair Professor Diana Arya Professor William Robinson September 2017 The dissertation of Kathleen Anne Swift is approved. ................................................................................................................................ Diana Arya ................................................................................................................................ William Robinson ................................................................................................................................ Richard Duran, Committee Chair June 2017 A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Copyright © 2017 by Kathleen Anne Swift iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their advice and patience as I worked on gathering and analyzing the copious amounts of research necessary to write this dissertation. Ongoing conversations about hacktivism, Anonymous, Swartz, Snowden, and the rise of the surveillance state have been interesting to say the least. I appreciate all the counsel and guidance I have received over the years. In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. -

Science Fiction 45 Min Video Outline

Science Fiction: The Mythology of the Future Tom Lombardo, Ph.D. Center for Future Consciousness www.centerforfutureconsciousness.com Part I What is Science Fiction? Why is it so Popular? On the Magazine Cover is Braxa, a Martian Holding a Rose - as a Symbol of Bittersweet Connection between Herself & Human Character who has Impregnated Her, Saving the Martian Race from Extinction - “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” (1963) by Roger Zelazny - Science Fiction Hall of Fame - Contradicts Techno-Stereotype of Science Fiction - Humanistic Tale Takes Place on Mars - Story of Religion & Fate & Fatalism About the Future - Of Love & Seduction - Of Mysticism vs. Rationalism - Central Character is Poet & Linguist Not a Scientist or Technologist - Zelazny Incorporated Themes of Mythology into much of his Science Fiction Science fiction is clearly the most visible & influential contemporary form of futurist thinking in the modern world. Science fiction is so popular because science fiction speaks to the whole person— intellect, imagination, & emotion—and stimulates holistic future consciousness. Definition of Science Fiction: Although not all science fiction deals with the future, its primary focus has been on the possibilities of the future. In this regard, science fiction can be defined as a literary and narrative approach to the future, involving plots, story lines and action sequences, specific settings, dramatic resolutions, and varied and unique characters, human and otherwise. It is imaginative, concrete, and often highly detailed scenario-building about the -

Top 10 Reasons We Should Fear the Singularity 19/08/2019, 3�25 PM

Top 10 Reasons We Should Fear The Singularity 19/08/2019, 325 PM Top 10 Reasons We Should Fear The Singularity Socrates Why do we fear the technological singularity? Well, let me give you what I believe are the top 10 most popular reasons: 1. Extinction Extinction is by far the most feared as well as the most commonly predicted consequence of the singularity. The global apocalypse for the human race comes in many flavors but some of the most popular ones are: the supersmart terminator AI’s – a robopocalypse; nanotechnology gone rogue – the so called grey goo scenario, home-made Smart Weapons of Mass Destruction – used by terrorists and nihilists; genetic modifications or mutations – turning us into living- dead zombies; science experiments gone wrong – the Large Hadron Collider creating a black hole that engulfs the planet… In short, the fear is that, as Bill Joy notoriously put it: The Future Doesn’t Need Us. 2. Slavery Perhaps the second most common reason for fearing the singularity is the potential slavery or subjugation of the entire human race. The argument is pretty straight forward: Once we have super smart AIs we stop being the smartest entities on this planet. In other words, we have created Gods while remaining mere humans. So, if for whatever reason the machines decide not to exterminate us, then, chances are that, since they will be vastly superior to us, they will enslave us. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways: either explicitly – with us being aware of our bondage, or implicitly – without us realizing it (the Matrix/simulation scenarios). -

Artificial Intelligence Probes for Interstellar Exploration and Colonization

Artificial Intelligence Probes for Interstellar Exploration and Colonization Andreas M. Hein Initiative for Interstellar Studies, 27-29 South Lambeth Road, London SW8 1SZ, United Kingdom Abstract A recurring topic in interstellar exploration and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) is the role of artificial intelligence. More precisely, these are programs or devices that are capable of performing cognitive tasks that have been previously associated with humans such as image recognition, reasoning, decision-making etc. Such systems are likely to play an important role in future deep space missions, notably interstellar exploration, where the spacecraft needs to act autonomously. This article explores the drivers for an interstellar mission with a computation-heavy payload and provides an outline of a spacecraft and mission architecture that supports such a payload. Based on existing technologies and extrapolations of current trends, it is shown that AI spacecraft development and operation will be constrained and driven by three aspects: power requirements for the payload, power generation capabilities, and heat rejection capabilities. A likely mission architecture for such a probe is to get into an orbit close to the star in order to generate maximum power for computational activities, and then to prepare for further exploration activities. Given current levels of increase in computational power, such a payload with a similar computational power as the human brain would have a mass of hundreds to dozens of tons in a 2050 – 2060 timeframe. Key words: Interstellar travel, artificial intelligence, computing, SETI, matrioshka brain 1. Introduction A recurring topic in interstellar exploration and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) is the role of artificial intelligence (Armstrong and Sandberg, 2013; Dick, 2003; Tipler and Barrow, 1986; Tipler, 1994).