UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara a Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz a Diss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6w76f8x7 Author Swift, Kathy Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Kathleen Anne Swift Committee in charge: Professor Richard Duran, Chair Professor Diana Arya Professor William Robinson September 2017 The dissertation of Kathleen Anne Swift is approved. ................................................................................................................................ Diana Arya ................................................................................................................................ William Robinson ................................................................................................................................ Richard Duran, Committee Chair June 2017 A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Copyright © 2017 by Kathleen Anne Swift iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their advice and patience as I worked on gathering and analyzing the copious amounts of research necessary to -

Allen W. Dulles and the CIA

THE GILDED AGE Allen W. Dulles and the CIA Allen W. Dulles spent his tenure as the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) entrenched in secret power struggles that would ensure his ultimate power over the foreign and domestic aff airs for the United States. Th roughout his childhood, Dulles learned to use political power in order to get ahead, and to use secrecy to make unilateral deci- sions. Aft er analyzing examples of his treatment of various foreign aff airs disasters, as well as his manipulation of American media and politicians, Dulles is exposed as a man whose legacy lives in the CIA, as a legendary fi gure who is in fact much more of a craft ed legend than a man of truth. By Sada O. Stewart ‘16 Princeton University of the CIA’s own making, the product of the publicity and the political propaganda Allen Dulles manufactured in the 1950s.”4 How, though, did Dulles craft a fl awless, genius im- age for the CIA? What methods did Dulles use to manipulate the press, the public, and even the other branches of govern- ment to bring forth an agency with “a great reputation and a terrible record?”5 Dulles made the CIA seem like an elite agency full of top agents resulting in high risk, high reward missions—how is this reconciled with the reality of the CIA under Dulles’ reign? INTELLIGENCE IN YOUTH To begin, it is vital to identify the signifi cance of developing and running an intelligence agency in an open democratic system.6 Sun Tzu, author of Th e Art of War, insists the best A Bas-relief of Allen Dulles at the Original Headquarters of (only) way to fi ght a war is to know the enemy. -

The Palgrave Handbook of Digital Russia Studies

The Palgrave Handbook of Digital Russia Studies Edited by Daria Gritsenko Mariëlle Wijermars · Mikhail Kopotev The Palgrave Handbook of Digital Russia Studies Daria Gritsenko Mariëlle Wijermars • Mikhail Kopotev Editors The Palgrave Handbook of Digital Russia Studies Editors Daria Gritsenko Mariëlle Wijermars University of Helsinki Maastricht University Helsinki, Finland Maastricht, The Netherlands Mikhail Kopotev Higher School of Economics (HSE University) Saint Petersburg, Russia ISBN 978-3-030-42854-9 ISBN 978-3-030-42855-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42855-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2021. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

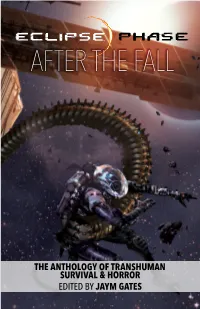

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Dark and Deep Webs-Liberty Or Abuse

International Journal of Cyber Warfare and Terrorism Volume 9 • Issue 2 • April-June 2019 Dark and Deep Webs-Liberty or Abuse Lev Topor, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1836-5150 ABSTRACT While the Dark Web is the safest internet platform, it is also the most dangerous platform at the same time. While users can stay secure and almost totally anonymously, they can also be exploited by other users, hackers, cyber-criminals, and even foreign governments. The purpose of this article is to explore and discuss the tremendous benefits of anonymous networks while comparing them to the hazards and risks that are also found on those platforms. In order to open this dark portal and contribute to the discussion of cyber and politics, a comparative analysis of the dark and deep web to the commonly familiar surface web (World Wide Web) is made, aiming to find and describe both the advantages and disadvantages of the platforms. KeyWoRD Cyber, DarkNet, Information, New Politics, Web, World Wide Web INTRoDUCTIoN In June 2018, the United States Department of Justice uncovered its nationwide undercover operation in which it targeted dark web vendors. This operation resulted in 35 arrests and seizure of weapons, drugs, illegal erotica material and much more. In total, the U.S. Department of Justice seized more than 23.6$ Million.1 In that same year, as in past years, the largest dark web platform, TOR (The Onion Router),2 was sponsored almost exclusively by the U.S. government and other Western allies.3 Thus, an important and even philosophical question is derived from this situation- Who is responsible for the illegal goods and cyber-crimes? Was it the criminal[s] that committed them or was it the facilitator and developer, the U.S. -

