UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dark and Deep Webs-Liberty Or Abuse

International Journal of Cyber Warfare and Terrorism Volume 9 • Issue 2 • April-June 2019 Dark and Deep Webs-Liberty or Abuse Lev Topor, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1836-5150 ABSTRACT While the Dark Web is the safest internet platform, it is also the most dangerous platform at the same time. While users can stay secure and almost totally anonymously, they can also be exploited by other users, hackers, cyber-criminals, and even foreign governments. The purpose of this article is to explore and discuss the tremendous benefits of anonymous networks while comparing them to the hazards and risks that are also found on those platforms. In order to open this dark portal and contribute to the discussion of cyber and politics, a comparative analysis of the dark and deep web to the commonly familiar surface web (World Wide Web) is made, aiming to find and describe both the advantages and disadvantages of the platforms. KeyWoRD Cyber, DarkNet, Information, New Politics, Web, World Wide Web INTRoDUCTIoN In June 2018, the United States Department of Justice uncovered its nationwide undercover operation in which it targeted dark web vendors. This operation resulted in 35 arrests and seizure of weapons, drugs, illegal erotica material and much more. In total, the U.S. Department of Justice seized more than 23.6$ Million.1 In that same year, as in past years, the largest dark web platform, TOR (The Onion Router),2 was sponsored almost exclusively by the U.S. government and other Western allies.3 Thus, an important and even philosophical question is derived from this situation- Who is responsible for the illegal goods and cyber-crimes? Was it the criminal[s] that committed them or was it the facilitator and developer, the U.S. -

Guide De Protection Numérique Des Sources Journalistiques

Guide de Protection numérique des Sources journalistiques Mise en œuvre simplifiée Par Hector Sudan Version du document : 23.04.2021 Mises à jour disponibles gratuitement sur https://sourcesguard.ch/publications Guide de Protection numérique des Sources journalistiques Les journalistes ne sont pas suffisamment sensibilisés aux risques numé- riques et ne disposent pas assez d'outils pour s'en protéger. C'est la consta- tation finale d'une première recherche sociologique dans le domaine jour- nalistique en Suisse romande. Ce GPS (Guide de Protection numérique des Sources) est le premier résultat des recommandations de cette étude. Un GPS qui ne parle pas, mais qui va droit au but en proposant des solutions concrètes pour la sécurité numérique des journalistes et de leurs sources. Il vous est proposé une approche andragogique et tactique, de manière résumée, afin que vous puissiez mettre en œuvre rapidement des mesures visant à améliorer votre sécurité numérique, tout en vous permettant d'être efficient. Même sans être journaliste d'investigation, vos informations et votre protection sont importantes. Vous n'êtes peut-être pas directement la cible, mais pouvez être le vecteur d'une attaque visant une personne dont vous avez les informations de contact. Hector Sudan est informaticien au bénéfice d'un Brevet fédéral en technique des sys- tèmes et d'un MAS en lutte contre la crimina- lité économique. Avec son travail de master l'Artiste responsable et ce GPS, il se posi- tionne comme chercheur, formateur et consul- tant actif dans le domaine de la sécurité numé- rique pour les médias et journalistes. +41 76 556 43 19 keybase.io/hectorsudan [email protected] SourcesGuard Avant propos Ce GPS (Guide de Protection numérique des Sources journalistes) est à l’image de son acronyme : concis, clair, allant droit au but, tout en offrant la possibilité de passer par des chemins techniquement complexes. -

Mitigating the Risks of Whistleblowing an Approach Using Distributed System Technologies

Mitigating the Risks of Whistleblowing An Approach Using Distributed System Technologies Ali Habbabeh1, Petra Maria Asprion1, and Bettina Schneider1 1 University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland, Basel, Switzerland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract. Whistleblowing is an effective tool to fight corruption and expose wrongdoing in governments and corporations. Insiders who are willing to report misconduct, called whistleblowers, often seek to reach a recipient who can dis- seminate the relevant information to the public. However, whistleblowers often face many challenges to protect themselves from retaliation when using the ex- isting (centralized) whistleblowing platforms. This study discusses several asso- ciated risks of whistleblowing when communicating with third parties using web- forms of newspapers, trusted organizations like WikiLeaks, or whistleblowing software like GlobaLeaks or SecureDrop. Then, this study proposes an outlook to a solution using decentralized systems to mitigate these risks using Block- chain, Smart Contracts, Distributed File Synchronization and Sharing (DFSS), and Distributed Domain Name Systems (DDNS). Keywords: Whistleblowing, Blockchain, Smart Contracts 1 Introduction By all indications, the topic of whistleblowing has been gaining extensive media atten- tion since the financial crisis in 2008, which ignited a crackdown on the corruption of institutions [1]. However, some whistleblowers have also become discouraged by the negative association with the term [2], although numerous studies show that whistle- blowers have often revealed misconduct of public interest [3]. Therefore, researchers like [3] argue that we - the community of citizens - must protect whistleblowers. Addi- tionally, some researchers, such as [1], claim that, although not perfect, we should re- ward whistleblowers financially to incentivize them to speak out to fight corruption [1]. -

