Damien Broderick Terrible Angels the Singularity and Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

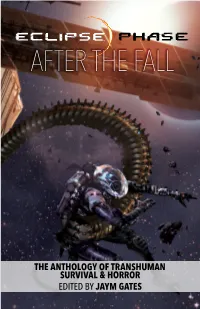

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Technological Singularity

TECHNOLOGICAL SINGULARITY BY VERNOR VINGE The original version of this article was presented at the VISION-21 Symposium sponsored by NASA Lewis Research Center and the Ohio Aerospace Institute, March 30-31, 1993. It appeared in the winter 1993 Whole Earth Review --Vernor Vinge Except for these annotations (and the correction of a few typographical errors), I have tried not to make any changes in this reprinting of the 1993 WER essay. --Vernor Vinge, January 2003 1. What Is The Singularity? The acceleration of technological progress has been the central feature of this century. We are on the edge of change comparable to the rise of human life on Earth. The precise cause of this change is the imminent creation by technology of entities with greater-than-human intelligence. Science may achieve this breakthrough by several means (and this is another reason for having confidence that the event will occur): * Computers that are awake and superhumanly intelligent may be developed. (To date, there has been much controversy as to whether we can create human equivalence in a machine. But if the answer is yes, then there is little doubt that more intelligent beings can be constructed shortly thereafter.) * Large computer networks (and their associated users) may wake up as superhumanly intelligent entities. * Computer/human interfaces may become so intimate that users may reasonably be considered superhumanly intelligent. * Biological science may provide means to improve natural human intellect. The first three possibilities depend on improvements in computer hardware. Actually, the fourth possibility also depends on improvements in computer hardware, although in an indirect way. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

SESSION: Archaeology of the Future (Time Keeps on Slipping…)

SESSION: Archaeology of the future (time keeps on slipping…) North American Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG) New York University May 22-24, 2015 Organizer: Karen Holmberg (NYU, Environmental Studies) Recent interest in deep time from historical perspectives is intellectually welcome (e.g., Guldi and Armitage, 2014), though the deep past has long been the remit of archaeology so is not novel in archaeological vantages. Rather, a major shift of interest in time scale for archaeology came from historical archaeology and its relatively recent focus and adamant refusal to be the handmaiden of history. Foci on the archaeology of ‘now’ (e.g., Harrison, 2010) further refreshed and expanded the temporal playing field for archaeological thought, challenging and extending the preeminence of the deep past as the sole focus of archaeological practice. If there is a novel or intellectually challenging time frame to consider in the early 21st century, it is that of the deep future (Schellenberg, 2014). Marilyn Strathern’s (1992: 190) statement in After Nature is accurate, certainly: ‘An epoch is experienced as a now that gathers perceptions of the past into itself. An epoch will thus always will be what I have called post-eventual, that is, on the brink of collapse.’ What change of tone comes from envisioning archaeology’s role and place in a very deep future? This session invites papers that imaginatively consider the movement of time, the movement of archaeological ideas, the movement of objects, the movement of data, or any other form of movement the author would like to consider in relation to a future that only a few years ago might have been seen as a realm of science and cyborgs (per Haraway, 1991) but is increasingly fraught with dystopic environmental anxiety regarding the advent of the Anthropocene (e.g., Scranton, 2013). -

A Deepness in the Sky Free

FREE A DEEPNESS IN THE SKY PDF Vernor Vinge | 560 pages | 14 Jul 2016 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781473211964 | English | London, United Kingdom A Deepness in the Sky - Wikipedia Audible Premium Plus. Cancel anytime. A Deepness in the Sky years have passed on Tines World, where Ravna Bergnsdot and a number of human children ended up after a disaster that nearly obliterated humankind throughout the galaxy. Ravna and the pack animals for which the planet is named have survived a war, and Ravna has saved more than one hundred children who were in cold-sleep aboard the vessel that brought them. While there is peace among the Tines, there are those among them - and among the humans - who seek power. And no matter the cost, these malcontents are determined to overturn the fledgling civilization By: Vernor Vinge. A Fire Upon the Deep is the big, breakout book that fulfills the promise of Vinge's career to date: a gripping tale of galactic war told on a cosmic scale. Thousands of years hence, many races inhabit a universe where a mind's potential is determined by its location in space, from superintelligent entities in the Transcend, to the limited minds of the Unthinking Depths, where only simple creatures and technology can function. Set A Deepness in the Sky few decades from now, Rainbows End is an epic adventure that encapsulates in a single extended family the challenges of the technological advances of A Deepness in the Sky first quarter of the 21st century. A Deepness in the Sky information revolution of the past 30 years blossoms into a web of conspiracies that could destroy Western civilization. -

THE MENTOR 81, January 1994

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #81 ARTICLES: 27 - 40,000 A.D. AND ALL THAT by Peter Brodie COLUMNISTS: 8 - "NEBULA" by Andrew Darlington 15 - RUSSIAN "FANTASTICA" Part 3 by Andrew Lubenski 31 - THE YANKEE PRIVATEER #18 by Buck Coulson 33 - IN DEPTH #8 by Bill Congreve DEPARTMENTS; 3 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 40 - THE R&R DEPT - Reader's letters 60 - CURRENT BOOK RELEASES by Ron Clarke FICTION: 4 - PANDORA'S BOX by Andrew Sullivan 13 - AIDE-MEMOIRE by Blair Hunt 23 - A NEW ORDER by Robert Frew Cover Illustration by Steve Carter. Internal Illos: Peggy Ranson p.12, 14, 22, 32, Brin Lantrey p.26 Jozept Szekeres p. 39 Kerrie Hanlon p. 1 Kurt Stone p. 40, 60 THE MENTOR 81, January 1994. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. Mail Address: PO Box K940, Haymarket, NSW 2000, Australia. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions, if over 5 pages, preferred to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD) in both ASCII and your word processor file or typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE anyway, for my comments. Contributions are not paid; however they receive a free copy of the issue their contribution is in, and any future issues containing comments on their contribution. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Selected Scifi 201102.Xlsx