From Clicktivism to Hacktivism: Understanding Digital Activism

Information & Organization, forthcoming 2019 1 From Clicktivism to Hacktivism: Understanding Digital Activism Jordana J. George Dorothy E. Leidner Mays Business School, Texas A&M University Baylor University ABSTRACT Digital activism provides new opportunities for social movement participants and social movement organizations (SMOs). Recent IS research has begun to touch on digital activism, defining it, exploring it, and building new theory to help understand it. This paper seeks to unpack digital activism through an exploratory literature review that provides descriptions, definitions, and categorizations. We provide a framework for digital activism by extending Milbrath’s (1965) hierarchy of political participation that divides activism into spectator, transitional, and gladiatorial activities. Using this framework, we identify ten activities of digital activism that are represented in the literature. These include digital spectator activities: clicktivism, metavoicing, assertion; digital transitional activities: e-funding, political consumerism, digital petitions, and botivism; and digital gladiatorial activities: data activism, exposure, and hacktivism. Last, we analyze the activities in terms of participants, SMOs, individuals who are targeted by the activity, and organizations that are targeted by the activity. We highlight four major implications and offer four meta-conjectures on the mechanisms of digital activism and their resulting impacts, and reveal a new construct where participants digitally organize yet lack an identifying cause, which we label connective emotion. Key Words Digital activism, social activism, political participation, social movements, connective emotion, literature review 1.0 Introduction Not long ago, activism to promote social movements was relegated to demonstrations and marches, chaining oneself to a fence, or writing to a government representative. Recruiting, organizing, and retaining participants was difficult enough to ensure that often only largest, best supported movements thrived and creating an impact often took years. -

Report to the President: MIT and the Prosecution of Aaron Swartz

Report to the President MIT and the Prosecution of Aaron Swartz Review Panel Harold Abelson Peter A. Diamond Andrew Grosso Douglas W. Pfeiffer (support) July 26, 2013 © Copyright 2013, Massachusetts Institute of Technology This worK is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. PRESIDENT REIF’S CHARGE TO HAL ABELSON | iii L. Rafael Reif, President 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Building 3-208 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 U.S.A. Phone 1-617-253-0148 !"#$"%&'(()'(*+,' ' -."%'/%01.220%'34.520#6' ' 78#9.'1"55'(*+*)':;<'="2'4..#'8#>05>.?'8#'.>.#@2'"%828#A'1%0B'"9@80#2'@"C.#'4&'3"%0#'7D"%@E'@0' "99.22'!7<FG'@=%0$A='@=.':;<'90BH$@.%'#.@D0%CI';'=">.'"2C.?'&0$)'"#?'&0$'=">.'A%"980$25&' "A%..?)'@0'%.>8.D':;<J2'8#>05>.B.#@I' ' <=.'H$%H02.'01'@=82'%.>8.D'82'@0'?.29%84.':;<J2'"9@80#2'"#?'@0'5."%#'1%0B'@=.BI'K0$%'%.>8.D' 2=0$5?'L+M'?.29%84.':;<J2'"9@80#2'"#?'?.98280#2'?$%8#A'@=.'H.%80?'4.A8##8#A'D=.#':;<'18%2@' 4.9"B.'"D"%.'01'$#$2$"5'!7<FGN%.5"@.?'"9@8>8@&'0#'8@2'#.@D0%C'4&'"'@=.#N$#8?.#@818.?'H.%20#)' $#@85'@=.'?."@='01'3"%0#'7D"%@E'0#'!"#$"%&'++)'(*+,)'L(M'%.>8.D'@=.'90#@.O@'01'@=.2.'?.98280#2'"#?' @=.'0H@80#2'@="@':;<'90#28?.%.?)'"#?'L,M'8?.#@81&'@=.'822$.2'@="@'D"%%"#@'1$%@=.%'"#"5&282'8#'0%?.%' @0'5."%#'1%0B'@=.2.'.>.#@2I' ' ;'@%$2@'@="@'@=.':;<'90BB$#8@&)'8#95$?8#A'@=02.'8#>05>.?'8#'@=.2.'.>.#@2)'"5D"&2'"9@2'D8@='=8A=' H%01.2280#"5'8#@.A%8@&'"#?'"'2@%0#A'2.#2.'01'%.2H0#284858@&'@0':;<I'P0D.>.%)':;<'@%8.2'90#@8#$0$25&' @0'8BH%0>.'"#?'@0'B..@'8@2'=8A=.2@'"2H8%"@80#2I';@'82'8#'@="@'2H8%8@'@="@';'"2C'&0$'@0'=.5H':;<'5."%#' 1%0B'@=.2.'.>.#@2I' -

Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police Its Police

DePaul Journal for Social Justice Volume 10 Issue 1 Winter 2017 Article 2 February 2017 Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police Elizabeth J. Andonova Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Social Welfare Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth J. Andonova, Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police, 10 DePaul J. for Soc. Just. (2017) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andonova: Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police I Author: Elizabeth J. Andonova Source: The National Lawyers Guild Source Citation: 73 LAW. GUILD REV. 2 (2016) Title: Cycle of Misconduct: How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police the Police Republication Notice This article is being republished with the express consent of The National Lawyers Guild. This article was originally published in the National Lawyers Guild Summer 2016 Review, Volume 73, Number 2. That document can be found at: https://www.nlg.org/nlg-review/wp- content/uploads/sites/2/2016/11/NLGRev-73-2-final-digital.pdf. The DePaul Journal for Social Justice would like to thank the NLG for granting us the permission to republish this article. -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

SESSION: Archaeology of the Future (Time Keeps on Slipping…)

SESSION: Archaeology of the future (time keeps on slipping…) North American Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG) New York University May 22-24, 2015 Organizer: Karen Holmberg (NYU, Environmental Studies) Recent interest in deep time from historical perspectives is intellectually welcome (e.g., Guldi and Armitage, 2014), though the deep past has long been the remit of archaeology so is not novel in archaeological vantages. Rather, a major shift of interest in time scale for archaeology came from historical archaeology and its relatively recent focus and adamant refusal to be the handmaiden of history. Foci on the archaeology of ‘now’ (e.g., Harrison, 2010) further refreshed and expanded the temporal playing field for archaeological thought, challenging and extending the preeminence of the deep past as the sole focus of archaeological practice. If there is a novel or intellectually challenging time frame to consider in the early 21st century, it is that of the deep future (Schellenberg, 2014). Marilyn Strathern’s (1992: 190) statement in After Nature is accurate, certainly: ‘An epoch is experienced as a now that gathers perceptions of the past into itself. An epoch will thus always will be what I have called post-eventual, that is, on the brink of collapse.’ What change of tone comes from envisioning archaeology’s role and place in a very deep future? This session invites papers that imaginatively consider the movement of time, the movement of archaeological ideas, the movement of objects, the movement of data, or any other form of movement the author would like to consider in relation to a future that only a few years ago might have been seen as a realm of science and cyborgs (per Haraway, 1991) but is increasingly fraught with dystopic environmental anxiety regarding the advent of the Anthropocene (e.g., Scranton, 2013). -

Hard-Coded Censorship in Open Source Mastodon Clients — How Free Is Open Source?

Proceedings of the Conference on Technology Ethics 2020 - Tethics 2020 Hard-coded censorship in Open Source Mastodon clients — How Free is Open Source? Long paper Juhani Naskali 0000-0002-7559-2595 Information Systems Science, Turku School of Economics, University of Turku Turku, Finland juhani.naskali@utu.fi Abstract. This article analyses hard-coded domain blocking in open source soft- ware, using the GPL3-licensed Mastodon client Tusky as a case example. First, the question of whether such action is censorship is analysed. Second, the licensing compliance of such action is examined using the applicable open-source software and distribution licenses. Domain blocking is found to be censorship in the literal definition of the word, as well as possibly against some the used Google distribu- tion licenses — though some ambiguity remains, which calls for clarifications in the agreement terms. GPL allows for functionalities that limit the use of the software, as long as end-users are free to edit the source code and use a version of the appli- cation without such limitations. Such software is still open source, but no longer free (as in freedom). A multi-disciplinary ethical examination of domain blocking will be needed to ascertain whether such censorship is ethical, as all censorship is not necessarily wrong. Keywords: open source, FOSS, censorship, domain blocking, licensing terms 1 Introduction New technologies constantly create new challenges. Old laws and policies cannot al- ways predict future possibilities, and sometimes need to be re-examined. Open source software is a licensing method to freely distribute software code, but also an ideology of openness and inclusiveness, especially when it comes to FOSS (Free and Open-source software).