The Dark Net Free

FREE THE DARK NET PDF Jamie Bartlett | 320 pages | 12 Mar 2015 | Cornerstone | 9780099592020 | English | London, United Kingdom What Is the Dark Net? A dark net or darknet is an overlay network within the Internet that can only be accessed with specific software, configurations, or The Dark Net, [1] and often uses a unique customised communication protocol. Two typical darknet types are social networks [2] usually used for file hosting with a peer-to-peer connection[3] and anonymity proxy networks such as Tor via an anonymized series of connections. The term The Dark Net was popularised by major news outlets to associate with Tor Onion serviceswhen the infamous drug bazaar Silk Road used it, [4] despite the terminology being unofficial. Technology such as TorI2Pand Freenet was intended to defend digital rights by providing security, anonymity, or censorship resistance and is used for both illegal and legitimate reasons. Anonymous communication between whistle- blowersactivists, journalists and news organisations is also facilitated The Dark Net darknets through use of applications such as SecureDrop. The term originally The Dark Net computers on ARPANET that were hidden, programmed to receive messages but not respond to or acknowledge anything, thus remaining invisible, in the dark. Since ARPANETthe usage of dark net has expanded to include friend-to-friend networks usually used for file sharing with a peer-to-peer connection and privacy networks such as Tor. The term "darknet" is often used interchangeably with The Dark Net " dark web " due to the quantity of hidden services on Tor 's darknet. The term is often inaccurately used interchangeably with the deep web due to Tor's history as a platform that could not be search-indexed. -

The Tor Dark Net

PAPER SERIES: NO. 20 — SEPTEMBER 2015 The Tor Dark Net Gareth Owen and Nick Savage THE TOR DARK NET Gareth Owen and Nick Savage Copyright © 2015 by Gareth Owen and Nick Savage Published by the Centre for International Governance Innovation and the Royal Institute of International Affairs. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for International Governance Innovation or its Board of Directors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — Non-commercial — No Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/3.0/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice. 67 Erb Street West 10 St James’s Square Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2 London, England SW1Y 4LE Canada United Kingdom tel +1 519 885 2444 fax +1 519 885 5450 tel +44 (0)20 7957 5700 fax +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.cigionline.org www.chathamhouse.org TABLE OF CONTENTS vi About the Global Commission on Internet Governance vi About the Authors 1 Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Hidden Services 2 Related Work 3 Study of HSes 4 Content and Popularity Analysis 7 Deanonymization of Tor Users and HSes 8 Blocking of Tor 8 HS Blocking 9 Conclusion 9 Works Cited 12 About CIGI 12 About Chatham House 12 CIGI Masthead GLOBAL COMMISSION ON INTERNET GOVERNANCE PAPER SERIES: NO. 20 — SEPTEMBER 2015 ABOUT THE GLOBAL ABOUT THE AUTHORS COMMISSION ON INTERNET Gareth Owen is a senior lecturer in the School of GOVERNANCE Computing at the University of Portsmouth. -

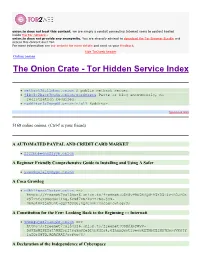

The Onion Crate - Tor Hidden Service Index Protected Onions Add New

onion.to does not host this content; we are simply a conduit connecting Internet users to content hosted inside the Tor network.. onion.to does not provide any anonymity. You are strongly advised to download the Tor Browser Bundle and access this content over Tor. For more information see our website for more details and send us your feedback. hide Tor2web header Online onions The Onion Crate - Tor Hidden Service Index Protected onions Add new nethack3dzllmbmo.onion A public nethack server. j4ko5c2kacr3pu6x.onion/wordpress Paste or blog anonymously, no registration required. redditor3a2spgd6.onion/r/all Redditor. Sponsored links 5168 online onions. (Ctrl-f is your friend) A AUTOMATED PAYPAL AND CREDIT CARD MARKET 2222bbbeonn2zyyb.onion A Beginner Friendly Comprehensive Guide to Installing and Using A Safer yuxv6qujajqvmypv.onion A Coca Growlog rdkhliwzee2hetev.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:USK@yP9U5NBQd~h5X55i4vjB0JFOX P97TAtJTOSgquP11Ag,6cN87XSAkuYzFSq-jyN- 3bmJlMPjje5uAt~gQz7SOsU,AQACAAE/cocagrowlog/3/ A Constitution for the Few: Looking Back to the Beginning ::: Internati 5hmkgujuz24lnq2z.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:USK@kpFWyV- 5d9ZmWZPEIatjWHEsrftyq5m0fe5IybK3fg4,6IhxxQwot1yeowkHTNbGZiNz7HpsqVKOjY 1aZQrH8TQ,AQACAAE/acftw/0/ A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace ufbvplpvnr3tzakk.onion ==> https://freenet7cul5qsz6.onion.to/freenet:CHK@9NuTb9oavt6KdyrF7~lG1J3CS g8KVez0hggrfmPA0Cw,WJ~w18hKJlkdsgM~Q2LW5wDX8LgKo3U8iqnSnCAzGG0,AAIC-- 8/Declaration-Final%5b1%5d.html A Dumps Market -