Selected Used SciFi Books- Subject to availability - Call/email store to receive purchasing link ([email protected] 540206-2505) StorePri AuthorsLast Title EAN Publisher ce Cross-Currents: Storm Season, The Face of Chaos, Abbey, Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn B000GPXLOQ Nelson Doubleday,. $8.00 and Wings of Omen Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything 9780517548745 Harmony Books $8.00 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 9781127539635 BALLANTINE BOOKS $15.00 Adams, Douglas So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish 9780795326516 HARMONY BOOKS $6.00 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 9780517545355 Harmony $8.00 Adams, Richard MAIA 9780394528571 Knopf $8.00 Alan, Foster Dean Midworld B001975ZFI Ballentine $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Helliconia Summer (Helliconia Trilogy, Book Two) 9781111805173 Atheneum / $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Non-Stop B0057JRIV8 Carroll & Graf $10.00 Aldiss, Brian Wilson Helliconia Winter (Helliconia, 3) 9780689115417 Atheneum $7.00 Allen, Roger E. Isaac Asimov's Inferno 9780441000234 Ace Trade $6.00 Allen, Roger Macbride Isaac Asimov's Utopia 9781857982800 Orion Publishing Co $8.00 Allston, Aaron Enemy lines (Star wars, The new Jedi order) 9780739427774 Science Fiction $15.00 Anderson, Kevin J and Rebecca The Rise of the Shadow Academy 9781568652115 Guild America $15.00 Moesta Anderson, Kevin J,Herbert, Brian Hunters of Dune 9780765312921 Tor Books $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. A Forest of Stars: The Saga of Seven Suns Book 2 9780446528719 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber (Star Wars) 9780553099744 Spectra $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire: The Saga of Seven Suns - Book 1 9780446528627 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. -

Artificial Intelligence for Interstellar Travel

Artificial Intelligence for Interstellar Travel Andreas M. Hein1 and Stephen Baxter2 1Initiative for Interstellar Studies, Bone Mill, New Street, Charfield, GL12 8ES, United Kingdom 2c/o Christopher Schelling, Selectric Artists, 9 Union Square 123, Southbury, CT 06488, USA. November 20, 2018 Abstract The large distances involved in interstellar travel require a high degree of spacecraft autonomy, realized by artificial intelligence. The breadth of tasks artificial intelligence could perform on such spacecraft involves maintenance, data collection, designing and constructing an infrastructure using in-situ resources. Despite its importance, exist- ing publications on artificial intelligence and interstellar travel are limited to cursory descriptions where little detail is given about the nature of the artificial intelligence. This article explores the role of artificial intelligence for interstellar travel by compiling use cases, exploring capabilities, and proposing typologies, system and mission archi- tectures. Estimations for the required intelligence level for specific types of interstellar probes are given, along with potential system and mission architectures, covering those proposed in the literature but also presenting novel ones. Finally, a generic design for interstellar probes with an AI payload is proposed. Given current levels of increase in computational power, a spacecraft with a similar computational power as the human brain would have a mass from dozens to hundreds of tons in a 2050 { 2060 timeframe. Given that the advent of the first interstellar missions and artificial general intelligence are estimated to be by the mid-21st century, a more in-depth exploration of the re- lationship between the two should be attempted, focusing on neglected areas such as protecting the artificial intelligence payload from radiation in interstellar space and the role of artificial intelligence in self-replication. -

Jerks, Zombie Robots, and Other Philosophical Misadventures

Jerks, Zombie Robots, and Other Philosophical Misadventures Eric Schwitzgebel Schwitzgebel July 24, 2018 Splintered Mind, 1 Dear Reader, What follows are a few dozen blog posts and popular articles, on philosophy, psychology, culture, and technology, updated and revised, selected from eleven hundred I published between 2006 and 2018. Skip the ones you hate. Eric Schwitzgebel July 24, 2018 Splintered Mind, 2 Part One: Moral Psychology 1. A Theory of Jerks 2. Forgetting as an Unwitting Confession of Your Values 3. The Happy Coincidence Defense and The-Most-I-Can-Do Sweet Spot 4. Cheeseburger Ethics (or How Often Do Ethicists Call Their Mothers?) 5. On Not Seeking Pleasure Much 6. How Much Should You Care about How You Feel in Your Dreams? 7. Imagining Yourself in Another’s Shoes vs. Extending Your Love 8. Aiming for Moral Mediocrity 9. A Theory of Hypocrisy 10. On Not Distinguishing Too Finely Among Your Motivations 11. The Mush of Normativity 12. A Moral Dunning-Kruger Effect? 13. The Moral Compass and the Liberal Ideal in Moral Education Part Two: Technology 14. Should Your Driverless Car Kill You So Others May Live? 15. Cute AI and the ASIMO Problem 16. My Daughter’s Rented Eyes 17. Someday, Your Employer Will Technologically Control Your Moods 18. Cheerfully Suicidal AI Slaves 19. We Have Greater Moral Obligations to Robots Than to (Otherwise Similar) Humans 20. Our Moral Duties to Monsters 21. Our Possible Imminent Divinity 22. Skepticism, Godzilla, and the Artificial Computerized Many-Branching You 23. How to Accidentally Become a Zombie Robot Part Three: Culture 24.