The Ultimate Guide TOR & the Deep Dark Web by Join My List Here

The Ultimate Guide TOR & the Deep Dark Web (For Beginners) by THOMAS CRENSHAW Join my list here Legal Stuff: While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information presented here is correct, the contents herein are a reflection of the views of the author and are meant for educational and informational purposes only. All links are for information purposes only and are not warranted for content, accuracy or any other implied or explicit purpose. No guarantees whatsoever, be it fiduciary or in terms of any guaranteed results are made, and as always competent legal, accounting, tax and other professional consultation should be sought where needed. The author shall in no event be held liable for any loss or other damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential or other damages. Photos are from royalty free websites and can be used in any manner. Warning: This is copyrighted material. It is illegal to copy, print or use any part of this e-book for any reason whatsoever. Copyright 2019 / Empower777.com/ All rights reserved. Note: My team and I have purposely repeated certain paragraphs through out the book in order to help you to retain it – we always repeat certain things of interest that should be ingrained in your mind as the reader. Repeating certain things is done on purpose – it is not an accident. What’s Inside: • How To Safely Access The Deep Dark Webs • Here Are A Few Safety Issues To Consider • Dos And Don’ts On The Dark Web • How The Dark Web Can Be Dangerous • Are You Wanting To FIND Deep Websites – This Is How You Do It • Deep Web Vs. -

Design of the Next-Generation Securedrop Workstation Freedom of the Press Foundation

1 Design of the Next-Generation SecureDrop Workstation Freedom of the Press Foundation I. INTRODUCTION Whistleblowers expose wrongdoing, illegality, abuse, misconduct, waste, and/or threats to public health or safety. Whistleblowing has been critical for some of the most important stories in the history of investigative journalism, e.g. the Pentagon Papers, the Panama Papers, and the Snowden disclosures. From the Government Accountability Project’s Whistleblower Guide (1): The power of whistleblowers to hold institutions and leaders accountable very often depends on the critical work of journalists, who verify whistleblowers’ disclosures and then bring them to the public. The partnership between whistleblowers and journalists is essential to a functioning democracy. In the United States, shield laws and reporter’s privilege exists to protect the right of a journalist to not reveal the identity of a source. However, under both the Obama and Trump administrations, governments have attempted to identify journalistic sources via court orders to third parties holding journalist’s records. Under the Obama administration, the Associated Press had its telephone records acquired in order to identify a source (2). Under the Trump Administration, New York Times journalist Ali Watkins had her phone and email records acquired by court order (3). If source—journalist communications are mediated by third parties that can be subject to subpoena, source identities can be revealed without a journalist being aware due to a gag that is often associated with such court orders. Sources can face a range of reprisals. These could be personal reprisals such as reputational or relationship damage, or for employees that reveal wrongdoing, loss of employment and career opportunities. -

Anonymous Javascript Cryptography and Cover Traffic in Whistleblowing Applications

DEGREE PROJECT IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2016 Anonymous Javascript Cryptography and Cover Traffic in Whistleblowing Applications JOAKIM UDDHOLM KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND COMMUNICATION Anonymous Javascript Cryptography and Cover Traffic in Whistleblowing Applications JOAKIM HJALMARSSON UDDHOLM Master’s Thesis at NADA Supervisor: Sonja Buchegger, Daniel Bosk Examiner: Johan Håstad Abstract In recent years, whistleblowing has lead to big headlines around the world. This thesis looks at whistleblower systems, which are systems specifically created for whistleblowers to submit tips anonymously. The problem is how to engineer such a system as to maximize the anonymity for the whistleblower whilst at the same time remain usable. The thesis evaluates existing implementations for the whistle- blowing problem. Eleven Swedish newspapers are evaluated for potential threats against their whistleblowing service. I suggest a new system that tries to improve on existing sys- tems. New features includes the introduction of JavaScript cryp- tography to lessen the reliance of trust for a hosted server. Use of anonymous encryption and cover traffic to partially anonymize the recipient, size and timing metadata on submissions sent by the whistleblowers. I explore the implementations of these fea- tures and the viability to address threats against JavaScript in- tegrity by use of cover traffic. The results show that JavaScript encrypted submissions are viable. The tamper detection system can provide some integrity for the JavaScript client. Cover traffic for the initial submissions to the journalists was also shown to be feasible. However, cover traffic for replies sent back-and-forth between whistleblower and journalist consumed too much data transfer and was too slow to be useful. -

Detection and Analysis of Tor Onion Services

Detection and Analysis of Tor Onion Services Martin Steinebach1;∗, Marcel Schäfer2, Alexander Karakuz and Katharina Brandl1 1Fraunhofer SIT, Germany 2Fraunhofer USA CESE E-mail: [email protected] ∗Corresponding Author Received 28 November 2019; Accepted 28 November 2019; Publication 23 January 2020 Abstract Tor onion services can be accessed and hosted anonymously on the Tor network. We analyze the protocols, software types, popularity and uptime of these services by collecting a large amount of .onion addresses. Websites are crawled and clustered based on their respective language. In order to also determine the amount of unique websites a de-duplication approach is implemented. To achieve this, we introduce a modular system for the real-time detection and analysis of onion services. Address resolution of onion services is realized via descriptors that are published to and requested from servers on the Tor network that volunteer for this task. We place a set of 20 volunteer servers on the Tor network in order to collect .onion addresses. The analysis of the collected data and its comparison to previous research provides new insights into the current state of Tor onion services and their development. The service scans show a vast variety of protocols with a significant increase in the popularity of anonymous mail servers and Bitcoin clients since 2013. The popularity analysis shows that the majority of Tor client requests is performed only for a small subset of addresses. The overall data reveals further that a large amount of permanent services provide no actual content for Tor users. A significant part consists instead of bots, services offered via multiple domains, or duplicated websites for phishing Journal of Cyber Security and Mobility, Vol. -

Cyber Security in a Volatile World

Research Volume Five Global Commission on Internet Governance Cyber Security in a Volatile World Research Volume Five Global Commission on Internet Governance Cyber Security in a Volatile World Published by the Centre for International Governance Innovation and the Royal Institute of International Affairs The copyright in respect of each chapter is noted at the beginning of each chapter. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for International Governance Innovation or its Board of Directors. This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of IDRC or its Board of Governors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — Non-commercial — No Derivatives License. To view this licence, visit (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice. Centre for International Governance Innovation, CIGI and the CIGI globe are registered trademarks. 67 Erb Street West 10 St James’s Square Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2 London, England SW1Y 4LE Canada United Kingdom tel +1 519 885 2444 fax +1 519 885 5450 tel +44 (0)20 7957 5700 fax +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.cigionline.org www.chathamhouse.org TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Global Commission on Internet Governance . .iv . Preface . v Carl Bildt Introduction: Security as a Precursor to Internet Freedom and Commerce . .1 . Laura DeNardis Chapter One: Global Cyberspace Is Safer than You Think: Real Trends in Cybercrime . -

Overview of Whistleblowing Software

U4 Helpdesk Answer Overview of whistleblowing software Author: Matthew Jenkins, Transparency International, [email protected] Reviewers: Marie Terracol, Transparency International and Saul Mullard, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre Date: 14 April 2020 The technical demands of setting up a secure and anonymous whistleblowing mechanism can seem daunting. Yet public sector organisations such as anti-corruption agencies do not need to develop their own system from scratch; there are a number of both open-source and proprietary providers of digital whistleblowing platforms that can be deployed by public agencies. This Helpdesk answer lays out the core principles and practical considerations for online reporting systems, as well as the chief digital threats they face and how various providers’ solutions respond to these threats. Overall, the paper has identified that open source solutions tend to offer the greatest security for whistleblowers themselves, while the propriety software on the market places greater emphasis on usability and integrated case management functionalities. Ultimately, organisations looking to adopt web-based whistleblowing systems should be mindful of the broader whistleblowing context, such as the legal protections for whistleblowers and the severity of physical and digital threats, as well as their own organisational capacity. U4 Anti-Corruption Helpdesk A free service for staff from U4 partner agencies Query Please provide an overview of the most common web-based whistleblower systems, exploring their respective advantages and disadvantages in terms of anonymity, security, accessibility, costs and so on. We are particularly interested in systems that would be appropriate for Anti-Corruption Agencies. Contents Main points 1. Background a. Advantages of digital reporting — Whistleblowing can act as a crucial systems check on human rights abuses, b.